The Crazy Real-Life Story Of Frederick Douglass

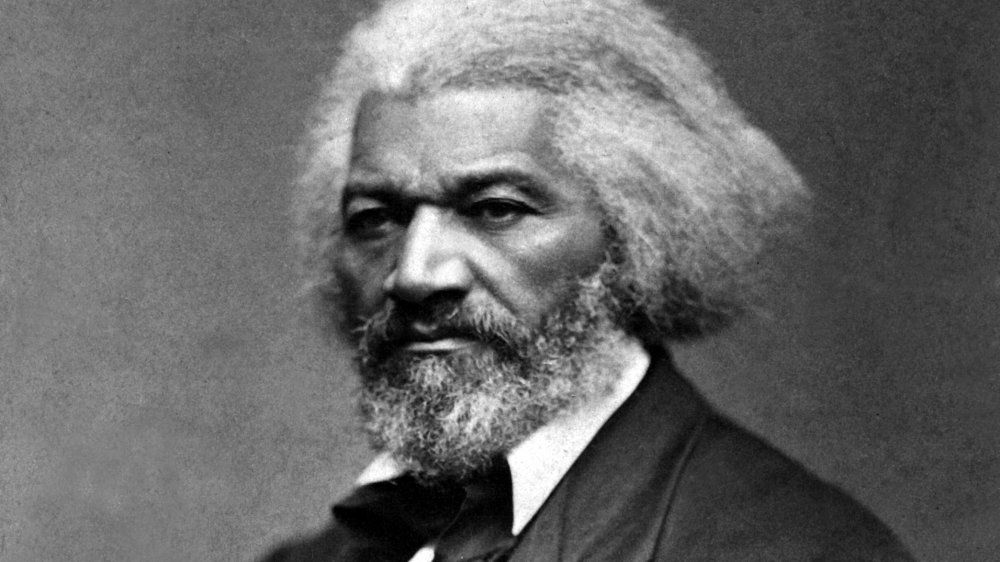

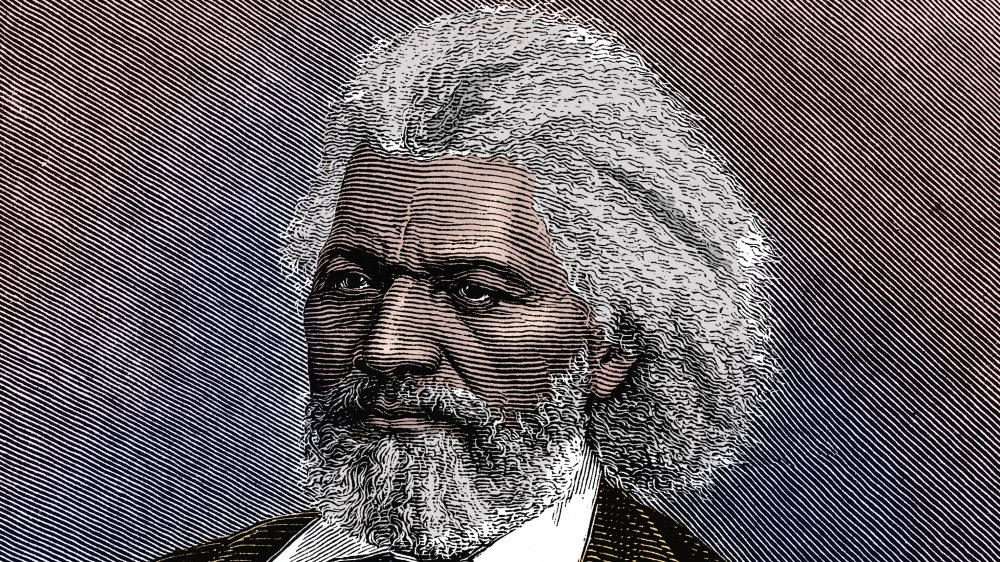

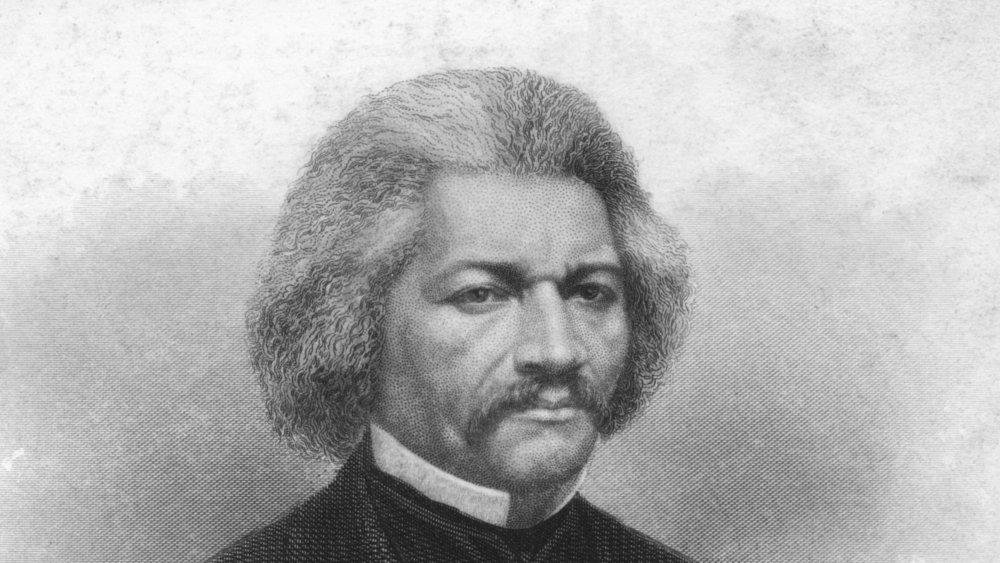

The most photographed man in the 19th century was not a king or an elected world leader. He was a man who spent the first 20 years of his life enslaved, but always yearning for freedom.

After escaping from slavery in 1838, Frederick Douglass became one of the most famous abolitionists in the US. He stirred audiences to join the cause of ending slavery through speeches that were so fiery and articulate that condescending white spectators questioned whether he had really been a slave. To shut them up and spread his message further, Douglass published three autobiographies: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845), My Bondage and My Freedom (1855) and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1892). He also established his own newspaper, The North Star, to encourage black people to write and publish their own stories, instead of relying on white-owned publications like William Lloyd Garrison's The Liberator.

Over the course of his remarkable life, Douglass went from slave to self-taught intellectual and abolitionist hero to serving as a diplomat under multiple presidents. Even after slavery was abolished, he continued to work in the name of now-freed black people, campaigning against lynching and for suffrage. This is the crazy real-life story of Frederick Douglass, the man who refused to let one of the cruelest institutions in American history break his spirit — and who fought to rescue others from its grip.

Slavery divided Frederick Douglass' family

Douglass was born in Tuckahoe, which he described in My Bondage and My Freedom as a "singularly unpromising and truly famine stricken district" in Talbot County, Maryland. Many slaveholders didn't bother to record the family histories of enslaved people, and not being able to read, write, or count months made it hard for the people themselves to keep careful records. As such, Douglass never knew his exact birthdate: He estimated it was in February 1817 or 1818 and later chose to celebrate his birthday on Valentine's Day, February 14.

Douglass never knew who his father was, just that he was probably white and was rumored to be Captain Anthony, the slaveholder who had enslaved Douglass' mother. For the first seven or so years of his life, Douglass was raised by his maternal grandparents, Betsey and Isaac Bailey. Although Isaac was free, Betsey was an enslaved woman and was well-respected in the region for her nursing, fishing, and gardening skills, as well as for looking after children whose parents had been sent away.

Douglass' mother Harriet was one such person. She had been "hired out," sent by Anthony to work for another farmer 12 miles away. When possible, she would walk to visit Douglass, but she had to be home in time for roll call in the fields. Douglass only saw her a few times in his life and mostly remembered the way she looked: He wrote in Life and Times that she was tall, dark-skinned, and dignified.

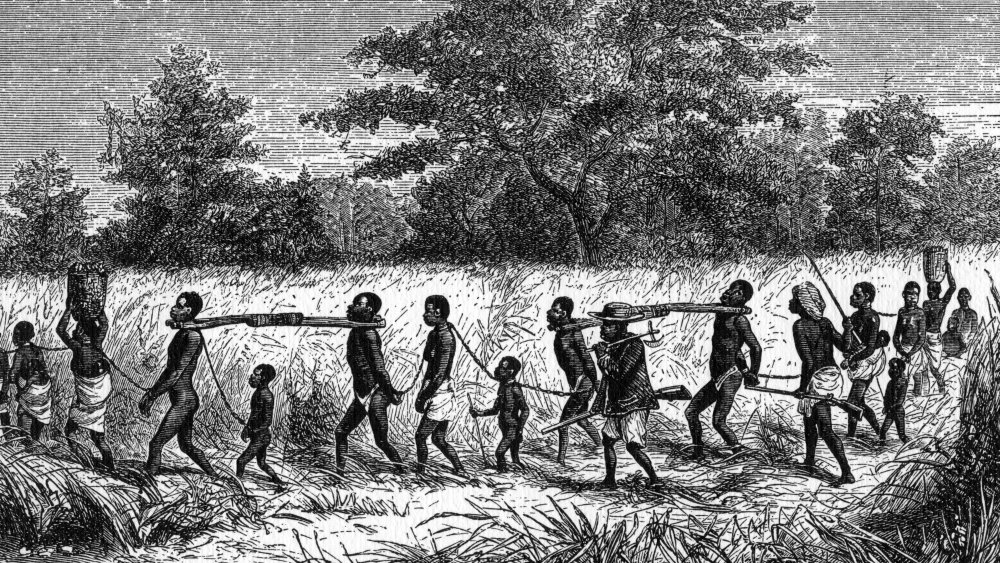

Frederick Douglass witnessed the brutalities of slavery from a very young age

Douglass credits his grandmother Betsey with shielding him from slavery when he was a small child — both from witnessing it and understanding that he was legally enslaved. "I knew many other things before I knew that," he wrote in My Bondage. They lived in a simple wooden cabin, which Douglass loved, away from the main plantation. But when Douglass was around seven, Betsey was forced to take him to join the other enslaved people working on the estate.

This was the first time Douglass learned what it meant to be enslaved. With the rest of the children, he was put in the "care" of an enslaved woman named Aunt Katy, who starved and beat her charges. Douglass remembered that he would compete with the dog for crumbs from the floor. The enslaved people were given barely any clothes to keep them warm or covered, and the children weren't even given a blanket to sleep under.

In addition to this abuse, it was at the plantation that Douglass first witnessed the horrifying violence perpetuated by slaveholders and overseers. One morning, he stumbled across Captain Anthony whipping Esther, Douglass' aunt, because he was jealous of her relationship with an enslaved man, Edward. He also heard that an overseer named Gore had shot an enslaved man, Denby, in the face for refusing to be whipped. As Douglass pointed out, these were just two examples of the constant violence legalized under slavery.

Frederick Douglass was determined to learn to read

When Frederick Douglass was around nine years old, he was sent to live in Baltimore with Hugh and Sophia Auld and their young son Tommy. Hugh was the brother of Thomas Auld, Captain Anthony's brother-in-law. At first, Douglass was treated much better. Sophia had never been a slaveholder, and she naturally saw Douglass as a child rather than a piece of property. Unlike under Anthony's watch, Douglass was given enough to eat and a comfortable place to sleep. Sophia also started to teach him to read, until her husband stopped her, telling her that teaching an enslaved person to read would give them ideas about freedom.

After that, Sophia became markedly crueler, but Hugh's words only gave Douglass even more reason to keep learning. He convinced the white boys he befriended while running errands to teach him to read and write. After Tommy started attending school, Douglass would borrow the lesson books he left lying around the house and carefully copy the letters.

Being able to read allowed Douglass to access books and newspapers that criticized the inhumanity of slavery, confirming what he'd known innately since he was a child. When he was sent back to Talbot County, he started multiple Sunday schools to teach fellow enslaved people to read and write, and he continued to teach free people after he escaped.

Frederick Douglass had a complicated relationship with religion

While living in Baltimore and reading more about slavery, Douglass became depressed, thinking that he would never be free. He turned to Charles Lawson, a black man who lived nearby, who taught him about Christianity and how to pray, while Douglass helped him improve his reading in return. "He was my spiritual father and I loved him intensely [...] He fanned my already intense love of knowledge into a flame by assuring me that I was to be a useful man in the world," Douglass wrote in Life and Times. When Hugh Auld banned him from meeting Lawson, it only further motivated Douglass to escape one day.

However, throughout his life, Douglass also hated the hypocrisy he witnessed among those who claimed to worship the same God he did while also enslaving people. He was also suspicious of the racist practices he witnessed in Northern churches. Two of the most violent and abusive men he encountered — Thomas Auld and Edward Covey — were both known to their white peers as pious churchgoers. Many Christians used the Bible to justify slavery and taught the people they enslaved that this was what God wanted and that if they tolerated slavery during their lifetime, they would be rewarded in heaven. Douglass argued that God was good, and therefore he could not have ordained slavery. His faith wavered in his darkest moments, but he ultimately maintained his belief in a just God throughout his life.

Frederick Douglass was sent to be broken

In 1833, when Douglass was around 15 or 16, he was sent south from Baltimore to St. Michael's in Talbot County to live with Thomas Auld. Auld had "inherited" Douglass after Captain Anthony and his daughter — Douglass' previous legal holders — had died. Auld starved and beat the enslaved people on his farm and threatened to kill Douglass for starting a Sunday school.

By this time, Douglass was in full internal mutiny against slavery, and he resisted Auld's abuse. Auld sent him to live with "slave breaker" Edward Covey for a year. Covey forced Douglass to work to the point of exhaustion, with minimal sleep or opportunity to eat, and beat him violently. "Mr. Covey succeeded in breaking me — in body, soul, and spirit [...] my intellect languished; the disposition to read departed [...] the dark night of slavery closed in upon me, and behold a man transformed to a brute!" Douglass wrote in Life and Times.

After one violent incident, Douglass decided he would fight back. When Covey tried to beat him again, Douglass overpowered him, and after a couple of hours, Covey gave up. He never laid a hand on Douglass again. This was a pivotal moment for Douglass. "After resisting him, I felt as I had never felt before. It was a resurrection from the dark and pestiferous tomb of slavery, to the heaven of comparative freedom," he wrote in Life and Times.

Frederick Douglass planned to escape slavery from childhood

Douglass wrote in Life and Times that many enslaved people were so broken by slavery that they lost the will to escape and became resigned to their condition — but he never did. From the time he was a child, he understood that slavery was wrong and yearned to be free.

It wasn't only under cruel slaveholders that Douglass resented being enslaved: He knew that the entire principle of one human owning another was wrong, regardless of how generous the holder was. While he lived with Covey, he was too dispirited to try to escape. But when he was sent to live with the comparatively kind William Freeland in 1835, Douglass was able to recover physically and mentally enough to launch his first escape attempt.

In 1836, when he was 18 or 19, Douglass and five other men planned to paddle a canoe 70 miles from St. Michael's on the southeast of Maryland to just north of Baltimore in the northwest. If that sounds incredibly dangerous, you're right. But Douglass and his conspirators never even got the chance to try. One of the men betrayed the group, and the other five were arrested and jailed. Thomas Auld showed up and threatened to send Douglass to the Deep South, which would have made escape much more difficult. But for some reason, he ultimately sent Douglass back to his brother Hugh Auld in Baltimore — unwittingly giving him the chance to try again.

Frederick Douglass refused to reveal how he escaped for years

In his first two autobiographies, Douglass refused to reveal how he finally escaped. He worried other enslaved people were more likely to be caught if he gave slave catchers a manual on their escape methods. However, in Life and Times – published after slavery had legally ended — he finally revealed his smart and daring plan. While in Baltimore, Douglass learned to caulk (to waterproof ships) and became friends with some free black sailors. He managed to save up a small amount of money from hiring out his time, and he may have also had financial help from his new fiancée, Anna Murray, a free black woman.

In 1838, one of Douglass' friends lent him sailor's papers: documents that certified that he was a free sailor and therefore allowed to travel. According to Smithsonian Magazine, Murray sewed Douglass a sailor's outfit, and he boarded a train to Philadelphia. He had to take several trains and boats to reach the North, persuading train conductors and nosy passengers that he was a free man. At one point, he saw someone he knew and was sure he was recognized — but the man chose not to turn him in.

After reaching Philadelphia, Douglass carried on to New York, arriving on September 3. "I had [...] been dragging a heavy chain which no strength of mine could break [...] my chains were broken, and the victory brought me unspeakable joy," Douglass wrote in Life and Times.

Freedom wasn't all easy

Although Douglass was ecstatic to be free, his first few weeks in New York were tough. Maybe one of the lies you learned in history class was that the Northern states were a haven for black people. On the contrary, Douglass was under constant threat of being kidnapped by slave catchers — or even free black people they'd hired — and dragged back to Thomas Auld or sold to someone else. An acquaintance he ran into who was also on the run warned him not to go to the wharves or any black boarding houses, since these were the first places people would look for him.

Fortunately, one night Douglass met a sailor who took him to the house of famed New York abolitionist David Ruggles. Ruggles not only let Douglass stay with him, but he helped him make plans to move to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he might be able to find work caulking whaling ships and where the local community — black and white — would protect him from slave catchers. He also married Douglass and Anna Murray.

Racism at the New Bedford shipyards meant Douglass struggled to find work caulking, and he spent the first three years in New Bedford working hard manual labor while Anna worked in domestic service. But it was still freedom. "The consciousness that I was free — no longer a slave — kept me cheerful under this and many similar proscriptions which I was destined to meet in New Bedford," Douglass wrote in Life and Times.

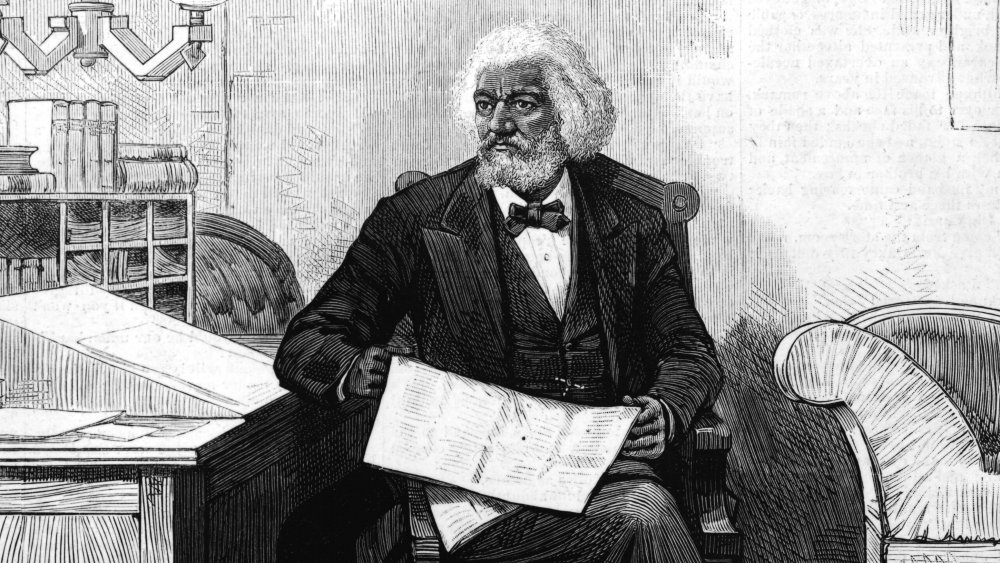

Frederick Douglass became a force in the abolitionist movement

Douglass is most famous today is thanks to his work in the abolitionist movement. He first heard about abolitionists while he was enslaved in Baltimore, but it was when he moved to New Bedford that he was able to participate for the first time. He subscribed to William Lloyd Garrison's abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, and attended anti-slavery lectures in the city.

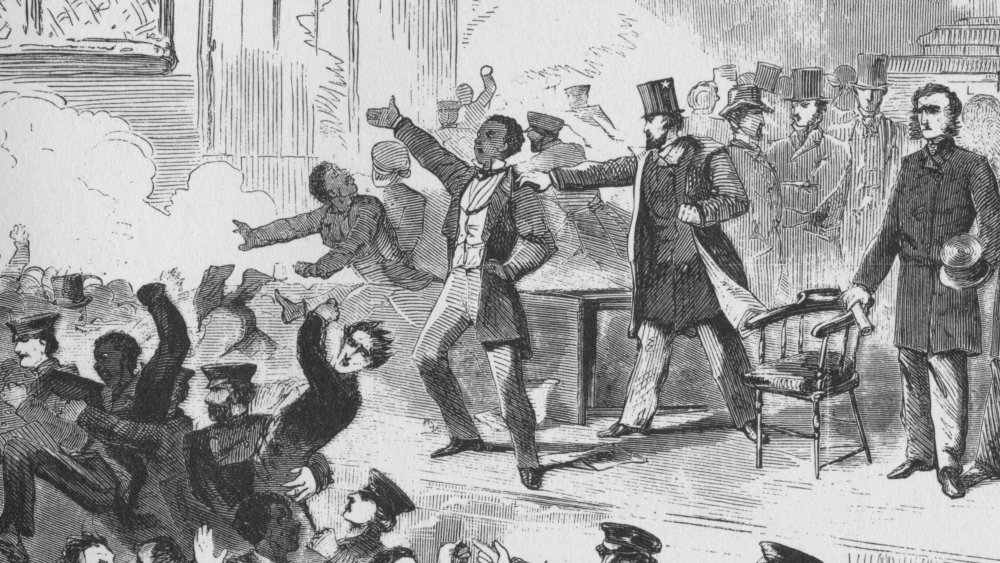

In 1841, Garrison hosted a convention in Nantucket, and abolitionist William C. Coffin encouraged Douglass to speak about his experiences. Douglass felt the speech didn't go very well, but it made enough of an impact that he was recruited to join the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. Douglass traveled around the country, lecturing on the evils of slavery. He was so articulate that some white audience members didn't believe he'd been enslaved. Douglass wrote the first of his autobiographies, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, to back up his story.

Speaking out in public put Douglass in considerable danger of being kidnapped and taken back to Auld. When Narrative of the Life became a bestseller, the risk was so great that he moved to England, where he traveled around lecturing on American slavery. While he was there, without asking his permission, some of his friends combined their money and bought his freedom. Although some of his other friends viewed this as an endorsement of slavery, Douglass was grateful, describing it in My Bondage as a ransom.

Frederick Douglass' second marriage caused scandal

Douglass was married to Anna Murray for 44 years, until she died aged 69 in 1882. According to Smithsonian Magazine, Murray looked after their five children by herself while Douglass traveled, supporting them by mending shoes. Murray never learned to read or write, and she felt that she didn't fit in with Douglass' set of intellectuals. However, she still worked alongside her husband in the abolition movement. At their house, Murray hosted enslaved people on the run as part of the Underground Railroad, as well as various abolitionists, including women Douglass was accused of having affairs with. The couple also suffered the death of one child, and in 1872, their house in Rochester, New York, was burned down. (Thankfully, no one was hurt.)

In 1855, Douglass met white German journalist Ottilie Assing, and the two supposedly continued an affair by letter until she committed suicide in August 1884. Some blamed Douglass for Assing's death: In January 1884, he'd remarried another woman, Helen Pitts, a New York-born abolitionist 20 years his junior. But it wasn't her age that was most scandalous at the time — it was the fact she was white. Her parents, though abolitionists, both disowned her, and Douglass' children and some former friends opposed the relationship, seeing it as a betrayal of Murray and of black women in general. After Douglass died in 1895, Pitts raised funds to turn his estate into a memorial and even convinced Congress to pass a bill establishing the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association.

Frederick Douglass was a self-proclaimed women's rights man

Black and white women were leaders in the abolition movement. Hopefully you've heard of Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman, but other black women who risked their lives for the freedom of enslaved people include Harriet Jacobs (who wrote her own narrative), Charlotte Forten Grimké, and Ellen Craft, to name just three. White women who campaigned to end slavery include Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, now famous for their women's suffrage campaigns.

Meeting many brilliant women inspired Douglass to support women's rights — though he was one of just a few men to do so. In Life and Times, he wrote that he had been, "denominated a woman's-rights man. I am glad to say that I have never been ashamed to be thus designated," adding, "there was no foundation in reason or justice for woman's exclusion from the right of choice in the selection of the persons who should frame the laws."

However, after slavery was abolished, Douglass and the feminists diverged over what to do next, according to the Social Welfare History Project. Stanton and Anthony wanted to work on achieving suffrage for women and black men at the same time, whereas Douglass felt black men more deserved their focus. Despite this disagreement, he continued to champion women. The last speech Douglass gave — just hours before he died, on February 20, 1895 – was at a meeting of the National Council of Women.