The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Louis Armstrong

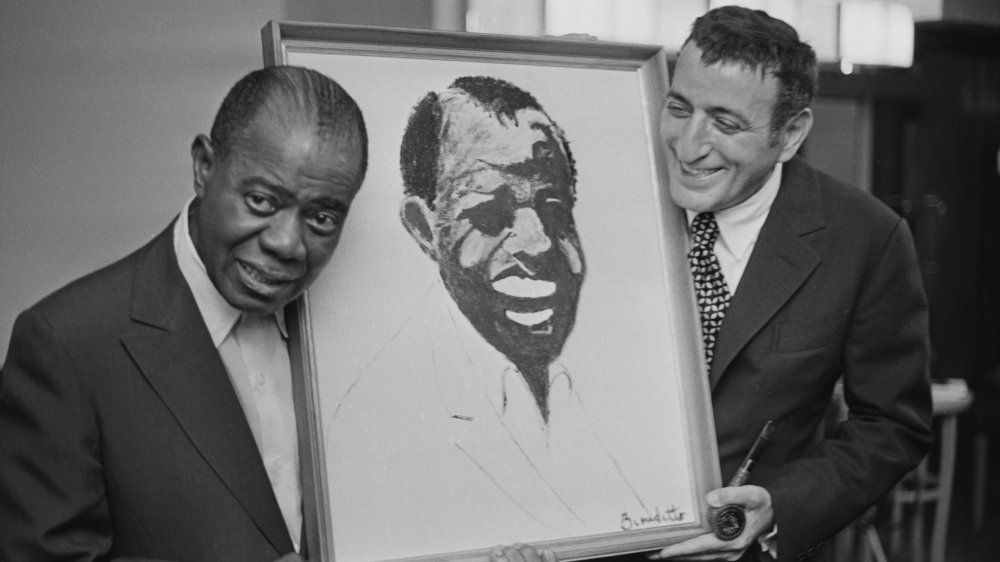

Every genre of music has those artists that change it forever. Just like rock-n-roll had Elvis and The Beatles, jazz had Louis Armstrong.

And even those who don't necessarily call themselves fans of jazz know his signature song: "What a Wonderful World." That actually came fairly late in his career, and before then, Armstrong had shaped the sound — and popularity — of jazz, beginning on the riverboats of the South, then hitting the nightclubs of Chicago, and then... the world.

But behind the career, the success, and the fame, there was tragedy. The man nicknamed Pops and Satchmo didn't have an easy life by any stretch of the imagination, and even as he was taking to the stage and wowing fans of all ages, classes, and races, he struggled. From his youth in New Orleans to the incredible toll performing took, from poverty and racism and even attempts on his life, here's the tragic tale of jazz's most famous musician.

Louis Armstrong was born on the wrong side of the tracks

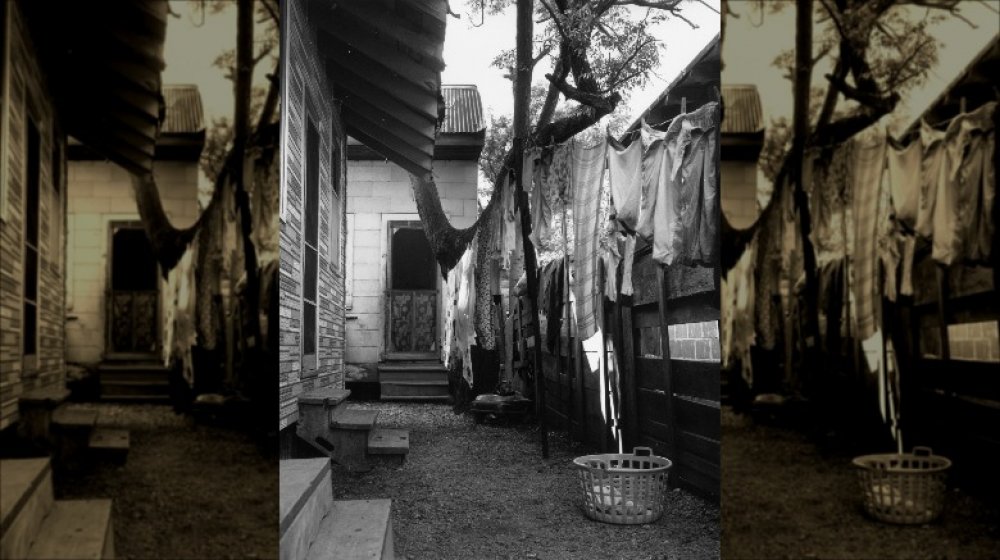

Louis Armstrong was born on August 4, 1901 (via Biography), and he grew up in an insanely tough neighborhood that was, at the time, called the Battlefield. Today, the National Park Service says it's mostly been redeveloped — it's where the Superdome is now — but at the time, it was known as the "colored red light district," filled with vaudeville theaters, brothels, saloons, and gambling dens. (Pictured is his childhood home.)

There's a lot of his early life that's up for debate, but much of it comes from a memoir he wrote as he was in his last years, staying at New York's Beth Israel Hospital. According to historian Dalton Anthony Jones (via the University of Michigan), the memoir sheds a tragic light on the man behind the famous smile.

History says that Armstrong's father abandoned his young family when he was just a child, and his mother — still a teenager herself — was occasionally forced into prostitution to support her children. Those children helped, too: Armstrong detailed abject poverty in his memoirs, describing how he and his sister would have to go into the better parts of town and scavenge through the dumpsters for food. The necessity of working meant that he had to drop out of school when he was in fifth grade. "But," he wrote, "we were happy."

Louis Armstrong had a childhood full of hard work

Louis Armstrong was just 6-years-old when he found work, alongside the children of a local Jewish family called the Karnofskys. He wrote (via the University of Michigan) that by 5 a.m. he was up and out on the street, collecting scrap metal, bones, rags, and bottles. Then, he'd accompany the family as they went through town with their peddler's wagon, playing a little tin horn to attract customers. And at night, he made other rounds — through the red light district, selling buckets of coal.

The hours were long and the days were spent in poverty, but he wrote about the kindness, too. The Karnofskys regularly invited him to dinner, he sang lullabies to their youngest baby, and remembered them for their "wonderful souls."

And it's also here, with this family, that he would later write about how they had first introduced him to the horn, and taught him to sing "with feeling." But the memoir is also complicated, says historian Dalton Anthony Jones. Even as he lauds the Jewish community that he found himself welcomed into, he condemned other black families struggling to build lives in post-emancipation South. He very clearly identified more with the Jewish families: History says that he regularly wore a Star of David in tribute to the Jewish family who had welcomed him into their home and their lives.

An arrest led a 9-year-old Louis Armstrong to music... maybe

There's much of Louis Armstrong's young life that's debated, or just a bit of a blur — remember, at the time, he was just another troubled kid living in a tough area of New Orleans. So, there's a few different stories about how he headed down the path of music. According to NOLA, the arrest record of a 9-year-old Armstrong surfaced recently. He — along with five others — were arrested in 1910 "for being dangerous and suspicious characters," and he was sent to the Colored Waifs Home. Strangely, the documents changed the story that Armstrong himself had long told, that he first went to the home in 1913, and was introduced to music while he was there.

It seems that his 1913 stint in the home was his second, when he was arrested for firing a gun into the air at a New Year's Eve parade. It was during this stay that the institution band's director took the young Armstrong under his wing and gave him a cornet. The rest was history... or, was it?

Jazziz stresses that music was all around him growing up, and Armstrong himself would later write (via the University of Michigan) that his first performances were part of his childhood job. In this version of the tale, he accompanied the Karnofskys in their peddler's wagon, and it was his job to blow a tin horn and attract customers. More than that, though, he taught himself how to play a tune, and would entertain the other children.

Louis Armstrong's lips paid a terrible price

Louis Armstrong was a lifelong musician, and he didn't just make that clear on the stage: according to The New York Times, he had told each one of his wives, "The horn comes first." It did, but he paid a price.

History says that the force with which he played meant that he regularly split his lips open, and it was during a 1930s European tour that he met Franz Schuritz, a trombonist who had also invented a salve called Ansatz-Creme. He was a long-time fan, lent his name to merchandising the creme, and on the eve of World War II, instructed his manager to buy him a stockpile worth hundreds of dollars.

That wasn't the end of his troubles, though. His lips were covered with such hard calluses that he regularly used a razor blade to remove the worst of the scar tissue, and today, he's given his name to a lip condition that's still common among trumpet players. It's called Satchmo Syndrome, and PRLog says it's a potentially career-ending injury that happens when lip muscles rupture. Armstrong himself had it happen, and was forced to put his playing on hold for a year while he recovered.

On why he kept so many clippings of articles written about him

As The New York Times says, Louis Armstrong wasn't just a jazz sensation, he was the first pop star of the recorded era. There's a lot of pressure that goes along with that and fortunately, throughout his career, he wrote hundreds and hundreds of pages of autobiographical stories, sent thousands of letters, and recorded himself on reel-to-reel tapes. The Louis Armstrong House Museum needed a $3 million grant to digitize it all, and there's something else in the collection too — he was a huge fan of scrapbooking, collecting newspaper clippings about himself, and making collages.

Ricky Ricardi, director of research collections at the aforementioned Louis Armstrong House, said that he spent decades making these scrapbooks because, "He was just completely aware of his importance and wanting to be in control of his own story." That was part of it — along with an ever-powerful desire to perform — but there was something else at work early on, too.

He started making scrapbooks when he was in his 20s, not long after he headed to Chicago, joined King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band, and started to get noticed. But still, he collected newspaper articles and compiled them in scrapbooks so that when he approached club owners for gigs, he had concrete proof that he was a legitimate musician.

Louis Armstrong had run-ins with the mob

The Mob Museum says that Prohibition, jazz, and the mob all went hand-in-hand. The mafia owned the clubs and made sure there was booze, and jazz musicians provided the perfect musical accompaniment to the evening's revelries. Strangely, Louis Armstrong and Al Capone arrived in Chicago just a few months apart (via The Chicago Tribune). Armstrong hit the streets there in 1922, and it was only a few years later that he left again, bound for New York.

But biographer Terry Teachout says (via the Express) that wasn't the end of the story. Armstrong was never buddy-buddy with the mob, but it was impossible to exist in 1920s Chicago without crossing their path a few times, and after making a name for himself in New York, he once again headed back to Chicago. It was 1931, and he was at a club called the Showboat when a hood named Frankie Foster pulled a gun on him and informed him he was playing in New York the following day.

Armstrong spent the next few years on the run, never staying in one place for too long and finally heading to Europe to wait for things to die down. They didn't — not exactly — and he ultimately threw in with the mob-connected Joe Glaser. Glaser ran nightclubs for Capone, and what developed was a mutually beneficial relationship: Glaser protected Armstrong, and Armstrong packed the house.

Louis Armstrong was arrested in 1931

Louis Armstrong biographer Thomas Brothers said (via The Penn Gazette) that by the 1930s, Armstrong was a "modern, sophisticated, Northern, well-paid musician," but at the same time, there were still things that he absolutely couldn't get away with... like sitting next to a white woman on a bus. It was 1931, and Armstrong and his band were in Memphis, Tennessee. He took a seat, and was promptly arrested... even though the woman in question was the wife of his manager.

And that's definitely not the end of the story. Armstrong — and his band, who were arrested along with him — spent the night in jail before going to the Peabody Hotel for a performance the following night. The audience was all white — and when he opened the show, he dedicated the first song to the Memphis Police Department. The song? "I'll Be Glad When You're Dead, You Rascal You."

He didn't just get away with it, the police department later thanked him for the on-stage mention. Oh, and those police officers? There were a few in the audience, and the ones that were, also happened to be members of the Ku Klux Klan. So, why did he not get arrested again? Armstrong always made sure to play a particular song, usually more than once during a set. It was called "When It's Sleepy Time Down South," and it was a romanticized anthem to the days of the slave-owning South.

One of Louis Armstrong's 1957 concerts was the target of a bomb attack

The 1950s were ripe with racial tensions, and in 1957, Louis Armstrong became a target. On February 20, the Desert Sun ran with this shocking headline: "Satchmo Bombed, But Not Scared."

He had been performing at Chilhowee Park in Knoxville, Tennessee, and it was just one of a long, 61-show tour. They were about halfway through, playing before a crowd of thousands, and the makeup of the audience seemed to support what the Pittsburgh Courier had claimed just a few years before (via Medium): "Racial harmony is at its best here." But, when they regained the stage after a short intermission, there was a deafening explosion so loud that some heard it five miles away.

Armstrong paused just long enough to tell the crowd, "That's all right, folks. That sounded like a drunk falling out of the balcony." He finished the show and later, saw the massive hole outside. Witnesses saw a car — lights off — drive past, and dynamite was hurled out the window. If they were trying to scare Armstrong, it didn't work. He later told reporters, "The horn don't dig those race troubles."

Louis Armstrong's trademark smile was surprisingly alienating

Louis Armstrong may have catapulted jazz to the mainstream and become immensely popular, but not everyone was a fan. Some of his most ardent detractors were, in fact, his fellow musicians. The problem? It started with that famous smile. Miles Davis had this to say about it (via The New York Times): "I loved the way Louis played trumpet, man, but I hated the way he had to grin to get over with some tired white folks."

The Times further explains that when Armstrong first took the stage, it was, well, a different time. His persona, they say, hearkened back to vaudeville, minstrel shows, and the cabarets of New Orleans, and as society progressed, that era faded into the past. At the same time, The New Yorker says Armstrong was very, very aware of the world he came from, and it left its mark. He once said in an Ebony interview, "I don't socialize with the top dogs of society after a dance or concert. These same society people may go around the corner and lynch a Negro."

Armstrong occupied an odd place in the world of civil rights. At the same time he served as a goodwill ambassador for the State Department and declared Eisenhower a "no guts," "two-faced" president when he first backed down from mandatory integration, contemporary journalists covering Armstrong's shows referred to him as a "racial cop-out." And Armstrong himself wrote, "I've got sense enough to know that I'm still Louis Armstrong — colored."

Louis Armstrong had a complicated relationship with race and his hometown

Dizzy Gillespie was just one of the performers who hated Louis Armstrong's stage persona — according to The Chicago Tribune, Gillespie once described him as promoting the "plantation image." But, this was also at the same time Armstrong took a firm — and oftentimes loud — stance against prejudice, from the stereotypes portrayed on the big and little screens, to what was happening in current events. Among those he condemned? Civil rights leaders like Josephine Baker, who he claimed were exploiting the current climate instead of trying to heal it.

Perhaps strangest of all was his relationship with his hometown of New Orleans. In 1955, the city banned integrated bands (via The New York Times). Armstrong — and his integrated band — refused to play there, and didn't return until the ban ended more than a decade later (via The New Yorker).

He explained to Ebony: "I can't even play in my own hometown, 'cause I've got white cats in the band. All I'd have to do is take all colored cats down there and I could make a million bucks. But to hell with the money. If we can't play down there like we play everywhere else we go, we don't play ... If my people don't dig me the way I am, I'm sorry."

Louis Armstrong's tour schedule contributed to his horrible health problems

In 1959, Louis Armstrong was on tour in Europe when his doctor was summoned to his room. He was unable to breathe, and the official story was that he had come down with a case of pneumonia. In reality, says historian Dalton Anthony Jones (via the University of Michigan), he had a severe heart attack after performing on a grueling, 2-shows-a-day tour that took him from Sweden to Egypt.

And it didn't slow him down. In just a few years, he was hospitalized with swelling in his right leg and varicose veins, symptoms of poor circulation and a heart condition that was steadily worsening. By 1964 — when he famously dislodged The Beatles from their spot on the top of the charts — his gallbladder, kidneys, and liver were failing. By the time he was convinced to head to the doctor in 1968, he was alternately gaunt or bloated, fluid filled his lungs, and he was having such difficulty breathing that he could barely speak. He was completely bedridden the following year, underwent emergency surgery, and — according to Biography — saw the death of longtime manager Joe Glaser.

Still, he kept performing... albeit briefly. After performing in Las Vegas and at New York's Waldorf-Astoria, he had another heart attack. Two months later he returned home, promised to take the stage again, and passed away in his sleep on July 6, 1971.

Louis Armstrong had a secret daughter

For years, biographers said that Louis Armstrong had died without leaving children behind. That's changed — decades after his death — with a shocking declaration from a woman named Sharon Preston-Folta. According to The New York Times, historians had known for a while that he had actually had a child — not by any of his wives, but by Lucille Preston, a dancer he was having an affair with. And Armstrong — who wrote a lot — left behind detailed letters specifying how they were to be cared for (he sent them monthly checks, bought them a house, and paid a huge portion of her college expenses), and he also went into way too much detail about the instant "that cute little baby girl was made."

The tale was a heartbreaking one that predictably, didn't have a happy ending. Sharon was born in 1955, and Armstrong's relationship didn't completely fall apart with her mother until 1967. By then, she'd had enough — after years of back-and-forth, she had finally demanded to know when Armstrong was going to marry her. His response — "Never!" — was the end of their relationship, although the financial support continued until his death. In one of his final letters, he wrote, "Sharon may not realize now what I mean to her & doing for her. But I am sure as she matures she'll Dig Pops as the man who'll be loving her until the day he dies, or she dies. That's sincerity and from the heart stuff."