Things That Were Normal In Schools 70 Years Ago

The 1950s are popularly known as the height of American economic prosperity, known as a time of high fashion, suburbanization, a large middle class with money to spend, post-war peace and tranquility before the societal fervent of the Vietnam War era. It was also a time of changing childhoods, when children mostly went to school rather than going to work and the word "teenager" was coined to describe that phase of adolescence that was no longer considered the beginning of adulthood.

Although the 1950s was very different to today's society, schooling as we know it today is by and large a product of that era. Large, consolidated public, mixed-gender schools became the norm then, partly due to the suburbanization of the country. Insofar as the curriculum is concerned, most of it would still be broadly recognizable today. But there were some stark differences, too, ranging from strict adherence to dress codes to segregation that separated students based on race. And since the '50s were also a time of transition for the nation following World War II, some of the older institutions, such as one-room schools, were still common in parts of rural America.

Here are some things that were commonplace in the 1950s that have largely vanished from American schools today.

Guns

The 1950s-era school policies on guns would probably terrify most modern Americans. The Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990 makes it illegal to possess firearms in schools, while mass school shootings are at historic highs. In the 1950s, however, school shootings were rare, while mass shootings were completely unheard of. This didn't mean you wouldn't find firearms on campuses, though, as guns were commonplace in schools, and in some cases, actively encouraged as part of extracurricular activities.

The gun landscape of 1950s America had fewer regulations. Back then, children could legally buy mail-order guns, there was no ATF Form 4473 (established in 1968) for background checks/transaction records, and kids could bring their guns into schools and store them in their lockers or cars. According to the people interviewed for a National Review article on the subject, in many areas of the country, it was normal for children to go to school with their firearms after a morning hunting trip or go on an afternoon hunting trip straight from class.

The ubiquity of guns in schools fostered a culture of unisex, extracurricular shooting clubs. KTOO of Juneau, Alaska, interviewed a handful of people who attended the local school system in the 1950s. One of them, a woman named Karleen Grummett, recalled a gun range in the basement of the local elementary school, where students were taught shooting and safety, even being able to earn certification in rifle marksmanship. And it was not just in Alaska, where 65% of people own guns today. Even states with strict gun laws such as New York hosted school shooting teams in the past.

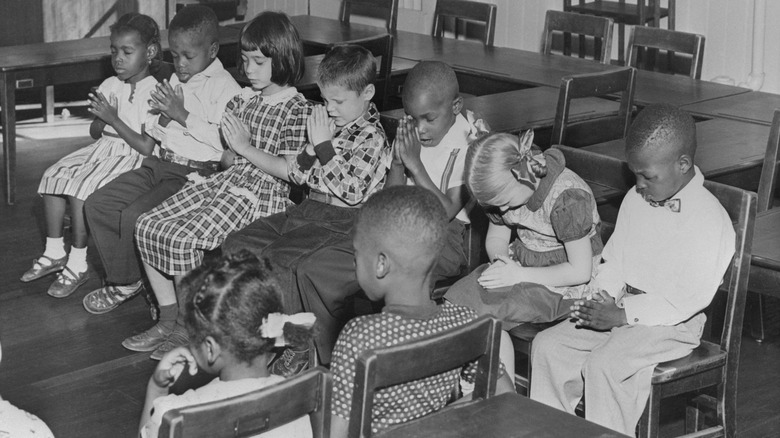

Organized prayer and Bible reading

School-sponsored religious activity in public schools has been illegal ever since the Supreme Court struck down any sort of school sponsorship of religious prayer or Bible reading in the 1962 case Engel v. Vitale. But before that, although it was gradually receding, school prayer was still commonplace in 1950s America.

Back then, around 40% of American schools had some form of school prayer or Bible reading, including recitation of the Christian Lord's Prayer. In some states, it was even required by law. New York's Board of Regents, for instance, required the morning recitation of a non-denominational prayer that went, "Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers and our Country." This was the prayer that triggered the 1962 lawsuit. Pennsylvania, whose law was overturned in the 1963 case Abington v. Schempp, required "At least 10 verses from the Holy Bible [to] be read, without comment, at the opening of each public school on each school day." Both states, however, allowed parents to opt their children out.

The Vitale case argued that organized prayer discriminated against students of different faiths and non-religious students by making them pray against their beliefs, but it was not voided on these grounds. Instead, SCOTUS ruled that organized prayer was a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, whose guarantee of equal protection, SCOTUS ruled, forbade states from favoring one religion over another – previously something that applied only to federal institutions. Today, it's possible organized prayer might make a comeback, as Texas has attempted passing bills to allow it.

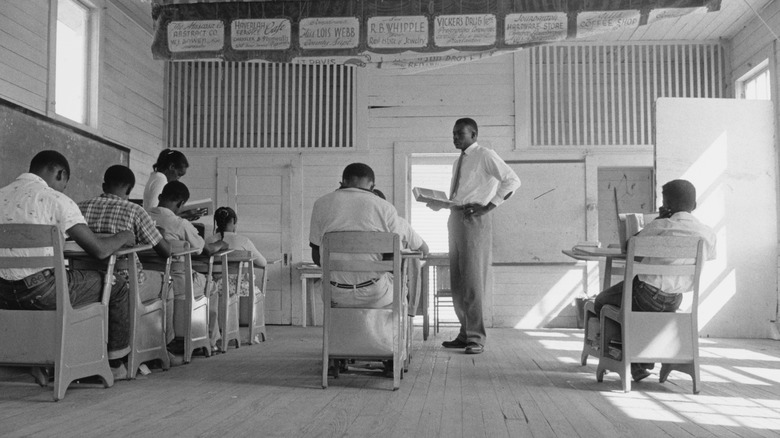

Legal racial segregation

Today, if a person lives in a particular school district, he gets to attend the local public school – no questions asked. In 1896, the Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that this was not the case, finding that as long as available school facilities were equal, students could be denied enrollment based on race. This "separate but equal" doctrine was still in force in numerous states in the 1950s.

For Black students, the ruling meant they could not attend schools in their districts that were considered "white-only." A handful of people interviewed by filmmaker David Hoffman recalled that instead, they attended small, dilapidated, one-room wooden schools, minimally equipped and funded, often with just a wood stove for heating. One woman recalled being asked to use a microscope in college but did not know how because her underequipped segregated school did not have them.

Eventually, the issue made it to SCOTUS when five lawsuits from across the Jim Crow South and Kansas were combined into Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. It challenged the "separate but equal" doctrine as unconstitutional. The court unanimously ruled that institutional school segregation was a violation of the 14th Amendment's equal protection clause. If African Americans lived in a particular district and paid taxes, they were entitled to use its schools. The decision drew ire at the time due to Chief Justice Earl Warren's reliance on social science rather than previous constitutional precedent – although there was not much of that to work off of. The decision stood, leading to measures to overturn school segregation – sometimes with the backing of the U.S. military.

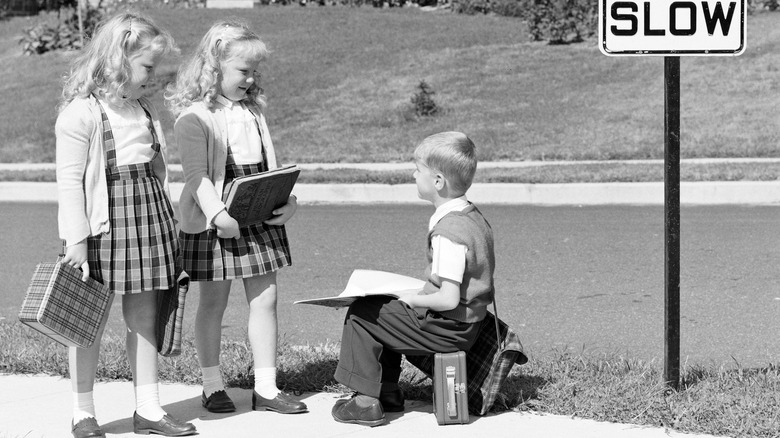

Elementary school children walking to school alone

Today, it is hard to imagine letting elementary- or middle-school-aged children walk to school or take public transport by themselves. One woman was even arrested in 2014 for letting her 7-year-old walk to the park alone. But in the 1950s, letting young children walk to school unaccompanied was normal and expected.

In 1950, school buses were just becoming a national phenomenon, following the adoption of national standards in 1939. But in places where transportation was still spotty, such as rural America, children often still had to walk to school. Even in the well-connected suburbs, if parents had to work or there was no car available, children were on their own. So many of them walked. A survey from Slate found that around 70% of respondents who grew up in the 1950s were allowed to walk over one mile away from home by the time they were in 3rd grade (around 8 years old) – including to school. Today, the situation has flipped, as most parents wait until middle school, or in some cases, high school, before letting children go out on their own.

Although most children were going to school alone in 1950, the decade introduced the danger of car-related accidents thanks to increasing ownership and suburbanization. In response, authorities put out videos to teach children going to school alone how to be safe on the street. This included listening to crossing guards, looking both ways before crossing the street, and not accepting rides from strangers – typical safety rules that most children still learn today.

One-room schools

For the vast majority of American history, one-room schools educated the nation, bringing together children of different ages under one roof and one teacher. Although they seem like a relic of the 1880s Great Plains, many rural students were still attending such schools as late as the '40s and early '50s. Among rural African Americans in the Jim Crow South, one-room schools were often the norm.

Education in one-room schools was a bit different, even by 1950s standards. Whereas in most 1950s schools (the same is true today) teachers led age-segregated classrooms with a focus on one subject, students at one-room schools were separated by ability and often had to learn independently or collaboratively.

Because one teacher could not teach every subject to 30+ students of different ages in a lecture-style class as today, students at a one-room school often had to independently figure out work assigned by the teacher while he or she was busy testing and evaluating other students – usually through recitations. At the time, "recitation" did not mean rote memorization, but demonstrating proficiency in a skill, such as math, handwriting, or showing a knowledge of assigned reading or geography.

Although there were still many one-room schools in 1950s America, they were on their last legs. Urban flight, the appropriation of rural lands for suburbs, and school consolidation through state law resulted in most of them closing down by the 1960s. Their students were sent to larger public schools for the most part, although approximately 400 still remain in the most isolated, rural parts of the United States.

Corporal punishment

Discipline in modern American schools varies tremendously, ranging from detention to sending disruptive children out of the classroom to suspension. Some teachers have complained that modern discipline is too soft. Regardless of where one stands on that debate, corporal punishment is by and large no longer part of school disciplinary procedures, existing only in some localities south of the Mason-Dixon line. In the 1950s, however, it was the norm.

The kind of discipline in 1950s schools is best understood through personal experiences. One man, writing for the Buchanan County Independent, noted that corporal punishment existed in many forms. There was knuckle-smacking with a ruler or paddling/caning. There were also more Byzantine punishments, such as having to stand on one leg or being forced to stand on one's tiptoes while keeping the nose inside a ring against the blackboard.

What could one do to merit such a punishment? According to a former 1950s Catholic school student writing in Newsweek, it was easy to get on the nuns' bad side. Talking back, talking out of turn, and acting up at Mass were all grounds for being smacked in the face. For girls, the punishment for offenses such as having a skirt that was too short was being rapped on the knuckles with a ruler.

Interestingly, 55% of Americans, according to a 1954 Gallup poll, approved of schools using corporal punishment on their children. It was not until the 1970s that states started banning the practice, in part due to parents' belief that they should be their children's primary disciplinarians – not schools.

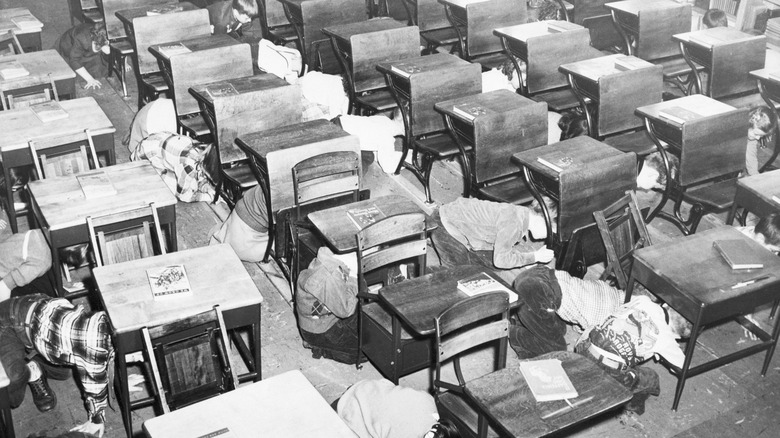

Duck-and-cover drills

In the 1950s, there was the pervasive fear that the Cold War could go nuclear. To "prepare" U.S. students for a potential Soviet nuclear attack or air raid, the Truman Federal Civil Defense Administration created the famous "duck and cover" videos.

The movies taught children, using a cartoon turtle, how to recognize a nuclear explosion and protect themselves from it by ducking under desks and pressing their faces against their knees to shield them from the flash of the blast and debris. They were also taught to use alternative cover when not in the classroom, such as walls and fallout shelters.

While the duck-and-cover drills were useless for surviving direct nuclear blasts, the drill was likely meant to teach children how to protect themselves from a nuclear attack or air raid occurring in their vicinity, since 1950s-era nuclear strikes were survivable outside the immediate blast radius. The threats outside the immediate impact zone were things like blinding lights that could ruin eyesight and shockwaves that could shatter windows and damage buildings. Thus, the duck-and-cover drill could actually have been effective against such dangers.

Despite some potential utility, the drills' opponents viewed them as fearmongering. Catholic peace activist Dorothy Day accused the Eisenhower administration of using tactics like air raid sirens and these drills to scare people into supporting aggressive stances abroad in her 1955 pamphlet titled "Fear is now the American way of life." She, alongside other anti-war activists, refused to take part in duck-and-cover and was arrested.

Strict dress codes

Most American students enjoy broad freedom of dress in public school, as long as they do not contravene rules of public decency. In the 1950s, things were different, as described by filmmaker David Hoffman, who grew up in the suburbs of Long Island. He recalled that student dress was meant to project a dignified image of American youth to the world.

Hoffman recalled that the "in" styles for 1950s girls included tight, waist-accentuating belts, dresses, half-length pants, and tight tops. In school, however, skirts were expected to go below the knee. In Catholic schools, the nuns even measured the distance between the hemline and the ankle to catch violators. High-necked tops were a must, but they could not be too tight (form fitting was acceptable). Schools also banned half and three-quarters-length pants like pedal pushers, while hair had to be shoulder length or longer – no pixie cuts.

For boys, the dress code forbade things like leather jackets, which were associated with greaser gangs and other "undesirable" elements of society, and long hair. Instead, they were expected to dress in neatly pressed slacks and button-down shirts or polos.

The schools justified the dress codes, saying that they improved the learning environment and created a safer environment for girls, although Hoffman said it was really a matter of controlling the student body. Clothing was a "disciplinary tool," as violators were punished with public shaming. The emphasis on conformity ultimately resulted in the backlash among youth that led to the 1960s counterculture movement.

Boxing teams and state championships

Boxing is a rare sport at American high schools. It still exists here and there, but generally, school officials refuse to allow it due to liability concerns – even though it is not banned outright. Seventy years ago, however, high school boxing was common and enjoyed a similar prestige to football in parts of the United States.

The sport was popular in poorer areas of inner cities and rural America, especially in southern states like Louisiana. That state even had a government-sanctioned school league, according to local outlet Evangeline Today. The regular season was around six months long, followed by a state championship.

High school boxers in Evangeline were treated like celebrities. The matches regularly drew thousands of spectators, students and community members alike. The state championship drew so many people that it eventually had to be moved to LSU's 12,000-seat John Parker Coliseum in Baton Rouge. Competitors were escorted in and out of the stadium by police, making these young athletes feel just like the pros.

After its heyday in the mid-'50s, the sport abruptly disappeared from America's high schools at the end of the decade and the early '60s. Louisiana withdrew its endorsement of the sport in 1958 at the request of Catholic schools. Similar moves followed nationwide, while the NCAA axed it in 1960 after a college boxer from Wisconsin died – even though he likely died from an aneurysm rather than a boxing-related injury. This was a prelude to a general backlash against the sport, with doctors calling for its total ban on medical grounds by the 1980s.

Priests and nuns

As Catholic schools are shuttered due to declining enrollment and financial woes, older alumni might wistfully recall the 1950s – the golden age of American Catholic schooling. At the time, Catholic schools taught 80% of all private school children and 10% of the total student population. They were also stereotypically known as "places where all students had to wear uniforms and bad students got their knuckles rapped or their ears pulled by nuns," per The New York Times.

Catholic schools today are mostly run by laypeople – that is, non-clergy. The presence of clergy, apart from the occasional nun or priest serving as principal or school chaplain, is rare. In the 1950s, however, nuns and priests ran the show as teachers, administrators, and disciplinarians.

However, the 1950s were also the last days of the nun-dominated Catholic school. The United States experienced a large fall in the number of new priests and nuns starting in that same decade, according to a study by the Catholic outlet The Pillar. With the collapse of religious vocations, the smaller number of priests still had to keep the same number of parishes running, leaving less time for teaching. Thus, schools had to hire laypeople.

The change had financial ramifications for Catholic schools. Tom Otten, a layman who worked in the Archdiocese of Cincinnati's school system, told WCPO that nuns and priests were less expensive to employ since they did not receive salaries, keeping costs down. Lay teachers, however, needed to be paid salaries in line with the cost of living, which translated to higher operating costs and higher tuition.

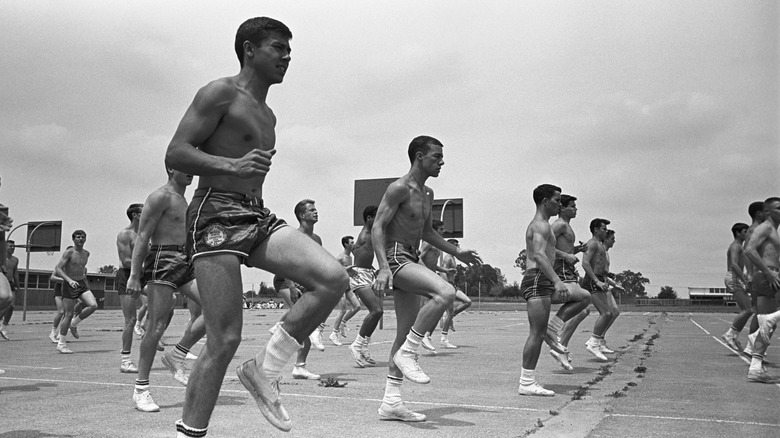

Phys-ed as a matter of national security

Today, physical education class has mostly been relegated to a period of playing a team sport, without much emphasis on the actual fitness base needed to play these sports, or cut entirely. The result has been an increase in overweight and obese children and type II diabetes. In the 1950s, there were similar concerns, especially since overweight and obese men would make poor soldiers in a hypothetical Third World War. To combat these concerns, tough, military-style fitness programs arose in schools under federal direction.

The fix actually started in 1960, when President John F. Kennedy published an op-ed in Sports Illustrated bemoaning the American's increasingly sedentary lifestyles and fitness decline due to office jobs. Over one-third of youth were failing basic physical fitness tests. Noting the ancient idea that a healthy body translated to a healthy mind, the president urged schools to develop their own programs in conjunction with state and local governments. The results were impressive. Among the most famous results of Kennedy's fitness drive was the creation of the LaSierra fitness program.

The LaSierra fitness program, developed in early 1960s California, was meant to give all athletes a level of conditioning equal to that of a varsity football player. The boys sorted into color-based teams (white, red, gold, and blue), earning promotion through a test. Some of the highest-level tasks were tough. They included floating while having one's arms and legs bound, doing extension pushups (only 1 in 30,000 boys nationally achieved it), and climbing a pegboard seven times.

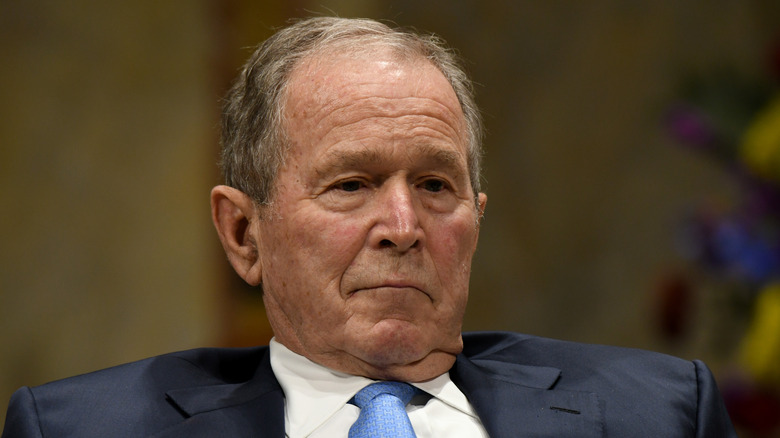

C averages in college

Today, having a "C" grade on one's transcript can be a death sentence when it comes to elite college admissions. Earning such a grade on a college exam or class often sends students into a panic. Think of how often President George W. Bush got made fun of for having a "C" average at Yale (77 by numbers). But in the 1950s, a "C," which historically meant "average," was, as one would expect, the most common grade.

According to a report from Los Rios Community College, the average GPA in the 1950s and early 1960s was 2.5 – a "C" or "C-" depending on the scale. In the late '60s and '70s, however, the average GPA increased to 2.8 at public and 3.1 at private colleges). Today, the average is nearly 3.0, and 3.3 at private colleges – much higher than the 1950s average.

The report notes that professors began artificially inflating students' grades to help them avoid the Vietnam draft – an idea supported in the data given that grade inflation coincided with the height of anti-war protests. Before 1971, good academic performance meant a deferment, while unsatisfactory (below average) performance meant the front lines.

The study blames the second spike of grade inflation in the 1980s on skyrocketing college tuition and the transformation of collegiate education into a product. As tuition increased and college admissions became the high-stakes game of today, students expected a good ROI on their work and investment – namely the degree and a good GPA to get a job. The only schools that maintain 1950s grading trends are community colleges, whose averages still cluster between 2.5-2.7.

Paying your way through college

The cost of a four-year college degree has skyrocketed. Average tuition is now nearly $37,000 per year, while student loan debt is approaching $1.8 trillion. While it is still possible for in-state students to work through college to cover at least some tuition at public universities, it is virtually impossible when tuition is equivalent to a year's full-time salary. In the 1950s, however, as colleges boomed and university ranks swelled, in part thanks to the 1944 GI Bill, it was possible to work one's way through college.

The GI Bill offered one year of tuition per tour of duty served – up to $500 per year. For those not receiving benefits, state universities offered a chance to study while working. The University of Wisconsin, for instance, charged in-staters $120 (~$1,400) and out-of-staters $420 (~$5,400 today). For an in-stater earning a federal hourly minimum wage of between 75 cents ($1.00 after 1956), that tuition was perfectly affordable with a summer's worth of work. Even at elite schools like the University of Pennsylvania, which charged $600, it was possible to reduce one's obligation considerably by working part-time.

Women's enrollment declined as they opted to marry early and start families, per a study by University of Colorado Prof. Murat Iyigun. Presumably anticipating greater earning power that would allow them to stay home, however, they also worked to fund their husbands' education. And this is not just a theory – universities even invited the wives of graduates to a "PhT" ceremony – shorthand for "putting him through."

Scrutinizing teachers' politics

Today, asking an employee or potential hire about political views is fodder for a discrimination lawsuit. In the 1950s, however, amid the Red Scare and fear of communist infiltration in schools, it was not only permitted but encouraged if employees showed signs of sympathy for socialism or communism.

As noted in Stuart Foster's "Red Alert!," published in the journal "Education and Culture," public schools were considered breeding grounds for communism amid a growing American culture war. There were integrationists (often accused of being communists) vs. segregationists, advocates of rote learning against advocates of "new" methods, supporters of patriotic education vs. dissenters, etc.

The conflicts and flurry of back-and-forth accusations resulted in teachers being investigated and fired from their jobs. The 1953 Philadelphia purge was one such example, with 32 teachers suspended over alleged ties to the American Communist Party. Such charges became criminal matters with the 1954 Communist Control Act, so the stakes were pretty high for accused teachers.

The National Education Association responded by closing ranks around teachers. The organization explicitly declared itself anti-communist and established the Defense Commission. This body presented itself as defending teachers from "red scare propaganda" and "witch hunters" who sought to undermine America's educational future. It also distributed literature for public consumption and engaged in public relations campaigns with Congress and prominent members of American society who supported the commission's mission. Overall, the commission was able to insulate teachers from the worst of the Red Scare, but as Philadelphia showed, it could only do so much when facing the full might of the U.S. government.

Special ed was virtually non-existent in public schools

Special education and separate schools have existed in the United States since the 19th century for blind, deaf, and cognitively impaired children. As compulsory education laws became the norm and public school enrollment increased in the 1930s onward, however, children with special needs fell by the wayside.

By the 1950s, conformity in education was emphasized (although not the norm in practice), and there was not much room for curricula tailored to individuals or groups in need. As a result, children with disabilities, cognitive and otherwise, could be denied access to public schools by state law. When children with special needs did end up in public schools, they underperformed. Gambino family underboss Salvatore "Sammy the Bull" Gravano, for instance, had dyslexia (via The Patch), recalling, "People would ask me to read something and I couldn't. I would get a blank piece of paper, scribble on it." Gravano told the Jordan Harbinger Show that dyslexia was his biggest challenge because people believed he was "stupid." Humiliated at school and with few prospects, he turned to crime – a frequent outcome for such children.

The situation improved in the 1960s, thanks to President John F. Kennedy, whose support of special education stemmed from his sister Rosemary's cognitive impairment. In 1963, he signed the Maternal and Child Health and Mental Retardation Planning Bill, which increased federal funds for special needs programs and facilities. Disabled children could be "victims of fate," Kennedy said, but a country as rich as the U.S. had no excuse to neglect them.

Separate schooling tracks

Today, the focus in American schools is overwhelmingly on college preparedness. Classes like shop and home economics, once mandatory for large swathes of the population, have either been cut or demoted to electives. This has produced concerns that the U.S. is neglecting students who are not interested in college, denying them crucial skills that could allow them to go straight into the workforce or trade school.

In the 1950s, however, there was career tracking, which separated students based on whether they were considered college-bound. The system was simple: students who excelled in the traditional subjects (Latin/Greek, literature, math, and hard sciences) were put into college preparatory schools. Those who did not exhibit such aptitude were put into schools, vocational schools, whose academic curricula were more basic, but also stressed mandatory shop (boys) and home economics classes (girls). In shop, boys were exposed to a variety of trades, including woodworking and metalworking. Although the classes did not prepare them to immediate become tradesmen, the skills were usually enough for them to get apprenticeships straight out of high school. Girls were taught domestic skills to become homemakers, in keeping with the 1950s ideal of marrying early.

While the system worked insofar as it ensured all students had opportunities to explore options besides college, it was criticized as hampering social mobility. Students who were tracked into the non-collegiate track were often from poorer households. The work track became considered the "remedial" track, per Forbes, and it was gradually cut in favor of today's system which favors college preparedness.