Why Was Bleeding Kansas So Important?

In the decade before the American Civil War, Kansas bled. "Bleeding Kansas" was a preview of the bloody war to come, per Britannica, when pro-slavery and antislavery Americans rushed to settle Kansas — and inevitably engage in conflict with the other side.

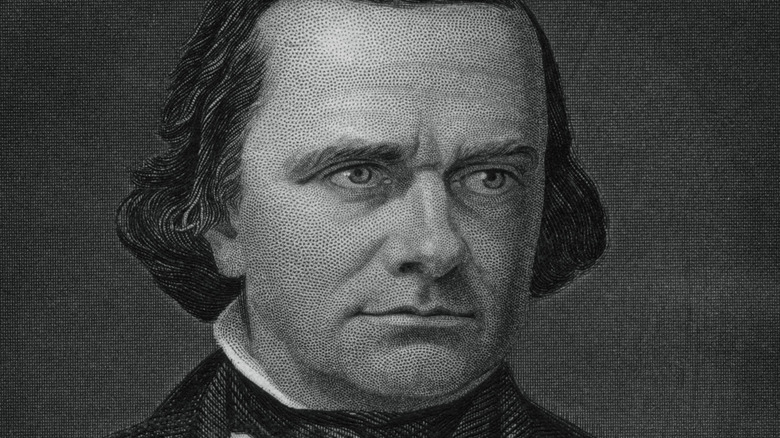

When the new Kansas territory was staked, there was a question of whether it would allow slavery or, like much of the north, outlaw it. As a compromise, the Democrat Stephen A. Douglas passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which essentially said that Kansas' status as a free or slave state would be determined by its future settlers under the principle of popular sovereignty (via Britannica).

What ended up happening, however, is that neither side was happy with the compromise. On the more moderate end, the antislavery Republican Party was founded as a political response to the question of abolition. But in the state of Kansas itself, a Civil War in miniature broke out.

The prelude to Civil War

Northerners began funding settlers to move to Kansas and vote in their local elections, according to History, while many Southerners who settled in nearby Missouri traveled to Kansas in order to vote illegally. The Southern approach initially won out, and early politicians from the state backed pro-slavery causes. Abolitionists, however, refused to recognize this government and elected their own, along with building up a militia to defend themselves from expected future clashes.

They didn't have to wait long. Bleeding Kansas began in earnest with the 1856 Sack of Lawrence, in which pro-slavery advocates burned down a hotel and newspaper office in the Kansas town of Lawrence because they felt the paper was unduly abolitionist (per Britannica). In response to the attack, the radical Republican Charles Sumner, a senator from Massachusetts, gave an address condemning the violence in Kansas, and was promptly beaten within an inch of his life by a pro-slavery politician — Congressman Preston S. Brooks of South Carolina.

The Sack of Lawrence infuriated the anti-slavery radical John Brown, who gathered a band of men, including his own sons, and began attacking and killing pro-slavery settlers. Brown would later be hanged after he attempted to lead a slave uprising at the armory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia (via Britannica).

Violence waned after 1856, but continued to some degree until Kansas was admitted as a free state in 1861 — after the South had seceded, and three months before the Civil War began.