What David Bowie's Most Famous Looks Actually Mean

The starman left Earth on January 10, 2016, just two days after his 69th birthday and the release of his final studio album, Blackstar. Already attracting respectable reviews from critics, upon the announcement of David Bowie's death, the album took on much greater significance. Fans and journalists alike reappraised the songs in light of his death, realizing that Blackstar was loaded with hidden meaning.

Tellingly, Blackstar was also the first on Bowie's 25 studio albums not to feature some version of the man himself on the cover — which has been interpreted as signaling that, by the time many fans were listening to the album, its creator would be gone.

The fact that such a gesture works is evidence of how important David Bowie's own image has been during a career spanning six decades. No other artist of his stature has given so much significance to his outfits, using them to give added resonance to the music itself. From album covers to live performances and music videos, Bowie's iconic looks have become inseparable from the music he was creating in each phase of his long career. Looking back over them gives a fresh insight into one of the 20th century's most transformative and unpredictable entertainers.

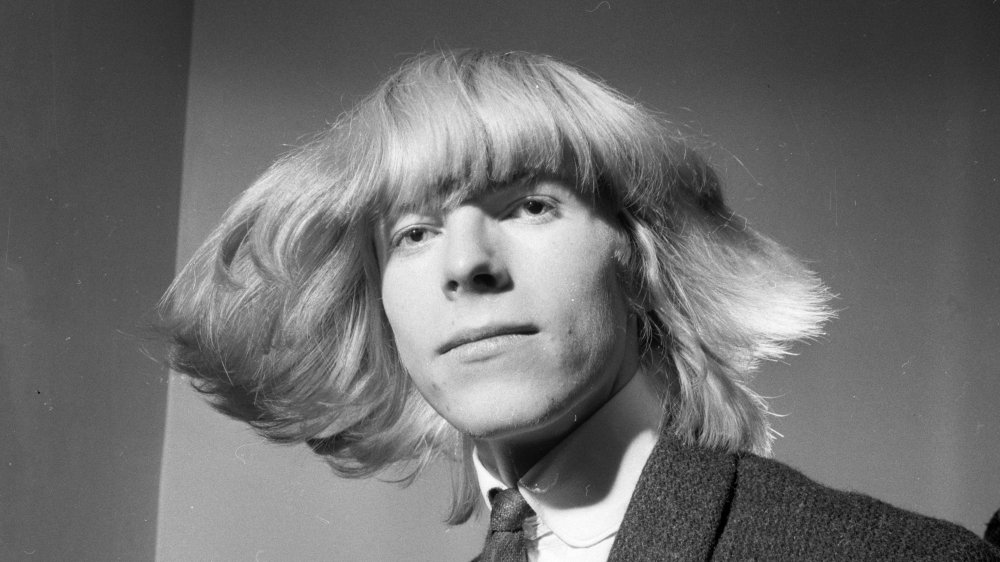

The long-haired young man

The 1960s were a turbulent time, and the decade was a tricky one for the young David Bowie, who at the time was still using a version of his birth name for performances. David "Davy" Jones performed in a great number of different groups during the '60s while still a teenager, with names such as The Mannish Boys and Davy Jones & The Lower Third. The young Bowie was experimenting with many different styles in the years prior to 1969's smash-hit "Space Oddity," and even recorded the misjudged novelty single "The Laughing Gnome," which is now thought of as a slightly embarrassing footnote in his otherwise stellar back catalog.

Bowie was, quite honestly, desperate for fame. Luckily, he and his manager, Less Conn, were already developing an eye for a good PR stunt, according to The Vintage News. In 1964, a 17-year-old David Bowie appeared on BBC television to promote a very tongue-in-cheek activism group, "The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Long-Haired Men."

Despite the impact of the Beatles and other groups at the time, the sight of a man with shoulder-length hair was still an oddity in the mid-sixties and could draw an aggressive response from people passing in the street, as the fresh-faced Bowie explains in the grainy black-and-white clip. As jokey as it is, it is an early insight into Bowie's interest in audience responses to how he looks, and what his style might mean to them.

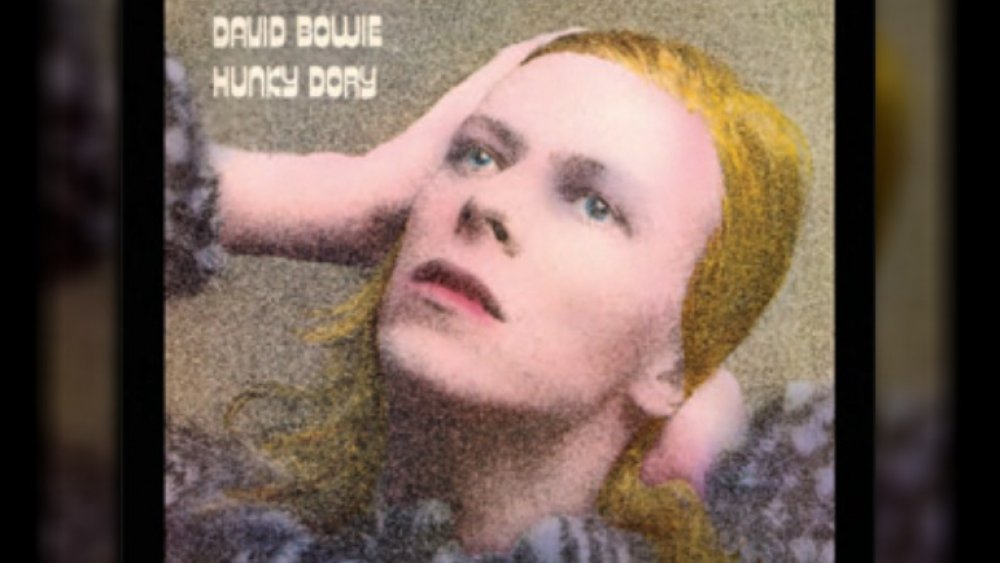

David Bowie's early androgyny

Though Space Oddity was a huge hit for Bowie, the proximity of its release to the Apollo 11 moon landings meant that David Bowie was labeled a novelty act in the early 1970s, per Yahoo. Bowie, however, continued to plow his own furrow, and expand both his musical and sartorial styles in imitation of some of his greatest influences, which he wore proudly throughout his career.

But whereas his early releases saw David Bowie referencing such musical influences such as The Yardbirds and Jacques Brel, before long Bowie began to gesture towards the other arts that he was equally interested in. For the cover of 1971's Hunky Dory — which is now considered by many to be the first classic Bowie album — Bowie reportedly took inspiration from one of his Hollywood heroes, Marlene Dietrich. According to NME, the shot, taken by Bowie's schoolfriend George Underwood, is an attempt to recreate an image of the actress which Bowie had brought to the photoshoot.

Bowie was experimenting with androgyny in the early '70s, and he and his wife referred to him by the nickname "The Dame". The move was an answer to the hyper-masculinity that dominated both the folk scene, which David Bowie was first a part of, and the glam rock that filled the British charts. Vanity Fair claims Bowie is referred to as "the actor" on the album sleeve, a gesture towards the characters that would populate Bowie's work for the rest of his life.

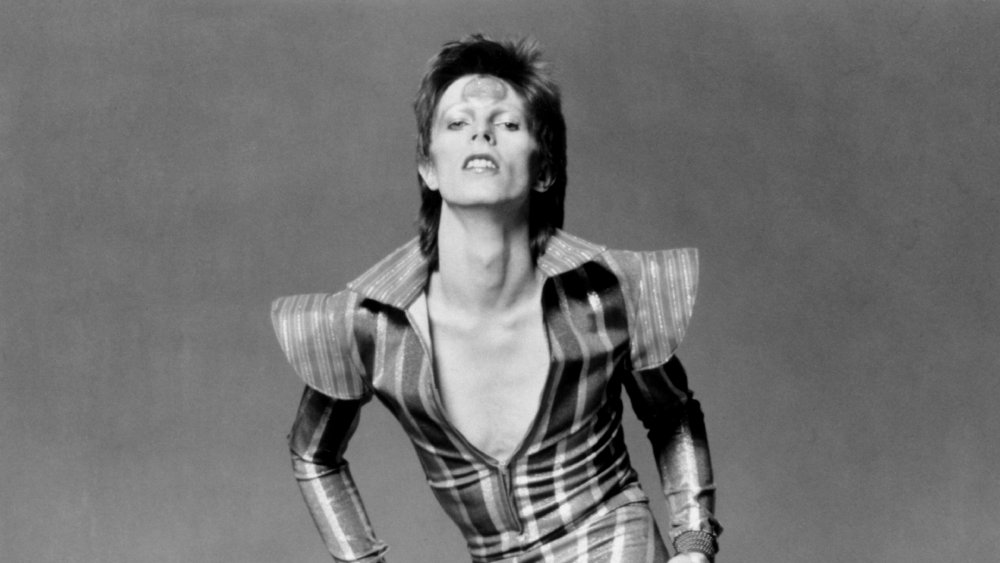

The landing of Ziggy Stardust

Bowie's mainstream breakthrough occurred in 1972, with the arrival of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars LP. But Ziggy... wasn't simply an album: it was a whole concept and world, complete with its own story, characters, and, of course, outrageous outfits.

Ziggy Stardust, an "omnisexual alien rockstar" according to Rolling Stone, is sent to Earth to warn humanity that it is in its final five years of existence, and to deliver a message of hope and love. Originally, Ziggy was envisaged by Bowie as the lead character in something akin to a West End Musical, who Bowie himself would portray for an initial run before handing the show and the character over to another performer.

But the look — an outrageous orange mullet paired with space-age, colorful outfits which were the work of Japanese designer Kansai Yamamoto — became instantly identifiable with Bowie. Though Ziggy was a character in his own right, he became David Bowie's alter-ego throughout the mid-seventies, through which Bowie could critique the glam rock and pop scene in which he suddenly found himself a major player.

In the Ziggy story, the alien is finally torn to pieces onstage by his frenzied fans. In actuality, Bowie himself would kill off the character, announcing at the Hammersmith Odeon on July 3, 1973 that he would never perform on stage as his most famous character again.

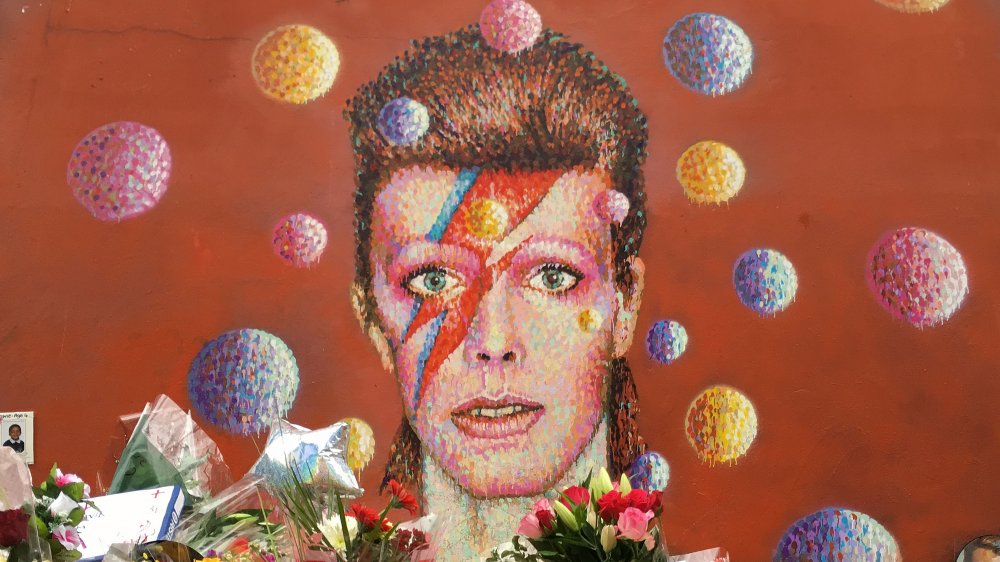

Aladdin Sane's split personality

David Bowie fans have plenty to argue about when it comes to which is the best of the 25 studio albums he released during his career. But few could disagree that the cover for 1973's Aladdin Sane is his signature image. The lightning bolt, especially, is closely liked to Brand Bowie and adorns official and bootleg merch, fan art, and tattoos. It was also the image of Bowie that recurred most often in memorials of the singer around the world.

The idea of lightning facepaint was David Bowie's own, who told Rolling Stone that the make-up, by the artist who had painted him as Ziggy, Pierre LaRoche, signified that his new persona was "cracked" by the bolt. Many critics now believe that the design symbolizes Bowie's mixed feeling about his recent superstardom, and has described the album that the design adorns as "Ziggy does America," with Bowie already envisaging himself as washed up, having given in to the excesses of his new lifestyle. The album was written on a world tour, and the strain was already beginning to show, as can be felt on the track "Cracked Actor," which the lightning bolt design seems to reference.

Bowie made the best of things with Halloween Jack

David Bowie's early career was riddled with failures, but many dead ends he went down learning his trade in the 1960s taught him an important lesson: to roll with the punches. After Aladdin Sane, Bowie had some very ambitious artistic visions, but, as in the '60s, nothing was to work out quite as he intended.

In 1973, Bowie began planing a musical version of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, which was one of Bowie's favorite books. Bowie met with a potential director for the work, according to his biographer Nicholas Pegg, and claimed to have written 20 songs for the show.

However, Orwell's widow, Sonia, refused to grant Bowie the rights to her late husband's work, per the Guardian. Instead, Bowie went about creating his own world. Taking further inspiration from William Burroughs' 1971 novel The Wild Boys, Bowie created the decaying metropolis "Hunger City," which became the setting for the songs featuring on Bowie's next album, Diamond Dogs.

Bowie's new persona, Halloween Jack, is the leader of the albums titular gang. Bowie's look for Jack has a look similar to Ziggy, with the shock of red hair remaining as a continuation, but with a more coarse, picaresque ensemble to denote the character's earthliness and criminality. The most noticeable addition is an eyepatch.

Bowie's Thin White Duke

David Bowie moved to Los Angeles in 1975, where his hectic professional schedule led to him quickly developing a cocaine habit, according to Rolling Stone. In the years since, Bowie has described the period in which he created the album Station To Station — his "(first) masterpiece", according to music critic Lester Bangs — as the lowest point in his life. And the character he created to get himself through it is a reflection of the angst and addiction that dominated this phase of his life.

The Thin White Duke — whose name perhaps serves as a euphemism for cocaine itself — was a character portrayed by Bowie at his slightest, weighing, at one point, less than 100 pounds. Signified by a monochrome black and white attire that employed two pieces of a three-piece suit, according to Timeline, this persona is the one that almost consumed its creator. At the time, Bowie was indulging his obsessions, including occult mysticism and, unfortunately, fascism. The Thin White Duke was described by Bowie as an "Aryan Superman," and Bowie became entangled in fascistic beliefs that were difficult to attribute; were contemporaneous interviews reporting the words of Bowie, or the Duke? Bowie sought rehab and later described the Duke as a "nasty" character. "He was an ogre for me," Bowie stated.

Bowie in Berlin

There are a number of famous partnerships that illuminate the story of David Bowie, starting with Mick Ronson as a member of the Spiders From Mars, to John Lennon who co-wrote and performed on the Bowie single "Fame," to producers Brian Eno and Tony Visconti, who separately were instrumental in guiding the sound of David Bowie records at vital times throughout his career. But it was perhaps Iggy Pop, whose final album with The Stooges, Raw Power, had been mixed by Bowie, who performed an intervention on the drug-addled post-L.A. Bowie which may very well have saved his life.

The two musicians moved to Berlin, where they were later joined by Eno and Visconti and Bowie's wife, Angie. There, they filled up the vacuum of cold turkey with productivity. Bowie released what was to later be known as his "Berlin Trilogy," Low and Heroes, both released in 1977, and 1979's Lodger. He also produced two Iggy Pop albums during his three years in the German capital, according to Ultimate Classic Rock.

Photos of Bowie from his time in Berlin show him in uncharacteristically practical clothing, a surprisingly personal portrait of the real human being during a period of recovery. As described by Sleek, it is as though Bowie is finding "refuge in the relaxed style of Berlin."

Pierrot the Clown

Though he became one of the greatest rock stars of the century, it seems David Bowie could have succeeded in whatever creative pursuit he wanted. Bowie began as a saxophone player before becoming a singer, but also performed in a number of short films and theatre performances before he was a household name. At one time, he trained as a mime artist and was masterminding a performing arts group called "Feathers" before he gained success as a rock star. In fact, his old bandmate David Hadfield recalls having to convince the young Bowie to sing in the group, back when he was happy to just be a sax player, according to Ultimate Classic Guitar.

The outfit for Pierrot the Clown harks back to Bowie's early interest in theatre and performance art, but unlike Ziggy Stardust and the Thin White Duke, Pierrot can not be said to be Bowie's own creation. The character, who features on the cover of 1980's Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) and the legendary music video for the single Ashes To Ashes — which, at the time, was the most expensive music video ever made — is a callback to the first theatrical role that Bowie portrayed all the way back in 1968, in the play Pierrot in Turquoise. Bowie didn't, in fact, play the role of the clown, but the character also featured on the album art for the Space Oddity album, painted by his friend George Underwood.

Serious Moonlight, Serious Money

Although the run of albums from Station To Station to Scary Monsters had been successful both critically and commercially for Bowie, it is true that he was at risk of becoming a bit of a downer. His music over this period is full of existential angst and psychological strife, a comedown from his boom years when he went out onto the stage each night and introduced himself as Ziggy Stardust.

But everything changed for Bowie in 1983, when he teamed up with the mastermind behind Chic, Nile Rodgers, for what would become the most globally successful period of his career. With the release of worldwide smash Let's Dance in 1983 and the accompanying "Serious Moonlight" tour — and the end of some serious financial problems — Bowie was back in the limelight as a bona fide superstar. His outfits of the period reflect this, with classic suits that signal the return of Bowie "the entertainer" as opposed to the angsty artist of the Berlin trilogy.

According to David Bowie World, one critic described the period as his most accessible, as it "had few props and one costume change, from peach suit to blue."

Horrifying Button Eyes

The late '80s to the early 2000s were patchy for David Bowie, with a string of albums of varying styles that were generally met with mixed reviews. It is perhaps telling that there isn't one particularly iconic outfit, from this time, either.

In 2004, Bowie suffered a heart attack on tour, and retired from the public eye for almost a decade, before re-emerging in 2013 with the surprise single "Where Are We Now?" which referred back to his Berlin period, and the eclectic rock album The Next Day, which featured an altered version of the cover to Heroes as its artwork. Bowie was back and looking back.

Released almost two years later, Bowie's final project, Blackstar, became a fountain of potential meanings upon Bowie's death. The album contained many lyrics that seemed to foretell his passing or cryptically hint at the nature of his condition. But the music videos, too, seemed packed with hidden symbolism, and none more baffling than his new and disturbing character, "Button Eyes," who appears in both the videos for "Blackstar" and "Lazarus."

The videos' director, Johan Renck, has discussed how, though Bowie himself gave suggestions for the symbolism, their meaning must remain between he and Bowie, and that interpretation is up to the viewer, per Vice. However, Davidbowieautograph.com has suggested that the blindfold is a reference to Victorian death rituals.

Lazarus and the Kabbalah outfit

David Bowie's last album and his final two videos have been said by many critics to be laced with references to alternative religious practices and the occult. One of Bowie's long-standing interests was the Kabbalah, a form of Jewish mysticism that was an inspiration for Bowie's lyrics and cover art all the way back in the mid-1970s.

According to HuffPost, Bowie collaborated with photographer Steve Schapiro for a series of portraits that saw Bowie in a silver and blue striped bodysuit, surrounded by doodles of circles and connecting lines that represent the Kabbalah Tree of Life, the doctrine of which also influenced the lyrics to the title track of Station to Station.

The outfit reemerges for "Lazarus" as the last outfit of Bowie's career (wearing it, he retreats into a closet at the end of the video, and pulls the door closed), suggesting the significance of the Kabbalah in his final work, as the Times of Israel points out.

In the video, Bowie is again seen doodling — this time manically, with the symbols he creates spilling over the edge of the page. Critics have interpreted the symbols as chemical equations for nuclear reactions akin to those that occur on the sun — or possibly on the titular "Blackstar." The connection to the '70s shoot adds further meaning to these symbols, allowing us to reinterpret them as a nod towards the "creative energy" that sustained Bowie right until the very end.