What Life Was Like As A Soldier In The Vietnam War

"War is hell" declares the handwritten slogan on a young GI's helmet in one of many famous photos of the Vietnam War. And after seeing the images of the Vietnam War on television, after seeing the pictures taken by war correspondents, and after hearing accounts of war atrocities, most of the American pubic in the 1960s was inclined to agree. The seemingly endless war, fought by American GIs thousands of miles away, had lost whatever sheen it might have had in 1955, when Americans at the height of the Cold War, committed to the Western ideals of freedom and democracy, were determined to stop the spread of communism in Asia.

That idealism faded away as the war progressed, as the U.S. sent more troops, more resources, and more money overseas, as more and more young American men failed to come home in one piece. And they were young men. The average age of a U.S. soldier dropped from 26 in World War II to just 19, not even old enough to vote at the time. Here's what life was like for U.S. soldiers in the Vietnam War.

The draft was a big deal during the Vietnam War

Of course, whether they could vote or not, the U.S. government viewed these men as potential soldiers the minute they turned 18 and became eligible for the draft. The Selective Service was organized as a random lottery in which men's birthdays were assigned a lottery number between 1 and 365, one for each day of the year. However, because of the way the draft was set up, men assigned the lowest numbers were more likely to be drafted than those with higher numbers. In 1969, doctoral student David Stodolsky recognized the problem and sued the government.

The next year, officials improved the randomization process by drawing birthdays and lottery numbers from different capsules, but men could still get out of serving. The most common loophole was the college student deferment policy, which excused any man enrolled in college or graduate school. Medical professionals could also declare someone "unfit for service" for medical conditions ranging from ulcers to anemia. Upper-class men could afford to stay enrolled in university or get a doctor's note from a hometown physician to obtain a get-out-jail-free card that poorer men couldn't access. According to James Fallows, these loopholes "were designed to allot American talent in productive way," but resulted in "the starkest class division in American military service since the days of purchased draft deferments in the Civil War."

Race relations were bad for soldiers in the Vietnam War

The draft lottery proved to be unfair in another significant way. According to the New York Times, African Americans were drafted at a disproportionately higher rate than whites, representing more than 16% of all draftees and 23% of all combat troops, despite being only 11% of the civilian population in 1967. The draft wasn't the only problem. Vietnam was the first major U.S. war in which black and white soldiers were fully integrated, but fully integrated did not mean fully equal. Black soldiers complained they were unfairly assigned worse details and that they received more frequent punishments and fewer promotions than their white counterparts. Only 2% of officers were black.

Still, tensions between black and white soldiers were low at the onset of the war. Wallace Terry, a black war correspondent for Time, described seeing "thousands of Americans who found their common humanity on the front, where they shared the last drop of water, where they gave their lives for each other. ... The Armed Forces during the war and even today is the most successfully integrated institution in our society." But after Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination, the racial violence that had been bubbling up in cities across America finally reached Vietnam. Upon hearing the news of MLK's death, some white soldiers paraded around the base at Cam Ranh Bay in KKK robes, openly cheering the news. Unsurprisingly, this did not sit well with black soldiers, and discord only worsened as the war dragged on.

REMFs had it relatively easy

Regardless of race, some men chose to enlist in the Vietnam War before their numbers came up, knowing they would be assigned better details if they went voluntarily. Instead of being stationed on the front lines, they might be assigned a support detail on one of the rear bases. Soldiers who landed mechanical or logistical support roles had a much different experience in the war than those in combat zones. Somewhat pejoratively called REMFs ("Rear Echelon Mother F*ckers") these soldiers had a comparatively cushy experience in Vietnam.

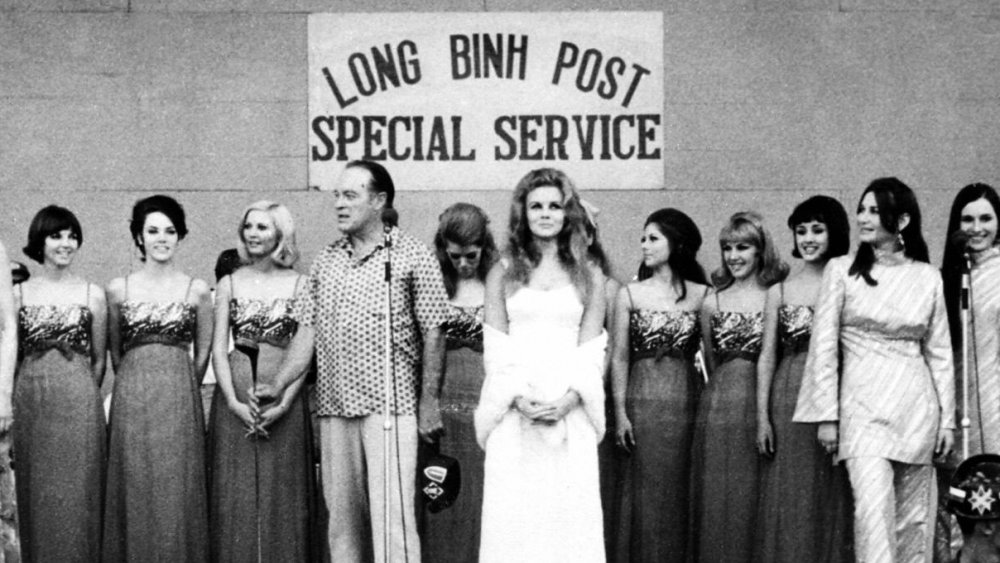

About 75% of the 2.5 million soldiers fighting in Vietnam worked in support roles as clerks far away from the front lines. These men had access to all the luxuries of home, including getting to sleep in a bed, eating hot meals, drinking at bars, and shopping at a well-stocked commissary. In some cases, the luxuries even exceeded the ones the men would have gotten at home. The army headquarters at Long Binh boasted such amenities as a go-kart track, swimming pools, weight rooms, mini golf, an archery range, an amphitheater that frequently hosted live shows, and even a brothel — officially unsanctioned but well-trafficked.

Life was tough for combat soldiers in Vietnam

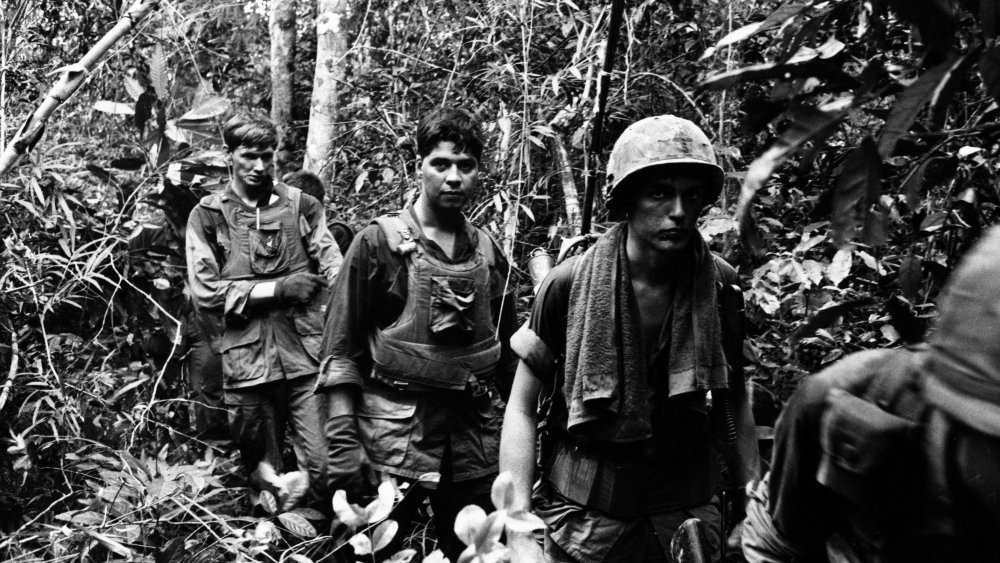

Most grunts passed through the rear bases on their way into or out of the field, but they didn't stay long. They had their own jobs to do. Officially, their goal was to take back South Vietnam from the communists, find and eradicate the Viet Cong, and secure the hearts and minds of the locals. But mostly what they did was walk. They walked for days and weeks at a time, patrolling the land for Viet Cong guerrilla fighters or members of the North Vietnamese Army. They walked without a bath, a hot meal, or a good night's sleep. They walked until they got jungle rot, infected skin lesions that came from "humping the boonies" too long without adequate footwear. They walked with heavy rucksacks, carrying everything they would need to survive in the difficult terrain. They carried food rations, flak jackets, rifles and ammunition. They carried the fear that at any moment, a surprise attack could kill them. Most crucially, they carried mosquito repellent and dry socks.

Their goal was to locate and defeat the Viet Cong, but often it felt like there was no real goal except providing human bait to provoke the guerrilla fighters into revealing their positions. The Viet Cong were frequently one step ahead, hiding in the trees or blending in with the locals, so the villages were never really secured, and the locations of the guerrilla fighters remained uncertain. So the grunts kept walking.

The environment was deadly for a Vietnam War soldier

"The land itself could kill you," remembered Tim O'Brien. Yes, the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army were trying to kill them. But so were the swarms of mosquitoes that spread dengue fever throughout camps, and with the 30 different kinds of venomous snakes whose bites would prove to be fatal. And if the land wasn't actively killing them, it was making them miserable. Morale was understandably low during monsoon season, for example, when heavy rains would drench the soldiers and flood the rice paddies for the better part of six months.

And when it wasn't raining, it was hot and humid. Between the rain and the sweat the grunts were never completely dry. If they weren't miserably wet or miserably hot, they were miserable hacking through the jungle brush and elephant grass with leaves so dense and so sharp they drew blood. Soldiers also had their blood sucked by leeches who made their homes in the rice paddies.

Combat was awful

The land was a dangerous enemy by itself, but its biggest threat was the dangers it concealed. Whether in the thick of the jungle or deep in the rice paddies, the landscape was strange to the U.S. soldiers, but it was familiar to the Viet Cong, who expertly hid themselves in the land. American troops, with their vastly superior firepower, had the upper hand face to face, but the Viet Cong deliberately avoided large-scale conflicts where they could be outgunned. Instead, they waited in the vegetation for nightfall or awful weather or other convenient moments. They hid landmines and booby traps to inflict casualties and heighten the fear American GIs felt with every step. The Americans fought back with bombing campaigns that laid waste to villages, and sprayed napalm that burned the skin off fighters and civilians alike. They used Agent Orange to raze the tropical foliage, destroying the environment that the Vietnamese were using against them. But they ultimately couldn't defeat the guerrilla fighters. For the Americans, every casualty, every dollar spent, and every anti-war protest back home chipped away at the conviction that this could ever be a winnable war.

Soldiers had a mixed record with the Vietnamese civilians

In a war where morale was already weakened by unclear objectives and uncertain outcomes, unfriendly encounters with the Vietnamese civilians they were ostensibly liberating only made matters worse. Although the official goal of the war was to prevent communism from spreading into South Vietnam, American soldiers felt they had reason to mistrust everyone, North and South Vietnamese alike. Viet Cong were adept at blending in, sometimes taking cover in villages. American troops didn't know if the villagers were aiding the Viet Cong, harboring enemies, or laying traps that could kill American troops. Civilian casualties were common, and many local villages were disrupted, if not outright destroyed, by the arrival of U.S. soldiers, so it's no surprise that locals often viewed American soldiers with distrust and hostility.

Soldiers were tasked with the job of winning over the hearts and minds of the local Vietnamese population, convincing them that Western liberation from communist forces would improve their lives. However, infantrymen whose successes were determined by enemy body count were untrained and ill-equipped to make the cultural advances that would win people over. As time went on, civilian casualties continued, American soldiers grew increasingly frustrated with the locals' reluctance to help, and suspicion and mistrust increased on both sides.

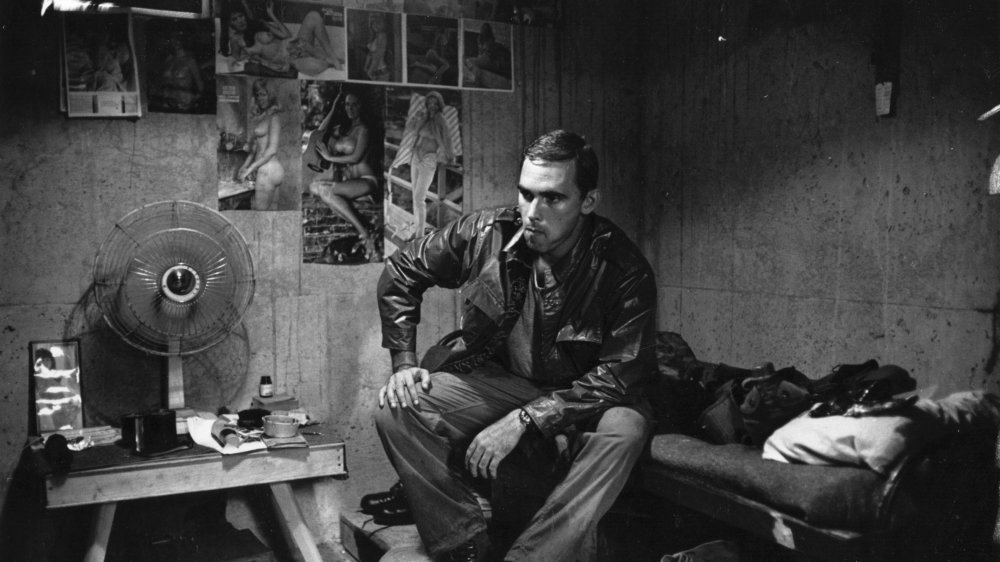

Vietnam War soldiers also struggled with boredom

When the grunts weren't walking or being shot at or eyeing the locals with suspicion, they were waiting around for something to happen. Even in the midst of an active, bloody war, downtime was a frequent, if not always welcome, occurrence. Even the front lines were punctuated with periods of inaction. At times, Vietnam resembled "a hated, dreary struggle" that dragged on and on with no end in sight. Since large-scale warfare was rare, soldiers could go for weeks without encountering enemy forces, but far from being a respite, the quiet only heightened the tension. Soldiers knew there would be another surprise attack, they just didn't know when, and the not-knowing could drive them crazy. But in the meantime, there were hours and even days where there were no Viet Cong to be found, no fights, and nothing to distract them from the monotony. There were booze and drugs if they could get them, but for the most part, the hours ticked by, only breeding more anxiety.

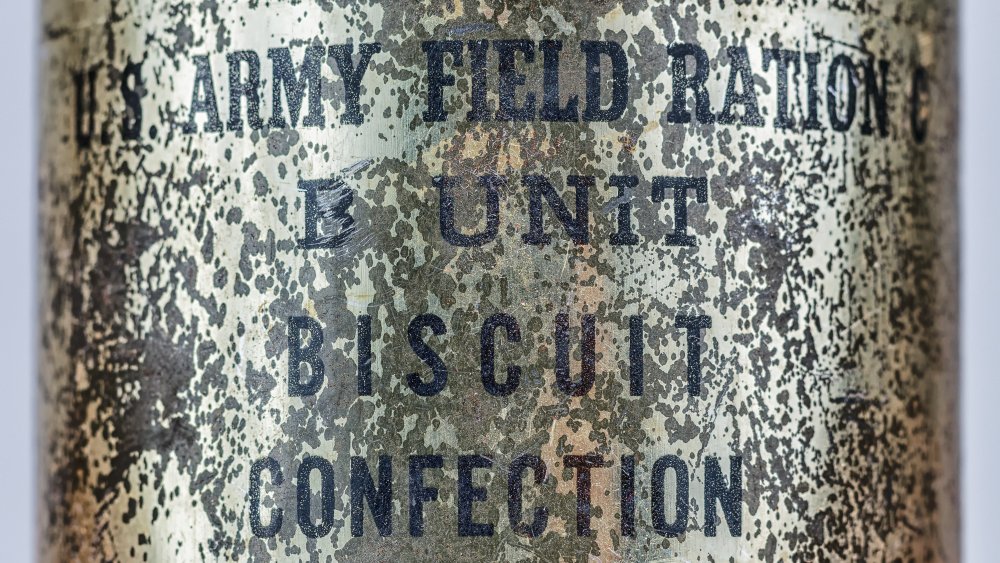

Vietnam War rations were pretty bad

One thing soldiers didn't have to take their mind off things — the one thing that was almost impossible to come by — was a good, hot meal. Rations were dismal. At first, there were C-rations, ready-made wet meals served in cans, but those proved to be too heavy for special operations that required long treks on foot. Instead, the military developed long range patrol rations to take their place. LRPs were freeze-dried, dehydrated field rations that came in waterproof bags and were much lighter than the bulky cans soldiers had previously carried. The taste, however, left a lot to be desired. The rations were commonly compared to wet dog food, and the only way to heat them up in the field was by resorting to potentially dangerous explosives. Larry Michael, a former infantryman in Vietnam, reported that "if you really wanted it hot, you broke up a claymore mine ... took the C-4 (explosive) out, lit it and then warmed it up. But that's the only way you had a hot meal."

Recreation for Vietnam War soldiers

There was a glimmer of light on the horizon for bored, anxious, hungry soldiers in the field, and that light was their annual R&R. Soldiers were permitted six days and six nights of leave during their one year tour of duty. On the military's dime, soldiers could fly to any number of exotic locales in search of beaches, bars, and a good time. Hawaii was the most popular destination for soldiers who had families, since dependents were allowed to meet them in Honolulu and spend some time with them. Soldiers on leave with their wives and children made up a large chunk of Hawaii's hotel room traffic during the Vietnam War.

Places like the Philippines, Hong Kong, and Thailand were popular among the younger crowd who wanted to have less family-friendly fun. The influx of American tourists was a catalyst for Bangkok's massive growth in the 1960s, as the construction, finance, air, retail, and hotel industries boomed to accommodate the influx of soldiers looking for a good time. While drinks and companionship were always a draw, recreational drug use skyrocketed during the Vietnam War. Marijuana was cheap and easy to come by, but commanders were more concerned with the surge of heroin usage among enlisted men, which reached epidemic levels by 1971.

Drug use was rampant during the Vietnam War

If they wanted recreational drugs, most Vietnam War soldiers didn't have to go farther than their military doctor. Over the course of the Vietnam War, the military prescribed more than 225 million tablets of speed to U.S. soldiers, earning itself the title of American's first "pharmacological war." Troops were supplied with so-called "pep pills," their nickname for Dexedrine, an amphetamine that was double the strength of the stimulants the military had prescribed in previous wars. In addition to speed, officials also supplied soldiers with painkillers and steroids to increase their stamina, strength, and aggression on long-range missions. Military personnel also liberally prescribed antipsychotics such as Thorazine, which numbed the psychologically traumatic effects of combat.

On the surface, it appeared to have worked. Reported cases of mental breakdowns among troops dropped to just 1% during the Vietnam War compared to 10% during World War II. But the success was short-lived. While the symptoms of trauma were suppressed in the short term, the effect was something like putting a Band-Aid on a broken leg. Repressing the negative mental effects of combat only worsened their impact when they finally surfaced. The use of pharmaceuticals to artificially suppress combat trauma may have contributed to the explosion of post-traumatic stress disorder cases among Vietnam veterans after the war.

When soldiers returned home from the Vietnam War

After returning home, Vietnam War veterans experienced PTSD in record numbers. According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, about 30% of soldiers who saw combat in Vietnam experienced PTSD in their lifetime. Drug use had taken its toll on troops. The New York Times described heroin addiction as "the Army's last great tragedy in Vietnam." By 1971, 10-15% of lower-ranking troops were returning home as addicts, and over 1,000 were returning as criminals, having been charged with heroin-related crimes. Others died of overdoses before they could even make it back.

That's not to say the drugs deserved all the blame for the difficulty veterans faced after returning home. Far from returning as conquering heroes, they returned home to a stagnating economy, scarce GI benefits, little government support, and an unwelcoming populace. Veterans encountered unprecedented levels of hostility from a public that had long objected to U.S. involvement in Vietnam. They had to bear the dual burden of guilt for the brutal atrocities that had been committed and shame for the failure to bring home an American victory after such a drawn-out war. Both the government that had drafted them and the public that resented their participation in Vietnam abandoned the men who had served their country, leaving them few options to cope with the aftermath of all the trauma they had experienced and caused.