What Life Was Really Like For Slaves In America

The anodyne thing to do would be to pretend this article exists in a vacuum, but out of respect for your intelligence as a reader, the moment at hand should be acknowledged. It's probably obvious, given the recent spate of protests and unrest surrounding racism and police brutality, that both cynical tokens of wokeness and heartfelt reflections about race — while always relevant on some level — have become especially topical. One current topic that seems especially relevant to discussing slavery, for reasons that will hopefully become clear, is the removal of Confederate monuments.

The push to pull down Confederate statues has long been a bone of cultural contention, most likely the femur. Now that the movement has legs, it's kicked off old debates that expose inconsistencies in how Americans discuss racism and institutions that have engendered it. For instance, as Time details, in June, Virginia Governor Ralph Northam, of blackface infamy, declared that the state would take down the gigantic Robert E. Lee monument mounted in Richmond, the heart of the former Confederacy. Senator Amanda Chase condemned the move, lamenting, "There's an overt effort to erase all white history."

Ignoring the ironic and perhaps surprising fact that General Lee rejected the idea of erecting such monuments, according to an 1869 publication, because he thought they would "keep open the sores of war," what stands out about Chase's complaint is that some Americans have spent years trying to erase the ugliness of slavery vis-a-vis the Civil War, and more generally.

The whitewashing of slavery

As Smithsonian Magazine recounts, in 2010, the Texas Board of Education revised its curriculum to play up the role of "states' rights" in igniting the Civil War while downplaying the primacy of slavery, calling the latter a "contributing factor." It rescinded this shift in 2018.

For a bit of historical context, Texas's declaration of secession (via the American Battlefield Trust) directly tied its status as a U.S. state with "maintaining and protecting the institution known as negro slavery — the servitude of the African to the white race within her limits — a relation that had existed from the first settlement of her wilderness by the white race, and which her people intended should exist in all future time." It also condemns "the debasing doctrine of equality of all men, irrespective of race or color," calling it "a doctrine at war with nature, in opposition to the experience of mankind, and in violation of the plainest revelations of Divine Law."

That sort of blatant revisionism arguably reflects a broader whitewashing of slavery. Per NPR, in 2015, textbooks at a Houston high school described the Atlantic Slave Trade as "patterns of immigration" that brought "millions of workers from Africa to the southern United States to work on agricultural plantations." This sort of historical gaslighting isn't new. Frederick Douglass's 1845 memoir took aim at the myth that slaves happily sang while toiling in the fields, according the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Setting the broken record straight

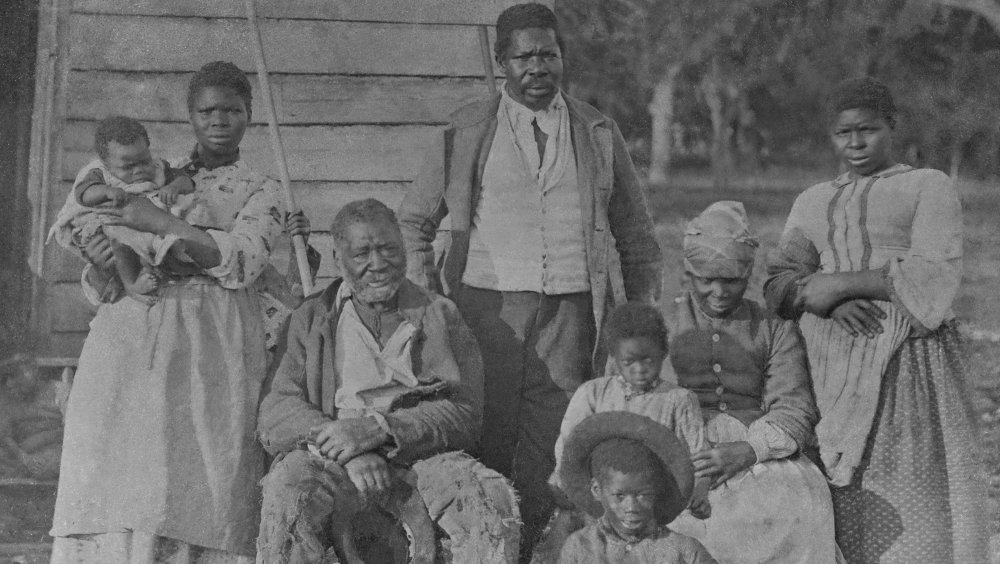

PBS writes that by 1830, slavery was mostly sustained in Southern states, and about 90 percent of slaves lived in rural settings. The specific circumstances varied, but the system operated under the unifying premise that "slaves were considered property, and they were property because they were black." Killing slaves was rarely considered murder, and raping them "was treated as a form of trespassing." The women had no option to say no to their owners, who often used them as sex slaves.

Slaves lived in abysmal conditions, and often died in them. Their quarters left them vulnerable to the elements, and disease. Those who worked in rice fields spent hours standing in water in the blazing heat, and often contracted malaria from mosquitoes.

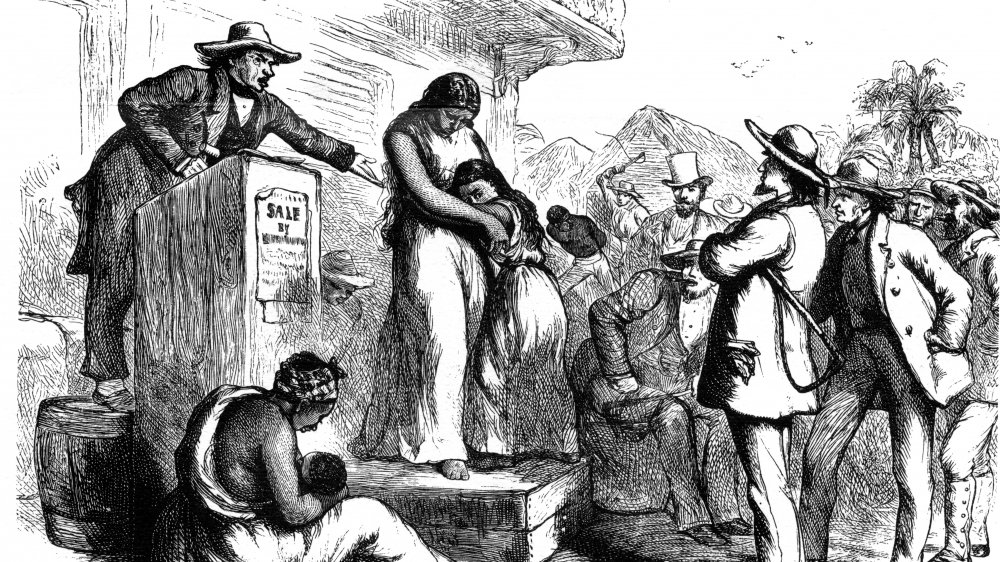

With inadequate nutrition and practically nonexistent care, slaves were left to fight off the illness with little more than power of will. But there was no time to rest. Sick days didn't exist, because slaves weren't workers. The child mortality rate among slaves was 90 percent. Children who survived were often ripped away from their parents and auctioned off. Families were systematically torn apart, often without warning.

Whippings, torture, maiming, and incarcerations were common punishments for slaves who tried to escape, weren't deemed productive enough, or weren't subservient. Some may try to find less awful examples to argue slavery wasn't always so cruel, but this is like citing Stockholm Syndrome in defense of kidnapping. Perhaps that issue will persist until the nation collectively faces the music — and no, that doesn't mean the "happy" singing of slaves.