The Unsolved Murder Of Union Activist Pete Panto

The death of the man who inspired the main character of the gritty film "On the Waterfront," brilliantly directed by Elia Kazan, is still unsolved today. Much like union leader Jimmy Hoffa's demise, Pete Panto's killing has gone down in American history for highlighting organized labor's dark, disturbing past, linked to violence.

As The New York Times detals, Panto is believed to have been killed by the mob for agitating against the leadership of the International Longshoremen's Association, which at that time was under the thumb of organized crime. Back when the men unloading the bustling docks in America's largest coastal cities labored in brutal, dangerous conditions, Panto's death sounded another hopeless note for the workers who toiled long hours unloading cargo, only to face corruption in the organizations that should have protected them -– and it went all the way to the top.

Like the character played by Marlon Brando in the acclaimed film loosely patterned on his life, Panto "could have been a contender" — not in boxing, but in cleaning up the leadership of the huge and powerful union. Tragically, it was not to be.

Pete Panto was born in Brooklyn but grew up in Messina, Sicily

Although he was born in New York, Pete Panto's mother later died giving birth in 1912, when he was around 2 years old, and he was sent abroad to be raised by relatives in Sicily, according to The New York Times. At that time, southern Italy was still basically run as a feudal system, with a man's daily wages controlled by a lord-like "padrone" whom –- he hoped -– would choose him out of a crowd of workers who assembled every day. Kickbacks assuring he would be chosen were also part of the system, in which laborers were treated much as serfs were in medieval times. Perhaps despairing of these conditions, Panto returned to the United States in 1934 and began working at the docks lining the shores of the borough where he had been born.

He was very unlike the character who played him in the landmark film "On the Waterfront," however. Far from a punch-drunk, washed-up fighter, Panto was a charismatic speaker who enlisted his fellow workers in the fight against the corruption he soon discovered at the docks, according to Nathan Ward in his book "Dark Harbor: The War for the Brooklyn Docks." Calling for regular union meetings, Panto encouraged his fellow stevedores, declaring, "We are strong. All we have to do is stand up and fight."

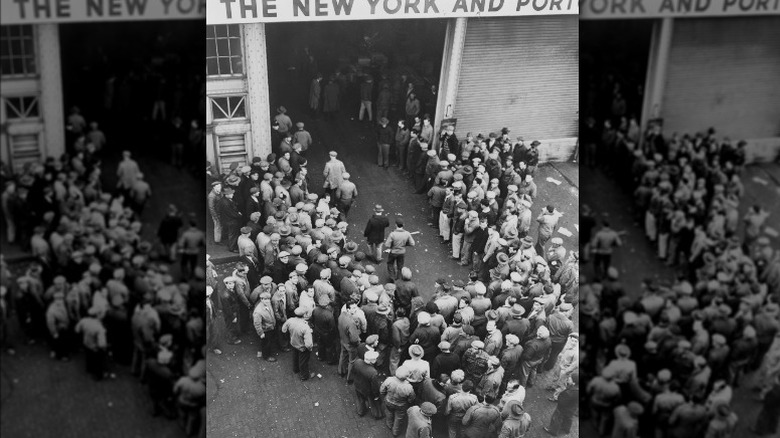

Dockworkers in New York had to line up to ask for jobs

Incredibly, when Pete Panto returned to New York in 1934, he found that men who hoped to find work unloading cargo along the New York City waterfront were forced to, in effect, beg for it, much like in the feudal system that still reigned in the Mediterranean. This was universally known in the largest ports of the U.S. as the daily "shape up," The New York Times reports. Upon seeing the men as they lined up in the mornings along the docks in Red Hook in Brooklyn, American playwright Arthur Miller once declared, "America stopped at Columbia Street."

The stevedores who unloaded the millions of tons of cargo not only had to basically act as supplicants for jobs, they had to offer kickbacks to their union, the International Longshoremen's Association, as well -– and if the men didn't work for a few days, bailiffs would follow up on them to see what was happening, the Guardian notes.

Miller also famously said of the Brooklyn docks that they were "a dangerous and mysterious world at the water's edge that drama and literature had never touched."

The mob really ran the union

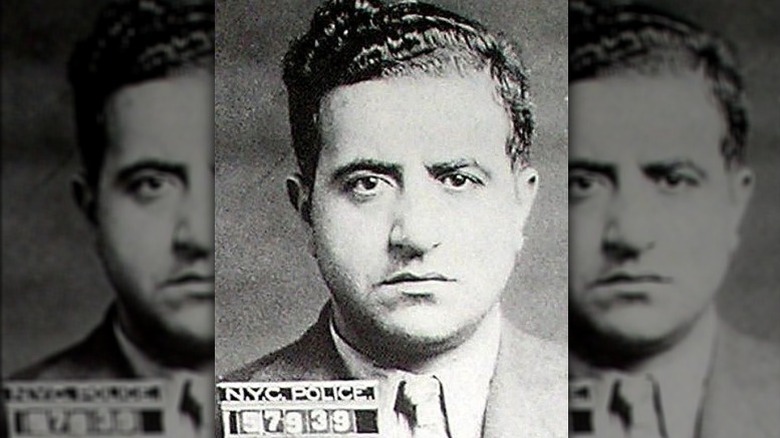

The New York mob was quick to hone in on the huge profits that could be made from the dues that desperate longshoremen paid in a misplaced effort to obtain better working conditions and the kickbacks that they were expected to pay to even be considered for work. As told by Robert Niemi in his book, "History in the Media," although the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA) was headed by the feared Joseph Ryan, the union that controlled the waterfront was notorious for its association with the mob — particularly Albert Anastasia, Ryan's right-hand man and the head of the Mafia hit-man squad known as "Murder, Inc.," iitaly notes.

Anastasia had been charged with killing a man with an ice pick in 1932, two years before Panto started work as a stevedore; the FBI recorded that the case was dropped due to lack of evidence. As iitaly notes, the ILA had as its vice president none other than Emil Camarda, an associate of Anastasia whose brother, known as "Tough Tony"Anastasia, also did his bidding.

With the rot going all the way to the top of the ILA, Niemi calls Ryan — although not technically a member of the mob himself — an extremely corrupt leader who considered himself to be life-long president of the union.

Pete Panto became hiring foreman in 1939, immediately agitating for labor reform

Longshoremen at the great port of San Francisco had won meaningful job improvements after a 1934 strike, including the abolishment of the shape up system, which had originally been imposed by the shipowners there, as noted by People's World (formerly the Daily Worker). New York City, however, lagged behind in establishing workers' rights -– and in cleaning up the powerful, completely corrupt unions that controlled the waterfront.

In 1939, just five years after Pete Panto returned to the U.S. to start work as a longshoreman on the Brooklyn docks, he assumed the powerful position of hiring foreman, The New York Times records. Fearlessly, he immediately began to speak out against the unfair hiring practices there, attracting support from 2,000 of the longshoremen of the city. He must have known what he was up against, however, since the ILA was notorious for its association with the mob.

He disappeared after refusing a mob bribe

As told in the book, "Dark Harbor: The War for the Brooklyn Waterfront," Pete Panto was warned by mob boss Albert Anastasia's associate Emil Camarda – the ruler of the local Brooklyn union shops — that he must stop his efforts to reform how men were chosen for work on the docks. Camarda threatened Panto, saying that "some of the boys" were unhappy with his actions getting the dock workers riled up. "The boys" was a universally understood code that constituted a dire warning for anyone who dared to cross the ILA. Camarda also offered Panto a bribe to stop agitating for union reform. The money came to the then-princely sum of $10,000, The New York Times states. Sadly, Panto's fate had been sealed after he formed the Brooklyn Rank and File Committee after the warning, the Tablet says.

Shortly afterward, on July 14, 1939, Panto was last seen getting into a sedan with Camarda. He had told his fiancee's brother to call the police if he wasn't back by 10:00 a.m. the next day, notes iitaly. He was taken to a house where Anastasia and enforcer Mendy Weiss met him, according to Abe Reles, a hitman who turned informant, speaking to the Brooklyn district attorney. It was there that Weiss killed Panto.

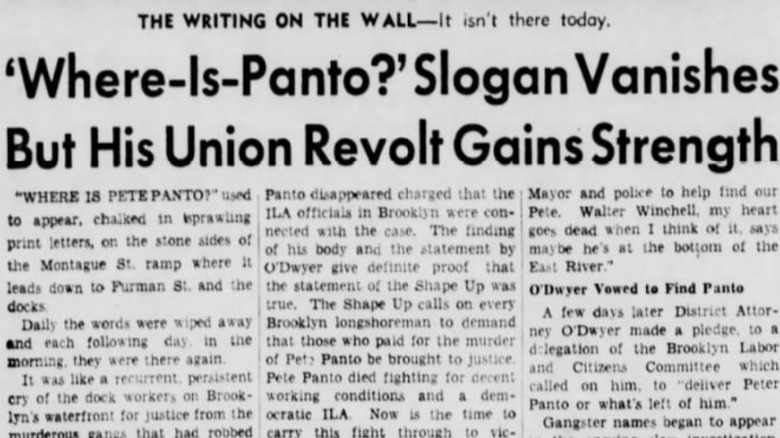

HIs coworkers wrote his name on overpasses to keep his memory alive

As historian William Mello noted in "New York Longshoremen: Class and Power on the Docks," Pete Panto's merit-based hiring system called the Rank and File Committee, which he formed after he refused the union's bribe of $10,000, survived him; however, according to Nathan Ward's book, "Dark Harbor," Panto had been replaced with a more ILA-friendly hiring boss, and dock workers were back to being afraid and submissive.

Knowing the system was gamed against them, Panto's fellow dockworkers kept his memory alive the only way they felt they could — by writing the question "Dov'è Pete Panto?" ("Where is Pete Panto?") in graffiti, chalked on overpasses, sidewalks, and wherever they managed to do so without being caught, reported the Brooklyn Daily Eagle at the time. The message was erased every day but re-chalked every night. Sometimes in English and at other times in Italian, notes The New York Times notes. the graffiti was a plaintive cry at a time when dockworkers justifiably feared for their lives if they dared to go against the incorrigibly corrupt ILA.

But it was being noticed — even by such prominent writers as the renowned syndicated columnist Walter Winchell, who wrote about seeing the graffiti. As recorded in "Dark Harbor," Winchell stated in one of his stories: "Police fear Pete is wearing a cement suit at the bottom of the East River."

His body was found in a lime quarry in New Jersey

After Pete Panto's disappearance, Brooklyn District Attorney William O'Dwyer ordered a search of likely mob victim burial sites, as per The New York Times. In 1941, 18 months later, his body was finally unearthed in a pit in Lyndhurst, New Jersey. As Robert Niemi states in "History in the Media," the area was common location for the mob to bury their bodies.

The New York Times reports that O'Dwyer even knew the identity of the labor organizer's killers. As the Tablet relates, hitman-turned-informant Abe Reles told authorities that it was none other than Murder Inc.'s Albert Anastasia who had ordered Panto's death. Predictably, Reles was soon found dead on the sidewalk under the window of the room where he had been guarded by no less than six policemen.

The Tablet says that John Heyer, whose family operated the funeral home which took care of Panto's body after it was discovered, stated the labor organizer had been not only been stabbed in the chest but strangled as well. According to The New York Times, no one was arrested for his murder, and the truth of the outspoken advocate for dock workers was nearly forgotten.

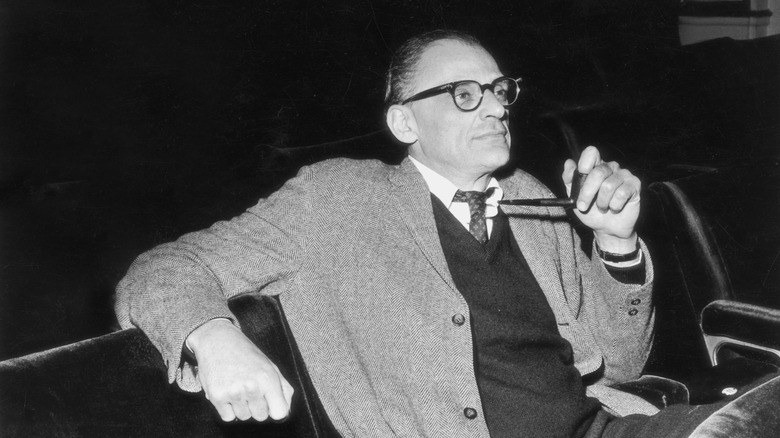

Arthur Miller wrote a screenplay after seeing 'Where is Pete Panto?' graffiti

When acclaimed American playwright Arthur Miller spied graffiti asking "Dov'è Pete Panto" ("Where is Pete Panto?") one day in the late 1940s while walking through Brooklyn, he was inspired write a screenplay called "The Hook," patterned on Pete Panto's life and death, according to Robert Niemi in "History in the Media." He was intrigued by the underworld of the docks he subsequently uncovered.

Alongside his friend, director Elia Kazan, Miller pitched it to Hollywood but withdrew it after the FBI — to which studio exec Harry Cohn had given the script — insisted that Miller paint the unions as communist in an effort to make the context more political (this was after all during the beginning of the Cold War and the machinations of the House Un-American Activities Committee, as per History). Miller refused and the project was shelved until Kazan tweaked the idea. The resulting film, "On the Waterfront," became a seminal moment in film history, documenting the ugly reality of life on the docks — and winning eight Oscars, per The Washington Post.

Incredibly, despite the great acclaim for Miller as America's most prominent playwright of the time, "The Hook" was not staged until 2015, one hundred years after his birth, the Guardian reports. However Miller did publish "The View from the Bridge," a reworking of his original screenplay.

Broadcast by the BBC Radio 4, director James Dacre told the Guardian that he had been intrigued by the parallels to today's labor issues, including the zero-hours contracts under which many people even today are employed. He noted that "Miller can't seem to write a line without finding the humanity of that character. ... Everybody's balanced between what they do right and wrong, between the collective good and their individual good."

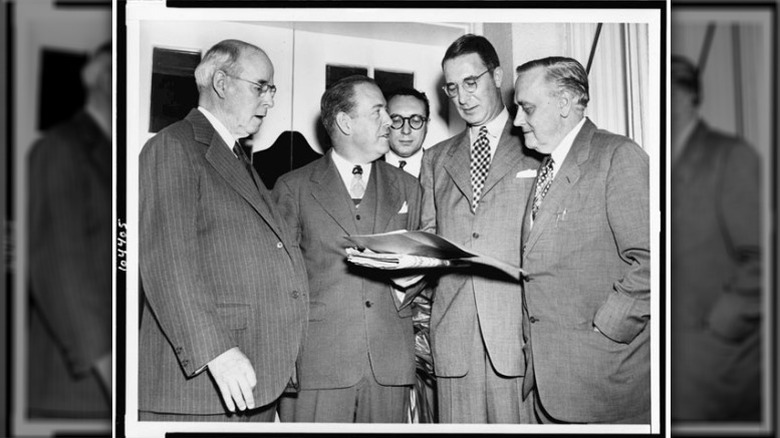

His murder led to televised congressional hearings

The death of Pete Panto -– along with many other victims who had spoken up against the corruption of the Brooklyn docks — finally led to the systematic cleanup of the union and the way the docks were managed. Spurred by a courageous series of stories written by journalist Malcolm "Mike" Johnson in 1948, the endemic corruption of the waterfront was finally laid out before an aghast American public. The series, which won him a Pulitzer Prize in 1948, resulted in the groundbreaking congressional hearings, called by Sen. Estes Kefauver in 1950, as per "Dark Harbor: The Fight for the Brooklyn Waterfront," Nathan Ward.

These televised hearings, which at one point drew an audience of no less than 30 million Americans, according to the U.S. Senate, finally forced the gangsters who had run the waterfront so brutally for so many years to appear before the authorities, bringing them to heel after decades of their reign of terror. By March of 1951, an astounding 72% of Americans stated they were aware of what was happening with the Kefauver hearings. LIFE magazine stated at the time that the investigation had become a national dialogue. The mob would never again rule the New York City docks with the complete impunity it had for years.

His body was buried in an unmarked grave in St. Charles Cemetery

Incredibly, Pete Panto was buried without even the dignity of a grave stone, perhaps because authorities wanted to avoid it becoming a place of pilgrimage for his supporters — or because they didn't want the mob to destroy the grave, La Voce di New York hints. That part of the story appears to be lost to history.

The Tablet states Panto's gravesite was only found by Joseph Sciorra, who heads up the Calandra Institute in New York City, after he combed the records of St. Charles Cemetery in Farmingdale. Aware of Panto's tragic story, Sciorra took it upon himself to arrange for a stone on which Panto's name could finally be engraved. "Not only was he erased from the historical record, but here he is erased again in the cemetery," said Sciorra to The New York Times. "It was heartbreaking."

Even Anthony Camarda — a distant relative of the man witnesses said was involved in his disappearance — praised Panto, bemoaning the fact that his memory had been almost forgotten. "This guy changed the whole industry, and there's nothing to remember him by," Camarda said.

As of 2022, a fundraiser has been launched to pay for and erect the gravestone. When the stone is placed, the epitaph will include part of this poem, written anonymously on Panto's death: "Drop hooks all you longshoremen/ This Panto burial day/ This working man from off the docks/ Our martyr in the fray."