Groundbreaking Women They Didn't Teach You About In School

As many schools teach it, history is a book filled with tales of men. And sure, there's definitely a lot of men who made massive contributions in fields from science, music, and medicine to archaeology, aviation, and alternate fuels, but there were women who made contributions just as important.

Unfortunately, we don't seem to hear about them nearly as much, and that's a shame. Some of their stories are nothing short of incredible: they're stories of exploration, uncharted frontiers, and sometimes, some seriously death-defying stuff. These women were simply brilliant, and channeled that brilliance into groundbreaking achievements we can still see and hear today.

So let's talk about just a few of the women who changed their world, shaped ours, and don't get the recognition they deserve. Until, that is, someone makes a movie about them, because honestly, we'd watch the heck out of a series about any one of these groundbreaking women.

Gerda Taro: Risking it all to document the front lines

Gerda Taro was born in Germany in 1910, and when she was 23-years-old, she was arrested for speaking out against the Nazis. According to AnOther, that's when the young Jewish woman headed to Paris and met another refugee — the Hungarian Endre Friedmann.

They met — and became lovers — on the cusp of another major conflict: the Spanish Civil War. In 1936, the photographers headed to the front lines where they continued to work together, even sharing cameras at first. For the next year, Taro returned to Spain again and again. During each trip, she headed to the front lines, and captured photos of the conflict... while being right in the middle of bombs, machine gun fire, and death.

According to the BBC, the only thing that got her off the front lines was when she needed more film, and that's where her life came to a tragic end. On July 25, 1937, she was celebrating a batch of new photos when she jumped onto the running board of a car. The car collided with a tank, and she was crushed. She died the next day, and Friedmann — now known as Robert Capa — spent the rest of his life regretting that he hadn't been there. While her photos were forgotten for a long time, they were recently rediscovered by the International Center of Photography, who still remembers her for her work and as the first female photojournalist to die in combat.

Sirimavo Bandaranaike: Mother, grieving widow, political powerhouse

When it comes to women in positions of power, Sri Lanka's Sirimavo Bandaranaike broke through that glass ceiling in 1960, when she became the world's first woman elected to the position of prime minister. According to The New York Times, it was a position that only came after heartbreak. In 1959, her husband — who was then prime minister himself — was assassinated. In the wake of his death, she was elevated to the head of the political party he had founded, and was then elected to take his place as prime minister.

Bandaranaike was born in 1916 to one of the country's wealthiest families, married into a family just as elite, and definitely made some highly controversial decisions, like changing the admissions policies of universities to favor one ethnic group over another. She also promoted keeping her country out of international relations and skewing toward socialist policies, and was popular enough that after being elected in 1960 and leaving office in 1965, she was elected to two more terms (via Britannica): 1970 to 1977, and 1994 to 2000. Her children followed her into politics, with her daughter holding office as both prime minister and president.

The historian KM De Silva had this to say about her legacy: "After her husband died, there was so much confusion and the party was almost collapsing. She was an untried leader. But she not only survived, she sustained the party and the family in politics."

Marion A. Frieswyk: The CIA's first female intelligence cartographer

During World War II, the CIA was still in its infancy: it was an organization called the Office of Strategic Services. According to The New York Times, about a third of their 13,000 members were women who worked in all kinds of fields. Julia Child developed shark repellent, for example, and others worked as spies, filmmakers, and even forgers.

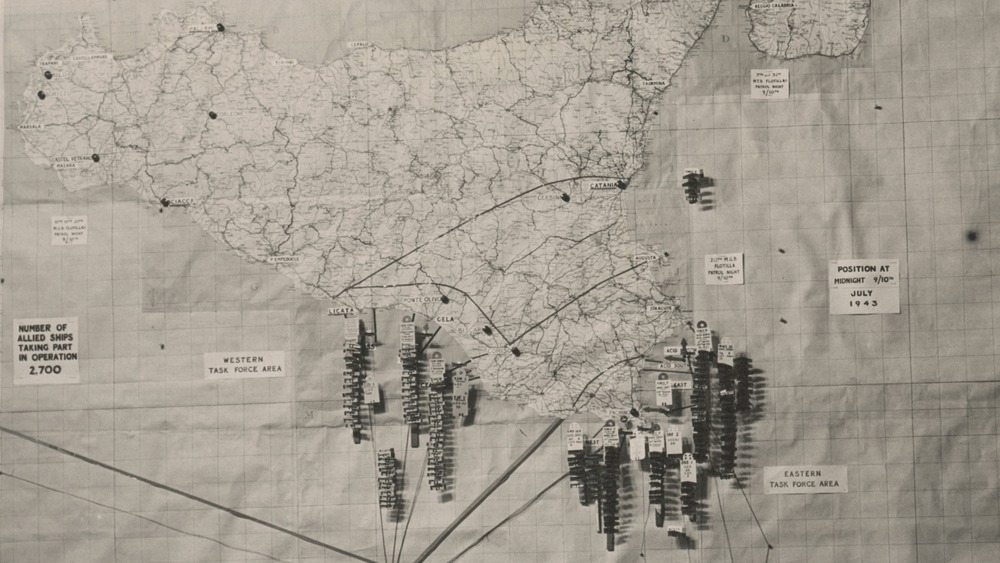

Then there were women like Marion A. Frieswyk, the organization's first female intelligence cartographer. At a time well before Google Earth, it was up to cartographers to draft maps based on information gathered by intelligence agents — and that's what Frieswyk did. The CIA credits her and her team with creating "a unique system of map production," that evolved into not just incredibly detailed and accurate maps.

Some of the maps she worked on included one for the Joint Chiefs of Staff: they were planning the invasion of Sicily, and it was her 3D topographic map that they used. It was a huge jump for the girl from upstate New York who had "a knack for numbers." Her plans to be a teacher went out the window with the outbreak of the war, and after just a six-week crash course in economic geography, she became instrumental in turning information into maps. Her map of Sicily was so invaluable that it wasn't long before more requests came rolling in, and she stayed with the CIA well after the end of the war.

Lhakpa Sherpa: The world record-holding mountain climber

While it's Edmund Hilary that gets most of the attention when it comes to scaling Mount Everest, it's a woman who holds some serious records. In 2019, The Guardian interviewed Lhakpa Sherpa in her Connecticut apartment, and they were amazed not only by her accomplishments, but by her complete lack of benefits: while many climbers might have sponsors, nutritionists, and endorsements, she had none of these. The mother-of-two was, at the time, working at Whole Foods as a dishwasher, and raising her two daughters on her own. She had met her husband on Everest, but when the relationship descended into a pattern of domestic abuse she left and took her girls with her.

Nineteen years prior, she had become the first Nepalese woman to climb Everest and survive the ascent and descent — and even more impressive, she'd done it another nine times after that. One of those times, she did it just eight months after giving birth to her first child, and another time, she was two months pregnant with her second.

Why does she do it? "Climbing is my way out of washing dishes. It is the way to make a better life for the girls. [...] I want to show the world I can do it. I want to show all the women who look like me that they can do it, too."

Jackie Ronne and Jennie Darlington: Antarctic explorers

According to National Geographic, Edith "Jackie" Ronne (pictured) didn't know she was going to Antarctica in 1947 — not until she was literally on her way. It was her husband, Commander Finn Ronne, who was leading the expedition. After an accident forced him to head back to Washington, D.C. and get a new plane for their mapping operations, he sent his wife ahead and tasked her with keeping things on schedule. She did — and by the time he re-joined them, he'd made her the 23rd member of the expedition, and had drafted legal documents that stated if anything happened to him, she was the new expedition leader.

And that's how Ronne became not only the first American woman on Antarctica (and the first to spend the winter there), but also the first female working member of an expedition to Antarctica, overseeing the scientific research conducted during their time there, and handling the team's PR.

And she wasn't the only woman on the trip. Harry Darlington III, the expedition's senior pilot, brought his wife Jennie along, too. According to The Washington Post, she only decided to go at the last minute, too: other expedition members later said it was a good thing she did, because even though she didn't have a specific role, she turned out to be invaluable at smoothing over the inevitable tensions that come from close quarters, accidents, and arguments.

Jeanne Barret: First around the world

According to the New York Botanical Garden, Jeanne Baret's journey started in 1766. Then 26-years-old, she was already studying with a well-known naturalist named Philibert Commerson. When Commerson was hired on as the botanist for an expedition to explore some of the farthest reaches of the world's then-unknown territories, he wanted Baret as his assistant.

The problem was that the ship they were sailing on was French, and French law prohibited women from joining a crew. So, they dressed her as a man, called her Jean, and she ended up not just going, but serving as chief botanist for much of the journey as Commerson was largely incapacitated by illness. She's now credited with collecting more than 6,000 species of plants, but it's not all a happy story.

Sources agree that eventually it was discovered she was a woman, and NPR says there's two different versions of what happened. Bougainville, the captain of the expedition, says that they were in Tahiti when native people figured it out and her crewmates saved her from a terrible fate, but journals written by other crew members say that her secret was discovered in Papua New Guinea, and that she was immediately assaulted by her crew. She and Commerson were kicked from the expedition in Mauritius, where he died. She married a French soldier and returned to France, completing her journey around the world.

Christine de Pisan: The first woman to make her way by her pen

It's common knowledge that throughout history, women often weren't given the same educational opportunities as men. Christine de Pisan was an entirely different story. It started with good fortune: her father was Tommaso da Pizzano, royal astronomer to France's King Charles V. When Christine was born in 1364, he gave her the same education that he gave his sons. She loved it — National Geographic says that she was the sort of person that was writing poetry as a child.

She married when she was 15, and it seems to have been a happy one that gave her three children. But when both her father and husband died around 1389, she refused to go the traditional route and remarry. Instead, she supported herself, her three children, and her mother by becoming the manager of a scriptorium, and best of all, she kept writing poetry and sending them to influential figures in hopes of getting a patron.

It worked. She became a full-time writer with patrons like King Charles VI, Queen Isabella of Bavaria, and Phillip II of Burgundy. In addition to poems, she wrote some of the world's first feminist literature, and became an outspoken critic of what was essentially a medieval trope: the idea that female characters exist only as an object of desire. She died in 1430, not long after writing the only piece of literature about Joan of Arc that was composed during her lifetime.

Carol Kaye: Music history's most prolific bassist

If you've heard anything from the Beach Boys or the theme song from Batman, you've heard the work of Carol Kaye. In fact, if you've heard pretty much any song from the 1960s, you've heard her: as the only female member of a group of studio musicians called The Wrecking Crew, Kaye has played bass on somewhere around 10,000 songs over the course of her career.

She didn't just play, either — she wrote. According to UDiscoverMusic, there's some iconic sounds that were all her: she created the bass structure for the famous "Theme from Shaft," and the beat of Sonny and Cher's "The Beat Goes On," was her, too.

Kaye was a natural: she told Music Man that she had been working as a professional musician and teacher since she was 13 and by then, she'd already been holding down a job for four years. She started out on guitar but gravitated toward bass because of its versatility, and her break came in 1963. She was asked to step in on a recording session for Capitol Records, and from then on, well, frequent collaborator Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys said this of her: "Carol Kaye was the greatest bass player I've ever met."

Mary Heath: The woman who kicked open the door of aviation

Lady Mary Heath's life reads like a movie, starting when she was just a year old: her father bludgeoned her mother to death and was found both guilty and insane. Raised by her aunts, she was encouraged to get an education — and once she did, she headed off to World War I, where she worked as a dispatch and ambulance driver (via Limerick Life). She got interested in aviation, was flying solo within a few weeks of taking her first lesson, and found herself confronted with a massively chauvinistic attitude throughout the entire industry. She was not about to stand for that.

Even as she went on to break some serious records — and, notes RTE, become the first woman to fly solo from South Africa to London — she made a point to wear fur coats and pearls while she did it. She even opened a pretty big door: at the time, aviation regulations banned women from holding jobs as commercial airline pilots, because menstruation was classified as a "disability." She changed that — by completing a series of tests before an all-male board who had requested she do it all while in mid-menstruation. Needless to say, she passed.

Sadly, her story doesn't have a happy ending. A severe accident in 1929 left her with a fractured skull and nearly blind, and when she remarried a Jamaican jockey, racism spelled the end of her career and her achievements were eclipsed by Amelia Earhart.

Amelia Edwards: Shaped archaeology and travel writing as we know it today

Born in 1831, Amelia Edwards started out first as a travel writer. She'd been writing since she was a child — she submitted her first poem to a literary journal when she was seven — and she didn't just travel, she traveled. According to the Egypt Exploration Society, she wrote her fiction from first-hand experience she usually got by disguising herself as a man and heading into places that were off-limits to women, like the gambling dens, bathhouses, and brothels of Paris. She did a ton of travel-writing, too, and it was when she went to Egypt that her life truly changed.

She ended up there accidentally, blown off-course by bad weather while she was in Italy. So, she did what no other woman had: she traveled the length of the Nile, wrote an in-depth account of it, and illustrated it with her own watercolors.

Edwards was enamored with this new land, and according to English Heritage, she went on to become a champion for the preservation of Ancient Egyptian artifacts, as well as research into the ancient culture. She founded the afore-mentioned Egypt Exploration Society, and when she died in 1892, she gave her entire collection of Egyptian artifacts to University College London, founding their Egyptology department and endowing their chair in Egyptology.

Thank them for the weather app on your phone

Sure, the weather forecast is right at our fingertips today, but back in 1950, the only computer with any chance of figuring out forecasts was a 150-foot long monstrosity called ENIAC. The Smithsonian says it was insanely complicated: in order to get ENIAC to make predictions about the future, they had to teach it about the past — and that's where Margaret Smagorinsky comes in. She was the Weather Bureau's first female statistician, and she manually did all the complicated equations they needed to teach ENIAC.

There were other women working on the project, too, but one of the most important was Klara von Neumann (pictured), a wealthy Hungarian figure skating champion with a knack for numbers. She was married to John von Neumann (who was working on the Manhattan Project, and was the inspiration for Dr. Strangelove), who wanted to do something good for the world after seeing the outcome of his work on the hydrogen bombs. That was ENIAC, and weather forecasting.

He brought his wife on board, and what followed was a mind-numbing amount of math that she described as a "very amusing and rather intricate jigsaw puzzle." Under their guidance, ENIAC became one of the first computers that had programs stored in its memory, and produced the very first computer-generated weather forecasts. It took five weeks, and during that time she was the one who hand-punched and organized the 100,000 punch-cards that made up ENIAC's memory banks.

Pioneers in solar technology

Concerns about clean energy are nothing new — according to the Smithsonian, researchers have been exploring alternatives to fossil fuels since at least the 1940s. That includes Maria Telkes, an engineer and biophysicist who emigrated to the US from Hungary in 1925. She became interested in the idea of harnessing solar energy, and in 1940 she joined MIT's Solar Energy Conversation Project. That led her to something super cool: the Dover House project, which had an end goal of building a house that was completely powered by solar energy.

And it absolutely worked. Three women came together to build it: Telkes was behind the technology, the house itself was designed by the architect Eleanor Raymond, and the whole thing was funded by a conservationist and sculptor named Amelia Peabody. Instead of using solar panels, Telkes' technology harnessed a chemical reaction and essentially used the crystallization of sodium sulfate to collect, store, and release heat.

One of her cousins (and his family) lived in the house for two years, proving it was viable until the chemical reaction was eventually exhausted. Telkes moved on within the field, developing solar stoves, heaters, and solar materials later used in the space program.