11 Of The Strangest Monsters In Roman Mythology

While ancient Rome grew to have one of the longest-lasting and biggest empires in world history, the far-flung corners of its domain remained mysterious to many people. In the absence of first-hand knowledge, folk tales of strange monsters began to circulate. These included deadly snakes, fire-breathing giants, and a decidedly odd take on the unicorn.

Some overlap is inevitable, as the Romans borrowed pretty heavily from Greek mythology and folklore. That's due in part to significant Greek presence in the Roman-held Mediterranean and Rome's openness to incorporating new religious beliefs — not to mention the urge to retell a great monster story.

The greatest source of Roman monster tales is likely Pliny the Elder. Besides being an author, Pliny was a Roman military officer and government official who died while investigating the ongoing eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79. Before he died at the hands of a volcano, Pliny assembled "Natural History," a compendium of the best scientific observations and theories of his day. Yet, while he deserves credit for putting together one of the first encyclopedias in human history, Pliny didn't bother to confirm all of his sources. This means that, for centuries, uncritical readers could turn to his work for tales of shocking, dangerous monsters that were more myth than reality. At the very least, Pliny's monster tales didn't stand alone. Other ancient writers, like the poets Ovid and Lucan, also gave voice to the oddest creatures that stalked the Roman imagination.

Basilisk

If you were to approach a modern-day biologist and ask about the basilisk, you'll likely get a rundown of the tropical lizards that go by that name. And while that may make a herpetologist's heart sing, these lizards — which are admittedly pretty cool, with crests on their heads and the ability to run on top of the water under the right conditions — aren't quite what the Romans had in mind.

For Romans who read Pliny the Elder's "Natural History," the basilisk detailed inside was a frightening monster. He describes it as a serpent that somehow moves upright by locomoting with the middle section of its body. It's frightfully dangerous, in large part because it exudes a vapor so poisonous that anything it touches or even breathes on burns. Pliny notes that it's easy to figure out where the basilisk lives, as it's surrounded by a devastated landscape. Roman poet Lucan makes similar claims in his epic work, the "Pharsalia."

Anyone who attempts to kill the basilisk is pretty much doomed, Pliny writes, as the monster's poison would flow up a weapon and kill the wielder. Sitting high up on a horse wouldn't lend a helpful distance, and the would-be basilisk slayer would end up with a dead horse besides. The only creature believed to be able to defeat the basilisk (albeit in a battle that ensured death all around) was a weasel. The seemingly humble predator isn't just tenacious but was said to emit a miasma that acted as an antidote to the basilisk's mega-poison.

Monoceros

Today, we're all but deluged with sugary-sweet takes on the unicorn, from glitter-encrusted children's clothes to coffee-chain drinks laden with sweeteners and food dye. But, to the Romans and other people of the ancient world, the mighty unicorn was a monster to be feared. Ancient Roman children probably weren't going all starry-eyed over this particular creature.

Pliny refers to this animal as the monoceros and says that it has the thick, stumpy feet of an elephant, a boar's tail, and the body of a horse. Its head, said to be shaped like a deer's, sports a single large, black horn. No delicate whinnies emanate from this creature, either. Instead, Pliny writes that it makes a low-pitched noise. It's also apparently so aggressive — or at least so desperate not to find itself in human hands — that no one's managed to catch it alive.

Writing about a century after Pliny, the Greek Aelian either got more information about the monoceros or thought the earlier Roman's account could use some extra detail. He said that the unicorn had a white body but a purple head. (Earlier tales maintained it had a red noggin.) That came along with a tri-colored horn that was white, black, and then bright red at the tip. If anyone managed to wrangle the unfortunate monoceros and turn its horn into a drinking vessel, it was said that those who drank from it would be free from poisoning or seizures for the rest of their lives.

Onocentaur

You may think you have the concept of the centaur down. It's a creature with the body of a horse, only with a human upper half sprouting from the front shoulders of the animal. Depending on the artist, a centaur can look majestic or ridiculous, but there really isn't much room to experiment with the form, right?

Sounds like you haven't heard of the onocentaur. The earliest Greek descriptions of this creature sound a lot like our more-or-less modern understanding of the centaur, while slightly later accounts get the creature confused with wild dogs and even frightening demons. But by the time things got to the Romans, this monster got significantly weirder. Aelian — admittedly a Greek writer, but one who wrote in the second century and whose works would have been read by Romans — agreed that the onocentaur had the upper body of a human. But his description then states that the lower part was only the back half of a horse, leaving the onocentaur to totter around on two hooves.

Not to worry, however, as the creature was said to lean forward onto its soft human hands when it needed to run. Not that you would have been able to ask the onocentaur how such locomotion worked or how it felt to try and get soft human hands to act as feet. That's because the onocentaurs were said to be viciously aggressive and dangerous to humans who crossed their path.

The Plinian races

As intellectually advanced as Pliny the Elder was for his time, it's clear that ancient Romans didn't worry about primary sources. Neither did the people who came after Pliny's publication of "Natural History," as some were so taken by the monsters described in the book that they referred to some as the "Plinian races" or, more bluntly, as "monstrous races."

To be clear, Pliny was hardly the first ancient person to describe some of these quasi-human figures, but his account often proved to be the most gripping and widely available one. How could he not grab readers' attention, with tales of dog-headed people (the Ethiopian Cynamolgi) and the horse-hooved Hippopodes living on distant islands in or near the Baltic Sea? Then, there were the Panotii, which Pliny claimed were people sporting ears so long that the hearing appendages also acted as a kind of natural clothing. Meanwhile, the Abarimon could run fantastically fast, though their feet were turned backward.

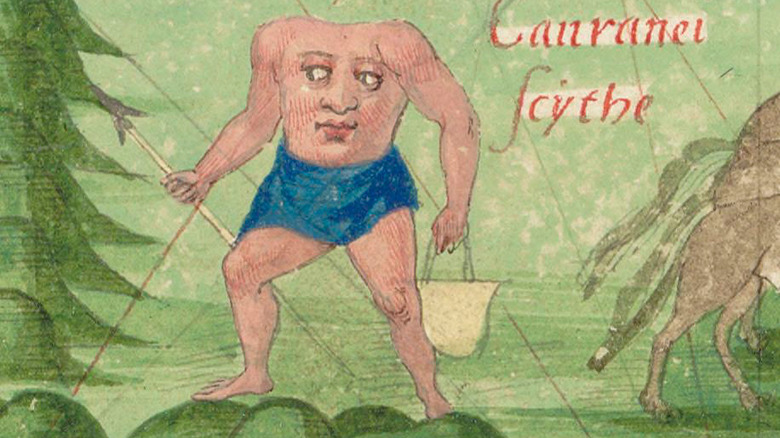

Then, there are the Blemmyae (pictured), the thought of which likely made ancient Roman readers shiver. Pomponius Mela, writing around A.D. 43, was one of the earliest Romans to mention them. And though Pliny rather casually tosses off a reference to these people in "Natural History," they would have been a frightful sight (if they had been real, that is). Referencing earlier writers, Pliny claims that members of this North African group have no heads at all, instead sporting faces straight in the middle of their chests.

Lemures

According to folklore, ancient Rome was stalked by many different ghosts. There were the lares, good spirits who didn't cause much trouble. So, too, were the manes, at least further back in Roman history. Later writers got them confused with the ghosts of individual humans or general ancestor figures, while others maintained that the term was a catch-all for spirits who hadn't made their alignment on the good-to-evil scale clear.

Then, there were the lemures. These were ancient Roman spirits who meant business — and their business was none too good. Some said that these frightful spirits were simply evil and existed to torment humans. Others, like the poet Ovid, supposed that the lemures were manes or ancestors gone bad because no one had been properly attending to their memory or they had unfinished business. Other Roman writers only took the opportunity to deride the whole idea of scary ghosts and anyone who believed in them. The idea was powerful enough that the spooky eyes and night calls of the Madagascar-based prosimians we call lemurs inspired the name.

Perhaps the strangest aspect of the lemures had to do with how the Romans attempted to please them during the Lemuria festival. Held on three non-consecutive days in May, this festival saw ancient Romans scrambling to appease family spirits by untying knots, walking barefoot, and tossing black beans about the house. Ovid claimed that this last trick was meant to distract the formless, vengeful lemures away from the living.

Manticore

According to Greek and Roman writers, you would have been hard-pressed to mistake the manticore for any other animal. Pliny the Elder, riffing on what earlier Greek writers had to say, claims that the manticore was a fearsome monster. Most strikingly, it was believed to have the head of a human being, though that human-like face sported three rows of teeth and sat atop the body of a lion. Not striking enough for you? Pliny also writes that the manticore was blood-red.

As if that weren't bad already, the manticore was supremely fast and had a scorpion-like tail that it could use to strike victims, sometimes with poisonous darts that it could launch into its victims and then re-grow for the next attack. Oh, and of course the creature was especially interested in gobbling up slow-moving, unwary humans. It was just as well that Pliny wrote it was believed to live somewhere in distant, vaguely defined Ethiopia. Other writers claimed that this beast lived in and was shaped by the harsh, arid environments of India or Persia, though quite a few also sniffed at the whole concept (perhaps wondering why Pliny seemed to buy into the manticore idea in the first place).

Cacus

Giants are already pretty odd when you think about them. It's not just their stupendous size (though that's definitely part of it). They're also depicted as bloodthirsty subhumans, from the super-sized Cyclops of the ancient Greek "Odyssey" to the main villain of Jack and the Beanstalk. Fueling these sorts of stories in ancient Rome was the archaeologically substantiated presence of real people living with gigantism, a growth disorder that made them much, much taller than average — but almost certainly did not induce any sort of bloodlust.

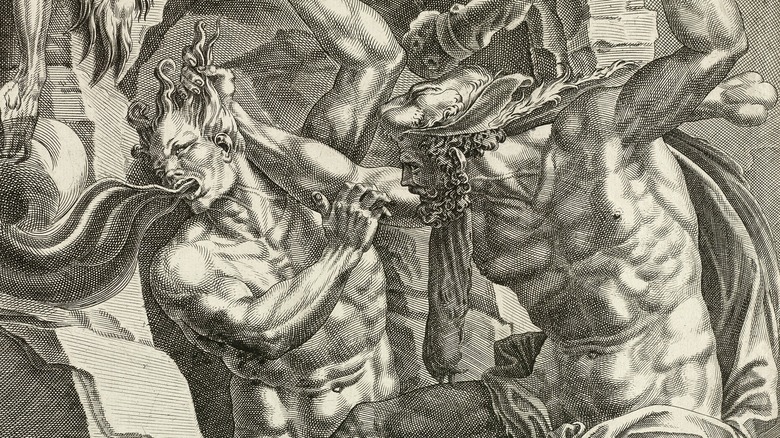

Rome had its very own homegrown giant who was supposed to have lived on the city's Aventine Hill, though he caused chaos before the settlement that became Rome was established on the site. Some tales said that Cacus was only a human cattle rustler who lived in a cave on the hill. Later accounts transformed him into a fire-breathing giant who faced off against Hercules. He was said to be the son of the forge god, Vulcan. But his divine heritage didn't do much for his personality, as Cacus' abode was decked out with the gruesome remains of animals and any humans who crossed him.

When Hercules seeks him out for the crime of stealing cattle, Cacus attempts to create a literal smokescreen in some tales or else goes straight to belching flames into the legendary hero's face. Whatever Cacus tried didn't work, however, as Hercules did him in with a club, and the cattle-hungry, flame-spewing giant of Latium was no more.

Amphisbaena

For quite a few people, snakes are creepy animals. With apologies to herpetologists, it's easy to understand why so many are unnerved by these limbless and sometimes deadly venomous creatures. They also generate a kind of fascinated horror for some. Just look at the list of serpents Roman poet Lucan lays out in his epic poem, "Pharsalia."

In this section of his lengthy work, Lucan is supposed to be telling the story of Cato the Younger, who faced off against Julius Caesar in North Africa. However, the poet gets sidetracked describing the many serpents supposedly encountered by Cato's forces. Some are pretty innocuous and some are full of venom, but one stands out as extra odd. That would be the amphisbaena, which Lucan says has two heads that look at one another.

Given that he was writing at roughly the same time as Lucan, perhaps Pliny the Elder heard similar stories. He may have thought they could use a little more detail, as his account of the amphisbaena in "Natural History" is a touch more involved, noting that the two-headed serpent is venomous and that its second head sprouts from its tail. However, he skirts obvious questions about how it eats or passes subsequent waste products. Given the impracticality of such a setup, it's clear that this monster is purely mythological.

Catoblepas

Cape buffalo (pictured) are already pretty terrifying. Besides the fact that these large African animals are not only real but seriously hefty — mature males can weigh close to 2,000 pounds — they are notoriously ill-tempered. Some of the more dramatic stories of its destructive power are overblown, but they remain a force to be reckoned with. These animals aren't afraid to fight back when cornered, using their tremendous bulk and those wicked-looking horns to do great damage to their enemies.

The fearsome Cape buffalo may have inspired Greek and Roman tales of the more fantastical catoblepas, which was also said to have lived in sub-Saharan Africa. While it reportedly had the body of a buffalo, things started to get strange when you considered other parts of the monster. Pliny the Elder wrote that its head was so heavy the animal walks around with its skull sagging toward the ground. Just as well, given that its gaze was so deadly that anyone who looked the catoblepas in the eyes dropped dead right away. Pliny then blithely moves on to the topic of basilisks, never bothering to explain or guess how a heavy-headed ungulate was able to murder someone with nothing more than a glance.

Strix

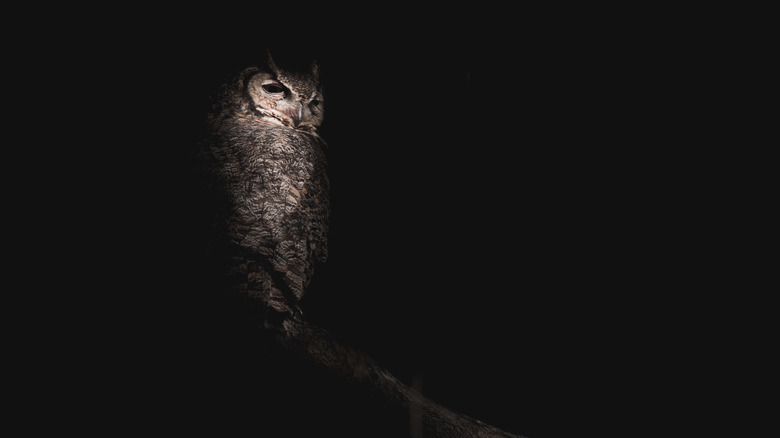

The strix is an ominous monster of Roman folklore that could be any number of vaguely defined but dangerous creatures. In the poem "Fasti," Ovid writes that an infant prince named Proca is attacked by bird-shaped beings he calls screech owls. Yet, these creatures don't behave like any screech owl modern folks know. Sure, Ovid's general description of beings with large heads, curved talons, sharp beaks, and gray feathers fits with owl-kind. But the strix behavior of swooping in on unattended infants and consuming the young humans is definitely not reported owl behavior. Others wrote that the strix was more like a bat. Yet more Roman authors claimed that talismans taken from the body of the strix could be used for all manner of things, from healing to killing to helping someone fall in love with you.

In general, the strix gained a reputation as a winged creature that hung around with witches, who could have used their winged associate (or parts of it) in their evil works. Roman accounts of the magic worker Medea, who wrought terrible revenge when ancient hero Jason discarded her for another woman, have her tossing strix bits into her deadly brew.

Here, facing the tale of the strix, Pliny the Elder finally decides to get skeptical. In "Natural History," he mentions that there are tales of screech owls that give milk to infants, presumably for nefarious purposes. However, he rightfully notes that owls do not lactate and dismisses this particular tale of the strix.

Cetus

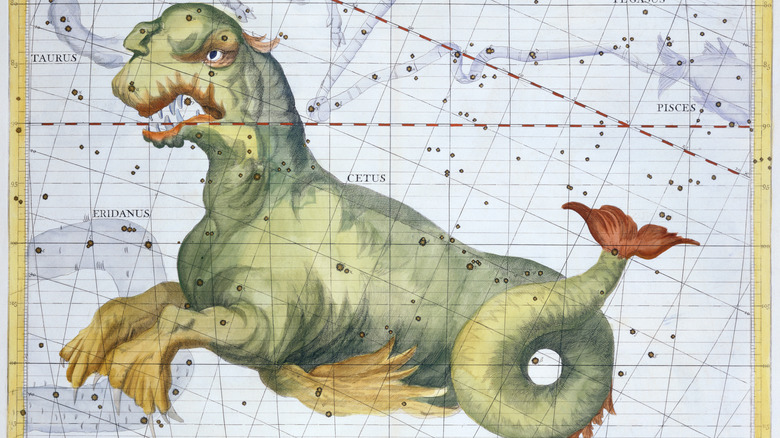

For the ancient people of the Mediterranean, the sea represented both great bounty and terrifying death. It's no coincidence that some of the earliest settlements in human history popped up near the sea thousands of years ago. Certainly, the Romans had a lot to thank for their proximity to the Mediterranean, which allowed them to develop a powerful navy to support their empire-building ambitions. But, still, the sea was large and could be treacherous no matter how mighty Rome's collection of trading vessels and warships was. Perhaps that's why Romans joined the other Mediterraneans in telling stories of the strange monsters that stalked the waves.

Broadly known as the cetus in Latin, this category of sea monster was already talked about plenty in ancient Greece, where the hero Perseus is said to have saved the princess Andromeda from being gobbled up by one. In his retelling of the myth in "Metamorphoses," Ovid refers to the monster as belua ponti, while Propertius calls it the monstris marinis — though neither does much to describe it. Even Pliny the Elder was a bit reticent here, though he says the Phoenicians worshipped a goddess named Ceto, who may have been a striking half-fish deity.

At least the first-century poet Valerius Flaccus comes through with a decent description of the Trojan cetus killed by Hercules. His version of the monster is almost too large to describe, with three rows of sharp teeth, a coiling body, and an eerie gray membrane over its eyes.