Lies You Learned In Science Class

It's the ultimate insult. You've spent years studying, memorizing, and taking tests to prove that you understand some of the world's most fundamental workings. You missed television shows, nights out with your friends, and binge-gaming sessions.

You know what? A lot of that stuff you were studying was just wrong. Science, as defined by Merriam-Webster, is "a system of knowledge covering general truths or the operation of general laws especially as obtained and tested through scientific method." But even it's not infallible. Here are some lies you learned in science class.

Diamonds are made from coal

The world is full of incredibly awesome natural phenomena. Unfortunately, the shiniest of these phenomena you learned about as a child does not exist. Diamonds, the story goes, are made from coal that's been subjected to a huge amount of pressure. Superman says so, so it must be true, right?

But according to Dr. Kat Arney and The Naked Scientists, geological studies have shown natural diamonds were actually created about a billion years ago by factors such as temperatures in the thousands of degrees and the kind of pressure you'd feel if you had around 100 miles of earth and rock on top of you. Those forces acted on carbon-rich minerals to form diamonds, and diamonds can also be formed by high-impact strikes caused by meteorites either hitting the Earth or hitting each other in space. What definitely wasn't involved? Coal.

We know coal has nothing to do with diamonds because coal only started forming about 300 million or 400 million years ago (give or take), long after the Earth started making diamonds. In order to get coal, you need plants, and plants didn't happen until about 450 million years ago. That makes diamonds even cooler. It makes your teacher less cool.

Evolution is driven by survival of the fittest and natural selection

When you learned about evolution, chances are your teachers talked about how natural selection and survival of the fittest shaped the world today. If you were the type of student who pointed out something was off because humans still have some major design flaws — like not being able to see in the dark while the lions that wanted to eat our ancestors clearly could — well, your teachers probably told you to shut the heck up. That's because they were teaching it wrong.

According to Princeton biological anthropologist Alan Mann (via io9), survival of the fittest isn't based on how tough or smart a creature is. The important thing is how likely they are to reproduce. Mann says you can look at it this way: "Evolution acts to produce function, not perfection." That's why humans still can't see in the dark, why we still pass on deadly genetic diseases, and why we haven't grown awesome prehensile tails.

UC Berkeley researchers took on ideas about natural selection, and you're wrong there, too. Natural selection isn't about organisms trying to adapt, it's about random genetic mutations that happened to increase odds of reproduction. They also say that "survival of the fit enough" is a better way to think of the process. There you have it — you're not here because your ancestors were the best, but because they were "eh, good enough."

We taste different things with different parts of the tongue

You were probably quizzed on the map of your taste buds before you were old enough to make any inappropriate tongue jokes. You were taught your taste buds were arranged in groups and you tasted different things — bitter, salty, sweet, and sour — in different areas of the tongue. If you were the kid who put a salty pretzel on the tip of your tongue and wondered why you could still taste saltiness, you were right to be skeptical.

The tongue map dates back to 1901, and according to LiveScience, it was the work of a German scientist named D.P. Hanig. He was measuring how sensitive certain areas of the tongue were to certain tastes, and later that turned into the idea that different parts of the tongue only taste certain things. We even know who screwed things up: a Harvard psychology historian with the epic name of Edwin Boring. He transcribed Hanig's data in 1942 but didn't label his graph correctly.

It's wrong for another reason, too, because people also have the ability to taste something called umami. That's not even on the standard tongue map. It's almost as if the tongue is an extremely complex and sensitive object that can't be easily reduced to pithy half-truths.

There are five senses

Quick, name your senses. Taste, touch, smell, hearing, and sight, right? It's so well known that M. Night Shyamalan wrote about "The Sixth Sense" like it was something epic and unheard of, but grown-up science says the five-sense thing is still taught because your dumb kid brain can't understand what your senses really are.

According to psychologists at the University of Glasgow, it was actually Aristotle who came up with the idea of five senses, and while no one is really sure what the right number is, it sure isn't five. The problem comes in defining just what a "sense" is. One answer is that there are only three senses that correspond to the kind of stimuli (chemical, light, and mechanical) our bodies can interpret. Nine is another possibility, and that theory adds mechanoreception (which includes things like balance and muscle stretch), pain, temperature, and interoreceptors (like knowing when you need to pee, when you're thirsty, and when your stomach's had enough and it's time to stop shoving food in your mouth) onto Aristotle's five. Break those nine out into their components, and you can legitimately argue for 21 or 33 senses. Whatever the answer is, it's definitely not five.

All mammals are warm-blooded

Think back to what you were told defines a mammal, and you'll probably remember something about giving birth to live young, having hair or fur, and being warm-blooded. It's in the generally accepted definition of being a mammal, so this one can't possibly be wrong. Can it?

Of course it is, because it turns out teachers lie all the darn time. According to BBC Earth, there are some mammals that bend the definition of warm-blooded to the point of breaking. In case you forgot, warm-blooded creatures maintain a constant body temperature, like a human's toasty 98.6 degrees. But there's a subdivision of mammals no one told you about, animals whose core temperature varies, and not by a small amount. The Arctic ground squirrel (the cute little guy above) has been found to drop its body temperature to 26 degrees, and yes, that means it should freeze solid... but it doesn't. That's an extreme example, but there are other mammals who are clearly not the traditional definition of warm-blooded, like the pygmy mouse lemur and the naked mole rat.

In fact, the very idea of calling something "warm-blooded" has fallen out of fashion with the actual science world. According to The Washington Post, scientists now prefer terms like endothermic (animals that regulate their own body temperature), ectothermic (animals that can't retain body heat), and heterothermic (animals that do a bit of both). Man, was your science teacher wrong.

Dinosaurs were cold-blooded reptiles

If dinosaurs were one of the only things you really paid attention to in class, you're not alone. Dinosaurs are cool. Unfortunately, your knowledge about dinosaurs is built on a lie, starting with the so-called "fact" that they're cold-blooded reptiles.

You can thank John Grady, a biologist from the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, for busting this one. His study (via Nature) examined 381 different animal species and their growth rates, including 21 dinosaurs. He compared how fast a creature grows with its metabolic rates and found that dinosaurs weren't as cold-blooded as thought. They're what Grady's team called mesotherms, and they have the best of both worlds. Cold-blooded creatures move pretty slowly — think of how a crocodile spends most of its day — but a mesotherm dinosaur would have been able to move faster than that. Since they're not as warm-blooded as mammals, they wouldn't have needed as much food to keep them going, another big advantage.

Grady's study isn't without its naysayers, though, and according to Michael D'Emic, a researcher from the Stony Brook University School of Medicine in New York, the data suggested something completely different to him. Per LiveScience, he reanalyzed it to claim most dinosaurs were actually warm-blooded, and Grady agreed to disagree. And, a 2020 Yale study also seemed to lean more heavily toward dinosaurs being warm-blooded after analyzing eggshells of three major dinosaur groups. Either way, they weren't the cold-blooded monsters you were taught.

There are seven colors in the rainbow

"But ... I can see them! Right there! In that picture!" you might be saying. Well, your eyes deceive you. Here's how.

Whenever anyone draws a rainbow, they'll go with seven standard colors: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. But The Telegraph suggests picking seven colors is just the Western world continuing its obsession with seven: days of the week, musical scales, and all that jazz. It was Isaac Newton who decided on seven colors when he was observing rainbows from his self-imposed quarantine outside plague-ridden Cambridge. He added orange and indigo to the previous five. If you go back further, you'll find Greek philosophers said there were three (red, yellow-green, and purple). Homer, for some reason, insisted there was only one color in a rainbow: purple. (No one knows what was up with Homer.)

Not so clear now, is it? The answer is even worse: There's no "real" number to find. The rainbow's shading from one color to the next means there's no definite, solid way to separate one from another. ScienceBlogs worked out the math, using wavelengths to estimate that there are around a million different colors you're actually seeing when you look at a rainbow. And purple is one of them.

There's no gravity in space

You've heard your teachers talk about zero gravity, but it's not a thing. NASA says so! There are actually tiny amounts of gravity everywhere in space. It's what keeps planets safely tucked away in their orbits. Without it, everything would be a mess. What you find in space is more accurately called microgravity.

Rumors about zero gravity seem to be completely reinforced by the pictures of astronauts floating around in their capsules, but that happens because they're actually in free fall, falling around the Earth's horizon. When things are in free fall, gravity makes everyone fall at the same rate and, therefore, seem to float. It's still gravity doing things, we just aren't used to it.

According to Scientific American, you can technically escape gravity, but you'd have to go way, way, way out into the middle of deep space, and there couldn't be any planets, asteroids, or, well, anything at all around you. That's unlikely to happen, and you'd probably be too terrified by the insignificance of your own existence to think about it if it did. Don't grow up to be astronauts, kids.

You only use 10% of your brain

This idea is so prevalent even among adults that entire movies are based on the premise that using more than 10% of your brain will turn you into some sort of superpowered demigod. Those movies are stupid movies.

Scientific American has debunked this entire myth and has possibly even found the source of the idea, if not for the incredibly specific number of 10% — it's a 1907 text called "The Energies of Men." But it's just not true. Now, although our brain makes up a relatively small percentage of our meat-sack, it uses about 20% of the energy we burn. Researchers have used imaging technology to get a peek at which parts of the brain govern which functions, and all of it is used (although not always at the same time) for both conscious and unconscious activities. The brain is even going while sleeping. Mayo Clinic neurologist John Henley erases any doubt: "Evidence would show over a day you use 100% of the brain." Sorry, folks. You've already got all the brainpower you're going to get.

Chameleons change color to blend in with their surroundings

Forget about those Hollywood cartoon chameleons seamlessly morphing into leaves. The reality of these quirky reptiles is far cooler (and slightly less magical). While those vibrant shifts of color might make camouflage seem like their superpower, it's not actually their main act. In fact, they're somewhat like living mood rings, using their abilities not just for self-preservation, but also for communication.

ScIU Indiana University Bloomington explains how chameleons change color due to special skin cells called melanophores and iridophores. Melanophores hold melanin, the pigment responsible for our skin's coloration, which adjusts regularly to allow chameleons to closely match the colors of their immediate surroundings when necessary. Unlike other animals that are equipped with natural defenses such as sharp claws or powerful venom, chameleons lack such weaponry. Instead, their survival hinges on their mesmerizing ability to blend into their environment.

Chameleons adeptly regulate their body temperature by adopting a darker color to absorb more heat when cold while opting for a lighter, paler shade to reflect excess heat in warmer conditions. (Much like other reptiles, chameleons lack the ability to produce their own body heat.) A chameleon's color display plays a significant role not only in camouflage, but also in social interactions. It's like their secret language: A relaxed chameleon might sport a mellow green, while a fired-up male flaunts blues and reds — a flashy advertisement for dominance or a warning to rivals to back off.

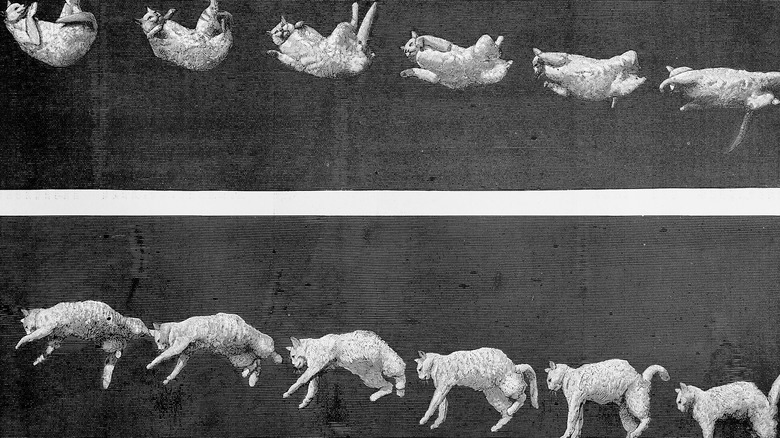

Cats always land on their feet and always do so safely

There's a reason why cats, the agile acrobats of the animal kingdom, possess the reputation of having nine lives. With their uncanny talent for landing on their feet, these feisty felines may seem invincible. But don't be fooled by their flips; that impressive "righting reflex," which they typically hone within seven weeks of birth, comes with limitations.

The righting reflex is a unique ability that helps cats navigate tumbles. With their super-flexible spines (packed with more vertebrae than ours) and an exceptional sense of balance, they instinctively turn mid-air to land on their feet. Researchers have added to this idea with the "bend-and-twist" model, likening the cat's body to two connected cylinders (forming its front and back halves). By bending and twisting these cylinders in opposite directions, the cat's overall spinning motion (angular momentum) cancels out. So, when the cat straightens again, despite starting with no initial spin, it ends up facing an upright direction.

But gravity remains undefeated. As veterinarian Roswitha Steinbacher explained to The Science Explorer: "Sometimes such a plunge has no consequences for the cats. But often, they suffer serious injuries. It mainly depends on the height of the fall. If it is too low, the animals often hit the ground on the side of their body. When cats fall from very high, they can correct their body position and land on their feet." Even then, Steinbacher says, the fall can still cause traumatic injuries.

Goldfish have sucky memories

It's likely that you've heard that bit of "trivia" about goldfish having a memory span of only three seconds or eight seconds. That's shorter than an Instagram story, right? Fortunately, the "brainless goldfish" stereotype is as outdated as floppy disks and fax machines. While these fire-orange finheads might not hold Shakespearean sonnets in their marine memories, goldfish memory banks actually pack a surprising punch.

A 1994 paper published in the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior debunks this theory with an experiment testing eight goldfish. The subjects were trained to press a lever for food during a specific time of day, every day. The timeframe was gradually reduced throughout the week. To the scientists' surprise, even when the food taps ran dry, the goldfish kept faithfully pressing the lever at the usual feeding time. This behavior persisted for several days, showcasing their impressive ability to track and anticipate time.

Professor Felicity Huntingford of the University of Glasgow confirms an interesting fact with BBC: "Goldfish can perform all the kinds of learning that have been described for mammals and birds. And they've become a model system for studying the process of learning and the process of memory formation." In other words, these creatures recognize their feeders, navigate familiar environments, and even distinguish different colors and sounds with attention spans way longer than what's being circulated on the internet.

The Great Wall of China can be clearly seen from space

Listed as one of the seven construction wonders in the world, the Great Wall of China is a dragon snaking across the landscape and a symbol of human resilience etched in earth. But trust us, no matter how hard you try, you won't spot it from a distance as far as space — at least not without some high-powered binoculars.

The Guardian features remarks from Yang Liwei, China's first astronaut, who returned after traveling more than 600,000 kilometers and completing 14 orbits back in 2003: "The scenery was very beautiful," he shared in a televised interview. "But I didn't see the Great Wall." In addition, those who have visited space and gazed back at Earth describe observing mostly an expanse of white clouds and blue seas with specks of vegetation.

According to Scientific American, the wall's visibility from space is surprisingly limited, contrary to its grand reputation here on ground level. Only within a narrow window of low orbit, under specific weather and lighting conditions, does it emerge on machines, telescopes, and satellites. In fact, you'd actually have better luck seeing structures like desert roads from this "orbital perspective" than the famed Great Wall. So, the bottom line is that the "mightiest work of man" isn't the solo standout visible structure from space. It's a bit like trying to find a needle in a haystack — not the easiest task, especially when you're zooming through space at ultra-high speed.

Lightning never strikes twice

We've all seen it in the "Thor" movies: the God of Thunder summoning, well, thunder, followed by a bright, blinding bolt of plasma piercing through the sky. But despite what conventional wisdom tells us, does lightning ever revisit the same spot? The answer is quite shocking (pun absolutely intended).

Science Daily discussed the findings of a 2019 study about the tiny, short-lived, needle-like structures found within thunderclouds. Imagine them as microscopic lightning rods, storing up electricity until they burst, sending out little lightning "fingers" that we usually miss with our clunky detection systems. Of course, just because we can't see the entire process doesn't mean it isn't happening. Take the Empire State Building, for example. Per estimates from the historical structure's official website, this lightning magnet gets struck an average of 25 times a year, with some bolts likely revisiting the same antenna or spire multiple times within a single storm. To explain this, physics professor Dr. Christopher S. Baird shared (via West Texas A&M University) the phenomenon that lighting tends to hit both the tallest and sharpest structures present in an area. This can be explained by the notion that electrical currents are mostly drawn to the path of least resistance.

That said, the next time you find yourself under a rumbling sky, don't let a false sense of security lull you into complacency (per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Seek shelter, unplug those electronics, and avoid contact with water or conductive materials.

If you pick up dropped food within 5 seconds, it's still safe to eat

Over the years, you've probably come across the five-second rule (or some variation thereof), which basically says that if you're able to pick up food that has dropped on the floor within five seconds, you won't give nasty germs enough time to make your sandwich or slice of cake unsafe to eat. But while the idea of snatching that rogue french fry from the floor and declaring it germ-free sounds tempting, the reality is more complicated than it seems.

Healthline asserts that several factors contribute to the severity of cross-contamination (and thus, the likelihood of contracting a foodborne illness). These include, but are not limited to, moisture, the surface type, and the duration of contact with the ground. While most healthy adults might be relatively safe in specific scenarios, the situation differs for young children, pregnant women, and older adults, as they face an increased risk of developing complications from consuming contaminated food.

Based on observations from a 2016 study published in Applied and Environmental Microbiology, researchers found that transfer rates of the bacteria Enterobacter aerogenes are higher in moist foods like watermelon compared to dry foods like crackers. Similarly, longer contact times lead to increased transfers across all types of food and surfaces. Regardless, the bottom line is clear: Any contact with a surface is an open invitation for microscopic hitchhikers. Just toss the fallen food, and your stomach will thank you later.

Water itself conducts electricity

Make no mistake: We're not saying that water and electricity are perfectly safe to mix. Together, they can certainly spark trouble — but it's important to understand why.

As discussed by Science ABC, water is an excellent solvent, and when it contains dissolved elements (e.g., sediments, chemicals, and minerals), it becomes a good conductor of electricity. On the other hand, when water is pure and doesn't have any of these substances, it's actually a really good insulator, as it lacks the ions that allow the movement of charges to take place. Yale chemistry professor Mark Johnson explains the process behind this phenomenon, the Grotthuss mechanism, via Science Alert: "The oxygen atoms don't need to move much at all. It is kind of like Newton's cradle — the child's toy with a line of steel balls, each one suspended by a string. If you lift one ball so that it strikes the line, only the end ball moves away, leaving the others unperturbed."

Of course, in reality, it is nearly impossible to find water that is absolutely free of all impurities. Per the USGS, even the smallest amounts of salts (such as common table salt) in a water solution will allow it to conduct electricity due to the presence of cations and anions. Perhaps more interestingly, when water contains higher concentrations of solutes and ions (like seawater, for instance), it becomes such an excellent conductor that electrical currents might bypass comparatively inferior ones (like the human body) entirely.

Glass is a solid

The story of glass isn't as clear as it seems. Imagine a world where Lego bricks didn't snap into perfect rows but instead merged into a colorful, shapeless blob. That's the world of amorphous solids, and glass is its crown jewel. Unlike its crystalline cousins with their neat, orderly atomic arrangements, glass throws the rulebook out the window.

During the transition from liquid to solid states in most materials, molecules swiftly reorganize themselves, forming a repeating knit pattern known as "long-range order." Per an explainer from New Scientist, the transition for glass doesn't work this way. Rather than an abrupt shift, the molecules' motion gradually decelerates as the temperature decreases. In return, this preserves the "structural disorder" inherent to a liquid while looking and behaving like a solid (as far as the human eye is concerned).

Scientific American provides a more in-depth look at the transformation process. Glass manufacturing begins with rapidly cooling a (typically silica-laced) material from its liquid state. But the material doesn't harden instantly; instead, it enters a supercooled liquid phase, or in simpler terms, an "intermediate state between liquid and glass." Further cooling below the glass-transition temperature slows molecular movement, causing the material to transform into the glass we're all familiar with.

Mammals were nothing but dinosaur prey

Picture the prehistoric world, back when dinosaurs were roaming the Earth. Even the little ones were impressive, right? They were top dogs for sure, and mammals were sort of nature's rejects.

However, in 2005, researchers in China made a discovery that completely changed everything we thought we knew about the relationship between mammals and dinosaurs. They coexisted during the Mesozoic era — between 248 million and 65 million years ago — and people always sort of thought all mammals were just trying not to be dinner. But according to National Geographic, the specimens found in China were diners, not dinners. They're Repenomamus robustus and Repenomamus giganticus, and they were found to have been eating dinosaurs. They weren't the little rat-like creatures usually thought of, either — R. giganticus was about 3 feet long and weighed around 30 pounds. They were predators, and dinosaurs were the prey.

These two might not have been the only dinosaur-eating mammals out there. According to LiveScience, close examination of prehistoric mammal teeth suggests they were climbing their way up millions of years before the dinosaurs were wiped away, which should make the next "Jurassic Park" a very different movie, indeed.

Newton discovered gravity because an apple hit him on the head

The illustration is iconic at this point: Isaac Newton, sporting his signature hairdo and lounging beneath an apple tree, suddenly gets bonked on the head by a juicy projectile, and is instantly struck with an epiphany about the nature of gravity. It's a scene etched in our collective memory. But when placed under historical scrutiny, this version of the story is like a half-baked apple soufflé: it might taste good, but it doesn't quite hold its form.

While written records suggest an apple did indeed play a role in Newton's journey toward gravity, it never landed on his head. As New Scientist explains, the truth is hidden in a manuscript titled "Memoirs of Sir Isaac Newton's Life," published in 1752 by pioneering Newton biographer William Stukeley. As the passage goes: "It was occasion'd by the fall of an apple, as he sat in contemplative mood. Why should that apple always descend perpendicularly to the ground, thought he to himself..." This observation, of course, was what sparked Newton's ponderings about the revolutionary universal law of gravitation. As for the apple-on-Newton's-head story, though — it's pretty much applecr–, er, apocryphal.

Space is cold enough to instantly freeze you to death without a spacesuit

The notion that space itself is cold is a common misconception. Addressing this claim, Harvard discusses that the reality is actually more nuanced, as space itself has no temperature. Temperature measures the movement of particles, but since space is mostly a vacuum, it is a near-empty expanse with barely any particles to jostle.

With that said, the things we can find in space do have temperatures. Per estimates from experts, the temperatures of the densest clouds found within the interstellar medium — the gaps between the stars where one can detect particles and gases — can dip as low as -505 degrees Fahrenheit. Meanwhile, less dense ones can reach about -279 degrees Fahrenheit. Still, even if you were ejected into deep space without a spacesuit, you instantly freezing to death simply won't happen, since thermal radiation alone won't sufficiently speed up the heat transfer process (per Harvard).

That's not to say, of course, that the cold won't eventually get to you. As Jim Sowell, an astronomer from the Georgia Institute of Technology, explained to Popular Mechanics: "You can have high-speed particles zipping by us outside the Earth's atmosphere, but if you took off your spacesuit, you would feel cold because there aren't that many particles hitting you." Still, the far more likely (and perhaps much more terrifying) reality is that your spacesuit-free outer-space demise will be due to plain ol' air deprivation.

Bananas grow from trees

Peel back the yellow skin of a banana, and you expect to find... well, a banana, right? But beneath that sunkissed sweetness lies a botanical double agent, hiding sugary secrets. The banana tree, as most people may call it, isn't a tree at all — and the banana itself is actually a berry in disguise.

Technically speaking, the banana plant is an herb. As expert Himani Saklani from the Forest Research Institute explained (via Science ABC): "What you call a tree isn't actually a tree, but an herb. Just like mint, grass, and rosemary, the banana plant is also an herb." Per the article, herbs are characterized by their soft, delicate foliage and lack of hemicellulose and lignin (which influence the "woody" characteristic of the tree trunks we're all familiar with). On top of that, these herbaceous plants typically complete their life cycle annually and biannually (within one or two growing seasons), although some may persist for several years.

In line with this, botanist Julia Morton writes in her book Fruits of Warm Climates that the term "banana" encompasses diverse plant species and hybrids within the genus Musa of the Musaceae family. The fruits that these species produce have seeds and fleshy layers, and come from the single ovary of a single flower; in other words, they're berries, despite not being a visual fit for the traditional image of a berry (via FlipScience).

Black holes are funnel-shaped and crush everything

Black holes are one of the most mysterious, confusing phenomena in the universe, so it goes without saying there's a lot we don't know about them. Some things are certain, though, but when that gets translated into grade-school level... well, no one's perfect.

First, let's take a look at the idea they're funnel-shaped. You probably saw that drawing in your textbooks, but it's totally wrong. Kind of. According to Discover Magazine, they're actually spherical. That funnel shape you see drawn all the time is actually an attempt to depict the three-dimensional phenomenon of bending gravity in the two dimensions on your piece of paper. A little weird, but just remember: spherical.

Now, the crushing thing. Were you taught that anything passing a black hole's event horizon is sucked in and crushed under its insane gravity? It's the opposite: Things get stretched out. Black holes can be massive, and their density means there's a huge difference in gravitational pull even across relatively short spaces — say, for example, your 6-foot self. It's such a drastic change that if you're swimming toward a black hole, your head is going to feel hundreds of millions of times more gravity than your feet, and that's going to stretch you — not crush you — in a process called "spaghettification." No wonder your teachers lied.

It takes more muscles to frown than to smile

It's time to settle this, once and for all: Does it really take fewer muscles to smile than to frown? Well, what constitutes a "real" smile is subjective — and to complicate matters further, we don't all have an equal number of facial muscles at our disposal.

First, let's dispel the myth of a standardized facial map. Per Nature, our faces are actually more unique than we realize. Research shows we can have anywhere between 14 and 22 individual muscles dedicated to contorting our faces. So, the number needed for a smile or a frown can vary from person to person, adding a dash of mystery to the equation. Following this, Live Science emphasizes that comparing "true" and "false" smiles is a challenging task with somewhat confusing parameters. Plus, smiles can express many emotions beyond just happiness, and whether each emotion has its own unique facial muscle map is still debated to this day.

To provide a more quantitative analysis, David H. Song, a plastic surgeon at the University of Chicago Hospitals, shares a detailed list of all the relevant facial muscles with The Straight Dope. Based on the provided count, it takes a grand total of 12 principal muscles for a full smile; meanwhile, frowning only requires 11. But here's the twist: Despite needing more muscles, smiling actually takes less effort, since human beings have the inherent tendency to smile more often, leading to better-trained muscles.

Hair and nails keep growing after a person dies

Like a scene straight out of a Tim Burton film, people have long claimed that post-death growth of hair and nails actually happens. Spooky, right? But the truth is actually simpler than you might expect (and far less creepy).

According to forensic anthropologist William Maples, "It is a powerful, disturbing image, but it is pure moonshine. No such thing occurs." A 2023 article published via StatPearls states that the average growth rate of human hair is estimated at up to 6 inches each year, fueled by a growth of 0.01 inches per day. With that said, BBC straightforwardly states that cells have varying lifespans. Once a person's cardiac activity slows to a halt, oxygen ceases to reach the brain at a steady rate. Consequently, nerve cells die in less than 10 minutes, since they lack glucose reserves. Meanwhile, skin cells have a longer lifespan, allowing for successful grafts even when harvested up to 12 hours after death.

Live Science further explains that the illusion of increased hair and nail length stems from postmortem dehydration. In simpler terms, it's when the body loses water and dries up, which causes the surrounding skin to retract. This exposes previously hidden portions of hair and nails, making them appear longer while their actual growth has ceased due to the absence of vital hormonal regulation.

There's such a thing as the missing link

You learned a lot about evolution and Charles Darwin's theories, but unfortunately, you were taught all kinds of lies. Let's just talk about one piece of the evolutionary puzzle here: the missing link.

Anthropologist Cameron McPherson Smith and author Charles Sullivan explain what's going on in this one (via Skeptical Inquirer). The term "missing link" suggests there's an individual animal that fills in a gap between an organism with one set of traits and the "future" version of that same organism, but that's not how evolution works. At all. Contrary to our theories a few hundred years ago, species aren't arranged in neat "chains" or "trees." Lots of things have changed in 400 years, but while we had no problem giving up outhouses, we've clung to this outdated idea of a missing link. Instead of thinking of evolution as a chain, think of it more as colors. Smith and Sullivan say the better way to explain evolution is in shades, so let's do that. Take a crayon. Start coloring, but make it darker and darker as you go on. At some point, that pink is going to become red, and it's sort of the same color, but not. See?

There's no one color that bridges the gap between pink and red, like there's no one missing link that connects modern species to their ancient ancestors. Now, please excuse us. This space-faring dinosaur getting sucked into a black hole isn't going to draw itself.