What Abraham Lincoln's Funeral Was Really Like

Thomas J. Craughwell was a historian and the author of "Stealing Lincoln's Body," and once wrote of Abraham Lincoln's funeral, "There were so many memorable moments along the way that it would be the labor of a lifetime to catalog them all." And that's not entirely surprising: Sure, there was no social media or internet to spread news and photos fast, but for a country still reeling from the division and death of the Civil War, the assassination of the president sent countless people reeling — and searching for ways to process grief and shock.

Lincoln's funeral was a massive, sprawling event that meant stops at major cities across the northwest, and all the logistical issues that went with that. There was such a clamour to be a part of the ceremonies that honored the fallen president that cities fought over the right to host Lincoln's funeral train at stops along the way to his final resting place. There was a fight of fighting over that, too: It was ultimately chosen by Mary Todd Lincoln, as she recalled her husband's request to be buried in a peaceful, countryside setting.

The somber proceedings started with two periods of lying in state — starting on April 18 and 20 — first in the White House, and then in the Capitol. Documents preserved by the American Battlefield Trust describe the air of sorrow and grief that settled over the city. So, what was it truly like to witness the last journey of America's beloved Abraham Lincoln?

The funeral was a sharp contrast to the city days before

President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, 1865, just 10 days after Washington, D.C., had been seized by celebration. Confederate troops had abandoned Richmond, Virginia, and Lincoln was there to make the city the new military headquarters for the nation. The famous surrender at Appomattox came a few days later, and then? Grief.

One of the most fascinating insights into the earliest hours of Lincoln's funeral comes from Henry Brewster Stanton, who regularly moved in the presidential circle alongside his abolitionist father of the same name. He was literally standing front and center as they loaded Lincoln's body — bound for the White House — into a hearse, and wrote that he followed the little procession all the way. And it was a surprisingly little procession.

Stanton wrote (via The Lehrman Institute's Abraham Lincoln's Classroom): "At the east gate of the White House, there were soldiers and no one was admitted to the grounds. ... This absence of a great crowd on such an occasion was not due to any want of interest or lack of sympathy, but was rather caused, it seemed to me, by the terrible shock that had passed over the city, and because every one was so depressed that few had the desire to rush forward to form or join a crowd." He wrote that those who did turn up lined the way, close enough to touch the hearse, and sobs filled the air.

Preparations took several days, and grief was all-encompassing

Abraham Lincoln famously returned to Springfield, Illinois, for his burial, and the logistics of organizing the funeral were wildly impressive — especially considering there weren't many options for high-speed communication way back in the late 19th century. After Lincoln was assassinated on April 15, 1865, his coffin was closed in preparation for burial on May 4. In between, he traveled 1,645 miles through 400 towns in seven states. Preparations for all of that took just four days.

Journalist Noah Brooks wrote about the sense of widespread grief and mourning that had settled over Washington, D.C. All businesses closed, flags flew at half mast, and "Nature seemed to sympathize in the general lamentation, and tears of rain fell from the moist and comber sky," he wrote (via Abraham Lincoln's Classroom). "The wind sighed mournfully through the streets crowded with sad-faced people, and broad folds of funeral drapery flapped heavily in the wind ..."

Preparations also meant ensuring the president's body remained in a state for viewing, and that meant the application of a new-fangled technology: embalming. In a heartbreaking twist, Lincoln's body was prepared by the same doctor who had embalmed his beloved son, Willie, in 1862. While those who saw Lincoln's body early in the journey remarked on how lifelike he remained, that wasn't the case by the time it reached New York City. By then, New York Evening Post editor William Cullen Bryant observed (via The Washington Post), "the genial, kindly face of Abraham Lincoln [was but] a ghastly shadow."

Thousands passed through the White House to pay their respects

The first stop that Abraham Lincoln's body made on the way to his final resting place in Illinois was the White House, where his remains were installed for viewing on top of a black catafalque — which is basically just a fancy way of saying a platform. The Lehrman Institute's Mr. Lincoln's White House recalls the difficulty in the construction of the platform, saying that some close to the family issued a heartbreaking complaint: "Mrs. Lincoln is very much disturbed by the noise. The other night when putting them up every plank that dropped gave her a spasm and every nail driven reminded her of a pistol shot."

The noise so deeply and understandably impacted her that she insisted workers wait until she left the White House before removing the catafalque and viewing platforms. An estimated 25,000 people passed through the East Room to bid their farewells, and the proceedings were documented by the journalist Noah Brooks. He described Lincoln's body resting 15 feet off the ground, swathed in black, surrounded by flowers, and watched by an honor guard.

Sitting alongside Lincoln was General Ulysses S. Grant, who wept openly throughout the viewing and the sermon. Interestingly, representatives from numerous churches were not only in attendance but spoke at the funeral, including Episcopalian, Presbyterian, Baptist, and Methodist. Not in attendance? Mary Todd Lincoln, who was too distraught to attend.

Lincoln was the first president to lie in state at the Capitol

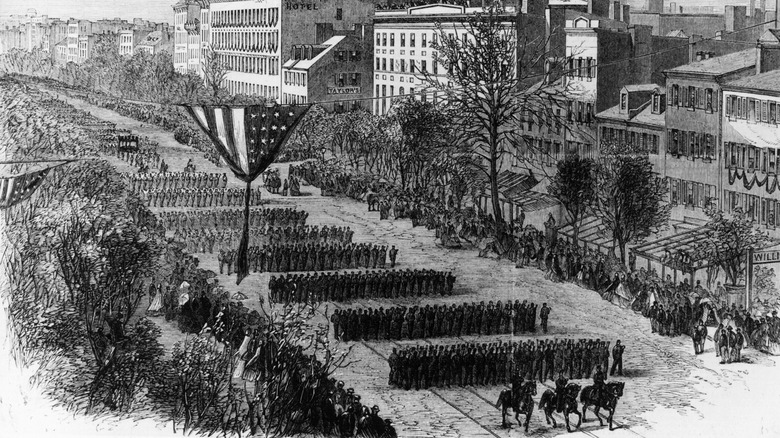

Abraham Lincoln was moved from the White House to the Capitol, in a procession that included six white horses and a procession of Union soldiers — led by a group of Black soldiers. Bringing up the rear were around 40,000 recently freed Black men, women, and children, in a solemn procession described in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper (via Mr. Lincoln's White House): "Despite the enormous crowd the silence was profound. It seemed akin to the death it commemorated. ... A solemn sadness reigned everywhere."

William Gamble, an officer with the Union army and supervisor of the honor guard that stood watch over Lincoln in the Capitol, recalled: (via Abraham Lincoln's Classroom), "It seemed as if a million of people had assembled and that Washington was a living mass of human beings of all kinds, shades, and colors. I have never dreamed of such a sight before and never expect to witness such an assembly again."

Gamble's eye-witness account is as heartbreaking. He wrote that while he stood watch, he saw the full spectrum of responses: Many cursed, more cried, and occasionally, they tried to reach out and touch the dead president. He wrote of one older woman who leaned forward to kiss him, quickly: "I could not find it in my heart to say a word to her, but let her pass on as if I did not see it. You can form no idea of the scenes I saw."

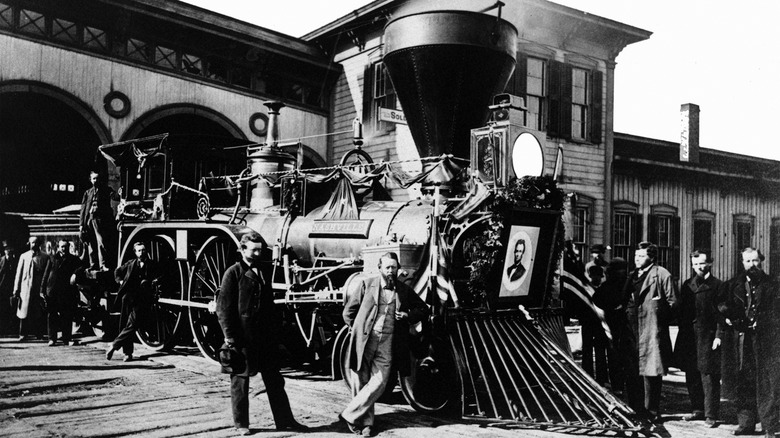

Lincoln's funeral train made a shockingly long journey, starting in Baltimore

After several days in Washington, D.C., Abraham Lincoln's body was moved to a funeral train, and sent on to a final destination of Springfield, Illinois. The first stop along the route was Baltimore, where his body was on display for about an hour and a half. Those who accompanied the president on his final journey remarked on the sheer outpouring of grief, and to demonstrate just how devastated they were, the city offered an additional $10,000 to the reward that had been put out for the apprehension of those involved in the assassination. Adjusted for inflation, that's about $202,000 in 2023.

From there, it was on to Pennsylvania, where all state governors began opting to ride along on the train. The somber procession headed through New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Indiana, and on to Illinois, and throughout the journey, eyewitness reports were very similar.

Entire cities — even those that the train only passed through — were draped in mourning colors, the tolling of bells and the singing of dirges filled the air, and crowds were eerily silent ... save for the sobs. Mourners arranged themselves in an orderly fashion, and in some places — like Buffalo, New York — mourners even marched in a procession that just sort of happened. And in Albany, as the train approached, a group of legislators who had remained steadfastly opposed to emancipation changed their minds in honor of the fallen president.

Abraham wasn't the only Lincoln that made the journey

There were around 150 people who rode on Abraham Lincoln's funeral train, but Mary Todd Lincoln was not among them. She didn't attend any part of the funeral, and those few who saw her reported her absolute devastation at events as they unfolded. One reported (via Biography), she was "more dead than alive — broken by the horrors of that dreadful night ..." As insistent as she had been that her husband's final resting place would be in Springfield's Oak Ridge cemetery, she also refused to move back there.

There was, however, another Lincoln who journeyed with him: Willie Lincoln. Lincoln family seamstress Elizabeth Keckley would later write of the devastation that 11-year-old Willie's 1862 death had brought the family, quoting Abraham's reaction to his death days after being diagnosed with typhoid fever (via The Washington Post): "My poor boy. He was too good for this earth. God has called him home. I know that he is much better off in heaven, but then we loved him so. It is hard, hard to have him die!"

After his death, Willie had been placed in a temporary vault with the idea that once his father's presidency was over, they would return to Illinois as a family. And they did: Willie's casket was placed in the train even before his father's, and they made the journey side-by-side.

Descriptions of the crowds are incredible

Abraham Lincoln's assassination came on the heels of the Civil War, the conflict that tore the country apart over slavery, and New York Tribune writer Charles Page observed (via History) that people were united in grief, and "[un]conscious of any difference of color." The mourning went on for days, and a fascinating example of that is Buffalo, New York. Buffalo (along with other cities) had initially staged a display of public mourning on April 19, with residents turning out to a funeral procession that escorted an empty coffin through the city. When the funeral train stopped there on April 27, everyone turned out again.

Reports of the crowds (like the New York City crowds, pictured) that turned out to view the fallen leader are almost unimaginable: The Philadelphia North American and United States Gazette reported that mourners filed past at a rate of about 80 per minute, while a chorus of 1,000 serenaded with funeral songs. Hours went by, and the crowds just didn't diminish.

For all the accounts of grieving crowds, perhaps one of the most poignant is a story told by The New York Times. It tells the tale of a St. Bernard who belonged to a man named Edward H. Morton, Esq., who reportedly pulled free and ran out to escort the funeral car as it moved down the street. The dog — named Bruno — was said to have met the animal-loving Lincoln prior to his death, and joined in to pay his own respects.

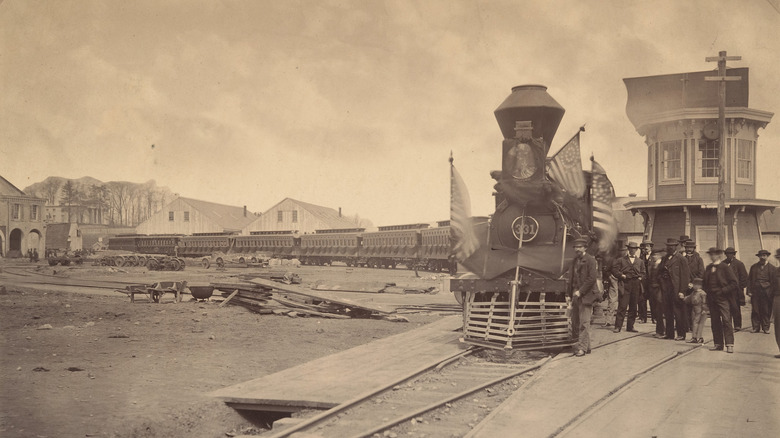

Crowds lined the tracks of the train's route

Since many newspapers published the itinerary of Abraham Lincoln's funeral train, Americans knew when it was going to be passing through their area. Even if they weren't in one of the major cities where it stopped, thousands and thousands of people still turned out to pay their respects in a very poignant, beautiful way.

The train averaged only about 20 miles per hour as it passed through populated areas, and as it chugged along — both through cities and towns, and through the countryside — it glided down tracks flanked by thousands of grieving Americans. There were families, there were mourners mounted on horseback, there were entire choirs singing funeral songs and hymns as the train passed, musicians who turned out to play dirges, and armed mourners who fired salutes. Clad in mourning clothes, some waved black scarves, and held bouquets of wildflowers. Since stops in cities coincided with daytime viewing hours, much of the travel was done throughout the night. Torches, lanterns, and bonfires were lit along the tracks, as if guiding the train along.

The train did stop in cities, towns, and stations where there wasn't a public viewing organized, and even then, grieving people turned out en masse. Many stops had small groups that were organized and allowed on the train, leaving flowers and tokens on the president's casket.

Lincoln's funeral train finally reached Springfield, Illinois

When Abraham Lincoln's funeral train finally reached Springfield, Illinois, city buildings weren't the only center of activities. At the time of the assassination, the Lincoln home was being rented by another family, and it fell to them to open their doors to thousands of grief-stricken mourners. Lincoln's actual casket was on display at the State House, and after 24 hours, he was moved for one final procession to Oak Ridge cemetery. By the time Lincoln's casket got there, his son's was already waiting for him.

The day itself was almost unbearably warm, and one of the things that stood out to onlookers and eyewitnesses was the smell of lilacs: Bushes were in full bloom across the city. But lilacs were in use for another, less poignant reason. Even as newspapers began to report on the decidedly sunken, shallow look of the president's body, his embalmer, Charles Brown, struggled to hide the inevitable decay beneath more makeup and perfume made from lilacs, strong-scented flowers chosen to help cover the smell.

Lincoln's body was escorted to Oak Ridge not only by human mourners, but by an animal one as well: Following directly behind him was his beloved horse, Old Bob. Mourners were still making their way to the cemetery when the services finished, then the gates were locked on the temporary vault (pictured) and Lincoln was alone with his son.

His Springfield, Illinois, entombment wasn't the last

When Abraham Lincoln's funeral was held on May 4, 1865, that actually wasn't the end of things. Lincoln's body has actually been moved a whopping 17 times, over fears he was going to be a target for grave robbers and body snatchers. Was he? Yes.

At the time, the grave-robbing trade was alive and well in America. Grave robbing was driven in large part by the medical industry for a number of reasons, but Lincoln was perhaps predictably a unique case. There was at least one fully-fledged plot to steal Lincoln's body and hold it for ransom, and it was the brainchild of a gang of Chicago counterfeiters. The Secret Service put an end to that plot, but it made it pretty clear that a permanent solution needed to be found.

For starters, that included a group of civilians organized specifically to guard the beloved leader's body. Over the course of almost two decades, Lincoln's remains were moved to secret locations and carefully guarded, until Robert Todd Lincoln insisted that a final memorial and monument be constructed. On completion in 1901, there were questions about whether or not he was still in the casket, so they decided to open it. He was: A group of witnesses confirmed that yes, Lincoln actually was in the casket, which was then entombed beneath two tons of concrete. Interestingly, the last surviving member of that group of witnesses is believed to be Charles Beaver, who died in 1966.

Want to look at photos? Check out JFK's funeral

Abraham Lincoln continued to shape the country even in death, starting with the fact that he was actually the one who helped popularize the kind of funerals many Americans have today. According to Elon University's Brian Walsh (via The Conversation), embalming was initially a procedure reserved for soldiers. Abraham Lincoln helped move that procedure to the mainstream.

Ripples were also felt in 1963, with the assassination of another president. After John F. Kennedy was killed in Dallas, Jackie Kennedy instructed that the funeral follow the same plan as Lincoln's. The two presidents were even lying in state on the exact same catafalque in the exact same room in the White House, and when it came time to move JFK to the cemetery, the same horse-drawn wagon was used. Also present? The riderless horse: The role played by Lincoln's beloved Old Bob was filled by a horse called Black Jack in JFK's funeral. (Want to learn more? Check this out to learn about what JFK's funeral was really like.)

Abraham Lincoln's funeral was designed to help an already ailing nation grieve in a very public and meaningful way. His death — and, in fact, his life — was perhaps best summed up by Charles B. Sedgwick. He gave a eulogy in Syracuse, New York, and said (via the Onondaga Historical Association), "He went at the call of duty to the post of danger, and although wrecked, his life is by no means lost."