How Does A World War Happen?

In 2022, Russian forces have invaded Ukraine in support of separatists in the Donbass region. The Russian invasion sparked concerns of World War III, and according to Ukrainian activist Daria Kaleniuk (via MarketWatch), it has already started. The concern is real. Per NATO itself, should Russian troops attack NATO forces, the entire bloc would be obligated to intervene — and should it go nuclear, the consequences would be devastating.

To avoid a new global conflagration one must understand how world wars happen. These conflicts differ from others in scale and power of participants. But they are fought for the same reasons most wars are: the desire for territory, resources, military alliances, or global/regional primacy. These factors driving the Ukraine conflict all drove the World War I and World War II. Now, the situation of every war is unique, and there is no 1:1 correlation between current events and those of the past. But the past two world wars provide valuable historical lessons applicable to today's conflict in the hope that humanity might spare itself a new world record for the most destructive war in history.

Territorial ambitions

Territorial ambition is a common casus belli for starting wars. Extra land can be seized for prestige, resources, or space for excess population. Often, conflict can be mitigated if there is "virgin" territory abroad to expand into. A nation can export its excess population to the new land and obtain its needs ideally without fighting its neighbors back home. But once uncolonized land abroad runs out, nations inevitably will begin squabbling over territory abroad and at home, gradually escalating tensions until they explode into war.

According to the University of Arizona, there were several territorial conflicts that exacerbated the tensions prior to WWI. For instance, the Franco-German dispute over Morocco drove Britain and France closer together. Meanwhile, the Ottomans concluded their own alliance with Germany precisely because they feared Russian claims on their own territory (via Yale Law). The Ottoman fear was not ungrounded either, since according to Britannica, Britain, 'France, and Russia agreed to carve up the empire's territory into what is today the modern Middle East in 1915.

In the end the colonial disputes are considered a minor cause of World War I. But they were crucial in creating the system of alliances that was in place by 1907 and undermining trust between nations. Once the alliances were in place and room to expand ran out, Europe was a powder keg, as any nation that declared war would drag several more in with it.

Entangling alliances

Alliances start and escalate wars. If two belligerents each call one ally, the war is now a four-party conflict. If each ally calls its own allies, the original two-party conflict snowballs into a regional or global conflagration to include players uninvolved in the original dispute. For this exact reason, President George Washington warned Americans to stay out of European affairs and avoid entangling alliances (via the Library of Congress).

Washington's words rang especially true in 1914. World War I, per Britannica, began as a localized Balkan conflict between Austria and Serbia following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. In response to Austria's declaration of war, Serbia issued a memorandum appealing to Russia for support. Austro-Hungarian emperor Franz Joseph II appealed then to his German allies against possible Russian involvement.

This network of alliances blew the powder keg. Russia and Germany declared war on each other. Austria-Hungary in turn declared war on Russia in support of Germany. According to the Imperial War Museum and the LOC, Germany then attacked Russian ally France to pre-empt encirclement through Belgium. Belgium was allied with Britain, which joined France against Germany. A conflict over the small country of Serbia had snowballed into a pan-European war, despite the lack of German, Russian, or British interest in the Balkan country.

Arms races

The Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies notes that arms races can either promote peace or lead to war. The former argument posits that two nations armed to the teeth (for instance, with nukes) may forego war if the consequences are too great. But things can also go the opposite direction. If either side fears being overtaken, it may resort to war before it is outmatched.

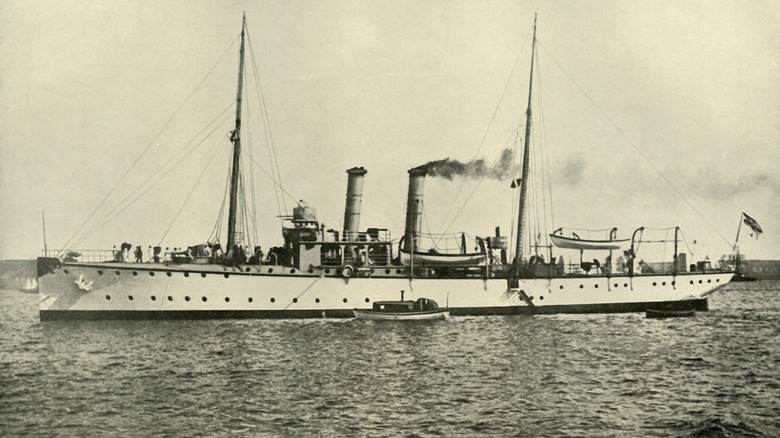

Per the Encyclopedia of the First World War, military spending ballooned in the early 20th century as states raced to obtain the latest weapons, such as tanks, airplanes, and machine guns. At sea, per the Imperial War Museum, Germany and Britain engaged in a naval arms race in the North Sea as the German navy was expanded to overtake the British fleet. Public demand, the press, and special interest groups in the shipbuilding industry, who made money churning out more ships, pushed both countries to accelerate militarization.

The IWM notes that although Germany gave up on its naval ambitions in 1910, the arms race undermined trust with Britain irreversibly. Britain, meanwhile, in part entered WWI to pre-empt further German naval buildup. After all, German defeat the French navy would have left Britain to fight the still-powerful Germany navy alone. A German victory in such a contest would have opened Britain to the possibility of economic blockade and a loss of its global power.

Bad treaties

Ideally, a peace treaty should promote reconciliation, but often, settlements tend to be harsh. These bring economic misery, wound national pride, and tend to create resentment amongst the defeated population. Often, this is exactly the goal — to completely break the defeated nation's ability to fight again. But if a vanquished country has the will and capacity to recover, revenge soon finds its way onto the list of priorities, especially if nationalists come to power.

According to the National WWII Museum, the two world wars stand out in that the second was a continuation of the first, mostly thanks to the Treaty of Versailles – the settlement that threw all the guilt for World War I upon a defeated Germany and demanded heavy territorial and financial concessions. Articles 87 and 88 forced Germany to hand over parts of its territory to the new state of Poland, section 5 ceded western territories to France, while articles 31-38 handed over territory to Belgium. German East Prussia (modern Kaliningrad) was left detached from the rest of the country by the infamous Polish corridor, and the city of Danzig was made a free city outside of German control.

The worst parts of the Versailles Treaty were economic. Under the Treaty of Versailles' financial clauses, Germany was ordered to pay reparations to the victorious parties. According to the BBC, they totaled to 100,00 tons of gold, a sum so large that Germany only finished paying in 2010. So it is no surprise that the resentment and the resulting economic pain created ideal conditions for Adolf Hitler to rise to power, as the BBC notes.

Irredentism

As Britannica explains, irredentism (from Italian irredento, meaning unredeemed) is the idea that a nation must incorporate members of its ethnic group that live outside its borders. Since the lands in question belong to other countries, usually, this must be accomplished by force or coercion. The ideology saw its heyday during both world wars, making it one of the major driving factors of both.

The two chief examples of irredentism in World War I involve Italy and Romania. According to Britannica, Italy, although allied with Germany and Austria, remained neutral. But according to Sheffield-Hallam's Matthew Stibbe, Italy coveted Italian-speaking territories in Istria, Dalmatia, and Friuli-Venezia-Giulia, which belonged to its Austro-Hungarian ally. The Entente Powers (Britain, France, Russia) exploited this desire with the 1915 Treaty of London, offering Italy these lands in return for attacking the Central Powers and expanding the war into the Mediterranean.

Romania entered WWI much the same way. According to the Bavarian State Library, the country remained split on whose side to take until the Entente powers offered King Ferdinand the Hungarian region of Transylvania. As Hungary Today notes, the region was 53% Romanian. But the 1920 Treaty of Trianon, which transferred Transylvania and 70% of Hungary to its neighbors, highlighted the irredentist problem in ethnically mixed areas. As the American-Hungarian Federation notes, around 3 million Hungarians, including 30% of Transylvania's population, were now minorities in states that viewed them with hostility. Unsurprisingly the tensions required German and Italian arbitration through the Vienna Awards during World War II to placate Hungary and avoid further conflict.

Political opportunism

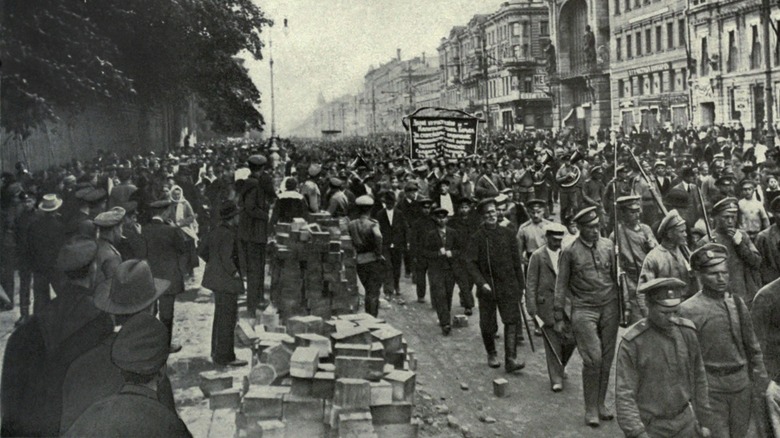

Wars cause hardship, instability and civil unrest at home, creating perfect conditions for revolution. Thus, political agitators often lobby for conflicts that might help them achieve their goals. No one understood this better than the virtually unknown communist agitator Alexander Israel "Parvus" Helphand. According to Turkish scholar M. Asim Karaömerli̇oğlu, Helphand hoped to make Russia ripe for communist revolution by helping manufacture a war that would bring the czarist government to its knees.

Helphand set out organizing a massive propaganda campaign. First, he and his agents encouraged pro-war sentiment and German nationalism against Russia, believing that a German defeat of Russia would allow him to stage his revolution. According to "Germany and the Revolution in Russia," he then single-handedly expanded the war with a massive press campaign to convince Bulgaria to enter on the side of Germany, while stirring up pro-war sentiment in Italy and Romania too. Once Russia could no longer sustain its war effort at home in the face of German pressure, Helphand seized his chance.

As Britannica notes, Helphand made Germany an offer: If Germany would help one Vladimir Lenin and his Bolsheviks seize power in Russia, Lenin would pull Russia out of the war. The result was the 1918 Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Russia was out as the communists began their campaign of terror to establish the USSR. While Helphand was not the sole cause of World War I, he is the epitome of how political opportunists can help start and expand wars to further their own agendas, with a catastrophic human cost.

Special interests

Wars are rarely fought solely for ideological purposes. In fact, ideology almost always takes a back seat to money and power, the root causes of most human conflicts. Modern wars in particular provide an easy way to profit from selling supplies to belligerent governments and paramilitaries. The world wars were no exception, exacerbated by the desire of industry to turn massive profits from sales of war materiel.

American Marine Corps general Smedley Butler in his pamphlet, "War is a Racket," opined that wars happen at the pleasure of rich men. The general noted that the American involvement in World War I was heavily driven by industrial interests, even if the U.S. had no reason to involve itself in the European conflict. American corporations raked in huge profits supplying Britain and France with material. DuPont made over $58,000,000/year selling gunpowder, while Pennsylvania's Bethlehem Steel raked in nearly $49,000,000 from 1914-1918.

But American corporations did not help Britain and France alone. Butler, an eyewitness to the era's events, noted that American industries cynically supplied both sides. After all, "a dollar is a dollar" regardless of whether it came from Germany or someone else. By 1917, American soldiers were dying on Europe's battlefields while the corporate bosses, who had lobbied for the conflict in the first place, continued to strike paydirt.

Economic crisis

As Forbes notes, wars are an easy way to revitalize a nation's production and reduce unemployment, since everyone is needed to produce necessary supplies, munitions, and provide recruits to build an army. Additionally, if economic pain is the direct result of a previous conflict, it breeds resentment and a desire for revenge that catapults more jingoistic-minded demagogues into power.

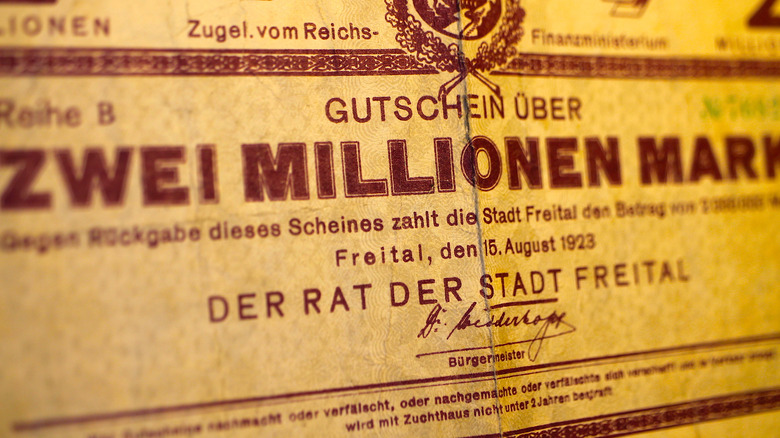

As noted earlier the Treaty of Versailles' financial clauses stuck Germany with massive indemnities it could not pay. So as the BBC notes, Germany printed money to cover its debts, resulting in hyperinflation that sent the prices soaring. Bread that cost 200 marks in 1922 was 200,000,000 marks by 1923. As Salon notes, survival sex work, especially among mothers and daughters, became commonplace.

According to the National WWII Museum, it is little surprise that when Adolf Hitler ran for office in Germany on promises to avenge Versailles, restore Germany's military strength, and revitalize the country's economy, he enjoyed significant popular support. This revanchism soon surfaced when Hitler began throwing Germany's weight against its neighbors, culminating in the 1939 invasion of Poland.

Japan suffered similar problems. According to Japan's National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, the Japanese economy tanked in the 1930s. The political gridlock opened a path for military rule, which swiftly launched an expansionist war into China. The conflict put the Japanese economy on a war footing, reducing unemployment and revitalizing industrial production, but it came at a cost. With its invasion of China, Japan had ignited World War II in Asia.

Shortages

Economic necessity is one of war's immemorial causes that is often closely tied with territorial expansionism. Territorial conquest begets military expansion to secure new land, which in turn requires additional resources. If a resource-poor state cannot sustain expansion with available resources, it may take them from someone else. This exact problem led 1930s Japan to open the World War II's Pacific theater.

As the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, Japan invaded China in 1937, placing its economy onto a war footing. Soon, per the Imperial War Museum, Japan encountered a major problem. It lacked enough oil to fuel its navy and aircraft. But there was plenty to go around in the British colonies of Southeast Asia. A Japanese attack on British Southeast Asia, however, would likely trigger a U.S. response.

Japan took a major gamble. Per Britannica, Japan allied itself with the Axis powers of Germany and Italy in 1940, hoping to deter American intervention in the Pacific. It followed this up with the 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor, intended to cripple the U.S Navy. Japan's actions had the opposite effect, opening an additional front in the Pacific against the U.S. that it was not prepared to fight. According to the U.S. Capitol, Germany and Italy declared war on the U.S. in support of their Japanese ally, and World War II, up to then a European conflict, truly became a "world war."

Secret Treaties

Secret treaties are unfavorably seen today, but as Anglo-American journalist Alfred Maurice Low noted in the North American Review, they were all the rage in the first half of the 20th century. Secret treaties are useful for powers to furtively coordinate expansion against smaller neighbors. After all, it is much easier to start a war against an unprepared foe than a fully mobilized one.

German dictator Adolf Hitler realized this, so as Harvard University notes, he sought a secret co-conspirator -– his archenemy Joseph Stalin– to aid him in his blitzkrieg against Eastern Europe. In 1939 the two dictators engineered the start of World War II with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (signing above). Publicly, the document was a non-aggression pact. But it also included a secret arrangement (via the Wilson Center) to carve up Eastern Europe. Western Poland went to Germany, while Eastern Poland and the Baltic went to the USSR.

The secret protocols did two things. First, it condemned the Baltic and Poland to Nazi-Soviet aggression and rule. Second, it gave Hitler the security he needed to invade Poland, since the USSR would actively assist him, unbeknownst to Poland's British and French allies, who according to History Extra, were only expecting Germany to attack Poland. With this secret pact, Hitler and Stalin ignited the bloodiest war in human history, sweeping aside their Eastern European neighbors, who, caught alone in the Soviet-German pincer, had no time to prepare meaningful resistance.

False flag ops

According to Britannica, the UN Charter permits armed conflict under a casus belli of collective or individual defense. Now, even before the founding of the UN, governments have sought casus belli to justify wars to the international community and to their own people. When unavailable, governments may create one through false flags. Per Merriam-Webster, a false flag involves the commission of a hostile action to be blamed on an opponent, usually to justify a war.

This operation is exactly how World War II started when Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin needed to justify their Eastern European adventures in 1939. In September of 1939, Polish forces attacked a German radio tower in what became known as the Gleiwitz Incident. Or so it seemed. According to the Proceedings of the Nuremberg Trials (via Yale Law), it turned out that Germany had false-flagged Poland in August of 1939. Dressed in Polish uniforms, German soldiers attacked their own radio tower. But it was enough for Germany and its Soviet allies to justify the subsequent invasion in September.

The Soviets repeated this operation in November of 1939. According to Finland at War, on November 26, 1939, Soviet forces invaded Finland in response to Finnish shelling of their lines near Mainila. The bloody conflict known as the Winter War followed. As the BBC notes, however, Finland had no reason to attack the much more powerful USSR, making it likely that the Soviets had shelled their own lines and blamed the Finns for it.

Decline of a superpower

When a great power declines, smaller rivals tend to pounce, yet another common cause of war since time immemorial. But today, as Tufts University notes, the world is unique in that there is only one superpower –- the United States. However, American rivals Russia and China have both shown interest in replacing the U.S. as world powers and have the potential to ignite a new world war.

In 2015, Time Magazine suggested that World War III would pit the U.S. against China, which has challenged American hegemony in Asia, Africa, and Latin America through military expansion and economic investment. As Newsweek and War on the Rocks note, Russia has done the same in Latin America and Central Asia.

ABC has quoted Vladimir Putin referring to the U.S. as a power in decline, a victim of mistakes "typical of an empire." Presumably, Putin is referring to the weakening U.S. economy and its wars in the Middle East, which have indebted the U.S. and caused division and pain back at home. Should American dominance end, as Putin assumes, the world will revert to a multi-polar state. A hot World War III will likely decide whether Putin's prediction is correct, and Russia (and presumably China) may not find a better opportunity than now to overthrow American hegemony.