The Truth About Koko's Conversational Skills

Koko the gorilla became a worldwide celebrity for her ability to communicate with people via sign language. According to CNN, the western lowland gorilla had some rather exceptional listening skills. She was said to have been able to understand around 2,000 spoken English words by the time of her death in 2018, and could even follow along with people's conversations. She attracted some pretty famous interlocutors during her day, as well. She chatted with celebrities like Mister Rogers and Robin Williams.

Born in 1971 at the San Francisco Zoo, Koko began learning sign language at an early age, and three years later she was taken to Stanford University, where researchers could work more closely with her. They established The Gorilla Foundation in 1976, a nonprofit that works to protect gorillas through research and education on interspecies communication. It also conducted the longest-running study in interspecies communication in history, called "Project Koko."

Koko captured the hearts of people across the world with her sometimes sassy way of signing and the way she cared for her kittens, offering profound insights into the cognitive faculties and emotional landscape of her species. But there was sometimes debate over just how deep her linguistic understanding really was. Did Koko actually "talk," or was her speech a sophisticated way of aping what she saw in those around her? Let's take a look into Koko's communication skills and see just how developed they actually were.

Koko's researchers believed she had a creative and complex understanding of language

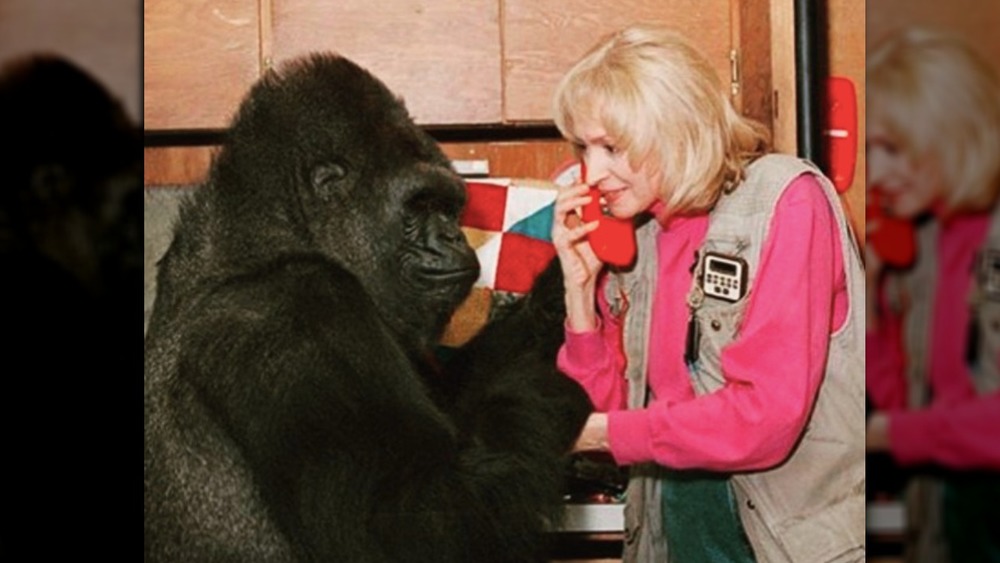

Koko spoke a modified form of sign language that researchers called "Gorilla Sign Language." And according to The Atlantic, she demonstrated creativity and understanding of the language from an early age. When she was just a few years old, she used the word "queen" to refer to herself, something the researchers hadn't taught her to do. "It was a sign we almost never used!" said psychologist Francine Patterson, the researcher taught Koko sign language. "Koko understands that she's special because of all the attention she's had from professors, and caregivers, and the media."

And expressing character traits like vanity wasn't the only way that Koko supposedly demonstrated her mastery of sign language. Writing in National Geographic in 1978, Patterson said that Koko was bright enough to show empathy, argue, and even dole out insults with the language skills she'd learned. She recounted the story of one of her researchers getting into an argument with Koko. The gorilla had used the signs for "bird" and "nut" to insult the researcher. Patterson even said she believed Koko could lie, even though mendacity in a gorilla is quite hard to prove definitively. "When Koko uses language to make a point, to joke, to express her displeasure, or to lie her way out of a jam," Patterson wrote, "then she is exploiting language the way we do as human beings."

But could Koko understand and advocate for action on climate change?

In 2015, The Gorilla Foundation and Noé Conservation teamed up to release a campaign video (posted on YouTube) urging world leaders to take action against climate change at that year's UN Climate Change Conference in Paris. "Man Koko love. Earth Koko love," the gorilla signed. "But Man stupid... Koko cry... Time hurry! Fix Earth! Help Earth!... Protect Earth... Nature see you."

But there was some debate about Koko's knowledge of climate change. Snopes said that her message for climate action was not genuine, that she was merely delivering a message for anthropomorphic effect. It cited a 2014 Slate article that said that the scientific community has yet to come to a consensus about great apes' abilities to express themselves. That article noted that there were dozens of studies similar to Koko's, and that other researchers were unable to achieve the supposed success that Patterson and her cohort had. The studies that didn't make it onto the cover of National Geographic actually led to lawsuits, resignations, and "dysfunctional relationships between humans and apes."

Writing for NPR, biological anthropologist Barbara King said that while she didn't rule out the possibility of an animal like Koko having some of the same thoughts and feelings as a person, this was not the case in the video, which she characterized as a "filmed stunt." She said that even an ape as smart as Koko couldn't "comprehend anything close to the dynamic interplay between humans and nature that underlies anthropogenic climate change."