The Untold Truth Of J. Robert Oppenheimer

Trigger warning: This article contains mentions of suicidal thoughts and depression.

For most of the general public, J. Robert Oppenheimer is perhaps best known for two things: heading the Manhattan Project, the wartime initiative that created a tool of horrific destructive potential, and the harrowing security hearing that precipitated his fall from grace. But beyond Oppenheimer's role as the father of the atomic bomb and the personal relationships and decisions that made him a target of government persecution, there are numerous other layers to the story of this brilliant but complicated man.

Oppenheimer made many other significant contributions to science that aren't discussed quite as often as his role in the weaponization of nuclear technology. He was an influential educator, an inspirational leader, and an exemplary scientist. At the same time, he dabbled in interests that veered more toward the spiritual — pursuits that, while not exactly rooted in the scientific method, had an evident impact on the theoretical physicist's methods and way of life.

With the benefit of hindsight, it could be said that Oppenheimer was a passionate seeker of knowledge who struggled under the weight of both academic pressure and the consequences of his earlier decisions. Near the end of his life, after fighting accusations of treason, he became the poster child for science being caught between the ethical pursuit of knowledge and the demands of political players. This is the untold truth of the man who was, as described by the Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, "one of the most remarkable personalities of [the 20th] century."

At age 12, he was invited to speak at the New York Mineralogical Club

J. Robert Oppenheimer was born on April 22, 1904, in New York. As told in Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin's biography "American Prometheus," Oppenheimer, whose father was a German immigrant, displayed both an aptitude for science and a predisposition for physical illness that did not go unnoticed by his protective parents. Thus, he was prohibited from playing with other children, spending most of his youth studying alone or in the company of his mother.

His encounters with his grandfather Benjamin ultimately served as the catalyst for his lifelong career as a scientist. Seeing the scientific potential in his grandson as he observed the latter playing with wooden blocks, the septuagenarian decided to gift Oppenheimer with an architecture encyclopedia and a starter rock collection with German labels. This sparked the young boy's interest in mineral collecting, but he realized that he was more invested in "the structure of crystals and polarized light" than in the rocks that he possessed.

After some years, Oppenheimer found himself corresponding with prominent geologists in New York. This led to them nominating Oppenheimer for membership in the New York Mineralogical Club and inviting him to give a lecture, unaware that they were discussing the complexities of Central Park rock formations with a 12-year-old boy. The reluctant child was convinced by his father to show up at the meeting, simultaneously amusing the audience with his youthfulness and wowing them with his expertise.

As a student, he was almost charged with attempted murder

In 1925, J. Robert Oppenheimer sailed to England to continue his education at Cambridge University, after practically breezing through his classes at Harvard. According to the Science History Institute, the speed at which he completed his Harvard courses actually made things more difficult for him later, as it meant he had glossed over some of the "fundamental knowledge" he would need at Cambridge and beyond. Worse, he was turned down as a mentee by Nobel laureate Ernest Rutherford, who was not impressed by his credentials. This, in addition to being forced to do laboratory work and sit through lectures, contributed to Oppenheimer's growing dissatisfaction with his life away from home.

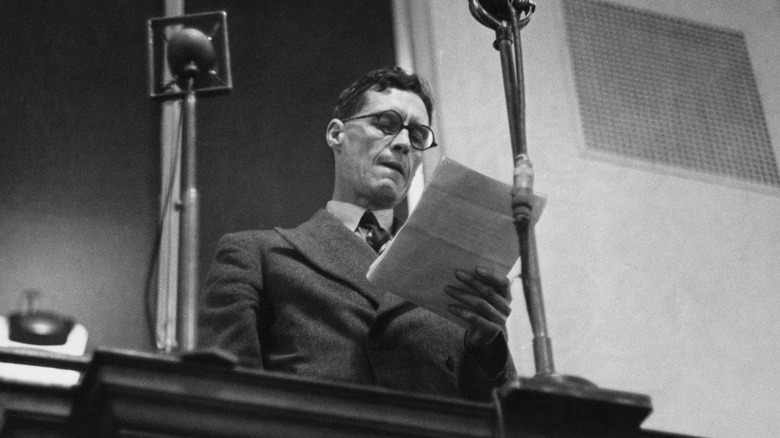

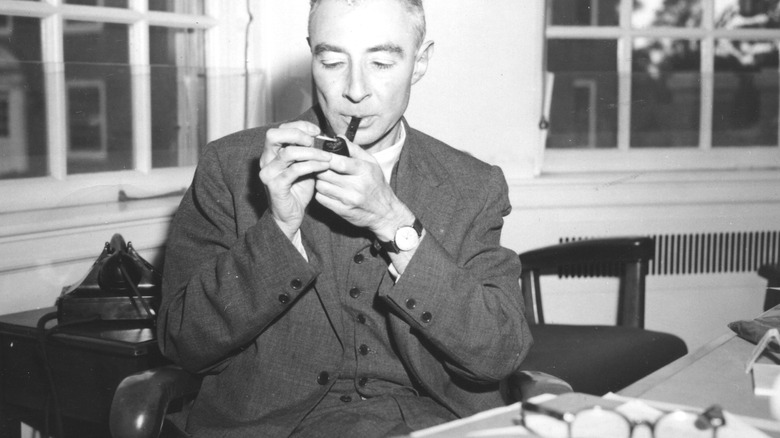

The negative shift in Oppenheimer's disposition reached its ugly climax in an incident that he himself recounted to his friend Francis Fergusson. Per his own admission (via "American Prometheus"), Oppenheimer injected an apple with poison and left it on the desk of his mentor, Patrick Blackett (pictured). Despite saying that he actually liked Blackett "very much," Oppenheimer hated that his tutor kept making him do more of the hands-on lab work he so despised. Luckily, Oppenheimer's attempt at Blackett's life failed, as the latter did not consume the fruit.

Had it not been for the intervention of Oppenheimer's father, the budding physicist would have been not just expelled, but also charged with attempted murder. Instead, the university put Oppenheimer on probation, and required him to see a London-based psychiatrist on a regular basis.

His university classmates once signed a petition to make him shut up

A year after his troubled stay at Cambridge (culminating in what the authors of "American Prometheus" described as "a winter of depression") and his near-expulsion, J. Robert Oppenheimer was in much higher spirits. Under the tutelage of pioneering physicist Max Born, Oppenheimer became a graduate student at the University of Göttingen in Germany. There, he found himself in the company of equally brilliant thinkers, became an intellectual superstar... and developed a habit that irritated his colleagues so much, they threatened to boycott Born's class unless the "child prodigy" could learn to behave.

During discussions, Oppenheimer would reportedly interject — regardless of whether it was a classmate or Born himself talking — and propose, with an air of superiority, what he thought were more efficient ideas. Tired of witnessing Born's milquetoast attempts at reprimanding Oppenheimer going over his seemingly swelled head, the class signed a formal petition to make Oppenheimer quiet down, lest they all walk out. Opting to avoid confrontation, Born left the petition on his desk for Oppenheimer to see. It worked, and the humbled student self-corrected his obnoxious behavior.

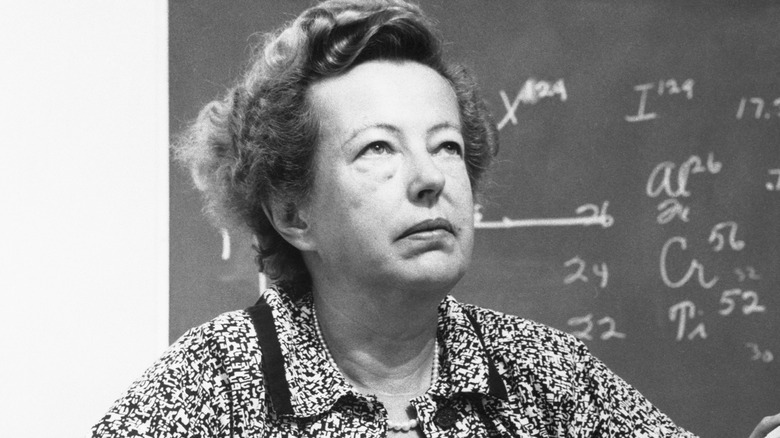

In a 1962 interview for the American Institute of Physics, historian Thomas S. Kuhn asked the petition's alleged instigator, Maria Goeppert Mayer (pictured), about the veracity of the story. The Nobel laureate's response: "I don't remember, of course I might have instigated it, if I'd been a student then ... But keep the story anyway, it's a nice story."

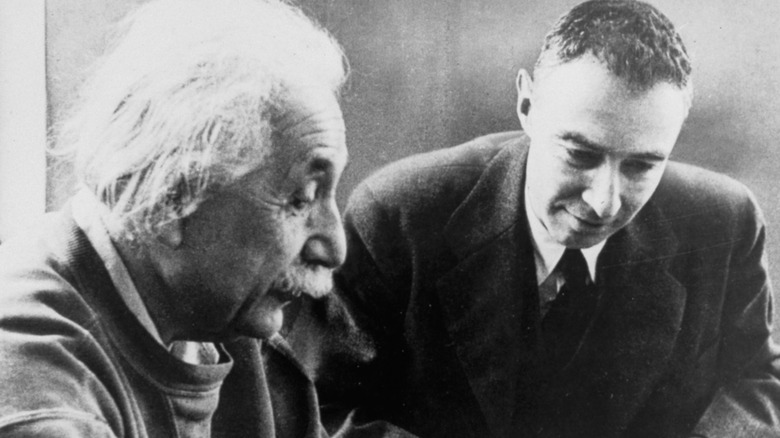

Oppenheimer v Einstein: dawn of black holes

Black holes have become such a staple of both scientific discussions and popular culture that it may be hard to imagine a time when scientists weren't even fully aware of their existence. Perhaps it's even more bizarre that Albert Einstein, the person we tend to associate with the word "genius," once asserted that such cosmic phenomena were impossible. Interestingly, it was J. Robert Oppenheimer and his colleague Hartland Snyder who proposed the idea that these astronomical objects could exist; they published their analysis mere months after Einstein published his own attempt at proving that they couldn't. In an ironic twist, they used Einstein's theory of general relativity as the foundation of their musings.

In their 1939 work "On Continued Gravitational Contraction," Oppenheimer and Snyder pondered the end of a massive star's life (when it depletes its own fuel supply). Instead of it collapsing into a white dwarf, the co-authors proposed that the dying star would progressively contract due to its own gravity, at a rate that would prevent even light from escaping from it. Basically, they were thinking about black holes nearly 30 years before the term "black hole" would even be coined by physicist John A. Wheeler. While it was by no means a perfect paper, they were definitely on to something. Unsurprisingly, no one paid much attention to Oppenheimer's paper at the time, and it was an area of research he would never revisit.

Oppenheimer never won a Nobel Prize, despite being nominated three times

Given J. Robert Oppenheimer's scientific significance (and perhaps, historical infamy), it may be surprising to know that he never received a Nobel Prize. He was nominated three times for the prestigious award in the field of physics: first in 1946, when he lost to P.W. Bridgman; then in 1951, when the prize was given jointly to Sir John Douglas Cockcroft and Ernest Thomas Sinton Walton; and lastly, in 1967, when it was awarded instead to Hans Bethe. This may understandably seem like a gross injustice that can never be corrected, since the prize can only be awarded posthumously if it was announced before the recipient's death, according to the statutes of the Nobel Foundation. However, a closer look at Oppenheimer's track record prior to the Manhattan Project reveals why he never won.

For starters, despite the fact that he did receive acclaim in the scientific community as a pioneering mind in theoretical physics, the volume of his actual published research was less than impressive. "Many of his colleagues and critics point out that his production of significant papers was surprisingly thin," explained historian James Kunetka to the Los Alamos National Laboratory, adding that the number of papers Oppenheimer co-authored with his students far exceeded that of his solo research works. Plus, Oppenheimer never published a breakthrough discovery or proof of an existing theory.

Basically, while there was no question about Oppenheimer's brilliance, his work simply didn't exhibit what the Nobel committee was looking for.

J. Robert Oppenheimer had mystical and religious interests

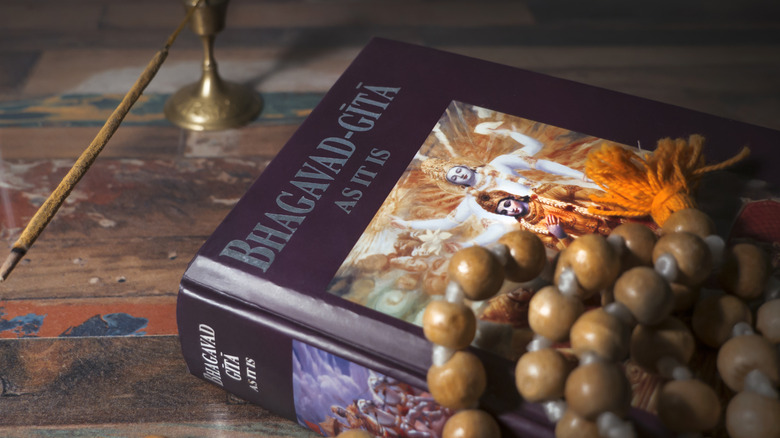

At a young age, J. Robert Oppenheimer displayed a passion for poetry, a flame that stayed lit even as he pursued a career in physics. Enthralled by both the beauty of language and the challenge of learning, Oppenheimer studied Sanskrit, a language that The New Atlantis describes as "a notoriously difficult [one] to acquire." As stated in "American Prometheus," Harold Cherniss, an American historian and Oppenheimer's friend, was the one who introduced the physicist to his Sanskrit tutor, encouraging what Cherniss referred to as Oppenheimer's "taste for the mystical, the cryptic." Learning Sanskrit paved the way for Oppenheimer to read the sacred Hindu text the Bhagavad-Gita. In his letters to friends, Oppenheimer gushed about the ancient scripture, calling it "the most beautiful philosophical song existing in any known tongue."

While there is little evidence that Oppenheimer was particularly religious, he was seemingly drawn to the metaphysical (and at times contradictory) nature of religion itself. His friend and fellow physicist Isidor Rabi shared that he once told Oppenheimer that Christianity was a confusing "combination of blood and gentleness"; Oppenheimer reportedly responded that it was what attracted him to the religion.

This fascination with the supernatural was likely why Oppenheimer reacted the way he did when he saw the successful detonation of the Trinity test in New Mexico on July 16, 1945. Instantly realizing the impact of his creation, he famously remembered a line from the Bhagavad-Gita that encapsulated the moral quandary he was in: "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds."

He holds a less widely known (but no less impressive) record

In 1947, after his time at the Los Alamos National Laboratory and a teaching stint at the California Institute of Technology — a job that he was no longer passionate about, per "American Prometheus" — J. Robert Oppenheimer accepted an offer from the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) at Princeton, New Jersey. According to the IAS, Oppenheimer was the institute's third director, as well as its longest-serving one; he held the position from 1947 to 1966.

Aside from presenting him with a new career challenge, it also helped that the position came with an annual salary of $20,000 (a little over $273,000 in today's money), as well as rent-free use of a three-story manor "surrounded by 265 acres of lush green woodlands and meadows" as his residence (via "American Prometheus"). Interestingly, the job was pitched to him by Lewis Strauss, the man who would later spearhead the infamous trial that stripped Oppenheimer of his security clearance and cast doubt on his loyalty to the United States.

The Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society describes Oppenheimer's tenure as IAS director favorably. Under his leadership, the institute saw an increase in inspired young physicists, encouraging an atmosphere of fast-paced idea development. In a 1955 interview, Oppenheimer likened the IAS to a decompression chamber: "It's to help men who are creative and deep and active and struggling scholars and scientists to get the job done that it is their destiny to do."

He threatened to sue a playwright

It's one thing to be grilled by your own government in an attempt to prove that you committed treasonous acts, and another matter entirely to live to see it being artistically reimagined for theatrical entertainment. Perhaps that's why J. Robert Oppenheimer was so incensed by a play based on the transcript of the 1954 Atomic Energy Commission hearings that he threatened to sue its playwright (via Time Magazine).

Crafted by German writer Heinar Kipphardt, "In der Sache J. Robert Oppenheimer" ("In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer") was first shown to audiences in 1964 in Berlin and Munich, and was later released as a TV movie in 1981. At the time of its premiere, Oppenheimer was still serving as the director of New Jersey's Institute for Advanced Study. To say that he was displeased by its portrayal of the proceedings is an understatement.

As the story goes, Oppenheimer took particular offense at what he labeled as "improvisations which were contrary to history and to the nature of the people involved." This included the way the play claimed that physicist and Manhattan Project team member Niels Bohr had reservations about Oppenheimer's endeavor, allegedly due to the shadow of government interference looming over them. Oppenheimer also vehemently rejected the play's portrayal of him as someone who regretted his part in Los Alamos. Per The New York Review, the producers responded by omitting "offending passages" from Kipphardt's play to appease Oppenheimer. Ultimately, the case didn't push through.

An asteroid, a lunar crater, and a rare mineral are named after him

J. Robert Oppenheimer will forever be associated with the atomic bomb and nuclear warfare, but it isn't the only way his name has been immortalized in science. For starters, there's asteroid 67085 Oppenheimer: Located in the region of space between Mars and Jupiter, it was discovered on January 4, 2000, by amateur astronomer Stefano Sposetti at the Gnosca Observatory in Switzerland.

The theoretical physicist's name has also been used to identify a specific impact crater on the moon. Found on the satellite's far side (meaning the side of the moon that can never be seen from Earth), the Oppenheimer crater seems to be almost circular, based on its appearance on the Lunar Farside Chart. Formerly known as Crater 382, the International Astronomical Union approved its name change in 1970, following a longstanding tradition of naming lunar craters after deceased engineers, scientists, and explorers who have made significant contributions to their fields of expertise.

One need not look to the stars to find other scientific tributes to Oppenheimer, though. Oppenheimerite is a pale greenish-yellow uranium mineral with a glass-like luster and an elongated, prism-like external shape. Initially found in Utah's Blue Lizard mine in San Juan County, it is said to be incredibly hard to find. Aside from possessing a novel crystal structure, Oppenheimerite is easily dissolvable in water.

The J in his name stands for nothing, according to him

When The New York Times published an article about J. Robert Oppenheimer's life two days after his death in 1967, it began with the rather curious line: "Starting precisely at 5:30 a.m., Mountain War Time, July 16, 1945, J. (for nothing) Robert Oppenheimer..." Which raises the question: What does the "J" in "J. Robert Oppenheimer" stand for?

One would think this shouldn't even be a topic for discussion. After all, as "American Prometheus" confirms, the physicist's birth certificate officially states that his full name is "Julius Robert Oppenheimer," with his first name taken from his father. Interestingly, though, the physicist provided a peculiar answer to questions about his first initial on multiple occasions: The "J" stands for nothing. In fact, per the Los Alamos National Laboratory, Oppenheimer asserted to the U.S. Patent Office in a 1946 note that "J" was the entirety of his first name. With that said, it didn't really matter much to Oppenheimer or his colleagues, who preferred to call him "Robert" or "Oppie" (a nickname he earned from his students at the University of California, Berkeley, in the early 1930s).

Whatever the true reason may have been regarding Oppenheimer's insistence that his first name was simply "J," it certainly wasn't a hint of any cracks in his relationship with his father. In fact, until his death in 1937, Julius maintained solid connections to his sons, following the death of his wife Ella six years earlier.

His mental and emotional health suffered — before and after his most infamous work

As recounted in "American Prometheus," during his probationary period at Cambridge, J. Robert Oppenheimer was required to see a Harley Street psychiatrist. Unfortunately, they determined that Oppenheimer was exhibiting signs of dementia praecox (an obsolete, inaccurate term for schizophrenia). Around this time, Oppenheimer was having suicidal thoughts, a state that he later admitted was becoming "chronic."

Curiously, Oppenheimer maintained that he felt no guilt in the role he played in the development of the atomic bomb. He felt that the pursuit of knowledge was an "organic necessity," even if it led to the creation of such a horrific weapon. However, he also asserted that the Los Alamos scientists had a responsibility to help the world navigate the "grave crisis" through global atomic energy regulation initiatives and solidarity in the scientific community.

Tragically, it may have been the 1954 security trials that ended up breaking Oppenheimer's spirit. Questioned for 27 hours about his past connections with left-leaning parties, Oppenheimer admitted that the trial had left him with "very little sense of self." As physicist Freeman Dyson wrote in The New York Review, Oppenheimer was "sick and depressed" in his twilight years, and not just because of the throat cancer that would eventually kill him: "His days as a scientist were over. It was too late to cure his anguish with equations."

In 2022, 55 years after Oppenheimer's death, the U.S. Secretary of Energy overturned the decision to revoke his security clearance.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org