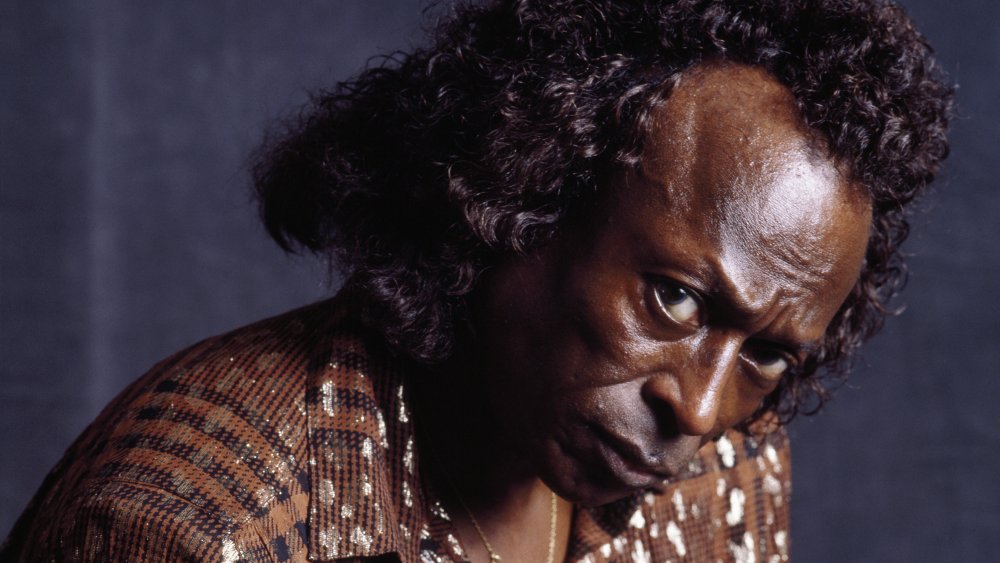

The Truth About Miles Davis's Troubled Life

His mother was a music teacher, but it was his father, a dental surgeon, who introduced 13-year-old Miles Davis to the trumpet. He was playing professionally by the time he was in high school, and when but 17 years old was invited on-stage by Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker — two jazz legends — to fill in for their ill bandmate. A year later, according to Biography, 18-year-old Miles was heading for New York City's Juilliard School (then the Institute of Musical Art). He connected again with Parker and played bebop, a style of fast, improvisational performance that laid the foundations for modern jazz music. He dropped out of Juilliard to play. And play he did.

Davis truly revolutionized the performance of jazz in the 1940s. As Encyclopedia Britannica tells it, "his melodic style was direct and unornamented, based on quarter notes and rich with inflections." While he continued to play with Parker, he also formed his own nine-piece jazz ensemble, featuring such non-traditional instruments as French horn and tuba. Their recordings were collected into the album Birth of the Cool, a landmark set of jazz performances that remain influential to this day. With the success also came temptation, in the form of heroin. Davis became addicted in the 1950s, but by 1954 had beaten it.

Davis overcame addiction to produce 'fierce beauty'

He continued to record and perform with an ever-shifting roster of musicians, and in 1969 recorded Bitches Brew, another departure, that set the stage of jazz fusion, combining elements of rock-and-roll and traditional jazz technique. Some people hated it. Some people loved it. It earned Davis a spot on the cover of Rolling Stone Magazine — the first jazz artist ever.

The year 1975 was the start of another rough personal time for Davis: he became addicted to cocaine and alcohol, leading to a five-year music hiatus. Drugs weren't his only fault; Davis wrote in his 1989 autobiography of physically abusing women, and his admiration for other men who kept women "in line." In its review of his book, The Atlantic characterizes his treatment of women as "contemptible." Further, says the review, "he accuses white jazz critics of having written approvingly" of other jazz artists "in an effort to deflect attention from him."

He was known to play with his back to his audience, and feuded publicly with fellow trumpeter Wynton Marsalis. Whatever his personal demons — and they were legion — he was given a Lifetime Achievement Grammy Award in 1990. In September 1991, Davis died, a victim of respiratory failure, pneumonia, and a stroke, after a lengthy hospitalization in Santa Monica, California, according to his New York Times obituary. Davis was 65. His final album, Do-Bop, was released in 1992. The Times said that his "lasting legacy to American music" was his "fierce beauty."