The Untold Truth Of The First Slaves To Arrive In North America

The year was 1619; the place, Point Comfort, on the coast of what is now Virginia. English colonists engaged in a bit of commerce with some privateers. According to Smithsonian, "20. and odd Negroes" were exchanged for food. The names of the Africans have been lost — not even the exact number is known — but the event is often regarded as the beginning of African slaves in North America.

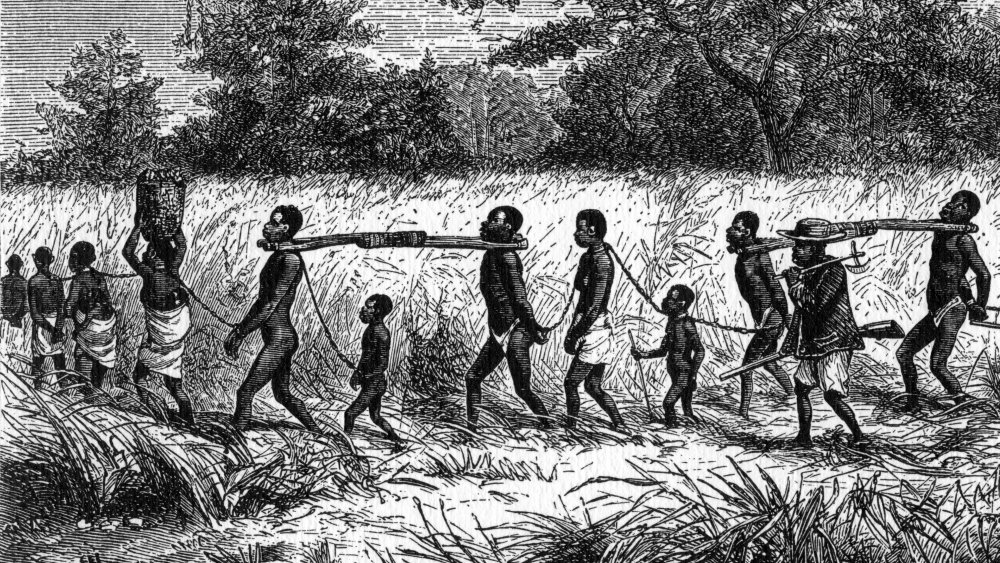

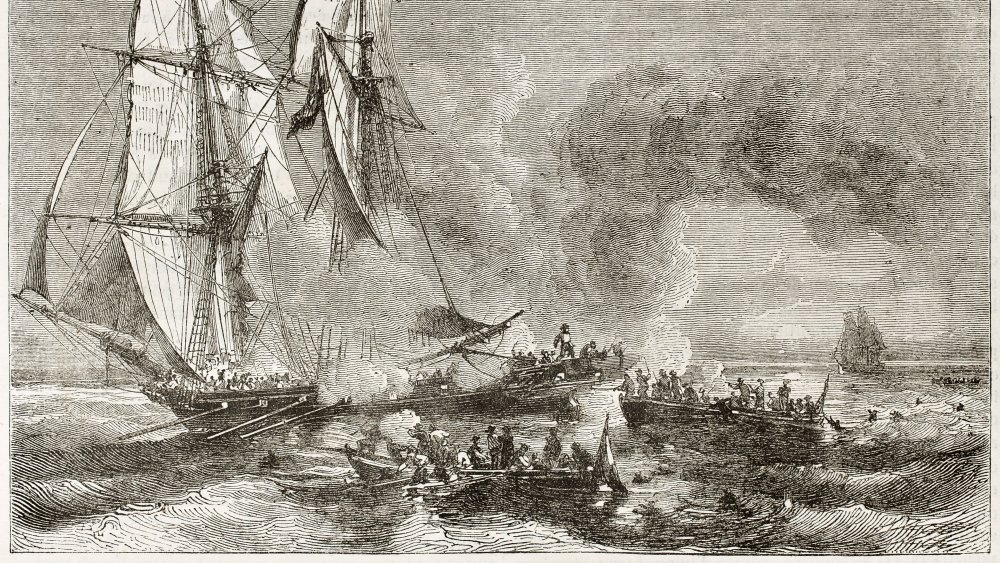

As History relates, a ship making the voyage from Africa — the San Juan Bautista, "St. John the Baptist" — originally had 350 slaves on board, bound for Vera Cruz in the colony of New Spain. About 150 of them died en route; apparently a pretty standard rate of loss for such trips. Further, the ship was attacked by English privateers, who took 60 of the human cargo, and it was one of those two English ships, the White Lion, which struck the deal with the English colonists on August 20.

An outdated story

As Time points out, "something did change in 1619. Because of the central role of the English colonies in American history, the introduction of the transatlantic slave trade to Virginia is likewise central to this ugly and inescapable part of that story."

1619, unfortunately, has become to slavery in America what 1492 is to the discovery of America — a simplified, misleading version of a much more complicated event. Some scholars even contend that the Africans offloaded in Virginia in 1619 weren't actually slaves, but rather entered indentured servitude: working for nothing beyond food and shelter, sometimes to pay a debt, for an agreed-upon period of time. While some of those arriving at Point Comfort did obtain their freedom, the terms of their servitude fit that of enslaved peoples, as delineated by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Regardless, there were many other incidents of Africans coming to North America and shaping its history long before 1619.

History points to a different story

According to Smithsonian, there's evidence of slaves, captured from the Spanish, on Sir Francis Drake's ships that visited Roanoke Island in 1586. Sixty years before, Spaniards brought African slaves with them when they attempted a colony in what's now South Carolina. "Those Africans launched a rebellion in November of that year and effectively destroyed the Spanish settlers' ability to sustain the settlement," writes Smithsonian, "which they abandoned a year later. Nearly 100 years before Jamestown, African actors enabled American colonies to survive, and they were equally able to destroy European colonial ventures."

Time says that Spaniards brought other slaves with them to present-day St. Augustine, Florida, in 1565 — the first European settlement in what's now the continental United States — and that the first documented black person to arrive in what would become the U.S. was Juan Garrido, who accompanied Juan Ponce de León in search of the Fountain of Youth in 1513.

Slavery's true beginning

The problem with treating 1619 as "the beginning of slavery in America" is that it simply doesn't tell the whole, multinational story of our country's origin. Smithsonian notes that is that it disregards an estimated "500,000 African men, women, and children who had already crossed the Atlantic against their will, aided and abetted Europeans in their endeavors, provided expertise and guidance in a range of enterprises, suffered, died, and – most importantly – endured."

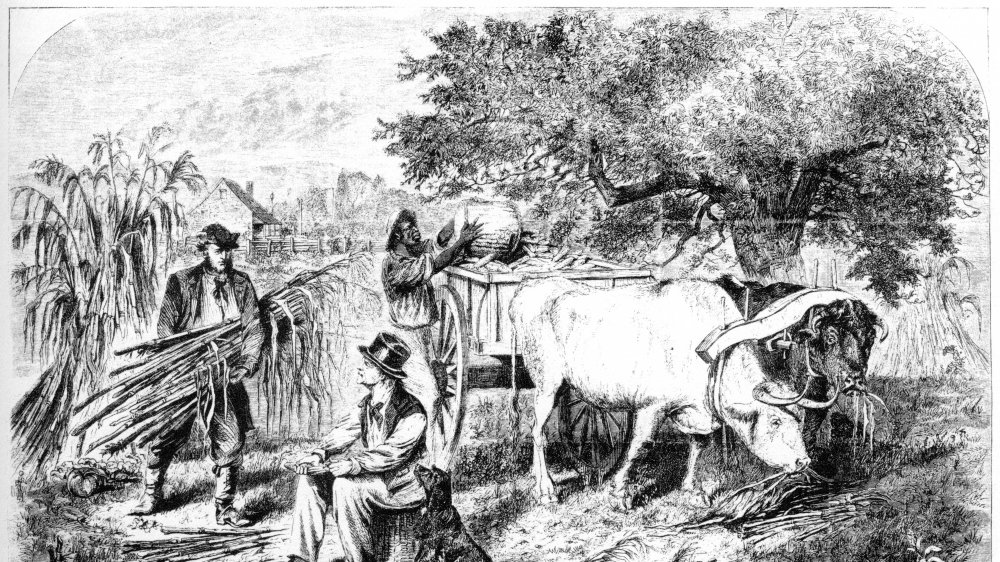

African slaves made contributions ranging "from vocabulary to agriculture to cuisine, including staples like rice that were a key part of the English colonies' success. They probably also brought some Christian practices that they learned from the Portuguese Catholic missionaries in Africa."

The story we've been told is a one-dimensional, whitewashed version that disregards contributions from blacks, Hispanics and indigenous peoples. The simplified version makes it easy to gloss over centuries of struggle — and triumph in the face of adversity — that characterize the experience of minorities in America.

Finding the truth

"People don't tend to want to think about early U.S. history as being anything but English and English-speaking," Michael Guasco, historian at Davidson College and author of Slaves and Englishmen: Human Bondage in the Early Modern Atlantic World, told Time. "There is a Hispanic heritage that predates the U.S, and there's a tendency for people to willingly forget or omit the early history of Florida, Texas and California, particularly as the politics of today want to push back against Spanish language and immigration from Latin America."

Focusing on the specifics of an event that took place almost 400 years ago might seem irrelevant, but by understanding the foundational story of black history and the history of slavery in North America in its proper context, we gain valuable perspective for the present, and can better shape our future. Working to solve issues of race and inequality starts with acknowledgement of the past. The good, the bad and the ugly.

From there, we can begin to heal, and to move beyond a narrative of "before and after"; "us and them."