'80s Grammy Winners Who Fell Victim To The Best New Artist Curse

According to music industry lore, there's a curse associated with the Grammy Award for best new artist. Many groups from the 1980s in particular experienced such rapid career downturns that it appears they were hit by the same fate that took down so many best new artist honorees before and after their era. The real reason why so many once-promising artists fizzle out is probably because it's terribly stressful to follow up an early success and because the public moves on from the hot new thing in music very quickly. And so, the history of the Grammys is littered with the memory of one-hit wonders who vanished after winning the Grammy Award for best new artist.

For proof of a so-called curse, look to forgotten best new artist winners like The Swingle Sisters, Starland Vocal Band, and Shelby Lynne. (Pay no mind to the undeniable legends that won, like The Beatles and Mariah Carey — it's not a perfect theory.) Musicians affected by the best new artist curse are those that didn't enjoy much success past the early work that garnered Grammy attention or even after their trophy led to a boost in interest and sales. Or, groups that broke up or faded away in a hail of controversy — the kinds of things that seem to be triggered by the fickle finger of fate. Here are the '80s Grammy winners for best new artist that are possibly cursed.

Christopher Cross

Until Billie Eilish repeated the feat in 2020, the only artist in Grammy Awards history to win all four of the biggest prizes in one night was Christopher Cross. The warbly soft rock balladeer was intrinsically linked to the ultra-smooth and laid-back "yacht rock" sound that briefly took hold in the '70s and '80s. And at the 23rd Grammy Awards in 1981, Cross won best new artist, album of the year for his self-titled debut LP, and record of the year and song of the year for "Sailing," which spent a week at No. 1 in the summer of 1980.

That Grammys triumph gave a significant boost to Cross's career and visibility. Along with "Sailing," he'd only enjoyed one other top 5 hit single, "Ride Like the Wind." After his industry coronation, Cross was asked to collaborate on "Arthur's Theme (Best That You Can Do)" from the film "Arthur," which won him a best original song prize at the 1982 Academy Awards. That tune also went to No. 1, and it was downhill from there. Cross' last entry in the Top 40, "Think of Laura," reached No. 9 in early 1984. By then, Cross's soft rock sound had fallen out of fashion, replaced with flashy, video-driven new wave hits. Sales of subsequent albums came nowhere near those of his first album, and after 1988's "Back of My Mind" missed the charts, Warner Bros. cut him from its roster of artists.

Men at Work

Injecting melancholy, humor, and seldom-heard instruments in the '80s (like flute and saxophone) into its quirky rock music, Men at Work shot out of Australia and to the top of the U.S. record charts. MTV and its early, experimental approach to music video programming are credited with the group's U.S. breakout. Two singles from the first Men at Work album, "Business as Usual," hit No. 1 on the Hot 100: "Who Can It Be Now?" and "Down Under" in 1982 and 1983, respectively.

Based on contemporary popularity, Men at Work was the correct nominee to win the best new artist award at the Grammys held in 1983. The group got to work quickly, releasing a follow-up album, "Cargo," right away in 1983, which generated the top 10 hits "Overkill" and "It's a Mistake." It looked like Men at Work was here to stay and would avoid any so-called "best new artist curse."

Fame and success proved exhausting and detrimental. After a long tour, the band spent most of 1984 on a break, during which time drummer Jerry Speiser and bassist John Rees quit. Bandleader Colin Hay hired session musicians to finish recording the next album, "Two Hearts," which sold only 500,000 copies, a fraction of the 9 million units moved by the first two LPs combined. Recognizing that the world had tired of its unique sound, Men at Work broke up, and Hay launched a mostly unnoticed solo career.

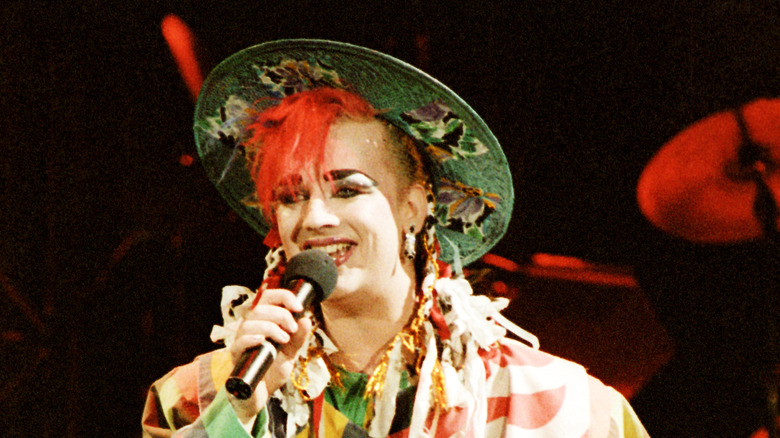

Culture Club

Not only a transformative force on music, Culture Club also made big gains for LGBTQ+ visibility, demonstrated the power of MTV, and impacted '80s fashion. The British new wave four-piece was led by quintessential 1980s celebrity Boy George, whose color-splashed, hat-topped, makeup-enhanced fashion choices were both daring and controversial for their gender-neutral and feminine elements. Perhaps most importantly, Boy George knew how to physically express the moody, complex emotional themes innate to Culture Club's pop-rock, which made its cinematic videos MTV smashes. The group was named the best new artist of 1983 at the 26th Grammy Awards following a strong and lengthy string of hits that included "Do You Really Want to Hurt Me," "I'll Tumble 4 Ya," "Karma Chameleon," "Church of the Poison Mind," and "Time (Clock of the Heart)."

Boosted by approval from the American music mainstream, Culture Club carried on through the mid-1980s, releasing two more albums, 1984's "Waking Up with the House on Fire" and 1986's "From Luxury to Heartache," and scoring hits with "It's a Miracle" and "The War Song." But then, the group fell apart, doomed by internal romantic tensions. Boy George and drummer Jon Moss had secretly been a couple for four years, but they split in 1985 amidst a stressful tour. The backstage fighting between the two became so verbally and physically abusive that it deeply troubled the rest of Culture Club, which broke up in 1986.

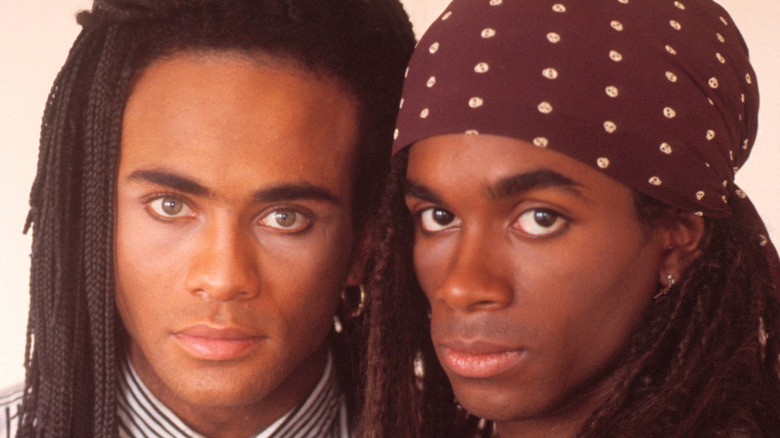

Milli Vanilli

Only once in history have the Grammy Awards rescinded a prize: The one for best new artist of 1989 given to dance-pop duo turned cursed pariahs Milli Vanilli. The act, consisting of Fab Morvan and Rob Pilatus, had made a huge splash with its initial run of hits: "Blame it on the Rain," "Girl I'm Gonna Miss You," and "Baby Don't Forget My Number" all reached No. 1, and "Girl You Know It's True" peaked at No. 2. The album that spawned all those hits, "Girl You Know It's True," sold 6 million copies before Milli Vanilli even won its Grammy.

But then Milli Vanilli's sins, or those of its handlers, were exposed. They revealed the messed-up truth about the 1980s music industry and culminated in one of the biggest scandals in pop history — one that would destroy the careers of Morvan and Pilatus. A 1989 performance in Connecticut went awry after a backing track playback device failed, revealing that Milli Vanilli had been lip-syncing. Afterward, speculation arose that perhaps the duo hadn't actually sung on its recordings either — Morvan and Pilatus spoke with accents not heard on their hits. In November 1990, Milli Vanilli's producer, Frank Farian, admitted to a reporter that he'd actually recorded a few otherwise unknown session singers — Morvan and Pilatus were merely hired actors and dancers playing the part of Milli Vanilli. Days later, the duo returned their Grammy at a press conference.