The Biggest Controversies From FDR's Presidency

Franklin Delano Roosevelt was a president both beloved and reviled. He was the only president to successfully break George Washington's two-term precedent and win a whopping four terms. He can also be considered the political father of the American welfare state — including Social Security, a key issue in virtually every national election that neither party dares touch. Among strict constitutionalists, however, he is viewed as an abuser of federal power who attempted to rig the Supreme Court when things did not go his way.

None of these criticisms are exactly new. Roosevelt's presidency was quite turbulent, and not just because of World War II. It was filled with lawsuits as opponents of his New Deal programs lined up to challenge them before the Supreme Court. On the foreign policy front, he was criticized for being too conciliatory towards communism. Despite the many controversies, they never seemed to dent his chances come election — he won all of them (1932-44) handily, including two landslides.

Recognizing the USSR while it was genociding Ukrainians

Franklin Roosevelt was often branded a communist sympathizer, and his policy towards the USSR did not help him. The communist state, which rose out of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, received American recognition in 1933.

The president justified his decision on economic and strategic grounds, arguing the United States would have a partner in countering Japanese expansion in the Asia-Pacific region, while also providing a business opportunity to American companies. Even anticommunists such as Henry Ford supported that, having struck a deal to make cars in the USSR in 1929.

While American political and business interests supported recognition, opposition worried it would embolden Soviet agitation in the U.S. Organizations such as the American Communist Party were already following a Moscow-set agenda, while businessmen such as Armand Hammer lobbied politicians on the Soviets' behalf. There was also the moral issue: The USSR was actively engaging in genocide.

The Holodomor was a Soviet-induced famine in Ukraine that killed between 3-7 million Ukrainians. The official White House position, per Ray Gamache, writing in Harvard Ukrainian Studies, was that Roosevelt was unaware of the Holodomor. Yet, a series of Roosevelt's statements suggest the opposite. He even met with New York Times journalist Walter Duranty, who became notorious for covering up the famine. Soviet recognition, Gamache argues, effectively gave Roosevelt's blessing to the Soviet use of famine as a political weapon.

The 1933 gold policy

Among Franklin Roosevelt's most consequential policies was Executive Order 6260, signed on August 28, 1933, which ended the circulation of U.S gold currency. Before 1933, banknotes could be redeemed for precious metals, while gold coins circulated as legal tender in accordance with Article I, Sec. 10.1 of the Constitution.

The EO ordered Americans to surrender all gold certificates and coins in excess of $100 (with a few exceptions) to the nearest Federal Reserve branch within 15 days of the order. It then banned individuals from owning gold bullion, which became property of the U.S. government under the 1934 Gold Reserve Act. Violators faced a $10,000 fine, 10 years in prison, or both.

In return for their gold, Americans received monetary compensation. Had the price of gold remained steady, some uproar might have abated. But as soon as the U.S. government had taken the gold, the dollar became devalued, and the value of gold increased. So Americans lost money, while Washington saved $50 billion.

The order triggered several Supreme Court cases, two of which argued that the EO violated the 5th Amendment's provision against confiscation. The plaintiffs lost after SCOTUS ruled that the government had paid out fair compensation per the certificates' face value according to the price of gold at the time, just as the documents called for.

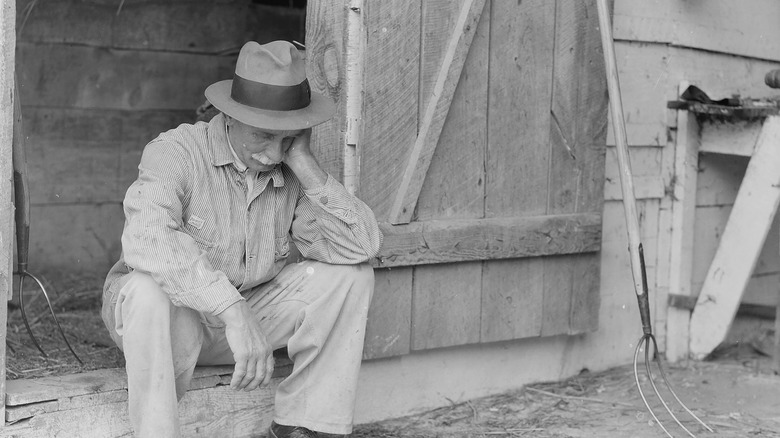

Paying farmers not to grow crops

In 1933, Congress passed and Franklin Roosevelt signed the Agricultural Adjustment Act, which addressed a series of agricultural supply and demand issues from after World War I. The U.S. agricultural market had experienced a boom following the war thanks to technological improvement and farmland expansion. The excess produce was sold to Europe, whose production had been kneecapped by World War I. But once European agriculture recovered, it did not need American imports. Production, however, continued apace, creating an agricultural surplus that caused prices to plunge, even before the Great Depression.

The Agricultural Adjustment Act was the Roosevelt administration's attempt to force prices back up to pre-World War I levels. The legislation paid farmers not to produce more than a certain amount of their products and destroy any excess. A tax on middlemen purchasers of agricultural products funded the subsidies. Scarcity, market logic dictated, would raise prices.

The act did help raise agricultural prices but it faced criticism on two counts. First, it was passed during the Great Depression, when nearly a quarter of Americans were unemployed. For those still employed, wages had fallen nearly 43%. This translated to food insecurity and bread lines for people who could not afford the higher prices. Meanwhile, middlemen challenged the subsidies tax before SCOTUS in 1936, which struck the act down in U.S. v. Butler. The majority ruled that Washington had exceeded its authority by encroaching on states' right to regulate agriculture.

The displacement of the Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority was a New Deal-era public utility created to build and maintain hydroelectric dams and plants in the Tennessee River system. The project would create jobs and provide electricity to the poorest parts of the rural South. But as with most New Deal projects, it encountered opposition, this time among inhabitants of the affected areas.

The project displaced 72,000 people. Although rural poverty was endemic to the Tennessee River Valley, many of its inhabitants had lived on their small farms for generations. The increase in standard of living the TVA brought did not seem worth giving up their property for reservoirs. Ultimately, the TVA ended up taking them anyway through eminent domain. The government would give them a "fair price" for their land -– except the government got to define "fair."

Norris, Tennessee, is a good case study. Displaced residents interviewed in 2012 by KnoxNews recalled only receiving compensation for their families' graves — not their properties. A few were even evicted from their new homes for other TVA projects, or in the case of one man, to make way for the Oak Ridge nuclear facility. But, they admitted, in the long run, the TVA had been a net boon to the region.

Then there were the power companies, who feared the TVA would undermine competition and their profits. Led by Wendell Willkie, they sued, alleging the TVA was an unconstitutional government monopoly. Although they lost, Willkie gained national attention that catapulted him to the 1940 Republican nomination.

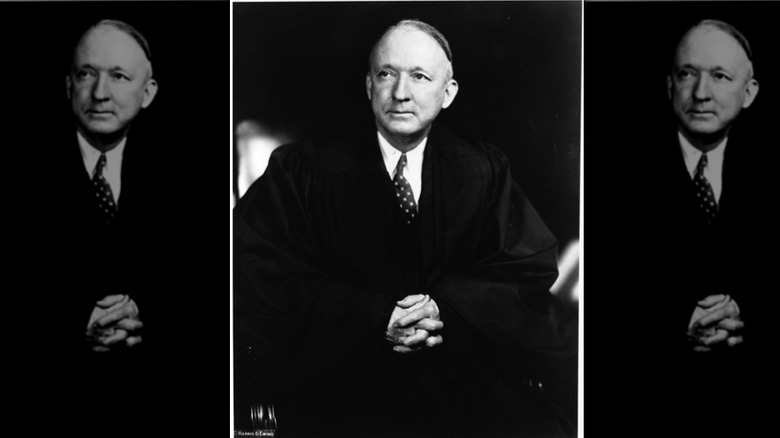

Nomination of Hugo Black to the Supreme Court

Hugo Black made his name as an Alabama lawyer and U.S. senator. In 1937, Franklin Roosevelt nominated him to the Supreme Court, and Congress confirmed him. But when the press found out he was a former Ku Klux Klan member, it started an uproar.

The Pittsburgh Gazette got the ball rolling in 1937, accusing Black of joining the Klan for two years, quitting in 1925, and getting a "Golden Grand Passport" with the organization. More exposés followed, leading to calls for Black to resign. Roosevelt immediately distanced himself from the justice, despite Black's New Deal support, while some senators said they would have never confirmed him had they known about the Klan ties.

Black did not respond immediately to the charges. Instead, according to the Supreme Court Historical Society, he hired a female, Catholic stenographer and African-American (possibly Catholic) messenger. These details then went public, suggesting Black's office leaked them to showcase his opposition to the Klan's racial and religious views. He topped it off with a radio broadcast decrying anti-Catholicism and anti-semitism, adding he had many African-American friends.

Ultimately, Black was able to defend himself on the basis of his record. He had made his name by representing an African-American man who was given extra prison labor beyond his sentence. The Klan membership, he claimed, was at the advice of a Jewish friend for political advancement. In 1920s Alabama, a Klan endorsement was a virtual guarantee of electoral victory. He would later vote to overturn Jim Crow segregation laws in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education.

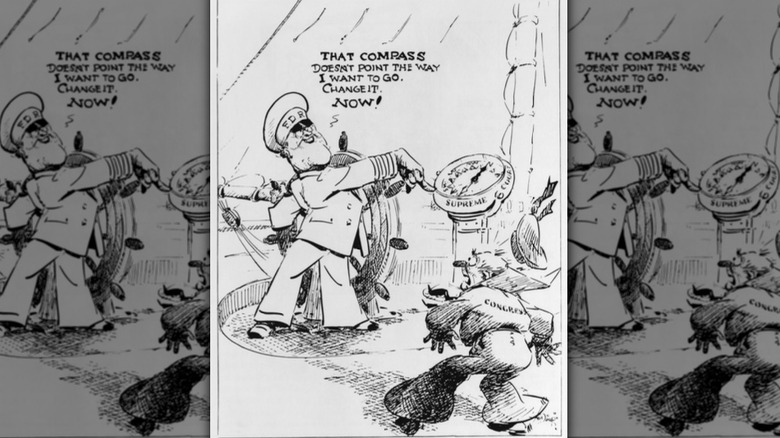

The 1937 court packing scheme

Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal repeatedly ran into problems with the Supreme Court thanks to four conservative justices who were also the biggest opponents of the New Deal. Wanting to move forward on such programs as social security, FDR hit upon an idea: add extra SCOTUS justices to get a few more votes.

Roosevelt's plan called for Congress, which the Democratic New Deal Coalition controlled, to pass the Judicial Procedure Reform Bill. The bill would have allowed the president to appoint a new justice for every member of the court over 70. The makeup of the New Deal-era court meant an expansion of the SCOTUS bench from nine to 15 justices and a presumed 9-6 majority in Roosevelt's favor.

Although Roosevelt tried to sell the plan as strengthening the court to better serve the people and the Constitution, Americans weren't buying. Roosevelt also had not counted on opposition from SCOTUS liberals and his own party. Montana Democrat Sen. Burton Wheeler slammed the plan, calling it a very misguided. Even liberal Justice Louis Brandeis signed a letter alongside his conservative colleagues accusing the president of infringing on the court's independence.

Funnily enough, FDR did not end up needing to pack the court. Social Security — a signature part of the New Deal — passed the constitutional muster and talk of court packing died down.

The anti-lynching fiasco

As the 1940 presidential election approached, Vice President John "Cactus Jack" Garner was gunning for the presidency. Franklin Roosevelt was expected to step down after two terms, so Garner believed he had a lock on the nomination and the strategy to counter a Republican resurgence.

Garner realized he could implode the Republican strategy by courting the urban African-American vote, which had historically voted red. He figured he could accomplish the flip by supporting a congressional anti-lynching bill –- even though he had opposed it before. He would get Roosevelt to support the bill and pass it through a simple majority Senate vote. The president would sign it, leave office, and leave 1940 to Garner.

But Garner did not factor in FDR's stance. The president refused to endorse the bill because he was preparing a third presidential run. Not wanting to alienate Dixiecrat voters, he stayed mum, despite criticism from some northern Democrats, the NAACP, and his wife Eleanor. Instead, he let Garner take the heat for his vote-buying about-face, clearing out his only possible opponent for the 1940 nomination. FDR's stance was no surprise. He had previously said that supporting any anti-lynching legislation would ensure Dixiecrats blocked virtually any bill he sent before Congress.

Breaking the George Washington precedent

In 1940, Franklin Roosevelt did something only Teddy Roosevelt had ever done –- he decided to run for a third term, breaking George Washington's 1797 two-term precedent. Roosevelt justified his decision, pointing out that the escalation of World War II might require U.S. involvement and consistent leadership. Despite the uproar, there was nothing illegal about Roosevelt's third run –- the 22nd Amendment limiting presidents to two terms had not been passed yet.

FDR faced Republican Wendell Willkie, a former New Deal Democrat who had fallen out with Roosevelt over the Tennessee Valley Authority and possible American involvement in World War II. Willkie's campaign, which mostly supported the New Deal, made keeping America out of war –- not Roosevelt's third presidential run –- the central issue. This worked, allowing the Republican to close the public opinion gap with the president.

The RNC, however, assailed Roosevelt's third run, summing up its concerns in a five-point pamphlet, arguing that a third Roosevelt term would set a dangerous precedent for future presidents to serve unlimited terms and eventually declare themselves dictators in opposition to the founders' intent. It also cautioned that the federal bureaucracy that the New Deal had created would entrench themselves in Washington.

The campaign utterly failed and may have cost Willkie the election, as FDR crushed him 449-82. Once Republicans retook Congress after the war, their first priority was the 22nd Amendment, ensuring no future president would be able to surpass FDR's four terms.

Japanese internment camps

Following Japan's December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. entered World War II on the Allied side. Among the first priorities was identifying possible fifth columns within the United States. To that end, Franklin Roosevelt's Proclamation 2527 allowed the U.S. government to detain and expel non-naturalized Italian and Japanese citizens who might prove security threats.

By February 1942, however, things escalated with Executive Order 9066. The order was twofold — it allowed the secretary of war to determine which parts of the U.S. were "military areas." Then, the office was to decide who would be allowed to live freely within them, who would be excluded and removed, and who would be forcibly detained inside them.

As a result, 100,000 Japanese Americans, around 11,000 German Americans, and a few Italians were moved to internment camps. They suffered property and business losses and even prosecutions for tax evasion over sums they could not pay while interned.

The order went before the Supreme Court in Korematsu v. U.S. on the grounds that "his [Fred Korematsu's] right to liberty was being infringed by military action without due process of law." The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Roosevelt administration, finding that in wartime, the U.S. had the right to take extraordinary measures against espionage and foreign invasion in the areas closest to the hostile power. The internees had to wait until 1988 for compensation when Ronald Reagan's Civil Liberties Act apologized and offered them $20,000 each.

The failed 100% supertax of 1942

The New Deal and World War II were in part funded through across-the-board tax increases. At one point, Roosevelt decided to try and cap income of upper earners to $25,000 through a 100% "supertax" via Executive Order 9250 in 1942.

The "supertax" was not a tax on all income. It was a marginal tax that would take 100% of every dollar earned over $25,000 on individual incomes that were over $67,200. For married couples, the limit would have been $50,000. The president justified the tax in a letter to the House Ways and Means Committee, arguing that war taxes should be equitably distributed by forcing the wealthy to turn over their excess cash to support the war effort.

In the end, the letter suggests that Congress rejected FDR's "supertax" and shot down the executive order. Instead, they compromised. FDR got an 88% marginal tax rate on incomes over $200,000. By 1944, the marginal rate on top earners had gone to 94%. However, there was another controversy. Originally, the federal income tax had only applied to approximately 10% of the American population -– the wealthier echelons. As a result of FDR's tax changes to fund the war, it came to apply to over 90% of the American population, which were largely the middle class and the poor, with a 23% rate by 1944.

The betrayal at Yalta

The February 1945 Yalta Conference brought together Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt (above center), and Winston Churchill to discuss post-war Europe's future. The parties agreed that postwar Eastern European governments would be accommodating to the USSR, which promised to allow free elections. But the Soviets did not cooperate as planned.

Poland was Yalta's central issue. According to Polish outlet TVP World, Roosevelt and Churchill recognized the Soviet-backed Polish communist junta over the Polish Government-in-Exile in return for free elections. These never materialized, and the USSR seized half of Poland's territory. Expropriations, murders, and deportations followed as Poles accused Roosevelt of betrayal.

Opinions regarding FDR's complicity are split. Jim Bishop's account in "FDR's Last Year" cited an eyewitness who said the ailing president looked like "a fighter ... after a mauling." When told that Yalta was a gift to the Soviets, he responded, "I know. But it's the best I can do for Poland at this time."

On the other hand, critics have pointed out that Roosevelt may have been under undue influence from Alger Hiss, later unmasked as a Soviet spy. Hiss told The New York Times that he went to Yalta as an advisor, solely in relation to the creation of the United Nations. But it is hard to believe that Hiss, who had been credibly accused of espionage since the 1930s, would not have tried to stack the deck in Stalin's favor. The question is how much Roosevelt knew and whether leaving Hiss behind would have changed anything. Probably not much, since two months later, the president was dead.