The Biggest Theories Why Serial Killer Jack The Ripper Was Never Caught

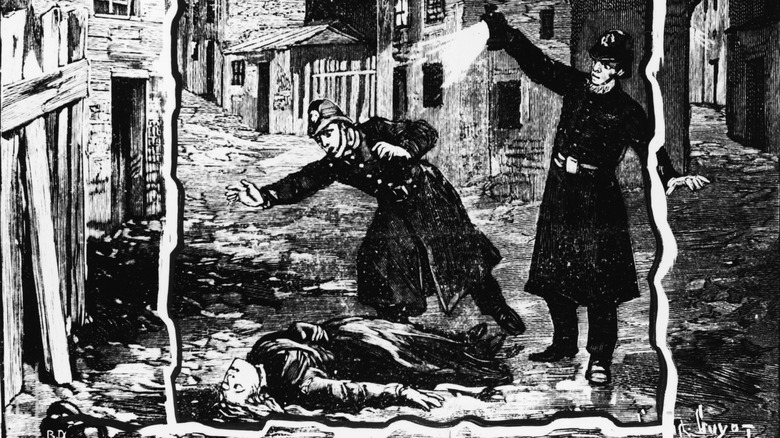

Few historical true crime stories have attracted as much undying interest as the case of Jack the Ripper. A brutal serial killer who operated alone in the streets of Victorian London in 1888, he is believed to have murdered at least five women who were sex workers in the city's impoverished East End district of Whitechapel. The Ripper's pseudonym comes from his cutting his victim's throats and subsequent mutilation of their bodies, details of which were often recounted in grisly detail in the periodicals of the day.

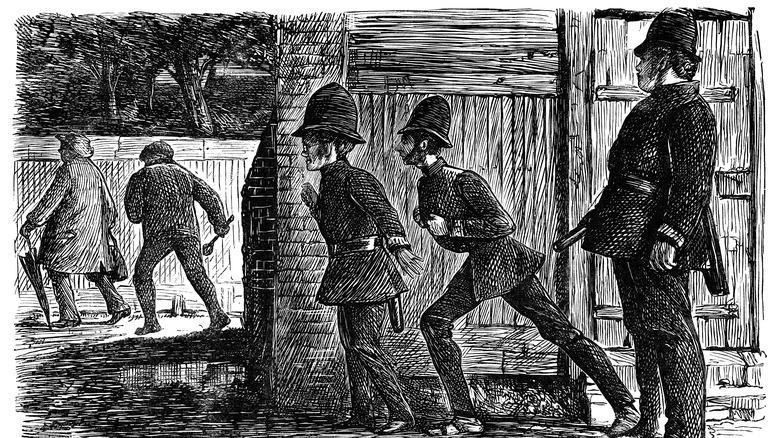

Jack the Ripper's crimes sent a wave of fear throughout the bustling city, with several more murders attributed to the serial killer before the turn of the century. The crimes led to a major police operation, in which investigators combed the streets and interviewed countless people to try to get to the bottom of the notorious murderer's true identity and bring him to justice.

But despite several figures being identified as Jack the Ripper by investigators and enthusiasts in the years that followed, more than a century on no-one has ever been positively identified as the killer of the "canonical five" victims, the first of which was Mary Ann Nichols, followed by Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly. Why? Here are five major factors that led to London's most notorious serial killer disappearing into the fog forever.

The police didn't possess the neccessary expertise

Even during Jack the Ripper's reign of terror over the East End of London, there was a great deal of dismay concerning the Metropolitan Police Force's inability to apprehend him. But the public's turning against the police wasn't simply a symptom of the city's panic. In fact, the police investigating the serial killer were so useless that they have been identified by numerous sources as the primary reason why Jack the Ripper was never brought to justice. In today's true crime-drenched world, the idea that police occasionally bungle their investigation despite an abundance of resources — they may miss key pieces of evidence or fail to properly investigate an important suspect — is well established. But back in the 1880s, police faced many more challenges due to a lack of technology and expertise that could be used to catch dangerous criminals.

DNA testing and forensics had not been developed, but despite the ingenuities that many associate with fictional Victorian figures like Sherlock Holmes, techniques as rudimentary as fingerprinting had yet to be developed to any useful degree, being only deployed professionally in the early 1900s. Similarly, they had no policy with regard to protecting crime scenes, and with all of these murders taking place in the side streets of busy slums, the murder locations were almost instantly compromised making it impossible to gather what might have been valuable pieces of evidence.

They didn't truly understand the murders

Whitechapel was known for a great deal of gang activity in the 1880s, and for weeks following the Ripper's first murder, the police were convinced that the killings were gang-related. The concept of a sadistic serial murderer was little known in the 19th century, with only 13 murders in the whole city the previous year, according to London Walks.

As explained in Donald Rumbelow's "Jack the Ripper: The Compete Casebook," the last thing that police — or society as a whole — expected was that systematic murders could be of a sexual nature. There had only been a handful of such sex crimes that were known to educated people, and those had taken place across the whole of Europe over the course of several centuries. Their understanding of violence in general instead saw it as a product of economic instability — robberies or muggings — or the actions of drunkards. That the Ripper had what we would now call a "modus operandi" or M.O. was not something investigators would bank on and exploit in their search, nor had they any sense of the kind of psychological profile that could be capable of such murders.

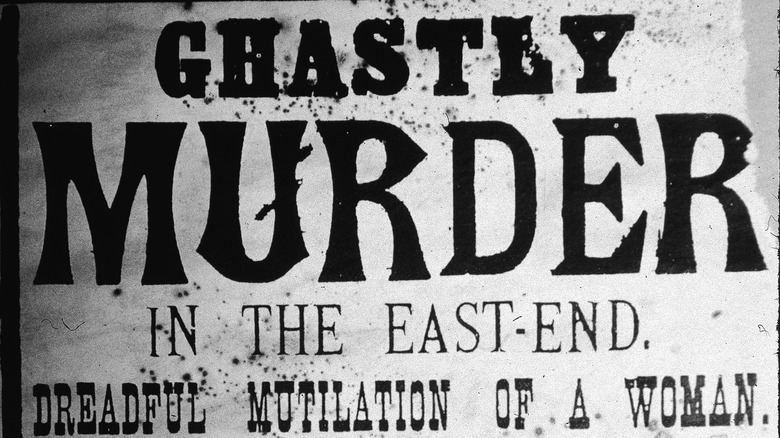

The papers sensationalized the story

Victorian England was a society in the thrall of daily newspapers and other periodicals that were read by all literate people to stay on top of the latest goings on. And then, as now, it was well known that readers were especially receptive to lurid stories involving real-life crime. A sensationalized form of often fictitious reportage, the "penny dreadfuls," told crime stories through captions and cartoons that were intended to shock, scare, and appall their readership.

It is no surprise then that the story of Jack the Ripper became the biggest story of the day. Unfortunately, it was also ripe for sensationalization, with the largely unregulated dailies reporting a great deal of misinformation circulated by journalists who were more concerned with delivering a big story than a possibly more prosaic version of the truth. As the History Press notes, the false reporting — which would include fabricated witness accounts — would wrongfoot both the police and other witnesses, leading to a panicked city where nobody was sure of the facts of the case. To make matters worse, there was also an ongoing rift between the police and the press, with officers barred from talking to journalists, meaning that there was no alignment in terms of sharing information either between the two factions or with the wider public.

Unreliable witnesses

Unfortunately, though the city of London was drifting into confusion concerning the exact facts of the Jack the Ripper case, much of the police's investigations depended on the testimony of local people. As the tale of Jack the Ripper took on a mythic status, it became increasingly difficult for investigators to establish the truth when it came to sightings of potential suspects.

To compound issues, Whitechapel was densely populated with many large families, with groups of children often circulating in the streets. As a result, apparent sightings of Jack the Ripper often came through word of mouth or were distorted by lurid rumors about the killer that were already in the air.

Though "Ripperologists" are split over whether the police were despised or respected by the general populace at the time of the Jack the Ripper murders, there is certainly evidence that investigators had trouble connecting with locals, some of whom were involved in crime as a result of their poverty. Meanwhile, some of those who may have been useful witnesses were migrants who spoke little or no English at a time when translation was not readily available.

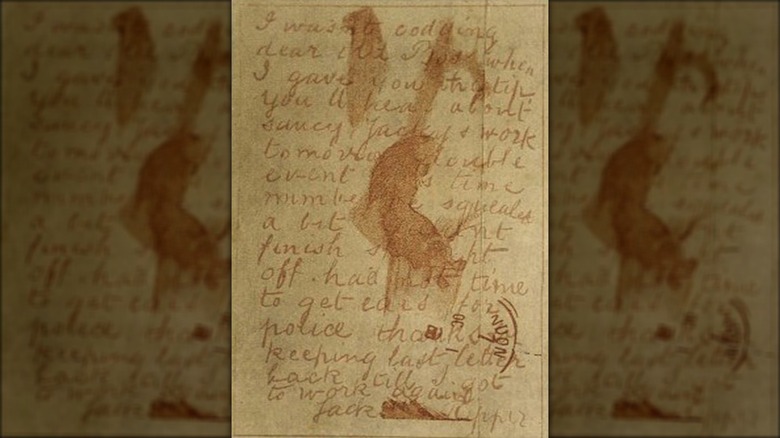

A deluge of letters -- and impostors

With no telephones yet available in Victorian England — at the time, there weren't even electric street lights — another factor that may have helped Jack the Ripper to strike with anonymity — letter writing was the chief mode of communication among both regular people and the professional classes. Letters allowed people to communicate with both the press and the police with potential clues and pieces of useful information that would help identify the killer.

However, the mail also became a major source of confusion and red herrings, with the police reportedly contending with hundreds of pieces of unexpected correspondence concerning the case. Things really came to a head in late September and early October 1888, when London's Central News Agency received a letter postcard — the latter of which was seemingly smeared with blood — purporting to be from Jack the Ripper, who promised to keep on killing until he was caught. The correspondence has never been confirmed as truly being the killer's, though it generated a great deal of copycat letters that muddled the investigation further.

Things took yet another dark turn when the head of a vigilante group, the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, received a letter from the apparent killer that arrived with half of a human kidney. Though some investigators have since claimed that some of these deliveries may have come from the real Jack the Ripper, none have ever led to the killer being positively identified, and some believe they may have been the work of journalists keen to keep the lucrative story in the public eye, per Smithsonian.