The Truth About The Man Who Commissioned A Park Of Monsters

Wander through the Italian town of Bomarzo and you might soon lose yourself in a forest inhabited by fantastical creatures forever frozen in stone. They could be gods. They could be monsters. It all depends on how you see them, and centuries after they came to life, nobody really knows what the sculptures commissioned by Duke Pier Francesco "Vicino" Orsini are trying to say. Not even the gaping "mouth of hell" speaks.

Born in 1523, Orsini was a cultured man, a patron of the arts who is thought to have suffered from trauma after being held as a prisoner of war and being faced with his first wife's untimely death, as The Vintage News details. The "Parco dei Mostri" (Park of Monsters) he commissioned was unlike anything the Renaissance had ever seen. It was not orderly or conventionally beautiful in terms of the ideals of the period but a discordant and unsettling place that questioned reality. It was also a mashup of aesthetics. Orsini had his artist, Pirro Ligorio, create sculptures inspired by everything from ancient Etruscan art to twisted versions of mythological figures.

Take a virtual walk through this garden of horrors — or is it marvels — and decide for yourself what they could have emerged from.

His monstrous garden was anti-Renaissance

The Renaissance saw a revival of classical art and architecture — but Vicino Orsini wanted to go against all that. As Slate says, he turned the Renaissance garden aesthetic, which emphasized beauty, elegance and proportion, inside out with a menagerie of curious beasts. Its scattered layout seems to make no sense and is the opposite of harmony.

The sculptures in the Parco dei Mostri exaggerate proportions and menacingly come at you from tangles of branches and shrubs instead of rising out of perfectly manicured greenery. If this seems accidental, Orsini wanted the place to be overgrown, according to BBC Travel. He purposely allowed the surrounding growth to go wild around his stone monsters. What defined Renaissance art was dismantled by this haven for the bizarre. World History Encyclopedia describes the artistic works of the period as a resurrection of antiquity combined with logical thought and realism, intended to provoke emotion through subtle meaning.

There is no shortage of details or hidden meanings in the Park of Monsters. However, during an era when everything was supposed to fit in with ancient Greek and Roman ideals of beauty, the sculptures that emerged from Orsini and Pirro Ligorio's imaginations could have been a shock to any who meandered into the Sacro Bosco and encountered something like the gaping mouth of Orcus or "mouth of hell" (pictured at top), which is the unofficial poster child for this garden.

He was a real Epicurean

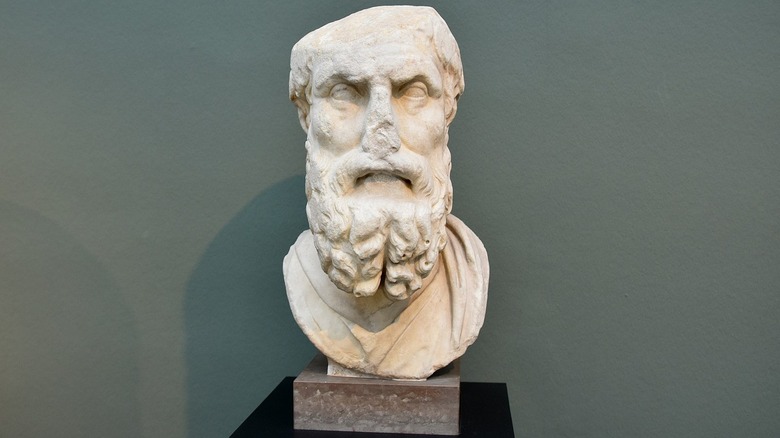

Epicurean is often associated with food now, but according to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Epicureanism had started centuries earlier with the philosopher Epicurus. He emphasized that happiness meant banishing pain and fear and reveling in the tangible world, because he didn't think there was any sort of existence beyond death. You needed to seize a pleasurable life while you could.

The Stanford Encyclopedia states Epicurious was adamant that he could prove death was actually the end, and people didn't have to fear enternal torment of the soul. Epicureanism wanted nothing to do with religion. Its founder believed that deities wanted nothing to do with mortals, so there was really no point in reaching out to them. He was also dubious about sex and marriage and politics. Vicino Orsini had practiced formalized religion but, as The Vintage News says, eventually converted to this belief system as a form of therapy after he was released from being a prisoner of war.

This it seems unexpected for him to hire the pope's former architect to design something that the pontiff himself probably wouldn't have approved of. Pirro Ligorio had been behind some of the stunning architecture for papal architecture, according to the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences, and other wealthy patrons.

Myths and legends were some of his inspirations

Even though they are the nightmarish opposite of classical ideals, the sculptures in the Gardens of Bomarzo are thought to have been inspired by mythological figures of Greco-Roman mythology, according to Ancient Origins.

There seems to be more irony in this inspiration and execution (which turns Renaissance art on its head). In an article published in Garden History, historian Lynette Bosch states that confirms that fact, noting garden's symbolic roots in classical mythology. You might recognize the winged horse Pegasus or the three-headed canine guardian of the underworld, Cerberus, in their more unsettling forms, along with uutsize mermaids thought to be Sirens, as per Ancient Origins.

As Annette Taylor notes in her study "The Sculptural Allegories Hidden Within the 'Third Nature' of the Gardens of Bomarzo," the sculptures were inspired by the works of luminaries such as Dante, Petrarch, and Ariosto, among others. It might have had something to do with Vicino Orsini being one of the literati, among whom Taylor says were "intellectuals, humanists, and aristocrats whom would be well-versed and informed on many of the allegories" behind the beasts. Even unconventional Renaissance gardens were supposed to make you think.

Another inspiration was Etruscan art

As historian John P. Oleson notes in the Art Bulletin, there have been Etruscan tombs unearthed near the town of Bomarzo, and it is thought that at least some of the sculptures in Vicino Orsini's garden is meant to emulate such a funerary monument. There are aspects of the garden that echo the ancient civilization that thrived in Italy long before the Roman Empire.

In his study Oleson solidifies this connection, identifying the garden as an Etruscan necropolis full of winged and snake-like monsters that recall those on ancient funerary urns and other carvings and creatures that he thought recalled Etruscan demons, grave goods, even jewelry. The problem is that there is no known tomb or other work of art that any of these were directly inspired by — they just take on the aesthetic.

Orsini was into antiquities, and so was Pirro Ligorio, who was an actual antiquarian, according to historian a study in the Papers of the British School at Rome. That might explain why both were so drawn to the motifs, deities, and demons of a vanished people. The Etruscans were inspired by the ancient Greeks, according to Ancient Origins. Remember that ancient Greece heavily influenced the art of the Renaissance. An Etruscan version of Medusa does look as if she is related to Orsini's Orcus, but whether or not she was the inspiration for the "mouth of hell" is forever a mystery.

Vicino Orsini's designer was also into the grotesque

Pirro Ligorio, the artist and architect Vicino Orisini commissioned, was also fascinated by the grotesque. As historian John A. Gere says in his study in Master Drawings, some of the drawings of the formal papal architect show things such as "monstrous hands, clumsily attached to the arms by grotesquely malformed wrists" and other exaggerations that turn classicism on its head. This style would later go into Orsini's monsters.

Not all of Ligorio's work is nightmare fuel. Long before he would design the Parco dei Mostri, he drew and painted scenes that were visions of classical beauty. His interpretation of an ancient oracle, which was auctioned by Christie's, has that proportional idealism reflective of Renaissance art and architecture, obvious in its human figures and even the few pieces of furniture around them. This was nothing like caricatures that appeared in his later work.

According to a study published in the Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Insitutes, Ligorio had ideas of what monstrous mythical creatures such as sirens, giants and dragons should look like. He was annoyed at the discrepancy in how the ancients described them and the ways that Renaissance artists ended up rendering them. He felt that his contemporaries made them too human, and that they should have been much more grossly exaggerated.

Monsters were embodiments of Mannerism

Mannerist artists created works that went against nature, with all sorts of twists on reality — and they are supposed to make you feel uneasy. The National Gallery of Art says that Mannerism was defined by an artificial aesthetic instead of realism. You can see this in all the exaggerated features and proportions of the monster sculptures that lurk in the Sacro Bosco.

Some Mannerist works of art almost appeared realistic at first, but they were the sort of thing that would make you do a double take before you realized there was nothing real about them. They were the stark opposite of everything classicism stood for (and therefore what was expected of Renaissance art). Though it is an obvious rebellion against classical beauty and symmetry, Mannerism supposedly arose out of political upheaval and the sudden outburst of the bubonic plague.

Vicino Orsini's creatures were, according to Slate, inspired by sources as disparate as ancient myth and modern religion. These might have not been his only muses. Michaelangelo was the unexpected inspiration behind the monsters in the garden, if you ask art historian Enrico Guidoni, who told Italy Magazine that they "show Michelangelo's imagination had a playful side, giving Mannerism a jolt of the surreal."

They are also thought to be visuals for his trauma, especially the elephant

The haunting sculptures in the Gardens of Bomarzo are often thought to be visuals of Vicino Orsini's grief. He suffered intense trauma during his life, and the massive elephant statue "Elefante" that appears to trample through his tangled garden came out of memories from his military career that haunted him. While fighting in the Battle of Hesdin, he saw his friend Orazio Farnese killed and was himself seized as a prisoner of war, according to Lynnette Bosch in Garden History.

Bosch says that "Vicino's autobiographical references are discernible in Bomzarzo's 'Elefante,'" going on to explain that the symbolism of the animal carrying a corpse in his trunk relates to the death of Farnese, while his own imprisonment is represented by the tower on its back. There is also imagery that suggests a link between the threat of opposing forces.

Something else that Bosch noticed to be a possible sign of the elephant embodying Orsini's traumatic experience at Hesdin is Giovanni Guerra's drawing of the statue, which shows the saddle on the elephant's back abloom in "Orsini roses." It makes you think.

The giant was supposedly born of an affair

"Gigante" the giant was one of the last monsters built, and while thought to be inspired by Lodovico Ariosto's epic poem "Orlando Furiosio," it had chilling parallels to Vicino Orsini's own life. "Orlando Furioso" is a love story turned bitter. According to Columbia University, the poem follows the downward spiral of scorned knight Orlando after he finds out that his love interest Angelica has lost her virginity to a foot soldier ranking far below him. Orlando then literally tore his adversary apart in an outburst of jealous rage.

Like "Elefante" which came before it, "Gigante" was drawn by Giovanni Guerra, as Garden History reveals, and Guerra wrote the identities of the killer and the victim (which were previously unclear) on the drawing. Orsini had been married during his time in the military and as a prisoner of war. However, his first wife died soon after, and he was horrified to find out his mistress had run off with another man. This is potentially what drove him to commission "Gigante" as another embodiment of wrenching pain.

That mouth was actually meant to eat in (if you dare)

There is a creepy duality about Orcus, whose infamously gaping mouth is also a space meant for people to sit and eat (complete with a table), as per Atlas Obscura. It's as if you're eating and getting eaten at the same time.

Art historian Luke Morgan told the Sydney Morning Herald that he saw this sculpture as a vision of dark humor that also provoked fear. His opinion came out of wondering "What ... a Renaissance person would have thought as they encountered it and what kind of cultural experience and knowledge they would have brought to motifs like this." Morgan also sees this sculpture as the ultimate visualization of devouring, as historian Guy Tal discusses in Sixteenth Century Journal. It might even evoke cannibalism. What Morgan also sees as giving this sculpture its monster-like quality, according to Tal, is that Orcus is a massive disembodied head.

Another inspiration for the mouth that looks like it could swallow a human alive is apparently Dante's "Inferno," as The Courtauld Institute of Art notes, because the ominous inscription over the mouth tells anyone entering to abandon all reason. Dante tells anyone crossing over into hell to abandon all hope.

Whether the garden was in memory of his wife is shrouded in mystery

It is unknown whether the temple Vicino Orsini had built in the garden, and really the entire garden, was supposed to be a memorial for his first wife, Giulia Farnese. She was related to the commander Orazio Farnese who Orsini fought beside and mourned.

Atlas Obscura says Orsini created what he called a "Villa of Wonders" in the wake of her death. Nobody knows exactly when she died. In her study in Garden History, Lynette Bosch tries to figure out how long she lived after Orsini was released from captivity as a prisoner of war, and his wife was supposedly still alive at the time, or at least is mentioned as alive in a 1556 publication from one of Orsini's contemporaries. The monsters first started to appear in 1552.

Later, as Bosch says, a letter to Orsini in 1564 refers to "'teatri e mausolei' at Bomarzo," which translates to "theaters and mausoleums," so it is understandable why she believes that this could be a reference to a memorial sculpture. There were other letters to and from Orsini that also suggested the temple was built in her memory. A supposed mortuary temple is a temple that is perched at the highest point in the Sacro Bosco, and Bosch thinks that "its funerary function extends, by association, to the garden's structure."

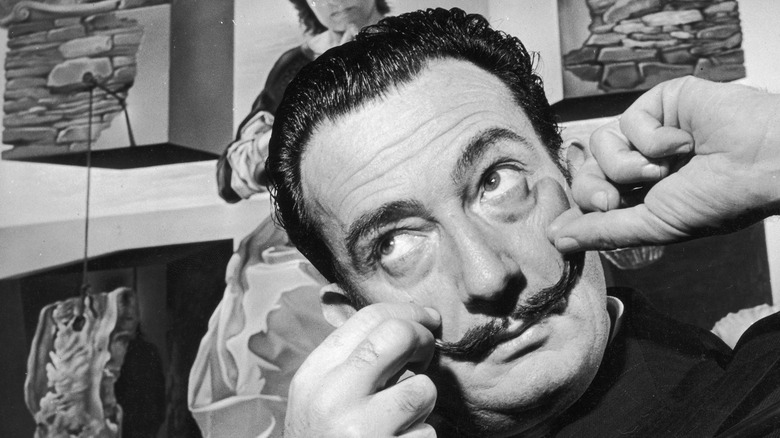

Salvador Dalí was inspired by the garden

After the death of Vicino Orsini, the garden became wildly overgrown and almost lost to memory until it was discovered by Surrealist painter and filmmaker Salvador Dalí in 1938. Surrealism, as defined by the Tate Gallery, juxtaposes reality with what is hidden in the shadows of the unconscious. Dalí was so inspired by Orsini's monstrous visions that his painting, "The Temptation of Saint Anthony," which is also one of his most famous, heavily draws on inspiration from the Parco dei Mostri, according to Atlas Obscura.

Looking closely at the painting, the elephants carrying towers are hauntingly reminiscent of "Elefante" in Orsini's garden, even if none are carrying a limp corpse. Dalí also felt compelled to shoot a short film about the bizarre stone creatures that inhabited the forsaken place. As Thalia Allington-Wood in Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes, the artist "marked the emergence of a lasting frame of reference for the interpretation of the Sacro Bosco."

Dalí's film, "In the World of the Surreal: Salvador Dalí in the Garden of Monsters," aired on November 10, 1948. It was one of the first films that revealed this marvel onscreen. Allington-Wood reports that he climbed the sculptures as an orchestra record played in the background.

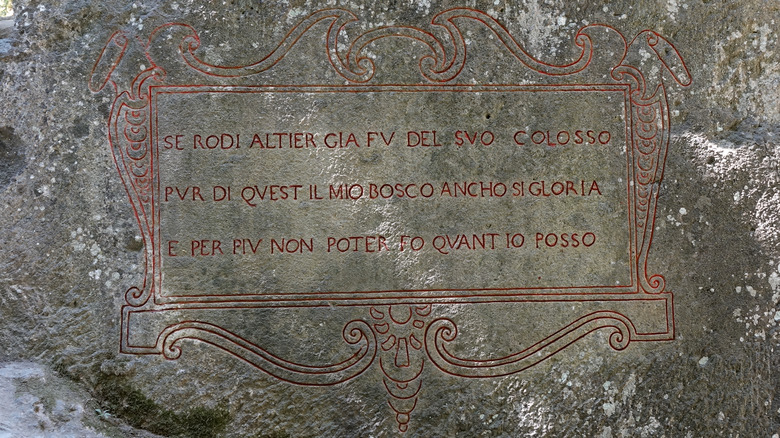

He left cryptic inscriptions behind

Though Vicino Orsini would never confess why he commissioned the Garden of Monsters, an inscription in the stone, translated by Italian Sons and Daughters of America (ISDA), states, "Thou, who enter this garden, be very attentive and tell me then if these marvels have been created to deceive visitors, or for the sake of art." What does this even mean? Whoever comes up close to these immortal creatures can decide.

Every generation has left behind its own interpretation of the garden, as Anatole Tchikine says in an article published in Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes. He himself sees it as a celebrated but misunderstood landmark. It was glimpsed but often forgotten until Salvador Dalí, poet Jean Cocteau, and others gave the anti-Renaissance garden its own renaissance. Another peculiar inscription that ISDA highlights is "just to set the heart free." Is that the reason these monsters came into being, and what even did it free Orisini's heart of?

The interpretations of others are what Tchikine believes create their own myth about this "Renaissance Disneyland" and obscure the actual meaning of the sculptures, whatever that really is. Whether Orsini would approve of how it was seen through the centuries can only be left the imagination.