The Fascinating Life Of The Man Who Created The Twilight Zone

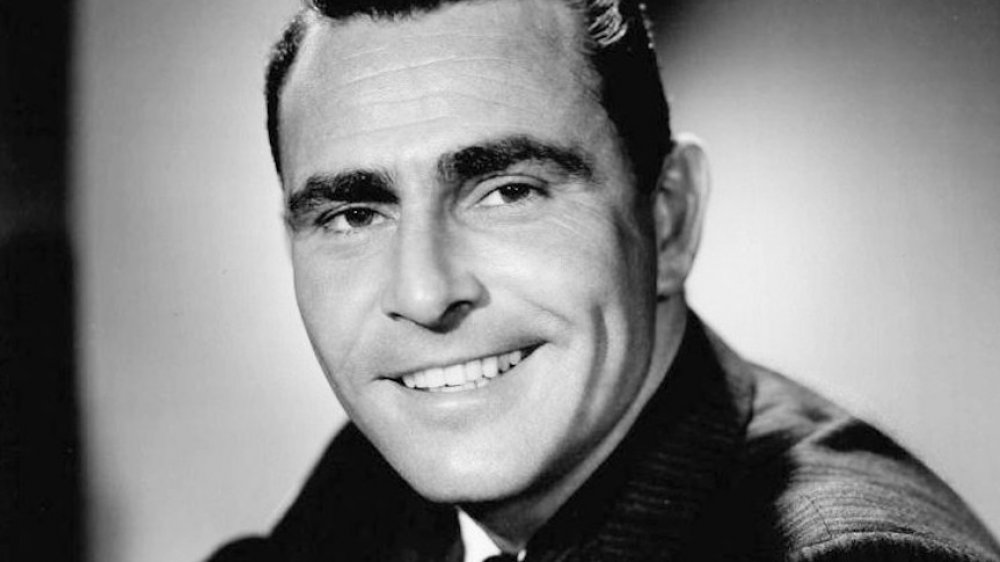

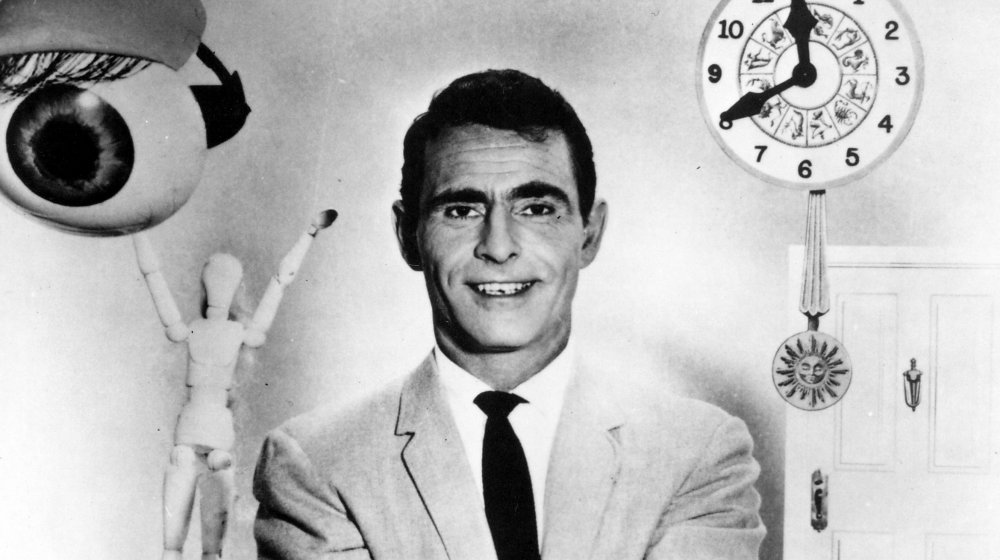

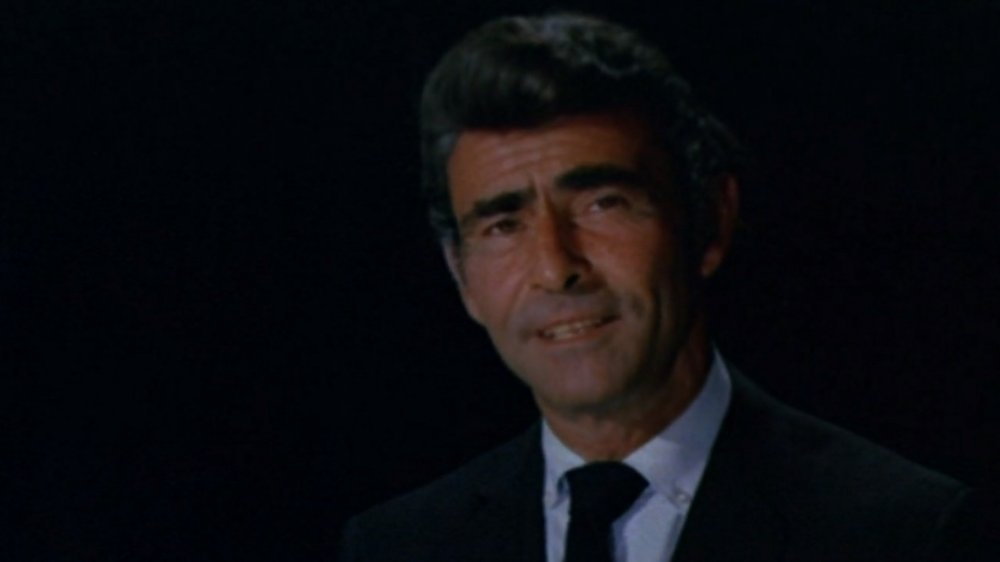

He's been called television's last angry man. With six primetime Emmys, three Hugo Awards, and the first Peabody Award ever awarded for TV writing to his credit, he remains the most honored writer in TV history over 40 years since his tragic passing. Yet, his life was often a pyrrhic battle against censorship, corporate influence, and social injustice. A visionary and an icon, he was Rod Serling, creator of The Twilight Zone.

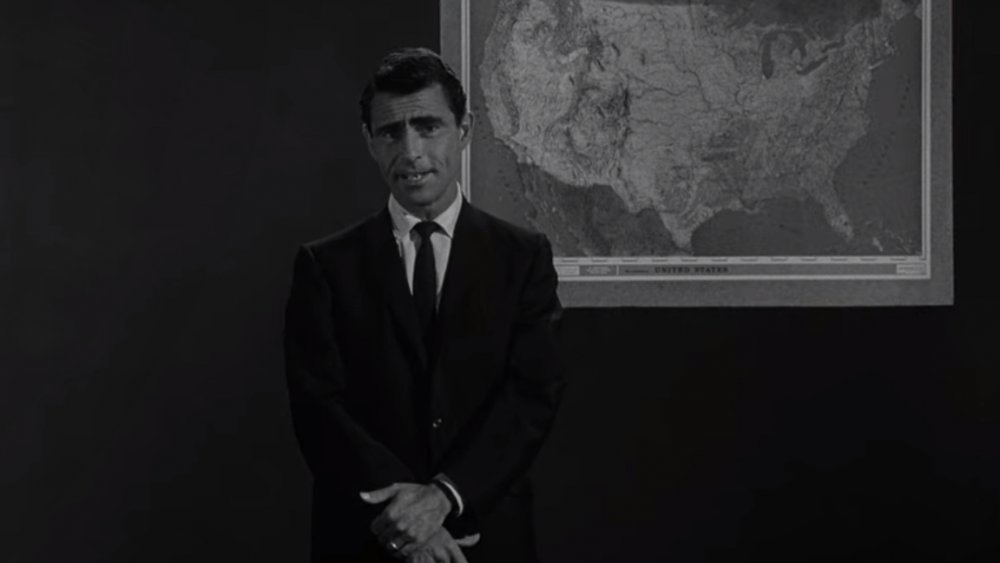

Beginning in 1959, Rod Serling invited viewers on a strange trip to another dimension, a wondrous land of imagination that was unlike anything ever seen on television before. Running for five seasons and 156 episodes (92 of which were written by Serling), the original Twilight Zone was a heady blend of science fiction, fantasy, and horror. In Serling's hands, those much-maligned genres, previously treated as kiddie fare in the relatively new medium of television, became serious vehicles for allegory and social commentary. Tackling serious themes such as racism, intolerance, and injustice, The Twilight Zone was sci-fi entertainment for adults.

Now in its fourth incarnation, The Twilight Zone is as relevant as ever. Nevertheless, after three reboots, a theatrical film, and a TV movie, all subsequent versions of The Twilight Zone lack the one vital element that made the original show a classic: Rod Serling, himself. This is his story.

Rod Serling's idyllic childhood

Rodman Edward Serling was born in Syracuse, New York, on December 25, 1924. The second son of grocer Sam Serling and homemaker Esther Cooper Serling, Rod was the family's unspoken favorite. A welcome surprise after his mother had been told by doctors she could no longer bear children, the Serlings doted on young Rod. A boisterous and outgoing child, he stood in contrast to his older brother, the quiet and withdrawn Robert Serling.

In 1926, the Serlings moved to Binghamton, New York. Known as "America's Parlor City," Binghamton, a mid-sized city in upstate New York, fueled Serling's imagination and his penchant for nostalgia. "Everybody has a hometown," Serling once wrote. "In the strangely brittle, terribly sensitive make-up of a human being, there is a need for a place to hang a hat, for, a kind of geographic womb to crawl back into. Binghamton's mine." Serling would return to Binghamton continually in his writing as evidenced by the Twilight Zone episodes "Walking Distance," about a harried ad executive who longs for simpler times, and the similarly themed but darker "A Stop at Willoughby."

Serling was the class clown

Young Rod Serling wasn't a particularly good student. Although he was a voracious reader, he had little interest in science and math and often required tutoring to make the grade. Outgoing, talkative, and witty, Serling quickly gained a reputation for being a "class clown." A gifted mimic, Serling's impressions always elicited belly laughs from his friends and family. Chief in his repertoire was a hilarious take on King Kong (a Serling staple into adulthood) and an uncanny imitation of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Frequently asked to sit in the back of the classroom, Rod Serling's mouth was a source of constant annoyance. Blind to his obvious potential, many of his instructors dismissed him as a lost cause.

However, at least one adult outside of his family recognized Serling's gifts. Seventh grade English teacher Helen Foley would inspire the future Twilight Zone scribe to hone his garrulous nature into a razor-sharp gift for oratory. Foley also encouraged Serling to channel his limitless energy into writing and drama. Soon, he was participating in public speaking activities, the debate team, and the student newspaper. With his teacher's unwavering faith, Rod Serling found both a purpose and a crucial component of his identity.

Serling was an athlete and a scholar

Naturally competitive and physically fit, Rod Serling loved sports. While attending Binghamton Central High School, he tried out for the position of quarterback for the school's varsity football team. Sadly, Serling's dreams of football stardom were smashed. At 16, the diminutive Serling was ten pounds too light to join the team. Serling would later joke that the coach "found it difficult to reconcile a quarterback who weighed less than the team mascot."

Undaunted, Serling joined the intramural football team and the tennis team where he was an aggressive competitor. High school classmate Sybil Goldenberg attributes Serling's determination to his size. "Because he was short he felt he had to prove himself doubly," she told Serling biographer Gordon F. Sander.

Serling remained self-conscious about his short height his entire life. Growing to five-foot-four-and-a-half-inches, Serling wore lifts and balked at being filmed in full frame for his Twilight Zone intro segments.

However, teenage Rod Serling was becoming a giant when it came to words. A valuable member of his high school debate team, his quick mind and humorous rebuttals were unmatched. Active in school politics, he successfully ran for General Organization president. By his senior year, he rose to the position of editor of his school's student newspaper where his fiery editorials would foreshadow his future as a defender of social justice.

Rod Serling goes to war

The United States had been embroiled in World War II for just over a year when eighteen-year-old Rod Serling enlisted in the Army on January 16, 1943. Having graduated from Binghamton Central High School just one day before, the patriotic young man might have dropped out and entered the fray earlier if not for the intervention of civics teacher Gus Youngstrom. "War is a temporal thing. It ends. An education doesn't," Youngstrom explained. "Without your degree, where will you be after the war?"

Initially, Rod Serling longed to be a tailgunner. Eager to get in the thick of the fight, he had read of the high mortality among tailgunners and naively decided that was where the action was. Uncle Sam, however, had a different plan for Rod Serling whose eyesight wasn't quite keen enough. Instead, he wound up in the 511th Parachute Infantry of the 11th Airborne Division.

Although Rod Serling had hoped to take on Hitler's forces in Europe, he was shipped off to the Pacific Theater. War was far from the adventure he assumed it to be. Stationed in the Philippines during the latter days of the conflict, Serling came face-to-face with the realities of combat. Seeing action at the Battle of Tagaytay Ridge and the siege of Manila, Serling was wounded numerous times and watched a friend die. For his service, Rod Serling was awarded the Purple Heart and the Bronze Star. Although the physical scars would fade, the psychological wounds never healed. The war haunted Serling and influenced him for the rest of his life.

Serling's college days

Following his service in WWII, Rod Serling took advantage of the G.I. Bill, a government program that provides educational assistance to service members and veterans, and enrolled at his brother Robert's alma mater, Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio. In Serling's own words, the war had left him "mixed-up and restless," and Antioch's work-study program perfectly fit his temperament.

Serling initially majored in physical education. However, a required first-year language and literature course taught by writer Nolan Miller soon rekindled his artistic passions. Switching majors to English literature and drama, Serling began to seriously pursue writing.

In 1946, he landed a job interning at New York City public radio station WNYC as part of his Antioch work-study. There, Serling got his first experience as a scriptwriter. The job delighted Serling who, in this small way, was following in the footsteps of his radio drama heroes Arch Oboler and Norman Corwin. He may have only been writing public service announcements and squibs, but it was still writing for radio.

Internships were rewarding, but they barely covered his expenses. Looking for fast cash, Serling decided to put his paratrooper training to use and took a job testing parachutes for the Army, per the AG Journal. At $50 a jump, this dangerous part-time job was an exciting way to pay the bills. One particularly dangerous test offered a windfall of $500, half to be paid before the jump and half after if he survived.

Rod Serling on the air

Once Rod Serling found his direction, he was single-minded in his determination to make a name for himself as a writer. By his junior year at Antioch, he was managing the campus radio station. Tasked with programming, Serling was free to create his own dramatic anthology shows in the vein of his radio heroes.

During this time, Serling also devoted himself to freelance writing and submitting scripts to popular radio shows. Initially, he had little success. However, his fortunes changed when his script for The Dr. Christian Show titled "To Live a Dream" took second prize in its weekly writing competition.

Intuiting that radio was in decline, Serling switched media and decided to focus on television. After a frustrating stint in local radio and TV, he devoted himself to freelance scriptwriting full time in 1952. Within a year, he was earning a living writing for such shows as Hallmark Hall of Fame and Kraft Television Theatre.

In 1955, "Patterns," a script Serling wrote for Kraft Television Theatre, would launch the young writer into prominence as a creative force in the new medium. A tale of corporate intrigue and cruelty, "Patterns" was a hit with both critics and viewers. Serling's next runaway success was "Requiem for a Heavyweight," a boxing drama written for Playhouse 90 which won the first Peabody Award for a teleplay. In under a decade, Serling had risen from struggling radio writer to acknowledged TV visionary.

Rod Serling versus the censors

Rod Serling's status as a writing powerhouse didn't guarantee him the creative control he craved. Censorship constantly frustrated his efforts to bring serious subjects to the small screen. Above all, Serling believed that TV was a medium through which controversial topics could be addressed head-on with maturity and sensitivity. However, skittish networks and sponsors feared they would lose revenue if TV drama became too controversial.

Serling learned a hard lesson about censorship with his 1956 script "Noon on Doomsday." Inspired by the tragic case of Emmett Till, a Black teen abducted, beaten, and murdered in Mississippi, Serling's script avoided overt racial connotations and instead focused on the moral dilemma faced by a defense attorney and the complicity of a small community in the murder of a Jewish pawnbroker, per NPR. Nevertheless, the tenuous connection to the Till case provoked the threat of a boycott in the South.

As recounted in an article archived by the Rod Serling Memorial Foundation, Serling's script suffered a death by committee. "The script was gone over with a fine-toothed comb by thirty different people, and I attended at least two meetings a day for over a week, taking down notes as to what had to be changed," Serling explained. "My victim could no longer be anyone as specific as an old Jew. He was to be called an unnamed foreigner ... Further, it was suggested that the killer ... was not a psychopathic malcontent, just a good, decent, American boy momentarily gone wrong."

Entering The Twilight Zone

Serling's struggle to bring "Noon on Doomsday" to the screen was one of a number of factors that led to the creation of The Twilight Zone. Tired of battling censors, Serling designed The Twilight Zone as a vehicle for adult drama rooted in imagination, fantasy, and science fiction. In a 1959 interview with Mike Wallace, Serling explained his motivation in creating the series. "I don't want to have to battle sponsors and agencies. I don't want to have to push for something that I want and have to settle for second best," Serling said. "I don't want to have to compromise all the time which in essence is what the television writer does if he wants to put on controversial themes."

The Twilight Zone originated with a rejected script titled "The Time Element." The teleplay written by Serling as his original pitch for The Twilight Zone tells the story of a man whose dreams allow him to travel back to 1941 to warn of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Judged "too far out," CBS shelved the script. Later produced as a 1958 episode of Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse, "The Time Element" was another hit for Serling. Garnering critical accolades and over 6,000 letters of praise from delighted viewers, "The Time Element" forced network executives back to the table with the visionary TV writer. Premiering on October 2, 1959, The Twilight Zone would be hailed as one of the greatest TV shows of all time.

Rod Serling's sci-fi success story

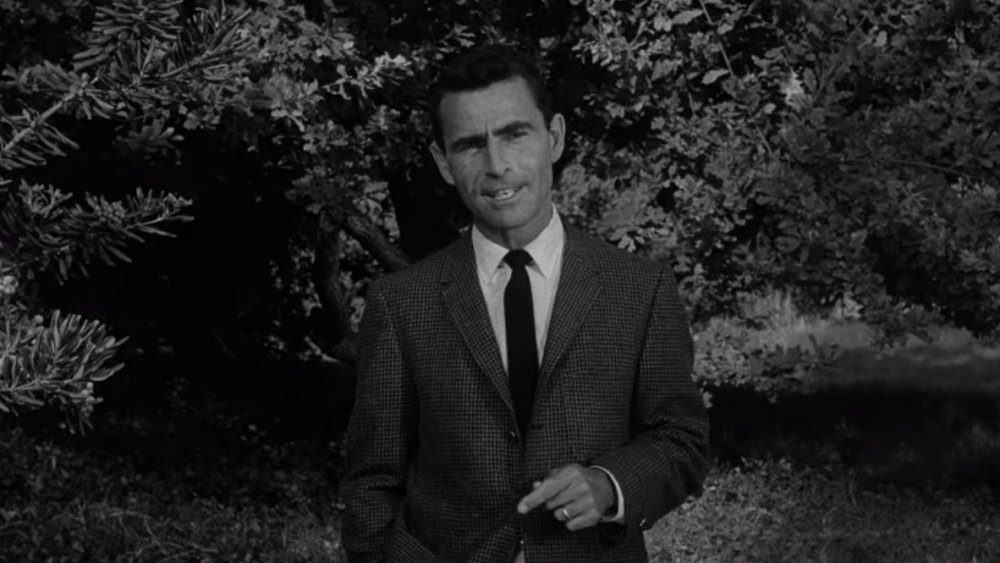

By declaring he was through with controversy, Rod Serling did a brilliant end run around the censors. With his social consciousness shrouded in allegory and the fantastic, Serling, at last, had free rein over The Twilight Zone.

With stories ranging from the poignant to the terrifying, The Twilight Zone is a landmark of television history. Over the course of its five-year run, the show won the Emmy for Outstanding Writing Achievement in Drama twice, won three Hugo Awards for Best Dramatic Presentation, and garnered creator Rod Serling a 1963 Golden Globe for Best TV Producer/Director.

In producing the show, Rod Serling enlisted the talents of the greatest science fiction and fantasy writers of the era. Among the authors to contribute scripts or stories to The Twilight Zone are such celebrated fantasists as Ray Bradbury, Richard Matheson, Charles Beaumont, Jerome Bixby, and George Clayton Johnson. However, the bulk of the show — an incredible 92 out of 156 episodes — was penned by Serling himself.

Along with its top-flight writing, The Twilight Zone featured stellar performances from such veteran actors as Burgess Meredith and Keenan Wynn as well as early appearances from future stars like Robert Redford and William Shatner.

Life beyond the Twilight Zone

Airing in the spring and summer of 1963, The Twilight Zone's fourth season marked a change in the program's format. However, expanding from 30 minutes to an hour proved a fatal blow to the once-lauded anthology. Compared with the fast-moving 30-minute shows, the hour-long format seemed ponderous. The Twilight Zone reverted to its original 30-minute runtime for its fourth season, but the die was cast. The Twilight Zone's final episode, "The Bewitchin' Pool" by Earl Hamner Jr., aired on June 19, 1964.

For a time, Rod Serling turned his attention to writing for film. His adaptation of the tense cold war novel Seven Days In May directed by John Frankenheimer received excellent notices, but otherwise, the TV writer had little success adapting to the strange medium. In the late 1960s, he adapted Pierre Boulle's novel Planet of the Apes for the screen. Serling's vision for the film proved far too elaborate for the budget. Despite numerous rewrites, the film's famous twist ending is undeniably Serling's.

In 1970, Rod Serling returned to television as host of NBC's Night Gallery. Initially enthusiastic about the horror anthology, his excitement waned as the show's format lapsed into formula. Without the creative control he had with The Twilight Zone, Serling found himself increasingly frustrated.

Serling goes back to school

Rod Serling's most personally rewarding post-Twilight Zone career was that of an educator. Serling first developed a love of teaching in 1962. While on a five-month sabbatical between The Twilight Zone's third and fourth seasons, Serling, fatigued from the strain of the show's rigorous schedule, accepted a position as writer-in-residence and part-time instructor at his alma mater, Antioch College. During his brief tenure, he taught classes in writing and drama as well as a course for adults on the social and historical implications of the media.

In 1967, Rod Serling took on a more permanent role as a guest professor at Ithaca College in upstate New York. Close to his home in Interlaken and far from the grind of television, Ithaca College was a place where the increasingly stressed writer could relax.

Teaching a course simply titled "Creativity," Professor Serling was anything but a typical college instructor. Former students recall his teaching style as loose, laidback, and filled with humor. Classes consisted of everything from nighttime film screenings to car rides through the Ithaca countryside. Above all, Serling's classroom was a place of open discussion where no topic was off-limits. Instilling a spirit of fearlessness and innovation in his students, the former Twilight Zone scribe advised his students: "If it's never been done before, do it. If it's never been shot before, by all means, shoot it."

Twilight of a TV pioneer

On May 3, 1975, Rod Serling suffered a heart attack while working in his garden. After a short stay in the hospital, he seemed to recover and remained in good spirits. Just two weeks later, another heart attack struck. Still, his sense of humor remained strong. "You can't kill this tough Jew," Serling joked from his hospital bed, per Serling.

Rod Serling's doctors determined that he would require a risky open-heart procedure to save his life. Years of overwork, stress and a three to five pack a day cigarette habit were taking their toll. While undergoing 10 hours of surgery to bypass blockages in his deteriorating arteries, he suffered a third heart attack on the operating table. Although the surgical team fought valiantly to save his life, he died two days later on June 28, 1975. Leaving behind his wife Carol and daughters Jodi and Anne, Rod Serling was just 50 years old.

Rod Serling's impact on television and continuing influence and relevance within the culture are immeasurable. However, to the generations of young people he continues to inspire, his true legacy is infinitely more personal. As daughter Anne Serling, author of As I Knew Him: My Dad, Rod Serling, told USA Today in a 2013 interview, "I hear from people in their 20s and early 30s who, because of my dad, became writers. That would have also deeply touched him."