The Mythology Behind Centaurs Explained

Mythology is full of creatures that are half-man, half-animal, with centaurs and mermaids being perhaps the most famous of these hybrid creatures. Centaurs show up a lot in everything from ancient art to pop culture, and there's something about these half-man, half-horse beings that is just really, really cool.

They've been around for a long time, too. According to the Met Museum, some of the best examples of the ancients' ideas about the centaur are on the Parthenon. That was built between 447 and 432 B.C., says History, and by then, the centaur was already pretty ancient.

The Met has a bronze figurine of a man and a centaur that they date to the eighth century B.C., and it's possible that centaurs were already ancient at that point, too. The Cambridge University Press says that two terracotta centaurs were recovered from archaeological expeditions at the city of Ras Shamra-Ugarit. Those date back to the Bronze Age — which started in 3300 B.C., says History. While it's not likely we're going to get a much better date for when centaurs first started showing up in ancient tales, the takeaway here is that it was a long, long time go.

It's impossible to tell just why someone imagined these elegant yet inevitably barbaric creatures ... or, when they first mistook a man riding a horse for a single beast. What historians and scholars have learned, however, is a fascinating tale that says more about mankind than the mythological creatures they've invented.

They were the offspring of a cloud and a king ... maybe

There were a few different origins stories told about the centaurs. One of the most frequently told starts with the ever-feuding Zeus and Hera, with a pretty horrible man named Ixion thrown in for good measure.

The story — told by writers like Pindar and Diodorus Siculus (via Theoi) — says that Ixion was the king of an ancient tribe in Thessaly. He was due to marry, but to get out of paying his new wife's bride price, he simply killed his soon-to-be father-in-law. For whatever reason — to cause more chaos, probably — Zeus forgave him and invited him to Mount Olympus to have dinner and rub elbows with the gods (via World History).

Unfortunately for everyone, that's not all he wanted to rub. It wasn't long before Hera reported to her husband that Ixion had tried to assault her, and in order to determine whether or not she was telling the truth, Zeus — who was a singularly terrible husband — devised a test. He created Nephele, a cloud-nymph that took the shape of Hera and was put in front of Ixion. He, perhaps predictably, forced himself on Nephele.

Nephele gave birth to Kentauros, the first centaur — a creature who, Diodorus Siculus added, was one of the few who could navigate her ferocious rainstorms, thanks to his four legs. Meanwhile, Zeus had finally had enough of Ixion and condemned him to hell, chained to a wheel of fire for all eternity (pictured).

Or, maybe they were Apollo's grandchildren

Another version of just how the centaurs came to be goes back to the god Apollo. This, too, starts in Thessaly, and according to Diodorus Siculus (via Theoi), Apollo had a serious thing for some of Thessaly's nymphs. That included Stilbe, the daughter of one of the river gods. He hooked up with her, and she gave birth to two sons, Lapithes and Kentauros.

The story of what happened with Lapithes and Kentauros went way beyond a little sibling rivalry. Lapithes, says Brown University, was a great warrior who went on to pass all his wonderfulness on to an entire race. They were called the Lapiths, and they're going to become pretty important in centaur mythology.

Meanwhile, all the benefits and blessings that Lapithes inherited, Kentauros absolutely didn't. Deformed and ugly, he went on to found a whole race, too: After mating with female horses, the mares gave birth to the first generation of centaur.

The Guardian suggests that this is a bigger deal than it might seem at first glance. Early Greek mythology isn't just telling stories of how the seasons came about or what happens after death. There are also tales that tell of the ultimate triumph of order and light over chaos and darkness. The races spawned by the two brothers signify the struggle of the civilized world against complete chaos, and they meet in another tale.

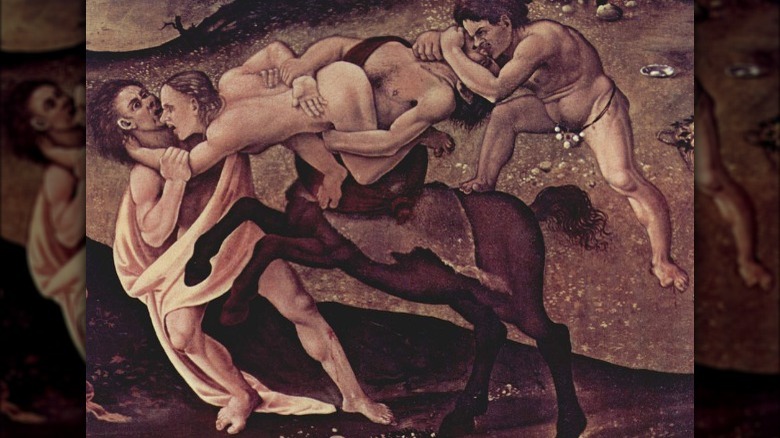

An ill-fated wedding

The story of the Trojan War forms the backbone of Greek mythology, and according to Ovid's "Metamorphoses" (via the University of Virginia), Nestor tells this story during a great feast celebrating (spoiler alert) the triumph of the Greeks over the Trojans.

Pirithous was a Lapith, while his half-brother, Eurytion, was a centaur and the leader of the Magnesian Kentauroi (via Theoi). Family being family, Pirithous invited Eurytion to his wedding, but as soon as the wine started flowing, things started going sideways.

Once the centaurs got just a little drunk, all sense of restraint was gone. Eurytion kicked things off in earnest, grabbing his brother's bride by the hair and dragging her off with intentions that, well, wouldn't work out well for Hippodame. His wild abduction of his brother's wife started a chain reaction, with his fellow centaurs joining in, grabbing whatever women they fancied and getting ready to head off into the wild blue yonder with them.

Also at the feast were Greek heroes Theseus and Nestor, who weren't about to stand for that sort of nonsense. It's Theseus who killed Eurytion in the middle of a shockingly graphic battle: Ovid writes of a centaur who "vomited great gouts of blood with brains and wine from wound and throat" (via Theoi), and that's an image that'll stick around. The hero (and, interestingly, transgender) Caeneus killed five centaurs, while Nestor recounted being front and center in the slaughter of more. The day ended with the Lapiths vanquishing the barbaric half-man beasts.

The wisest of all the centaurs

Let's talk about the teacher, mentor, physician, prophet, and musician, Kheiron. He, Psychology Today, adds, in addition to being the teacher of heroes that include Achilles, Perseus, Theseus, Ajax, and Jason, just happened to be a centaur.

And here's the thing — he's not actually related to all those other centaurs, as his origin story is completely different. He was the son of Kronos, as per Theoi, who's better known as the Titan who fathered then ate the oldest generation of Mount Olympus' gods. Zeus was the only one to get away, and here's where Kheiron comes in. Kronos was out looking for Zeus — who had been hidden away by his mother, Rhea — when he came across an ocean nymph named Philyra. Apparently deciding that he needed a little break, he hooked up with her — either in the form of a horse, or, he turned into a horse halfway through when he realized Rhea was looking in his direction. Either way, his dual nature sired a dual-natured son.

Psychology Today says Kheiron was abandoned, only to be found and raised by Apollo, then became a beloved figure in many hero stories.

Until, that is, his untimely death. Caught in the midst of a battle during Hercules' (also known as Herakles) labors, Kheiron was struck by one of the arrows that had been poisoned by the Hydra's blood. Immortal, unable to heal, and in agonizing pain, he gave his life in exchange for Prometheus' freedom and was placed in the stars as a constellation.

Hercules and Nessus

Unfortunately for Hercules, his run-in with one particular centaur doesn't go well.

Nessus — or Nessos — shows up for a series of events that will ultimately spell the end of everyone's favorite strongman. According to World History, he's the centaur that happens to be at the right place to lend Hercules and his wife, Deianeira, a helping hand. They're trying to cross the Evenus river, so Nessus offers to carry them to safety on his back. Halfway across the river, he starts to get a little frisky with Deianeira.

Hercules shoots and kills the centaur with a poisoned arrow, but Nessus lives long enough to make it to the other side and have a chat with the hero's bride. He promises her that his blood is magic, and if she ever finds Hercules straying from her and taking up with another woman, she could put some of the centaur's blood on his clothes, and he would be forever faithful.

"Forever faithful" doesn't crop up too much in Greek mythology, and sure enough, it wasn't long before Hercules won the princess Iole in an archery contest, as per World History. It's a complicated tale that eventually led to a jealous Deianira, who did as the centaur bid and doused her husband's cloak in blood — blood that contained the same poison that had been on the arrows that killed him. Realizing she'd been tricked, Deianira died by suicide, while Athena rescued Hercules from a life of eternal pain and gave him a place on Mount Olympus.

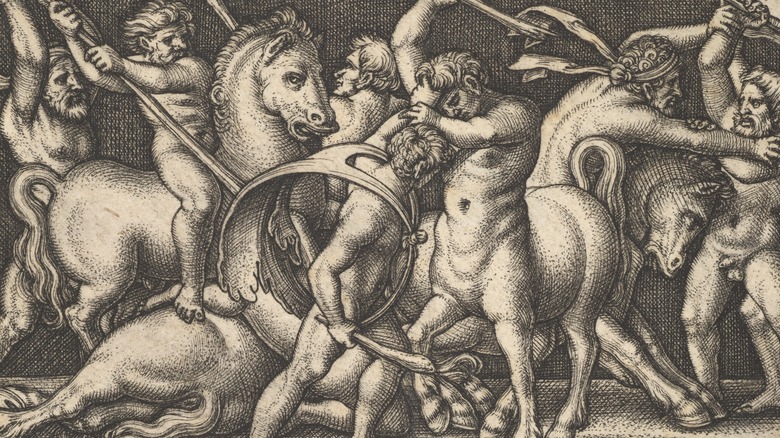

Dionysus had his own kind of centaur

Greek mythology is the dysfunctional family that just keeps on giving, and a deep dive into the world of mythological creatures digs up a fascinating subset: the Pheres Lamioi.

Various ancient writers disagree about what they are, so here's the gist, as presented by Theoi. It's accepted that they were originally demigods, who were native to and ruled over an Anatolian river called Lamos. It was there that Zeus sent his infant son Dionysus, believing he'd be safe there from Hera. (Hera was, of course, Zeus's long-suffering and oft-betrayed wife.) Not wanting to leave the baby alone, he instructed the native demigods to keep watch over Dionysus, and for their promise that they would, they were punished by Hera.

She was the one that turned them into centaurs, and here's where things get a little iffy. In art, they're often depicted as being harnessed to Dionysus' chariot (pictured), and they take the form of the standard sort of half-man, half-horse centaur that shows up a lot. Not all ancient writers agreed, though, with some — like Nonnus — giving them other odd features like the horns of an ox. He also described them as having long ears, weird tufts of hair, long fangs, and manes that connected their beards to their feet with one long ridge of shaggy hair.

Although these demigods-turned-beasts were perhaps unsurprisingly fond of Dionysus' wine as well, they were a little more loyal than their counterparts: Most died alongside him in battle.

Zeus accidentally had some centaur children, too

Aphrodite was one of the most popular of the Olympian gods, and this one's worth a little back story. While she's sometimes described as the daughter of Zeus, as per Theoi, she more commonly was said to have been born of the sea foam that surged when the Titan Kronos threw the severed genitals of his father — Ouranos, the sky — into the ocean. One could argue that technically makes Aphrodite Zeus' aunt, according to "Greek Mythology," by Hossen Cheytan.

Aunt or daughter, it's still a little disturbing that Nonnus wrote (via Theoi) that Zeus — determined to break any vows of fidelity he might have made to Hera with pretty much anyone and everyone — had his lecherous eye on Aphrodite. She, however, wanted absolutely nothing to do with him, and Nonnus said that she "fled like the wind from the pursuit of her lascivious father."

Zeus had apparently been ready, willing, and able, and when Aphrodite got away from him he fertilized the ground instead of the goddess. The ground was actually Gaia, the Earth (wife of the castrated Ouranos), and from that union came "a strange-looking horned generation."

They were known as the Kentauroi Kyprioi, or Cyprian Centaurs. Half-man and half-horse, they were said to also have the horns of a bull. It's believed that they took a place alongside Aphrodite as fertility spirits, so that's nice.

Atalanta and the Centaurs

When it comes to the wildly strong women of Greek mythology, Atalanta was up there. Abandoned by her father at birth and raised by a bear, she was one of the favorites of Artemis, goddess of the hunt. She was a skilled warrior, fighting and besting any man who challenged her ... including a few centaurs.

Atalanta's story is particularly interesting because there's a few different versions of it, and it's the one by second-century writer Aelian that gives some insight into centaur lifestyle. He wrote (via Theoi) that those living at the foot of the mountains could hear the constant sounds of hoofbeats, echoing down from the slopes where the centaurs lived. The first sign that they were making their way down to the land of men was the glow of their pine torches, and "the first sight of fire would have terrified even the population of a city."

These two particular centaurs were called Hylaios and Rhoikos, and under the guise of bringing gifts for a wedding, they tried to get close with the ultimate goal of assaulting Atalanta. She killed them first, though, with two well-placed arrows.

Centaurs as a conflict of the soul

There's an oft-repeated theory that the idea of a centaur came when someone saw a horse and rider from afar and didn't entirely know what they were looking at. When a rider is truly in-tune with his or her horse, it can look like they're moving as a single entity, and according to the "Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology," it's not an idea that's completely out of the question.

Centaurs were often said to be from the area of Thessaly, and it just so happens that the Thessalians were so good with horses that they spent much of their life in the saddle. It's possible that neighbors may have mistaken them for a singular creature, and that's kind of appropriate.

Throughout mythology, centaurs represented a duality, says Fordham Art History. Both animal and human with the desires of both, they depict a concept called psychomachia, or "conflict of the soul." (Interestingly, The British Library notes that a fifth-century poem by Prudentius — called "Psychomachia" — was one of the first allegorical works of European literature, suggesting it's an idea that many writers were concerned about.) It's an idea that was popular at the time artists like Michelangelo were creating stunning works of art featuring the centaurs, and as far as ideal Renaissance concepts go, the half-man, half-horse creatures were perfect when it came to examining a soul's struggle between intelligence, reason, and faith versus baser needs and desires.

They regularly appeared in medieval bestiaries

Centaurs didn't just jump from Greek mythology to modern fantasy; they've been almost surprisingly popular during all that time in between, too.

Medieval historian Thijs Porck took a look at how often centaurs showed up in the art and even on the coins of medieval Europe and found that they were pretty popular. Porck says many artists were probably familiar with the ancient Greek stories of the centaur and adds that medieval writers didn't just settle for the same half-horse creatures: They also added ones that were half donkey, too.

In some cases, they were used in much the same way they were in ancient Greece. In one 11th century text, Porck says they were used to illustrate the difference between clerics who answered to a higher power within the church and those who did not. It was the latter clerics that were connected to the centaur: Just like they were half-man and half-horse, the writer claimed these false clerics led dual lives of catering to a divine being while being free to indulge their base desires.

Centaurs show up in a lot of surprising places: There's one on the Bayeux Tapestry, which is the 11th century tapestry that tells the story of William the Conqueror. They've also been found carved into Viking longships, and one centaur — Kherion — often showed up in medieval manuscripts on botany.