What Life Was Like For Doctors In The Wild West

Living in the Wild West was no easy task. What with illnesses, disease, injuries, and few viable medicines that actually worked, doctors could only do so much for the unwell masses. NCBI cites the average life span between 1850 and 1880 as just 38.3 to 44 years, increasing between 1880 and 1900 to 39.4 to 47.8 years. Considering that today's infant population can expect to live 78.6 years on average according to Everyday Health, things were indeed a bit bleak for early pioneers. Deadly epidemics such as cholera, malaria, scurvy, and typhoid swept across the West, compounded by potentially fatal illnesses like diphtheria, fevers, influenza, smallpox, and tuberculosis. Add a good dose of everyday violence and other perils, and the early American West seemed like a virtual death trap.

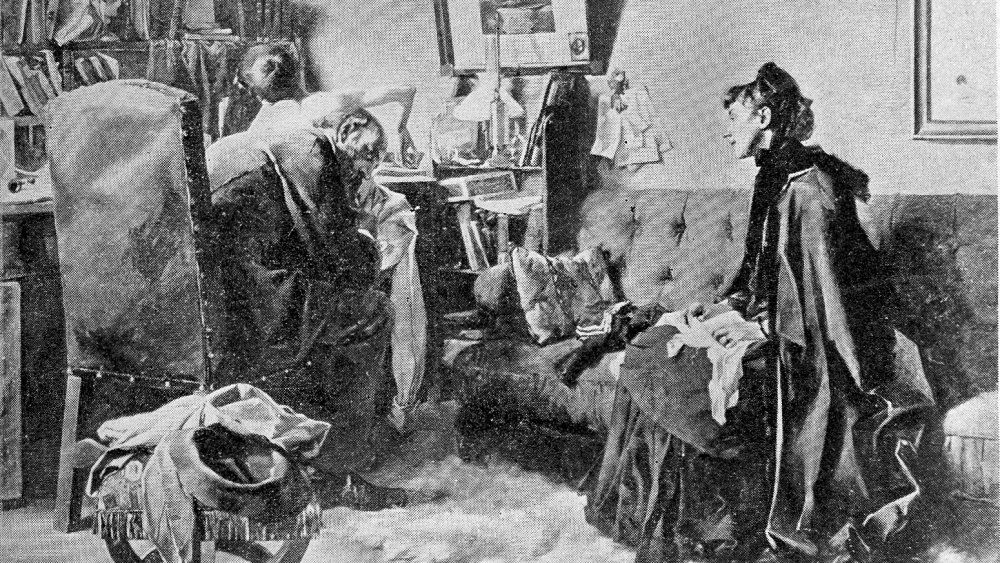

What about the doctors, surgeons, and other healers who did their best to save their many patients? It was certainly no picnic, as seen in the various museums today which feature a typical doctor's office with creepy looking instruments and surgical gadgets. But although physicians primarily kept an office in small towns and settlements, their patients could sometimes be miles away. Yes, life was tough on both ends of the stethoscope. Read on for a taste of life for the frontier doctors in the Wild West.

Some doctors never set foot in medical school

Until the 1860's, there was no medical degree required to be a doctor. American Heritage found that "a frontier doctor was almost any man who called himself one." Only about a quarter of physicians actually held any sort of degree, although many others learned the trade on their own by serving as apprentices. Still others simply called themselves doctors without any qualifications whatsoever. Definitions identifies this latter category as the epitome of the "quack doctors" who either worked solely from their uneducated observations of the patient, or exercised fraudulent practices to make a quick buck. However these healers found their calling, Trips into History reports that the town doctor was often considered "the most educated member of the settlement," also that he might be consulted regularly for advice on politics, the school system, and even legal matters.

Those who found a true calling for the medical trade, according to Heroes, Heroines & History, could easily purchase a fake diploma. But even those who actually attended medical school found it fairly easy to obtain a degree. Even the best universities, namely Harvard Medical School (pictured), did not require written exams of their graduates. As more medical schools opened during the 1870's, students generally attended two four-month sessions a year apart and learned only the basics of anatomy, chemistry, midwifery, physiology, and surgery. Not until about 1900 did medical universities grow more selective of both their students and studies.

A day in the life of the frontier physician

McLennan County Medicine verifies that the doctor's office of the 1800's wasn't much of an office at all, but usually a "shared" room in the back of a pharmacy. Dr. George Goodfellow's office in Tombstone, Arizona was in back of a saloon. Many physicians actually visited patients at their homes, carrying the supplies they needed in the saddlebags on their horses, according to American Heritage. Such important tools as bandages, drugs (or the ingredients to make them), hot water bottles, knives, obstetrical instruments, a stethoscope, saws, and syringes were among the items packed into the bags. Doctors typically left a note with the local pharmacy saying where they were going and when they would be back should they be needed.

Monetarily speaking, being a doctor was often less than profitable. Writer Susan K. Marlowe put the typical doctor's fee at 50 cents for an office call or 50 cents per mile for a house call. Fractures cost $2 to $10 to set, and delivering a baby was $4. But many pioneers had no cash, and the average working-class household made only about $10 per week. In lieu of cash payments, patients often bartered for their care by feeding the doctor's horse or trading services for "produce, services, or goods," according to the Melnick Medical Museum. Even then, the cure at hand was often guesswork, and "kitchen table surgery" to alleviate ailments often produced fatal results.

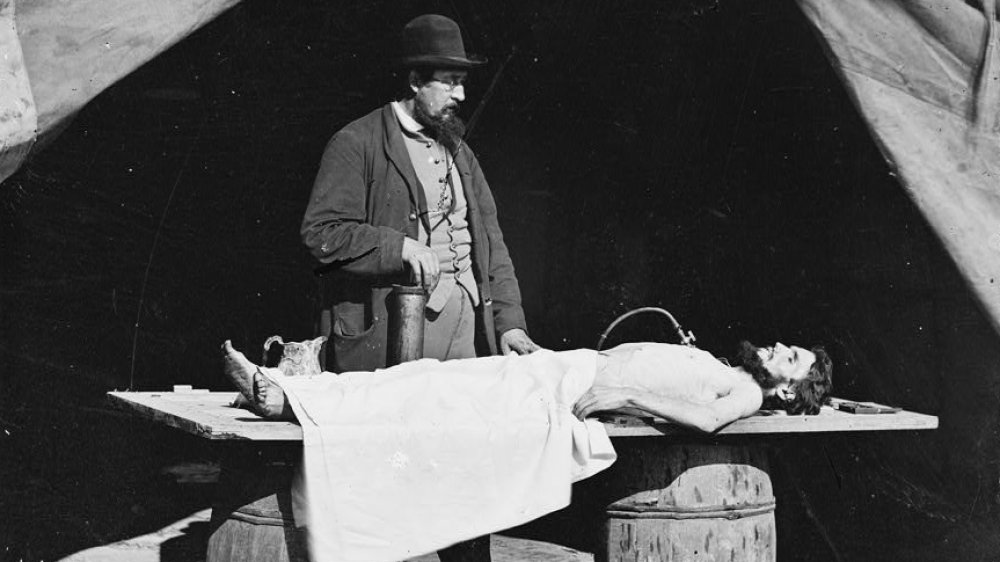

Military doctors were the epitome of unsanitary

The most primitive settings for frontier medicine were the remote forts and field tents where military physicians and surgeons worked, says Trips Into History. Especially on the battlefield, says Heroes, Heroines & History, army doctors often performed amputations sans disinfectant for their tools or anesthesia for their patients. Bullet wounds were especially hard to deal with in the field. Not until 1895, according to Interesting Engineering, did X-rays come into use to find such injuries. Before that, amputation was the most common treatment for battle wounds.

There is no telling how much PTSD the physicians themselves incurred by performing amputations and other grisly work. Surgeon George Miller Sternberg described one doctor who spent the entire night and the next morning amputating "arms below the elbow and legs below the knee in less than five minutes. The deep incision ... the sweeping cut ... pull back the soft parts to expose the bone ... saw swiftly." Physicians also risked their own lives during military skirmishes. Sternberg remembered crawling around a battlefield with his aide as a war was waged against Native Americans. As the men searched for the wounded, they "crept so close to the enemy that they could hear the Indians talking." And following the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, only one of the three doctors on hand during the fight, Dr. Henry Porter, survived.

What didn't kill you made you stronger

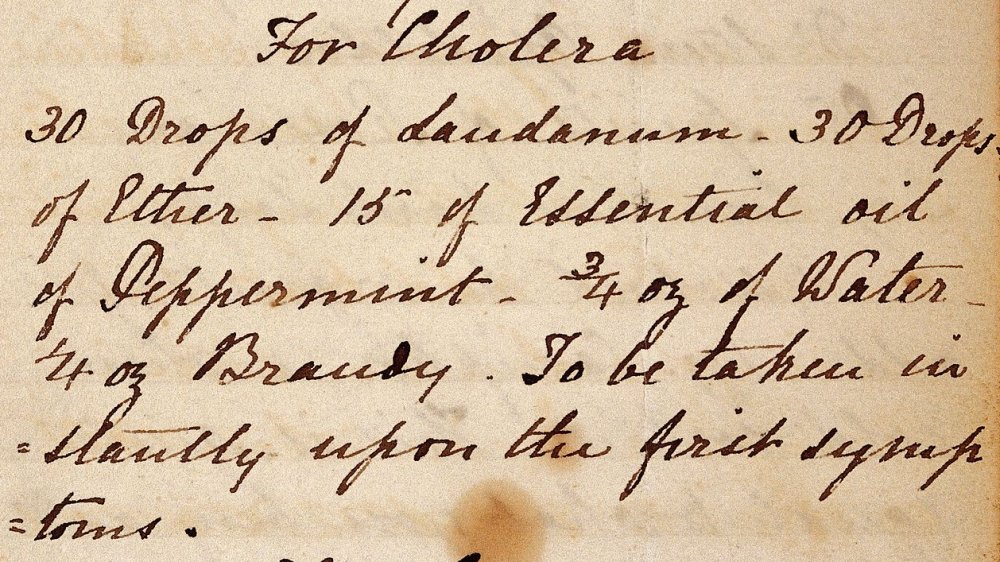

"The remedy is worse than the disease," uttered Francis Bacon of medical practices way back in the 17th century. The saying was still very much true in the 19th century. Although professional physicians took a Hippocratic Oath to do their best by their patients, it was difficult to treat maladies without proper medicine—a rare commodity in the Wild West. Often the best a doctor could do was administer a strong narcotic to kill whatever pain ailed a patient, or purge the illness by inducing vomiting or applying mercury to make their patient salivate—the latter which, according to American Heritage, could cause teeth to fall out.

Another popular but dangerous treatment was bloodletting by laceration or leeches, according to Heroes, Heroines & History. Patients stood the chance of losing too much blood to survive. Or, they could easily overdose on deadly painkillers like laudanum or morphine, says Trips Into History. Not surprisingly, whiskey made a great anesthetic. So did cannabis according to Mental Floss, which counts marijuana among the many herbs doctors used. But Piso's Tablets, which contained cannabis, also included chloroform to help with "women's ailments."

Folk remedies and patent medicines, the bane of physicians

As real doctors used science to work with herbs and chemicals, an older movement promoted folk remedies and patent medicines which might, or more often might not, work. American Heritage, for instance, cites drinking sulfur as being good for you in the 1800's. Snakebites, says author Robin Lee Hatcher, were treated by applying slabs of raw beef, "chicken flesh," or a mixture of vinegar and gunpowder. The latter was also used to stop bleeding cuts, as were wood ashes or cobwebs. And Mrs. Winslow's Soothing Syrup according to Web MD, quieted crying babies with an unhealthy dose of morphine.

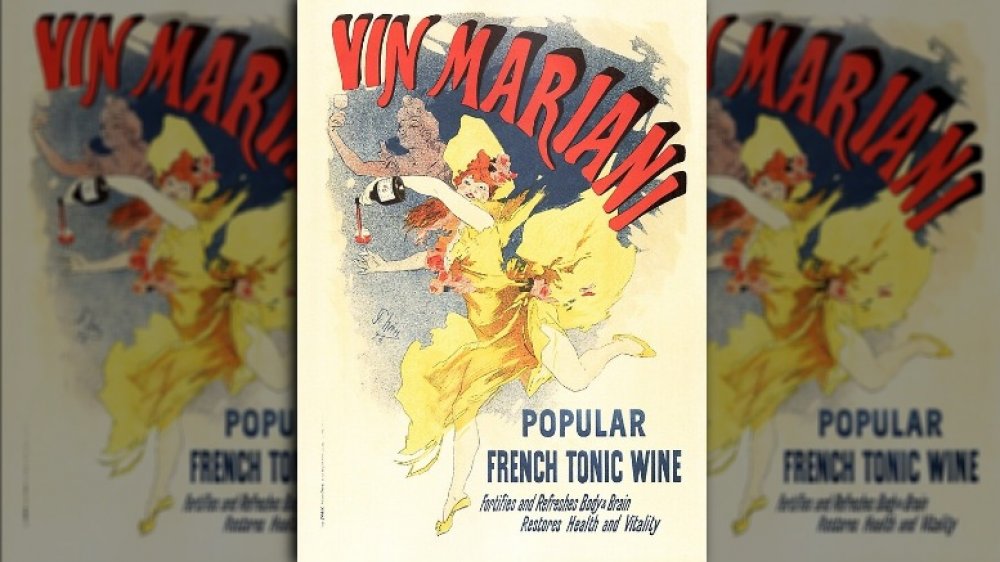

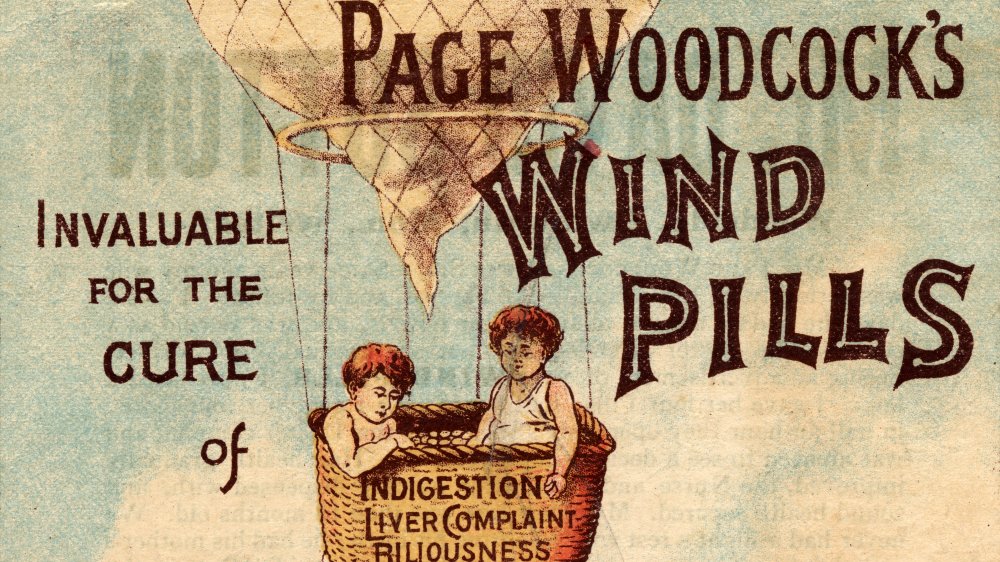

Far more dangerous were the patent medicines sold by street hawkers promoted at Medicine Shows, says Legends of America. According to Hagley Museum, certain local merchants sold them as well. Fairly inexpensive and easy to get, patent medicines came in a variety of forms with colorful names to lure in naive folks who were desperate for a cure. The trouble was, the ingredients were often kept a secret to make the medicines seem almost magical. Many of them included alcohol, cocaine, morphine, or opium, with sometimes deadly results if administered to children. For people suffering from digestive issues, tuberculosis, headaches, or other maladies, however, patent medicines seemed like a welcome cure. Not until 1906 did the Food and Drug Administration demand that ingredients must be listed on the labels of all medicine bottles.

Wine and ketchup for the cure

It was easy enough for some doctors, like J.H. Kellogg, to market certain foods as being medicinal. Kellogg served up his crunchy breakfast cereal to patients at the Battle Creek Sanitarium in Michigan. And Dr. Miles Compound Extract of Tomato, according to The Complete Idiot's Guide to Vitamins and Minerals, aided stomach ailments. Mental Floss has another name for the tomato elixirs of yesteryear: ketchup. Mustard and vinegar also were once regarded as medicines, says writer Tim Lambert—so one could have a hamburger (brought to America in the 1800's, according to What's Cooking in America) with vinegar fries and cure all sorts of ills.

Tonics were also highly popular as elixirs to cure ills. Vin Mariani tonic, for instance, was really a French wine endorsed by the pope, Thomas Edison, and even President Ulysses S. Grant, according to All That's Interesting. Advertising claimed the tonic "fortifies and refreshes body and brain," but the key ingredient was cocaine. Likewise, Coca-Cola also included cocaine in its recipe until it was outlawed in 1914. And Dr. Pepper, invented in 1885 by Texas pharmacist Charles Alderton, was advertised as a "brain tonic." Although the popular soda did not contain any potentially harmful ingredients, the period after "Dr" was left off beginning in the 1900's so people wouldn't think of it as medicine. Today, according to Dr Pepper's website, the refreshment remains "the oldest major soft drink brand in America."

Female complaints, hysteria, and vibrators, oh my!

Hang on to your hats, ladies. An 1880 article in California's Stockton Independent actually submitted that women's "brains are more easily deranged, and unless they change greatly they are apt to deteriorate in essential womanly qualities if thrown much or prominently before the world." What the?! For that reason, delicate damsels of the West, according to Conner Prairie, were relegated to housework and having children. On average in the late 1800's, women gave birth to seven babies, and a third to one half of those children would die before age five. If that wasn't enough to drive a woman mad, being virtually forced to cook and clean with minimal socializing (per Study) would.

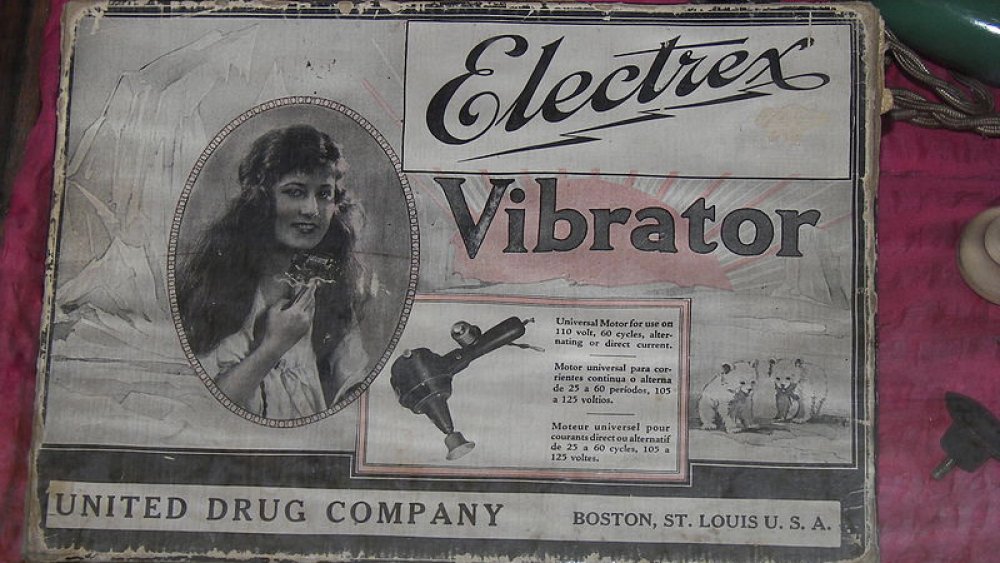

Enter such popular patent medicines like Lydia Pinkham's Women's Tonic, which Legends of America states contained 19 percent alcohol. Mother's little helper indeed helped a little, as well as hair tonics which also contained booze, according to Mental Floss. But overall, male doctors were at a loss as to how to deal with women's histrionics—until Dr. Joseph Mortimer Granville "invented an electromechanical vibrator" in 1883 to cure "muscle aches." History explains that women's "hysteria" was previously treated by Victorian doctors who "manually massaged" women to induce "hysterical paroxysm," otherwise known as an orgasm. Granville's invention now allowed women to treat themselves in the privacy of their own homes. Problem solved.

Female doctors brought a better understanding of women

Who better to know how a woman's body worked than another woman? In a time when men openly defied, ridiculed, and bullied women seeking medical degrees, a healthy handful of them succeeded. Medical News Today credits Elizabeth Blackwell as the first female doctor in the United States in 1849. Another pioneer was Nellie Mattie MacKnight, whose parents actually encouraged her education. In 1891, MacKnight began attending classes amid male students and even professors who seemed downright angry that she wanted a degree in medicine. But MacKnight prevailed, practicing in California for some 40 years.

In 1993, television's Doctor Quinn, Medicine Woman drew another female physician into the deserved limelight: Susan "Doc Susie" Anderson (pictured). Born in Indiana, Anderson endured her parents' acrimonious divorce, a wicked stepmother, being left at the altar, and the death of her beloved brother to pursue her medical degree and go into practice in Cripple Creek, Colorado. Despite contracting tuberculosis during her studies, the good doctor endured mistreatment by her family and worked as a nurse for six years before finding her niche in Fraser, a small town northwest of Denver. The townspeople fell in love with her, but unlike Dr. Quinn, there was no Byron Sully to flirt with. Anderson was still very much single when she died in 1960. She is buried in Cripple Creek.

Beards, impotence, and venereal disease: treatments for men

Although beards are now considered nesting places for germs, there was a time when physicians believed that facial hair was actually healthy. Dr. Alun Withey writes that beginning in 1850, it was thought beards "would capture the impurities before they could get inside the body" and even prevent sore throats.

But doctors also zeroed in on the biggest "moral weakness" for men during the Victorian era: impotence. Surgeon Samuel W. Gross's 1887 book, Practical Treatise on Impotence, Sterility, and Allied Disorders of the Male Sexual Organs, maintained that "masturbation, gonorrhea, sexual excesses, and constant excitement of the genital organs without gratification" could cause impotence.

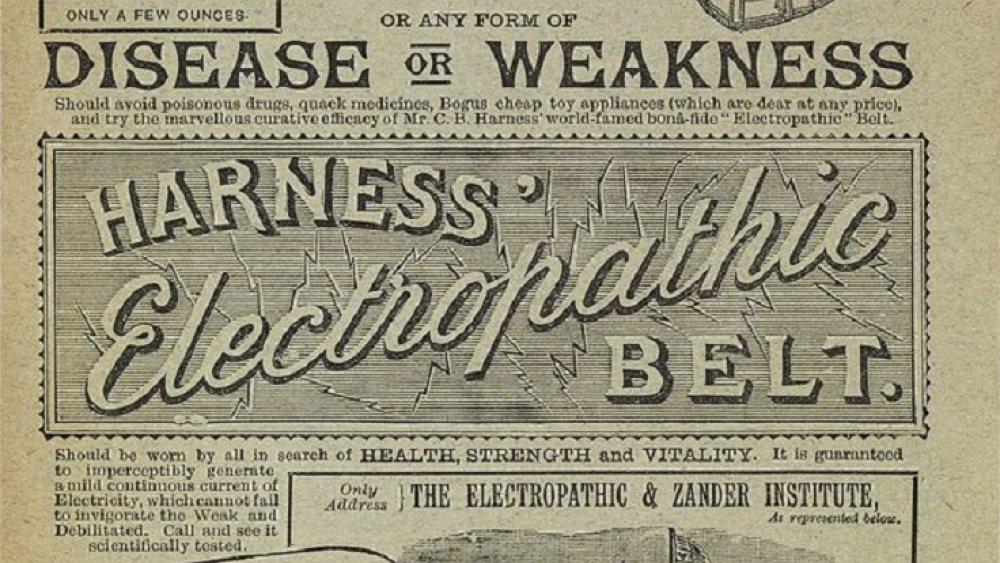

According to History, professional doctors claimed taking a bath "filled with electrodes" would cure impotence, while quack doctors marketed "electropathic belts" for "weak men." But even those who could have sex ran a high risk of contracting sexually transmitted disease. In his paper, "Scratching the Itch: The role of Venereal Disease during the settling of the American Frontier," Joshua Edgar points out that "the constant threat of venereal disease played a major role in shaping the frontier." Whether by sex with prostitutes or other means, men were susceptible to STD's with few actual cures. Bustle talks of "smacking" the genitals (thereby nicknaming Gonorrhea "the clap") and "fumigation" using poisonous mixtures containing arsenic, gold, or silver nitrate. None of them worked.

Drugs, the ultimate treatment for children

Although Health Resources & Services Administration reports that the first children's hospital opened in 1855, that was back in New York. In the primitive West, kids remained subject to questionable medical treatments. Medical News Today theorized that the large number of children everywhere who died during their teething years were given a bevy of lethal treatments to relieve the tooth pain. Doctors commonly applied "bleeding, blistering, and placing leeches on the gums," and even burned the back of the child's head! Beginning in 1898, mothers could give their children Bayer aspirin, but back then the pills were actually laced with heroin, says History. Not until 1924 did the FDA ban heroin from medicines.

Teething aside, "gastrointestinal ills" were the most harmful of ailments to children during the 1880's, says American Heritage. Lack of prenatal care, lack of education about raising children, and poor sanitary conditions, especially among impoverished families and even prostitutes, could lead to dangerous illnesses like cholera, smallpox, and measles. In the drafty, primitive houses of the West, a simple cold could quickly advance to pneumonia. In 1880, according to Statista, 347.49 children out of a thousand died before their fifth birthday. At least smallpox and measles survivors remained free of the illnesses for life; notably, Wild West woman Calamity Jane lived through a bout of smallpox as a child, and so was able to care for others who contracted it in Deadwood, South Dakota.

Aspirin, penicillin, and other modern-day medicines

Thankfully, doctors have always been relentless in their quest to find cures for our ailments. Legends of America notes that certain patent medicines in the Old West really did have curative qualities and are still used today: Listerine was invented in 1879, followed by Milk of Magnesia in 1880. Richardson's Croup and Pneumonia Cure Salve, marketed in the 1890's, is better known today as Vicks VapoRub. Ex-Lax was invented in 1905. And once Bayer removed the heroin from their aspirin tablets, according to CNN, physicians eventually learned that the drug was actually helpful in preventing heart attacks.

Other 19th century cures would come in the form of vaccines for cholera, plague, rabies, and typhoid, although the Center for Disease Control confirms they were not widely used until after 1900. Still, vaccines against measles, polio, smallpox, and other once-deadly diseases have helped reduce their numbers. One of the most important discoveries came along in 1928 when Scottish lab technician Sir Alexander Fleming (pictured) went off on a vacation and left a staphylococcus culture plate sitting out. Fleming returned to find mold on the plate had killed the staph, and penicillin was born.

Old time medical cures are still used today

The physicians of the 19th century West remained relentless in their search for cures, to the effect that some are still in use today. Ohio's Wexner Medical Center lists nitroglycerin for angina and insulin for diabetes as being first used during the 1860's. Electrical engineer Miller Reese Hutchison invented the world's first electric hearing aid in 1895, according to Interesting Engineering.

Even some quack medicine is still in use, like the tapeworm diet, a favorite among Victorian women wishing to lose weight for that hourglass figure they so favored. Healthline confirms that although the practice can be "dangerous and in some cases even lethal," (and there's no real proof it works), it still remains a way some people attempt to thin down.

Britannica attributes one of the most important inventions of the 19th century, anesthesia (pictured), to American doctors Gardner Colton, Charles Jackson, or Horace Wells, depending on the story. And as early as the 1890's, says The Pharmaceutical Century, United States institutions began to manufacture but also inspect "the high volume of vaccines and antitoxins" to make sure they really worked. Today, says Legends of America, we can also thank the 19th century and early 20th century medical profession for Bromo-Seltzer, Doan's Pills, Fletcher's Castoria, and Geritol, as well as Angostura Bitters and even 7-Up which were originally marketed for their medicinal qualities. So drink up, and here's to your health.