The Messed Up Reality About The Railroad Industry

The railroad's impact on American history can't be overstated. Though the United States stretched from coast to coast before the Civil War, the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 made traversing such vast terrain seem achievable in a way not possible before. By the nation's centennial seven years later, the rail system could take a passenger across the country in just one week. And the greater ease of travel helped shift the mindset of citizens in the post-war era. Where the U.S. was often thought of as a loose collection of states before, it was now more widely seen and embraced as a unified country.

But if the railroad played its part in uniting the states and advancing the settlement of the west, it didn't maintain pride of place among transportation systems. Unlike Japan, China, and many European nations, the U.S. began to neglect rail over the 20th century in favor of the automobile. Increased access to air travel made it an appealing option over the train too. Today, American passenger rail suffers badly in comparison to peer nations.

The freight rail industry has enjoyed more success by comparison. Its cost-effectiveness and safety profile compared to other means of shifting are often touted. But increasing strife among workers and a series of accidents in recent years, like the chemical spill in Ohio in February 2023 (per AP), have brought that reputation into question.

Railroads were some of the most powerful and destructive monopolies of the Gilded Age

The term "gilded age" was borrowed from a satirical novel by Mark Twain. In the years following the Civil War, the United States saw a massive generation of wealth, much of it unevenly distributed among a select few industrialists, bankers, and politicians of loose ethics. The ripple effects of industrialization allowed a class of robber barons to exercise power that often eclipsed that of the elected statesmen they rubbed elbows with. And among the most powerful of these businessmen were the railway tycoons.

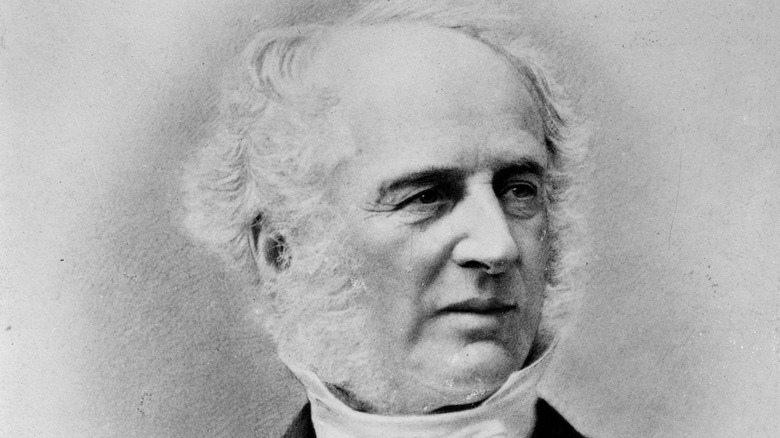

Men like Cornelius Vanderbilt amassed great fortunes through their control over railways. Government oversight was minimal; corrupt politicians were more likely to increase the barons' wealth and holdings after cutting deals. Monopolies over select routes let these businessmen charge whatever they wanted. This effectively froze the poor out of train travel, and it left farmers at the mercy of the rail companies who could get their wares quickly to market.

Monopolies were maintained through government corruption, cooperation among rival companies to divide up business, and freezing out the competition. Wealth was concentrated among the barons partially by meager wages paid out to workers. Resentful employees took to the picket line more than once. A series of eight strikes between 1876 and 1877 disrupted shipping throughout America and culminated in widespread violence (per History). But the rail monopolies, and the Gilded Age, endured into the early 20th century.

Rail construction led to massive deforestation (but would reduce greenhouse gasses)

One of the consequences of the massive expansion of railroads in the late 19th century was massive deforestation. Rail as an industry demanded timber for ties, fuel for the locomotives, support beams for bridges and tunnels, and lodging and heat for the workers needed to build railways. Tracks built in haste needed repairs. And just by being able to deliver large numbers of people to previously remote locations, the railroad accelerated the settlement of the west and the accompanying sacrifice of forests to towns and mines.

For all its negative environmental effects in the past, rail these days is often pointed to as an environmental savior. In 2019, the International Energy Agency said (via CarbonBrief) that a concerted push to expand rail could cause greenhouse gas emissions to peak by 2030. Of all transportation options, rail was furthest along in electrification and had one of the lowest carbon footprints.

The United States has significantly less high-speed rail than its peer nations; only one line, servicing the Northeast, even qualifies for the title. A concerted push by auto and oil companies after World War II convinced the federal government to prioritize the highway system over rail, a shift in transportation thinking that has yet to break. Efforts by individual states to build high-speed rail have run into regulatory and financial issues. The size of the United States, and the vast variety of terrain, is another complicating factor.

Deregulation improved performance but hurt the overall system

The power of railroad tycoons was curbed over the first half of the 20th century. The New Deal gave the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), the regulatory body overseeing railways, teeth. But regulations often failed to account for changes in technology, travel habits, and limited room for expansion. By 1970, smaller lines had largely disappeared, and major railroad companies were facing bankruptcy.

The proposed answer to this decline was deregulation. In 1980, Congress passed the Staggers Rail Act. Among other changes, it lifted the requirement that the ICC approve rate changes, let rail companies close unprofitable lines more easily, and permitted more mergers between firms. The results, the Association of American Railroads argued in The Washington Post, were an unqualified success. In the decades following Staggers, the productivity of freight rail shot up, to the point that one-third of U.S. exports were carried by train, while shipping rates dramatically declined.

But the AAP's favored interpretation of the data may not tell the whole story. With mergers and consolidations made easier, the number of Class 1 (long-haul) railroads has plummeted since Staggers. The just-in-time operating model favored by the industry helps stock prices and dividends but at the expense of basic maintenance and service necessities. And reducing the number of railroads, and rail workers, has left the system with little flexibility in the event of a crisis.

Amtrak can't turn a profit

The name most associated with the modern American rail system is Amtrak. Officially named the National Railroad Passenger Corporation, Amtrak has been responsible for nearly every passenger railroad in the United States since 1970. The way it works is that Amtrak operates passenger rail lines, pays railroads to use their tracks, and shoulders maintenance and upgrade costs.

Amtrak saw a steady rise in passengers from 2000 up until the pandemic, but the corporation has always operated with difficulty. By design, it was meant to be self-sustaining, with passenger tickets and postal services providing revenue. Operating costs, however, routinely exceeded income, necessitating federal and state subsidies that have sometimes been restricted. In part, Amtrak's costs come from its requirement to maintain long-distance lines that lose money. Against any financial issues, passengers of lines like the Empire Builder, which connects Chicago to the Pacific Northwest, value the service. And Senator Maria Cantwell of Washington state has argued that such long-distance trains offer an alternative to driving that lets Americans take in the beauty of the country (per The Spokesman-Review).

But that still leaves Amtrak operating at a loss. It's never turned a profit, and arguably can't under the current model. Funding has long been just enough to maintain aging lines and equipment. The Biden administration pushed to increase Amtrak's budget, but experts said even their $80 billion target would need to grow to get America's passenger trains up to the standard of peer nations.

American freight rail is far ahead of passenger rail

The United States passenger rail system has seen a sharp decline in its standing relative to other nations. From having the finest such system at the turn of the 20th century, China now uses U.S. passenger rail as a negative example compared to their own claimed ingenuity and efficiency. But neither China nor any other nation has surpassed America in freight rail.

According to CNBC, the freight rail industry was responsible for transporting a third of U.S. exports in 2022. Across over 100,000 miles of track over 49 states, it's among the most efficient ways to move fuel, cars, and an increasingly large number of consumer products, and the seven companies that command most of the market share set world records for rail profits. Rail executives have attributed this, in part, to freight rail's privatized nature in the U.S. compared to other countries, where the railways are nationalized.

But freight rail, like other industries involved in supply chains, suffered in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Even before then, problems were mounting. Poor service from rail companies, and a degree of control sometimes called monopolistic, have driven some shippers towards trucks. And ongoing work shortages, even at individual stations, have nationwide effects on performance not seen in other industries connected to supply chains.

Staffing is an ongoing issue for freight rail

Throughout 2022, there were concerns that the American supply chain would be jeopardized by a freight rail strike. Over the objections of unions representing railway workers, rail companies had made dramatic staff cuts since 2017, while increasing the length of operating trains and adopting inflexible business models. While railroads insisted that such changes didn't represent a threat to safety, rail unions maintained that with fewer staff, a serious accident was only a matter of time.

Other tensions besides layoffs drove rail workers to consider striking. Conditions for remaining workers, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, had grown increasingly strenuous. As negotiations for a new union contract began in the winter of 2021, a major sticking point became paid sick leave. Rail workers are not guaranteed sick leave, according to New York Magazine, and must use vacation time that requires several days' notice before approval. Rail companies thought granting sick leave jeopardized their just-in-time operating model and refused to grant more than one paid sick day.

A rail strike could cost the American economy up to $2 billion a day. The Biden administration became personally involved in the negotiations between companies and unions. The agreement reached still didn't have sick leave provisions, and several unions involved still planned to strike. But legislation by Congress and signed by President Joe Biden in December 2022 imposed the agreement on railroads and workers (per USA Today).

Tensions between freight rail and its customers have been growing for years

If profits for U.S. freight rail have been the highest in the world in recent years, the industry's reputation with its customers is another story. As rail service returned to normal after the COVID-19 pandemic and prolonged union negotiations in 2022, a chemical executive whose firm depended on rail told CNN Business, "It's important to note ... that 'normal service' is still incredibly bad and increasingly expensive for shippers and consumers."

Rail service can regularly see delays of over three days, and many shippers dependent on rail services only have a single company they can work with. This means that they have no opportunity to negotiate for better rates. Professor Pete Swan told CNN Business that the railroads likely wouldn't be able to stay in business with such poor performance if they didn't exert a near monopoly on key shipping routes.

Trucks provide an alternative to trains, and many customers prefer to use trucks to transport their goods. They're more reliably on time and their parent companies provide better tracking of shipments. But trucking can't match rail for volume. As service issues have persisted and grown, calls for federal regulation and stricter penalties have gotten louder, sometimes from other businesses tired of dealing with the railroads.

The Ohio train derailment of February 2023 wasn't the first

On February 3, 2023, a freight train operated by Norfolk Southern derailed near the town of East Palestine, Ohio. 50 cars came off the tracks, according to Chemical & Engineering News. Among those 50 were five cars loaded with vinyl chloride, a carcinogenic chemical that releases the poisonous gas phosgene when burned. Evacuation orders were issued for the nearby area as authorities oversaw a controlled burn starting February 6.

The accident made national headlines, but it wasn't the first in recent years. The state of Ohio had seen two other derailments in the four months before the East Palestine incident. 20 cars carrying paraffin derailed in October 2022. The spilled material caused damage to roads and sewers that were still being cleaned months later. And 15 cars carrying garbage were lost the following month, spilling their contents into the Ohio River (per The Times Leader).

Nor have train accidents been confined to Ohio. On December 30, 2013, two trains operated by BNFS Railway collided in North Dakota. Per USA Today, the train hauling grain had already derailed when another, loaded with oil and coming from the other direction, struck the grain car. 18 of the oil cars were breached, leading to an explosion that burned up almost 500,000 gallons of oil and cost $7.2 million. Fortunately, there were no casualties.

Efforts to improve train safety were watered down by lobbyists and repealed

Rail is generally considered a safe way to move cargo. But safety concerns have grown as staff has been reduced and upgrades neglected. After an accident in North Dakota spilled thousands of gallons of oil in 2013, and another in Quebec killed 47 people, the Obama administration began pursuing new regulations for U.S. rail. A proposal was submitted in August 2014 by the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) that targeted trains hauling flammable materials, particularly liquids.

The rules were finalized the following year. Per Reuters, the regulations included new standards for tank cars and rail brakes, and mandated that two-man crews with proper qualifications inspect safety equipment on any parked train hauling crude oil. But these rules were only enacted after a considerable effort was spent by industry lobbyists to stop them, and represented a scaling back of initial proposals; initially, other hazardous materials were to be regulated as well.

A 2016 provision by Congress required that the PHMSA analyze the proposal to replace the brakes on trains hauling hazardous materials and to repeal them if the benefits were less than the costs (per The Hill). The following year, the Trump administration claimed exactly that, and the measures were abandoned. Even if they had been retained, the exemptions carved out of the regulations meant it wouldn't have applied to the train that derailed in Ohio in February 2023.

Are accidents like Ohio's becoming more common?

There were no casualties in the February 2023 Ohio train accident. Federal and state authorities, and the Norfolk Southern Railway, moved relatively quickly to burn off spilled hazardous chemicals and test the air and water quality of the surrounding area afterward. But some residents forced to evacuate didn't want to return until independent tests could be done. And the high profile of the accident in national news invited questions about the safety of transporting such materials by train.

Accidents on the scale seen in Ohio are rare occurrences. But railroads have long campaigned against increased safety regulations, arguing that the costs would be prohibitive. Braking systems are largely as they were in the days following the Civil War thanks to industry lobbying, and Norfolk Southern was among the companies engaged in that lobbying (per The Lever). Critics of the industry have argued that a business model that loads more cargo onto fewer, longer trains, also poses an increased risk of accidents.

Federal regulations don't stipulate a minimum time for safety inspections of trains. According to USA Today, the average time spent investigating safety has fallen to around 45 seconds in recent years. And while the reduced number of trains on tracks can make the overall accident rate seem low, a look into the numbers by cars damaged or accidents per million miles paints a different picture. Reductions in the workforce have meant fewer human actors are on-hand to respond to such incidents.