Surprising Things That Happen After The United States Declares War

War is hell, the saying goes, and it's tough to imagine the feeling of dread that gripped the nation as they listened to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt utter those now-famous words for the first time: "Yesterday — December 7, 1941 — a date which will live in infamy — the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by the naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan." The attack, it turned out, had been years in the planning — and with it, the gloves came off, and the U.S. waded into a war that had been already drenching the world with blood.

No one wants to think of the nation going to war, not again. But it does bring up an interesting question: What happens when those documents are signed, that switch is flipped, and the point of no return is crossed?

There's a lot of highly visible stuff: We all imagine that troops are mobilized, more are put on high alert, security might double down at the borders ... that sort of thing. But do some digging into what laws and procedures are triggered by war deep behind the scenes, and there's some pretty surprising stuff that happens. Like what? Like this.

It kick-starts the construction of military projects

The Congressional Research Service has taken an in-depth look at everything that happens when the nation declares war, and it's wildly complicated. They confirm that there's a lot of legislation that gets activated in the moments that war is declared, and that includes specifying the directives issued to the military. But that doesn't mean just in terms of fighting, as there are statutes that also talk about the directives issued to the military's engineers and builders.

One part of the legislation talks about the power of the Secretary of Defense, in regards to building projects. It essentially lets them give orders to spend money on critical infrastructure without needing to go through Congress for approval. Need to build roads? Bridges? Railways? As long as it's in support of the military, go for it. There's even an addition to that, which allows for the construction of projects "not otherwise authorized by law," if deemed necessary for military support.

At the same time, though, that also means that any domestic projects that the Army's civil team is working on can immediately be put on hold. The Army's doing crucial repairs to that dam? That'll just have to wait.

Statutes of limitations are put on hold

The U.S. legal system is incredibly complicated, and one of the things that gets talked about a lot in police procedurals and criminal law dramas is the statute of limitations. That's essentially how long the courts have to bring charges against someone, and that period of time varies. In the case of things like destruction of government property and aircraft-related crimes, those have a statute of limitations of eight years. It's 10 for financial crimes like racketeering, and if the death penalty's on the table, there's no limit.

Interestingly, the Congressional Research Service says that when the nation declares war, the clock stops ticking on those statutes of limitations. In a nutshell, when the dust settles and someone's brought to court over, say, terrorist activity or the use of weapons of mass destruction, the time that the country was at war gets taken off the time applied to the statute of limitations. And that can mean a difference of years.

Arrests and removals of alien enemies

One of the most controversial parts of the U.S. involvement in World War II was the internment camps. Starting in 1942 and lasting for several years, around 125,000 people — including many children, and many American citizens — were forced from their homes and moved to internment camps, simply because they had Japanese ancestry. Camps were spartan, life was pretty miserable, and armed guards were everywhere. In the 1980s, the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians looked into the events that unfolded under Executive Order 9066, determined that they hadn't been necessary, and that led to both an apology and reparations that started to be paid out in 1990.

That's pretty shocking stuff, but perhaps more shocking is that according to the Congressional Research Service, it's entirely possible for the same thing to happen again. There are still laws in place, namely the Alien Enemy Act (via the U.S. House of Representatives), which authorizes the president to "apprehend, restrain, secure, and remove alien enemies ... whenever there is a declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government."

The laws apply to anyone over the age of 14, and they're pretty vaguely worded. In a nutshell, it's up to the president to determine how non-naturalized residents are dealt with, including: "the manner and degree of the restraint to which they shall be subject [to]."

Laws restricting chemical and biological weapons are suspended

There are a ton of rules and regulations put in place around the development and use of chemical and biological weapons. After World War I, the International Committee of the Red Cross called them "barbarous inventions," and the establishment of the Geneva Convention rules outlawed their use and made the repercussions of using them very clear.

There are also a ton of laws on the books governing the U.S.'s research and production of chemical and biological weapons (via GovRegs), including one that pretty much says, "Don't do it." The laws cover things like the movement and disposal of said weapons and lethal substances, and put a hold on the research and development of new weapons. Except, as it turns out, they're all overturned with a declaration of war.

The statute reads (in part): "After November 19, 1969, the operation of this chapter [devoted to restrictions on chemical and biological weapons] or any portion thereof, may be suspended by the President during the period of any war declared by Congress..."

FISA gets suspended

The idea that federal authorities can spy on U.S. citizens has always been wildly controversial, and things really came to a head after Watergate. That's when The New York Times revealed the fact that the CIA had — for a long time — been carrying out a secret, intelligence-gathering program that targeted Americans. What unfolded was a scandalous series of revelations, which included the fact that the government agencies had been actively spying on those believed to be members of the Communist Party, supporters of radical groups like the Black Panthers, and some of the most vocal opponents of the Vietnam War.

The result was the establishment of the Foreign Service Intelligence Act (FISA), which put in place a governing body that would hear requests for surveillance orders, then approve or deny those orders. The details of how the system operates have been amended and changed over the years, but the gist remains the same.

During a declaration of war, however, things change in a big way. FISA includes a provision that says that when war is declared, the president can essentially ignore the need to go through the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, and give the approval for surveillance themself. According to the Congressional Research Service, the statute also says that they can also approve physical searches, the use of trap and trace devices, and pretty much all electronic surveillance "to acquire foreign intelligence information for a period not to exceed 15 calendar days following a declaration of war by the Congress."

The fine print of the Selective Service Act comes into play

It's kind of mind-numbing to think about, but when the U.S. realized they were on the cusp of wading neck-deep into World War I, the only army the country had was one of about 100,000 volunteers. That led to the establishment of the Selective Service Act, which meant mandatory registration for many. Fast forward to World War II and Vietnam, and it would become a really big deal.

Part of the Selective Service Act outlines the requirements of service, saying that a certain amount of time in active duty is enough to lead to an honorable discharge and a fulfillment of service terms ... except in times of war. That's when things get tricky, and according to one statute that comes into play, once there's a formal declaration of war, it doesn't matter whether or not someone has served their time, and it doesn't matter whether or not they want to go home.

The Congressional Research Service points to this clause, which says those who make a voluntary enlistment can't be re-conscripted against their will, unless, as the Selective Service Act states (via the U.S. House of Representatives): "after a declaration of war or national emergency." It also says that exemptions that are normally applied to anyone enrolling for service into active duty don't apply, either, which basically means that when war is on, soldiers are going, even if they've already served their time.

The Sole Survivor Policy is no longer guaranteed

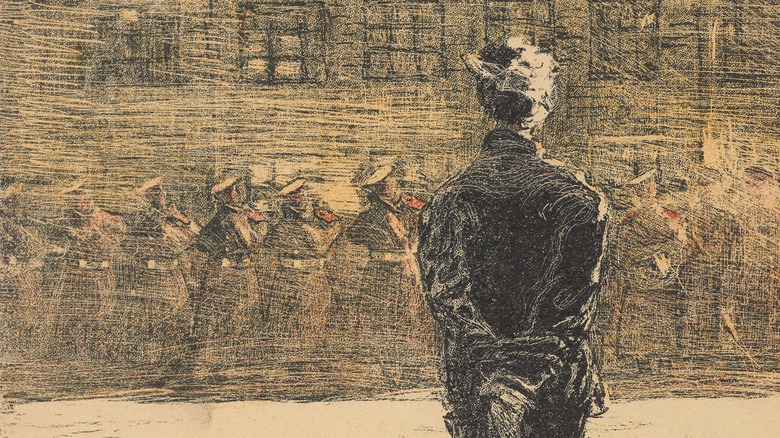

Ask anyone to name a war movie, and there's a good chance they'll go with "Saving Private Ryan." The Steven Spielberg classic is based on the idea of the sole survivor policy, which is more accurately called the Special Separation Policies for Survivorship. The idea is pretty straightforward, and it's put in place to try to ensure that a family doesn't lose all their children to active combat deaths. One of the most famous cases was the five Sullivan brothers, who were stationed together on the USS Juneau (pictured), and were all killed when it sank during the attack on Guadalcanal.

That's an awful thing for a family to have to deal with, and even more awful was the fact that it wasn't an abnormality: The Sullivan brothers were the most talked about, but the sinking of the ship actually killed at least 30 sets of brothers.

Official exemptions were put in place in 1948, and simply said that when a family has lost one child in military service, others would be exempted. That was later expanded, but it turns out that the protections only go so far. The official wording that's buried in the Selective Service Act says, according to the Congressional Research Service: "... the exception for those who have had a close relative killed in the line of duty does not apply 'during the period of a war or a national emergency declared by Congress.'"

Retirees can be recalled to active duty

Retiring from the military isn't just as easy as saying goodbye and riding off into the sunset, and Military.com says that there's a whole list of rules that vary quite a bit, depending on the branch of the military and what role a person has played. One of the big factors in recalling retired military members is the stop-loss, which effectively means someone's not so much recalled, but kept on active duty past their discharge date.

Once a war is declared, though, things change in a big way, and the Congressional Research Service points to a footnote in the rules governing how the various branches of the military recall retired members. They note that limitation periods on the recalling of retired military veterans and officers are waived once war is declared, and that's kind of an across-the-board sort of thing.

A closer look at various policies regarding a recall to active duty shows that there are a whole series of limitations that are, for the most part, put on recalls. (In some cases, officers are recalled into a higher grade than they retired in, time and age limits are in place, the number of active tours served are taken into consideration, and the number of paid officers in that particular grade already on active duty can impact who's brought back.) The bottom line, though, is that once war is declared, all that gets thrown out the window, and it's all hands on deck.

The death penalty is on the table for desertion

The 1945 death of Private Eddie Slovik is pretty heart-breaking stuff. The 24-year-old was shipped off to France and, in his first experience in active combat, knew he couldn't cut it. He took off, fell in with a group of Canadian soldiers, was handed over to the Americans, and given a second chance. After leaving again, he surrendered with a note that read, in part (via American Heritage), "I, Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik, ... confess to the desertion of the United States Army. ... I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out their again Id run away. He said their was nothing he could do for me to I ran away again AND ILL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THEIR."

Slovik was put on trial, then put in front of the firing squad: The 12 soldiers chosen to shoot him didn't make a clean kill of it, and he died as they were reloading. It might seem like that kind of punishment was left behind in the 1940s, but the potential to hand out the death penalty for desertion during wartime is still on the books.

The Congressional Research Services points to this clause, stating: "[desertion or attempted desertion] shall be punished, 'if the offense is committed in time of war,' by death or 'such other punishment as a court-martial may direct.'" In addition, a declaration of war allows for the death penalty to be handed out in other cases, too, including disobeying orders given by a superior officer, and falling asleep while on guard duty.

Industries and businesses can be seized

When the U.S. entered World War II, the overhaul of domestic industries was equal parts extreme and impressive. It didn't happen overnight and alone, and there was actually a War Production Board established to oversee a few things, including the retooling of industries to produce goods needed for the front lines, and the distribution of raw materials like rubber, metal, and plastic. Some of the industries impacted show some pretty impressive ingenuity: The Lionel toy company, for example, might not have been equipped to turn an entire battleship out of their factories, but they were able to produce smaller but essential items like compasses.

The War Production Board folded in 1945, but according to the Congressional Research Service, there are still laws that allow for the wartime seizure of domestic industries ... whether the owners of those industries agree to the takeover or not.

The exact wording, per the U.S. House of Representatives, says that the president can seize any business "equipped to manufacture, or ... is capable of being readily transformed into a plant for manufacturing, arms or ammunition, parts thereof, or necessary supplies for the armed forces." It doesn't matter if those in charge don't want to be retooling their plant to make weapons or other wartime necessities: If there's a war on and the president says so, that's what they're making.

The oceans aren't a lawful dumping ground ... except during wartime

It's no secret that the world's oceans are in a dire state, and there are all kinds of reasons for that. That laundry list of terribleness includes the consequences of decades' worth of wars: In 2022, research out of Belgium was published in Frontiers in Marine Science, and confirmed that World War II-era shipwrecks were still leaking contaminants into surrounding water, and damaging ecosystems.

This is far from a minor issue: From millions of tons of oil to ammunition, chemical weapons, fossil fuels, to the shipwrecks themselves, it's the sort of problem that exists on a ridiculous scale. While government agencies have done a lot to try to curtail dumping the world's garbage into the world's oceans, things kind of get put on hold when there's a declaration of war.

According to the International Maritime Association, the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, or MARPOL, was put in place in 1973, and it's been adopted and adapted a few times since then. The idea is to minimize pollution from ships, but according to the Congressional Research Service, U.S. law says that during wartime, U.S. ships don't have to abide by the principles put forward. Not only does it allow for the bypassing of pollution control standards, but it also allows U.S. ships to dispose of "potentially infectious medical waste" by dumping it into the ocean.