Why The Town Barber Was The Most Powerful Person In The Wild West

Fans of the Andy Griffith Show can't help but remember Floyd the Barber, the seasoned stylist whose shop was often filled with Mayberry locals discussing various matters at hand. Indeed, Floyd's was the epitome of barbers across America who serve, even today, as a central point in finding news and advice about their communities. According to Avenue Five, the profession dates all the way back to Egyptian times, circa 3500 B.C. Early barbers, confirms Western Fictioneers, were looked upon as some of the earliest surgeons and dispensers of medicine for various illnesses.

Remnants of barber history in the medical field remain today in the form of the barber pole, whose red, white and blue colors actually have nothing to do with the American flag, says History. But although the services barbers offer has changed over time, the essential goal of visiting one remains the same: get a shave, get a haircut, and engage in local gossip about sports, politics, the community, and other important news of the world. The same was true in the Wild West, when barbers remained an important hub for news, trusted advice, and of course, cleanliness. Read on to find out why barbers were some of the most important, and powerful, people in the west.

Early barbers were men of medicine

The National Barber Museum confirms that barbers of the Middle Ages, in addition to cutting and shaving hair, were often called upon to dress wounds and perform surgery. Called barber-surgeons, these knowledgeable men knew how to treat wounds and practiced other essential medical expertise. The Barber Surgeons Guild identifies the duties of these men as including bloodletting, dental extractions, surgery, and even amputations. By the 14th century, England's barber-surgeons fell into one category of the profession, with those practicing only salon techniques in a second category. Why weren't these important procedures left to physicians? Because doctors were not taught such things "due to their limited knowledge on its invasive nature." And notably, becoming a doctor would not even require a medical degree for several more decades.

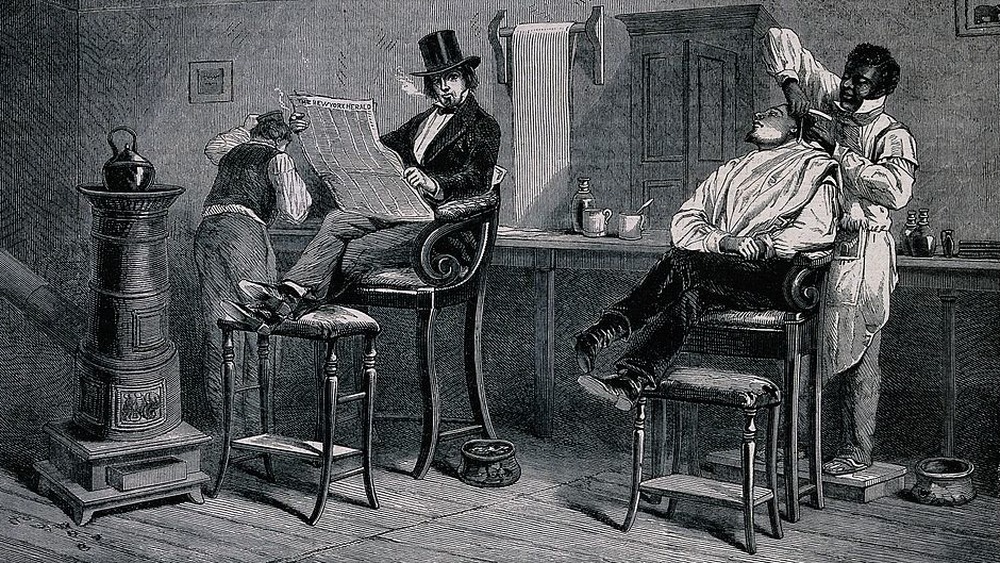

By the time of colonial settlement in America, barbers were not practicing medicine on their customers as much. But barbering also was considered menial work and therefore relegated to black slaves by their owners and performed at home. According to Philadelphia Encyclopedia, commercial barbers made do by making and maintaining the powdered wigs worn by the wealthy and making house calls to fashion fancy hairdos for the ladies of the house. In time, however, German immigrants who had practiced barbering in their homeland began offering more common services to the working man on the street.

The evolution of barbering in America

By the late 1840's, the prelude to the Wild West era of the 1860's, most barbers in America had given up their medical instruments in favor of just pursuing hygiene — that is, making sure their customers received a clean shave, a washed and cut head of hair, and sometimes offering baths. Vintage Everyday says men sported "fairly short" hair styles, which likely required frequent trips to the barber. Thus barbers were in high demand. As early as 1852, the Nevada Journal reported on T.C. Green, who left Nevada City owing money to his barber and others. Yet barbers also, according to Western Fictioneers, might be called upon to "remove a bullet, pull a tooth," or even amputate a limb if there was no doctor available in his primitive frontier town.

Indeed, many early American "tonsorial" parlors offered myriad services with regards to health and hygiene. When barber Henry Edwards announced he was opening a full service bath house in Mokelumne Hill, Calif., in 1852, the Calaveras Chronicle not only applauded him as "one of the most expert and light handed professors of the tonsorial art" but also stated that nothing was more "conducive to comfort and health than personal cleanliness." And everyone in town soon found solace at the barbershop, where men could discuss the news of the day and air their thoughts.

What did it take to become a barber

It's easy to believe that becoming a barber was relatively easy in the Wild West. Not so much. For one thing, how easy was it to trust a man holding a straight-edge razor to your neck? Or one who was about to yank that painfully rotten tooth? By 1876, says American Barber, official standards and regulations for barbershops began taking hold in America. We can credit Georgia barber Alonzo Herndon for creating the Atlanta Barbers Advancement Association as a way to lead professional barbers to success. Similar organizations and unions were formed in 1887 in Ohio and New York. But there were no such organizations out West.

At the very least, barbers in the Wild West could get some instruction from A.B. Moler's textbook, The Moler Manual of Barbering, beginning in 1893, according to Golden Gate Exclusive. The handy manual was followed by Frank C. Bridgeford's 1900 book, the Barber instructor and toilet manual. But not until 1897 were laws passed requiring barbers to be licensed. And even the first of these were issued in far-off Minnesota. Nobody seems to be able to lay a finger on how barbers of the Wild West trained for the trade. Western Fictioneers simply notes that in those primitive times, barbers set up shop in back of saloons or, if he was lucky, in his own one-room office or even a tent.

Barbers as the Wild West knew them

By the 1860's, the beginning of the Wild West era, men had expanded their facial hair to include beards, chin whiskers, or mutton chops, as well as sideburns and even mustaches, according to Indiana's Tribune Star. And thanks to Uncle Sam during the Civil War, goatees became quite fashionable as well. Such a lot of hair certainly needed grooming on a regular basis, especially for men whose work included toiling in the mines, prospecting for gold, or working as cowboys. Arizona historian Marshall Trimble says that when men rode into places like Dodge City after two months out on the range, the first thing they did was head to a barbershop for a bath and a shave.

Trimble's statement is backed up by documentation of the day. When loggers Charles Lyons and Ben Robbs received their pay in Oregon, Robbs would later verify they went to Klamath Falls where they checked in to a hotel before heading to the Road House for a few drinks and to get their faces shaved. Lyons' and Robbs' visit to the barber occurred in 1911, at which time, according to Vintage Everyday, facial hair might have fallen out of fashion. Still, keeping up the rampant change in styles over time was important, and Frank Bridgeford's Barber instructor and toilet manual duly confirmed that "the occupation of barber is an institution of civilized life."

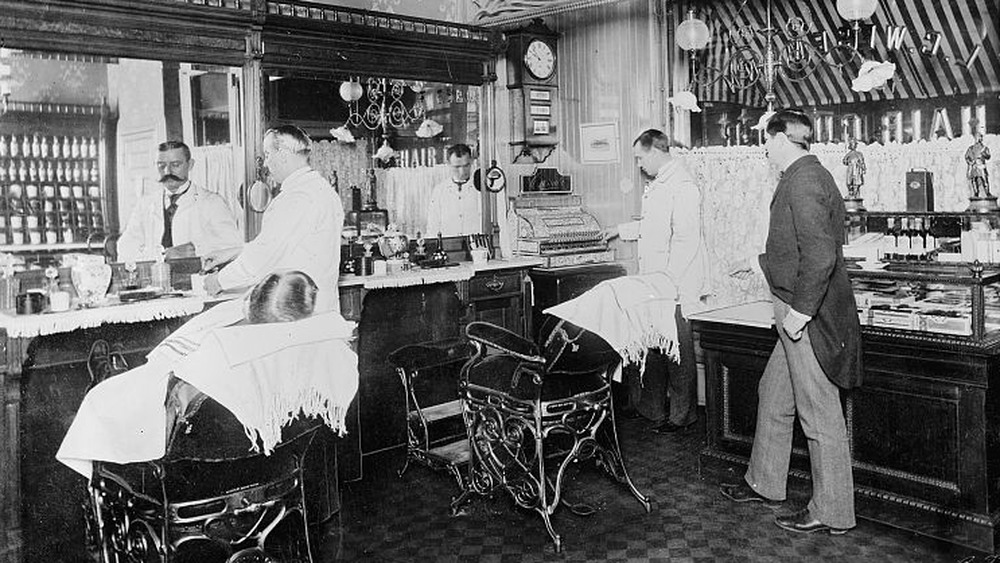

Barbershops offered more than just a shave

Men had lots of other needs besides just getting a trim. Many barbers knew that and subsequently offered as many hygienic services as possible. The more they offered, the more they made. Western Fictioneers confirms that in addition to haircuts and shaves, barbers might also sell cigars, tonics, shampoo, hair dye, and other toiletries. Some even sold guns or offered a "bookie parlor" on the side — anything to get guys through the door. Most familiar to history buffs today are the shoeshine stands which, according to Indiana's Tribune Star, were important in the days of dress shoes but also boots enduring scuffing along the West's dusty trails and unpaved streets.

Important too were bath houses, which began appearing in the West as early as 1852, when California's Calaveras Chronicle noted that "there is nothing more conducive to comfort and health than personal cleanliness." One place in San Francisco even offered rooms "set apart for ladies." These were located in a "Mr. E's" barber saloon on Centre Street. The added service of baths caught on quite quickly. In 1877 T.P. Parnell's new barbershop in Denver offered "hot and cold shower baths at all times" and noted that "prices were down," meaning customers were being given discounts to come give it a try. Advertising for bath services were soon popping up in newspapers across the West. By 1894, places like W.M. Zeek's Benson Bath House and Barbershop in raw and rough Arizona offered baths too.

Barbers knew all the news

Although History By Day states that bathing too often was actually considered unhealthy in the past, stinky cowboys were often in need of a good bath after months out on the range. There were no newspapers out there, and no way to catch up on a local state of affairs. So going to the barbershop was not only a way to clean up but also catch up on what was going on in the world. The Saturday Evening Post cites New York's National Police Gazette as being such a popular source of news that it became known as the "barbershop bible." Even men traveling through town could garner important advice at the barbershop, like where to eat, where to sleep, and where to find female entertainment, says Western Fictioneers.

Frank Bridgeford's Barber Instructor and toilet manual also confirmed that barbers were "constantly surrounded by the current news of the day and always has time to read and keep abreast with the progress of the world." And Marshall Trimble relates that single men (and others) passing through typically followed up with their visit to the barber by perhaps purchasing some fresh clothes, having a nice dinner, and in the Wild West, seeking out a "short-time love affair with a prostitute."

Barbers knew how to keep a secret

There is a scene in the 1960 film, North to Alaska, where an angry Sam McCord (played by John Wayne) wants some information from a man who is at a barbershop. McCord employs all sorts of the barber's torturous tools to exact that information as the barber stands helplessly by. It's a silly scene in a silly movie, but it makes a point: If you wanted information, any information, the barbershop was the place to go. Western Fictioneers explains that barbers not only knew what was going on in the world but also what was going on in their towns — even secret info that few others knew.

The Atlantic expands on the barber's role in knowing everything that was going on. Quoting the Salem Gazette, barbers heard "every flying bit of news," which "seems to come right through his shop window, and to stick to him, like burs to a boy's jacket." In Mississippi, barber William Johnson was one of the very few in his trade who secretly recorded his daily interactions with his customers during the early 1830's. This was of course long before the Wild West era, but Johnson's diaries give an excellent example of the events and actions of others he witnessed every day.

Shave and a haircut, two bits

Barbers serviced men from all trades and walks of life, gave them haircuts, shaves and baths and, according to True West magazine, occasionally extracted their teeth if there was no dentist in town. What did barbers make for their trouble? Well, it depends on where they were.

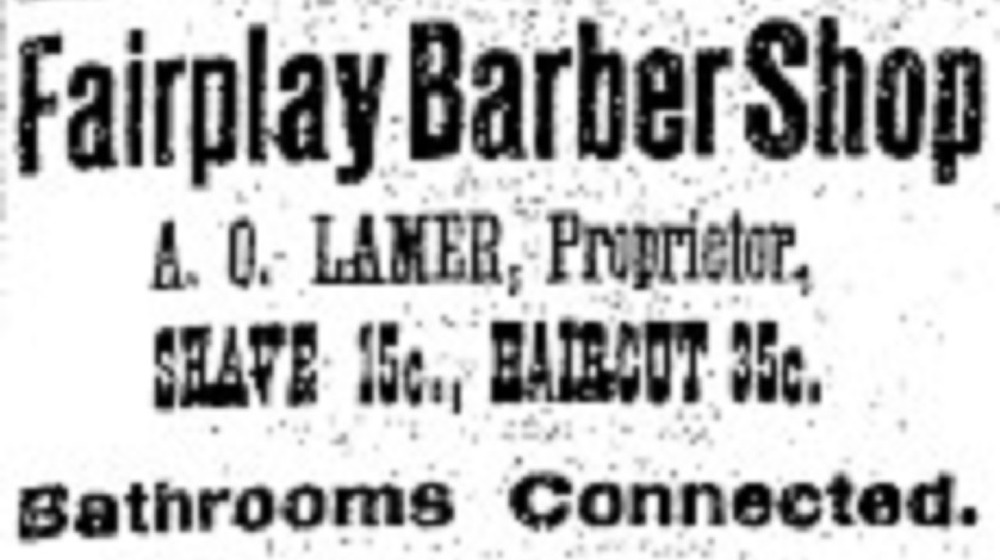

In Kansas, the Fort Scott Daily Monitor (per Kristin Holt) reported in 1870 that a barber named Mortimer was undercutting his competitors by offering the nearly half-price rates of 25-cent haircuts and ten-cent shaves. But around the same time, says Marshall Trimble, men in busy Dodge City could expect to pay 75 cents for a combined shave and a bath.

The National Barber Museum says the average barber in 1880 paid about $20 to stock his shop and charged three cents for a shave and five to ten cents for a haircut. Western Fictioneers elaborates further, citing the "shave and a haircut — two bits" saying, adding that cowboys paid around 50 cents for a freshwater bath or half that if the water had already been used. The price went up on Saturdays, one of the barber's busiest days. By 1899, however, History Nebraska says haircut prices were increasing from ten cents to 15 cents, because barbers rightfully claimed that "a shave, steam for the face, neck shave and a moustache curl is together too much work for a dime."

Barber's Itch and other maladies

If "cleanliness is next to godliness," as the scripture goes, then the hardworking barbers of the West must have had one foot in heaven. But Lord help the barber whose tools were rusty or dirty or who offered less than sanitary conditions for their customers. Doing so could result in "Barber's Itch," defined by Medicine Net as a "superficial fungal infection of the skin" wherever hair on a man could be found. Men's Health lists other barber-caused skin issues too, with such scary names as Folliculitis, Tinea capitis, Impetigo, lice and even tetanus — most of which can be caused by "improperly sanitized combs, scissors, or razors," or even dirty towels.

In the West especially where water could be scarce, the Chudnow Museum verifies that some barbers began using "personal shaving mugs" in a vain attempt to stop fungal infections. What they found, however, was that Barber's Itch was spread from dirty razors, not the community shaving mug. By 1882, newspapers like the Colorado Miner advertised Dr. Frazier's Magic Ointment, which cured a veritable wealth of skin problems, including Barber's Itch. And in 1893, the Colorado Daily Chieftain offered an even simpler solution: mixing your own saliva with the ashes of a "fine Havana cigar" and applying it three times a day. Yuck.

The Black barbershop and why it was important

Long before settlement of the West, black slaves served as barbers to their owners. Booksy confirms enslaved people not only groomed their masters but were also leased to others for that purpose as well. And in the years before and after the Civil War, says author Quincy Mills, the custom was for black barbers to "serve an exclusively white clientele." In the years following the Civil War, however, Western Fictioneers explains that it was fairly easy for a man of color to set up his own barbershop — but although he served both black and white clients, he could not get service in a barbershop owned by a white man.

Even so, black-owned barbershops were extremely similar to those owned by whites. Men in these places, says Collectors Weekly, felt at ease to socialize, discuss the issues at hand, learn the latest news, and receive specialized grooming to suit their natural hair texture, an art which very few white barbers knew. And although unions pushed for licensing laws that prohibited blacks from working as barbers, by the 1890's, African Americans born after the emancipation were able to open barbershops in their communities (per Marketplace). The Black barbers of the east eventually worked their way west, where their population grew steadily for several decades, says AAME.

Female barbers enter the western realm

As early as the 1860's, women began breaking into the man's world of barbering. Western Fictioneers cites one of the first ladies in the profession, a Madame Gardoni, as "doing a thriving business" in Galveston, Texas, in 1867. And in 1870, another woman had set up her barbershop in Detroit, making the news all the way in Kansas. By 1874, according to Oregon's Albany Register, the capital city of Salem had not one but two ladies working in the barbering field. But certain married women took offense to the idea of another woman man-handling their men. In 1874, Washington's Puget Sound Dispatch reported on a lady barber who was run out of Dubuque, Iowa, for making too easy an acquaintance with certain married men.

It is true that some brothels offered shaves and, more intimately, baths. Maybe that's why a New York newspaper (per Kristin Holt) sent a reporter to spy on four young women as they waited on customers. The girls told the writer they had applied to a legitimate help wanted ad and were professionally trained. Still, the Daily Tombstone Epitaph predicted that "divorces will soon be the order of the day" over the presence of a lady barber in 1886. And an 1893 editorial in San Francisco claimed women couldn't even keep their razors sharp. But the women prevailed. One of them in a Colorado town couldn't resist the shock value of beginning her 1902 advertisement with the all-caps greeting, "HELLO KOKOMO!"

Barbershop quartets keep history alive

Places like today's Old West Barbershop in Keller, Texas, try to the keep the history of old-fashioned barbershops alive. It's got to be tough, what with so many modern instruments and creams and soaps that are far better in quality than they were over a century ago. But the quintessential history of barbering is best represented by barbershop quartets, which retain much of their historic flavor today. Britannica states that the history of these four-man musical groups in America is obscure, but historian David Wright was able to trace barbershop singing back to Gregorian times, Elizabethan England, and finally, to America in the mid-1800's. Barbershop quartets likely formed when barbershops served as social centers for the men they served.

Today, barbershop quartets remain a four-person group singing " distinctive four-part chords," according to Classical MPR. Competitions are even held for quartets all over America. Unlike the groups from the Wild West, however, modern-day barbershop quartets can be all male, mixed male and female, or solely women. Also, "the tunes and shtick are changing" from the standard tunes of the past. But history buffs can take solace that to certain folks, like our fictional Norm Peterson on the epic television show Cheers, belting out an old-fashioned song in a barbershop quartet can be quite satisfying.