The Murder Of Catherine Cesnik, The Nun Who Knew Too Much

It's one of those terrible truths of the world that bad things happen to good people. No matter how wrong it seems, it's happened too many times, and the case of Sister Catherine Cesnik is one of those examples. Born in Pittsburgh, Penn., in 1942, reports the Baltimore Sun, Cesnik was described by her younger sister as devoted and rather ambitious. The sisters were incredibly close, even after Cesnik felt that God had called out to her to become a nun. But, on top of that, she had a natural gift for teaching. She left for Baltimore at 18 to join the School Sisters of Notre Dame, eventually going on to teach at Archbishop Keough High School.

But she wasn't fully happy there, and by 1969, at the age of 26, Cesnik knew she had potential that her order was stifling, knew she could become so much more, and moved out to take a job at Western High School. Ghosts of the past might've followed her, though, punishing her for what she knew and the good she did.

Nov. 7, 1969, seemed like a normal night for Catherine Cesnik

For all the press and notoriety that this case would get in the long run, it started out exceedingly normal. According to the Baltimore Sun, as evening fell on Nov. 7, 1969, Sister Catherine Cesnik left her unassuming apartment, heading to the Edmondson Village Shopping Center around 7:30 p.m. As far as her roommate, Sister Helen Russell Phillips, could tell, she was headed out to buy an engagement gift for her sister, as well as run a few errands.

Another article put out by the Baltimore Sun tried to paint a clearer image of the evening. At some point — probably the first thing on her trip — Cesnik stopped by a Catonsville bank and cashed a check for $255, part of a pretty regular routine. Either she or Phillips would always make to stop on every second Friday to cash their paychecks. After that, it seemed like she paid a visit to Muhly's Bakery inside the Hecht Company store in Edmondson Village.

But that's where things get hazy. No one really knows exactly what happened to Cesnik. Phillips never saw her roommate again after she left that evening, and even a store clerk couldn't confirm Cesnik's presence there that night.

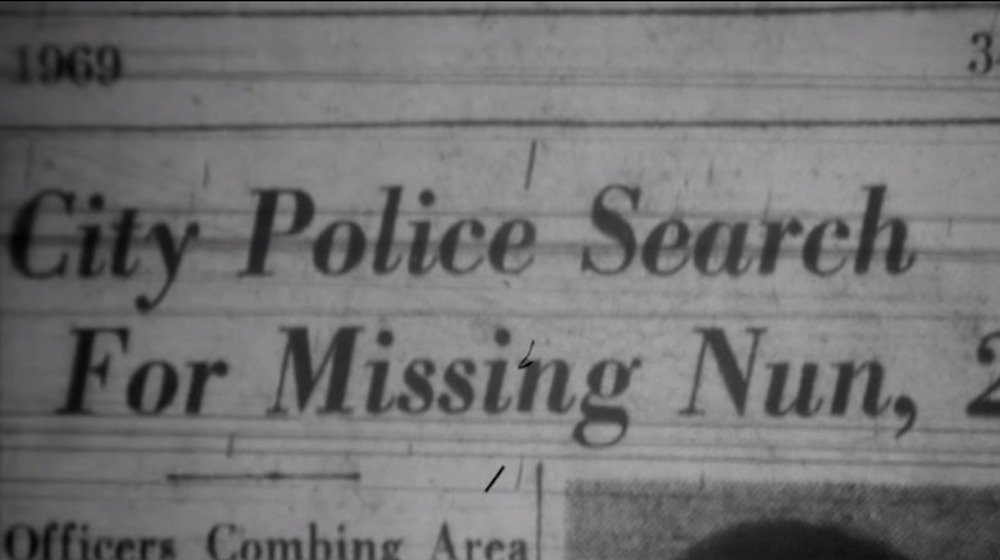

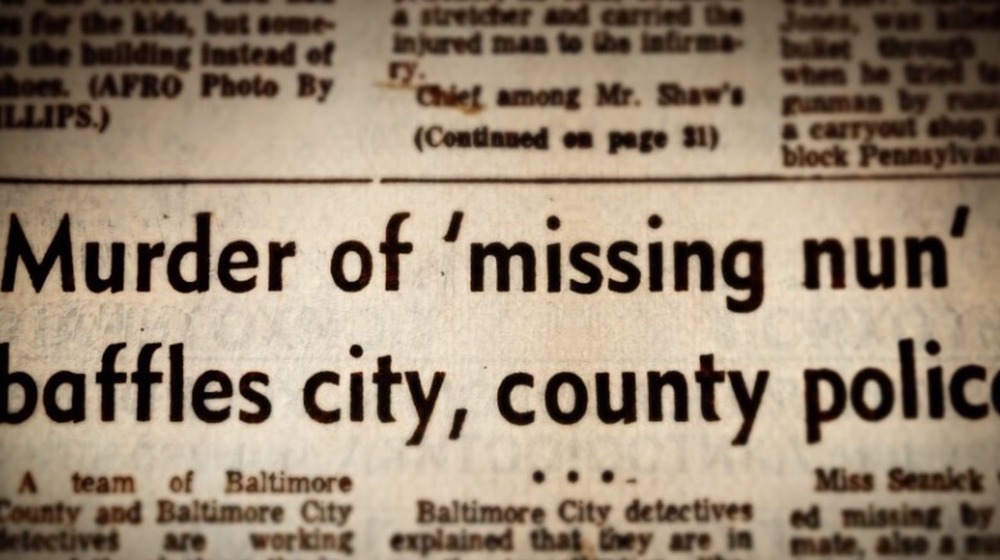

Catherine Cesnik's disappearance scared a lot of people

As the next morning rolled around, Catherine Cesnik still hadn't returned to the apartment, and her roommate became very concerned. Something was clearly wrong, and so, according to the Baltimore Sun, Helen Russell Phillips called on the help of a few friends — revs. Peter McKeon and Gerard J. Koob. They got in touch with the local police, reporting that Cesnik had gone missing.

The news shook a lot of people, to put it lightly. Stories shared by Capital Gazette showed that Cesnik was thought of fondly by all the people she'd worked with, despite being a teacher at Western High School for only a couple months. Her co-workers had kind words to say about her. Western's principal noted that she was an especially "fine teacher," while others pointed out that she was known for her compassion.

And it was the students who really benefited from that, as Huffpost describes. She was warm and energetic, always ready to engage with her students, writing musicals for them to perform on stage, or inventing games to encourage them to teach each other new vocabulary. Beyond just being a generically good teacher, she even let her students drop by her apartment on weekends for a chat or a bit of music. It was no wonder that in the wake of the news, the students were all quietly shocked, worried that the police might stop looking for her.

Catherine Cesnik's car painted a strange scene

The first clue in the disappearance was found pretty early — her car ended up giving some insight into what happened but mostly brought more confusion.

The Baltimore Sun explained that Rev. Peter McKeon (possibly with Sister Helen Phillips and Rev. Gerard Koob — it depends on the report) found her car unlocked around 4:40 a.m. on the day after her disappearance. The green 1970 Maverick had been parked illegally near the apartment. A little more digging brought with it the fact that neighbors had seen the car parked there since 10:30 p.m., though it had been in her assigned parking spot behind the building just two hours earlier (via Baltimore Sun).

Inside, a bakery box filled with buns sat on the front seat (probably from Edmondson Village), along with some leaves and twigs. A few more branches were caught on the radio antenna, while another twig was found stuck to the turn signal lever on the steering wheel, a piece of yellow thread caught onto it. Crime Museum adds that the car itself was newly caked in mud.

Really, the whole thing raises a lot of questions, summarized by Huffpost. The car was parked illegally but only a block away from the apartment, and there were no signs of struggle. So it probably wasn't the result of some random act of violence. Instead, it made more sense if someone Catherine Cesnik already knew coerced her from the car.

Eventually, Catherine Cesnik's body was found

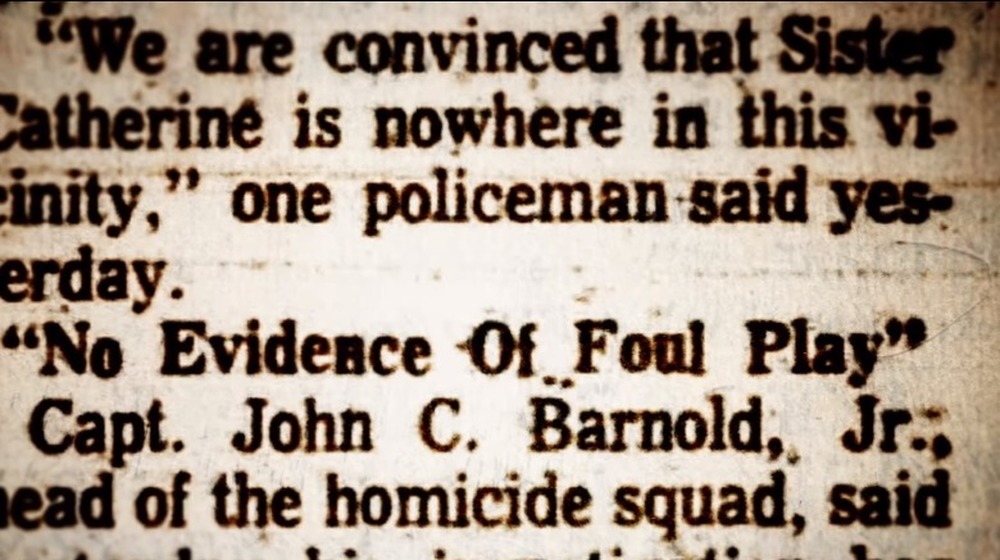

With twigs and branches found in the car, police thought that they might have a pretty good lead, as the Baltimore Sun explained. It made sense that she'd gone into some kind of wooded area, and with Leakin Park near where the car was found, it was a place to start. And to end. A search of the park turned up nothing, and there was no lead on her whereabouts for almost two months.

Jan. 3, 1970, changed that. According to Crime Museum, a hunter and his son found Catherine Cesnik's body at an informal garbage dump in Landsowne, Md. (just outside Baltimore), covered in snow and partially hidden by a nearby embankment. The exact area couldn't actually be reached by car, meaning that she would've been forced to walk there, or possibly carried. It's hard to say what's true. Huffpost added that choke marks colored her neck, and a quarter-sized hole in the back of her skull pointed to her actual cause of death — blunt force trauma, leading to a skull fracture and brain hemorrhaging. The weapon that caused it? Still a mystery.

There were a couple people of interest

Potential suspects seem like they should shed some light on a case, but that wasn't the case here, as Huffpost documents.

Gerard Koob was an initial person of interest. One of the friends Helen Phillips had called upon, Koob had been dating Catherine Cesnik at the time. He later became a Methodist minister, but before that (and before Cesnik had taken her final vows as a nun), he'd asked her to marry him. She'd said no, but they still kept writing love letters and spending time together. Shortly before her disappearance, he'd called her again, telling her that he was still in love with her. He'd even leave his position as a priest and marry her, if only she would agree.

But that lead didn't go anywhere. Koob had an alibi for the night — he'd been out at a movie with another priest — and claimed not to know anything. Investigators didn't really buy that, thinking that he knew more than he let on, but the church forced them to stop searching.

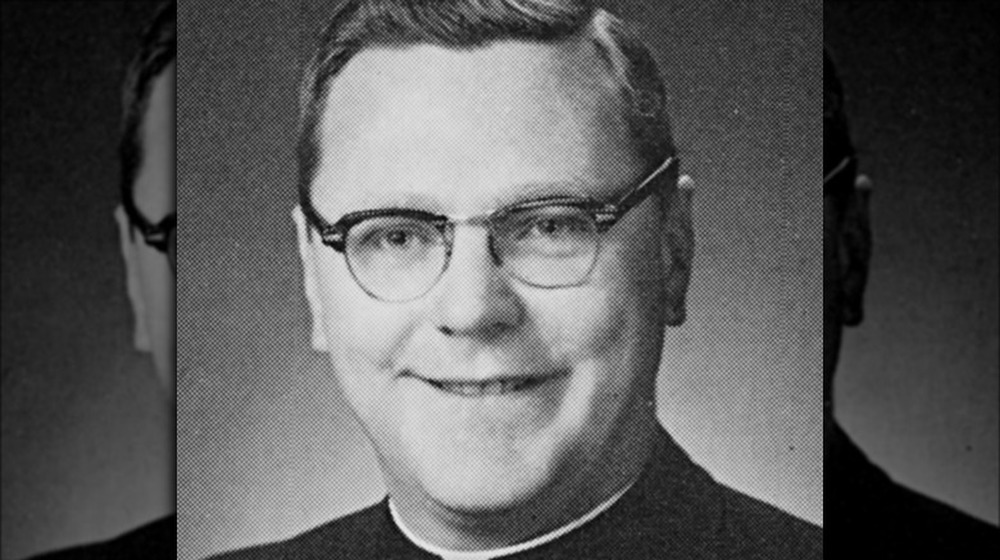

Detective Nick Giangrasso still thought it was someone tied to the church, though, and began to look into Father A. Joseph Maskell. It was a name he kept hearing in interviews with other priests, and the man had worked with Cesnik while she taught at Keough. But, again, that didn't go anywhere, with Maskell always conveniently too busy to talk.

Allegations came out against Joseph Maskell

Father A. Joseph Maskell was a person of interest for a reason, it seemed. Outwardly, it seemed like there was little wrong with him. Rather, people actually trusted him a lot, reports Huffpost. In his late 20s at the time and described as pretty charismatic, he was easy to like, working as a counselor with a psychology degree from Johns Hopkins. Many of the parents in the area would regularly attend his masses and let him baptize their children. And when those kids got older, Maskell would give them rides home or to appointments.

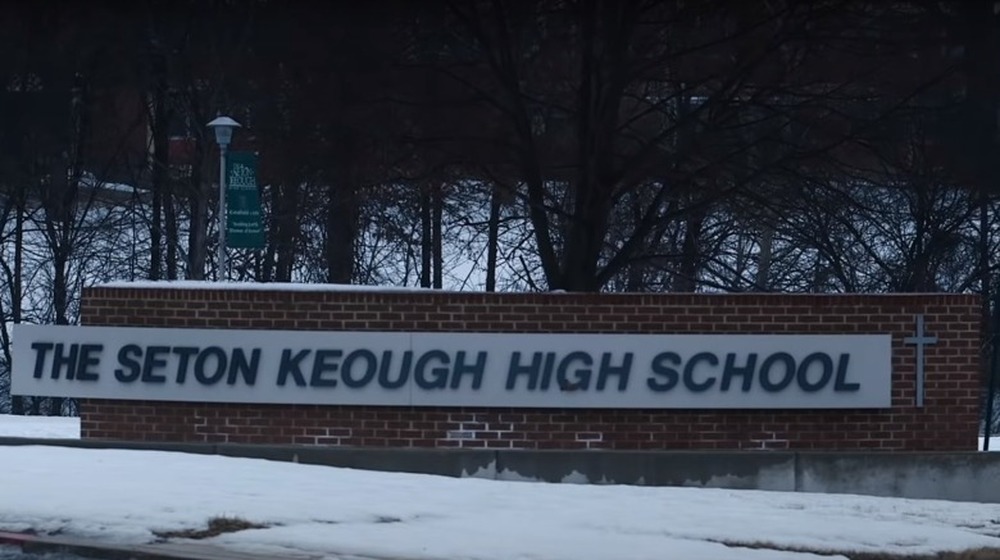

But that charming façade was shattered in 1992. Two women — anonymous at the time but who later came forward as Jean Wehner and Teresa Lancaster — came forward with allegations of abuse, saying he (and some of his associates) had assaulted them while they were students at Archbishop Keough (later Seton Keough) High School (via Baltimore Sun). It didn't take long for him to lose his position as a pastor, spending some time in a psychiatric hospital (though he was released shortly after, apparently perfectly fit to work at another church). By 1994, over a dozen allegations had been filed against Maskell by different women, some of whom had been abused, and others who had managed to fend off Maskell's advances.

The stories the women told were awful

The women have since been more vocal about the abuses they suffered at Joseph Maskell's hands, and all the stories are universally awful (via Huffpost). In general, he exploited 1960s counterculture, offering a relaxed environment and a willing ear regarding sex, drugs, alcohol, and the like — all things that the students' strictly religious parents detested. He'd mostly target students who were struggling, either academically or at home, calling them in for "therapy," where he used his charms to manipulate them into believing he knew what was best for them.

And that often involved stripping them of their clothes, touching them in his "godly manner," or forcing them to pose for nude photos while he and the school's religious director watched with, well...unrestrained pleasure. Teresa Lancaster also mentioned times when he would take them to a gynecologist — Dr. Christian Richter — for check-ups, during which he would occasionally assault them on the table (Richter would later deny being a part of the abuse). It was apparently a fixation for Maskell, who would then perform his own mock "exams" on the girls, flaunting his authority and power.

Other times, he would arrange full pseudo brothels. Some of the women recalled feeling drugged during those events, during which Maskell would basically share them with his friends as he saw fit. Friends which, reportedly, also included uniformed police officers. The details go on, and none of them are pretty.

Many of the girls went to Catherine Cesnik for help

In a school where a number of the teachers seemed to know Joseph Maskell was "weird" but sent students to him at his request, Catherine Cesnik offered a light in a very dark, twisted place. She acted like a savior to his victims, and Huffpost compiled a number of those stories.

While she was still working at Keough, she definitely had some idea of what Maskell was doing, and when he called one of the students in for "therapy," she did what she could. She'd spin stories and excuses, telling Maskell that they were studying or otherwise occupied by something that they couldn't get away from. Jean Wehner also added that, one day, Cesnik took her aside, just to ask if the priests were hurting her. When Wehner could only nod in reply, Cesnik promised that she would take care of it (though Maskell did continue to abuse students after that, too).

Even after Cesnik left her job at Keough and took a position at Western, she still gave the girls a safe space to talk. They were always invited to come to her apartment, where she checked in on the situation regarding Maskell. One of the students was actually there to talk about Maskell the night before Cesnik disappeared, only for Maskell himself to barge into the apartment. The student let herself out right away but could tell that Maskell knew what was happening.

Joseph Maskell threatened the girls not to talk

Joseph Maskell knew that the victims of his abuse would want to talk (and that they were talking to Catherine Cesnik, at least), so he had to shut that down — with violent threats.

There are a lot of different stories about how Maskell threatened the girls into silence, and Huffpost has the details. A girl who did threaten to report him soon found his gun in her mouth, as he told her that no one would believe her — he had a fancy degree from Johns Hopkins, after all. Another time, he pressed his gun to the side of Jean Wehner's head, actually pulling the trigger... only for her to realize it was unloaded. It came with the threat that he would tell her father that she'd been "whoring around," and that those consequences would be far worse. And that wasn't the only time he threatened to expose his victims, saying he would get one of the girls expelled and sent to a facility for having done drugs — a secret she'd confided in him because she'd thought he loved her.

The most terrifying though? One night, he invited Wehner into his car, only to take her to see Cesnik's dead body, long before it was discovered. With that came the ominous warning — "You see what happens when you say bad things about people?" The words scared Wehner into silence for decades.

There are theories surrounding Catherine Cesnik's murder

Given that Catherine Cesnik actively fought against Joseph Maskell's abuse by standing up for the girls, as well as Maskell's propensity toward really terrible threats, it's easiest to assume that the motive for her murder laid somewhere in that area.

According to People, Jean Wehner suspected that Cesnik had planned to go to police, finally exposing Maskell for what he was. In that case, Cesnik might've been killed to stop her from actually being able to do that. It's just a theory — one that makes sense, but also one that the police actually can't prove.

But it's not the only theory. Inside Baltimore sheds some light on the idea that Cesnik's murder wasn't a lone incident. There were actually six different murders that might all be connected with each other — three teenage girls, a teenage boy, Cesnik, and Joyce Malecki. All of them took place in the late 1960s and early 1970s generally around the Baltimore area, with many of the crime scenes and bodies sharing physical characteristics. But beyond that, all of them had ties of some kind to Maskell, either working with him or attending churches where he was a priest. Malecki's body was even found near Fort Meade, where Maskell was a military chaplain.

All six murders are still unsolved, so technically, the similarities could just be coincidence, but despite the lack of evidence, experience tells investigators that there's some connection.

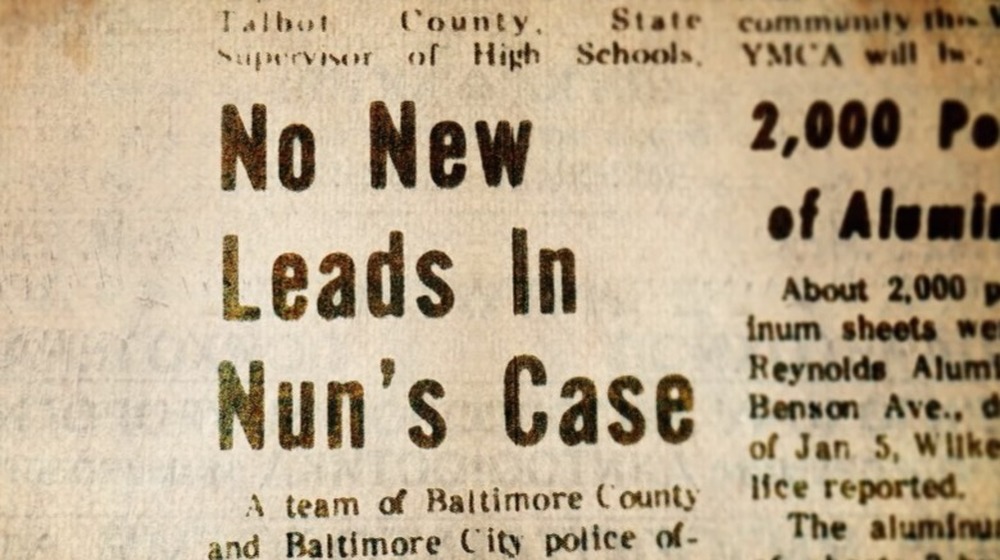

Catherine Cesnik's case still hasn't been solved

Despite the time, speculation, and later surge of interest in the case, Catherine Cesnik's murder has still gone unsolved.

The case made against Joseph Maskell in the 1990s didn't actually last. It was thrown out on a technicality, according to Huffpost. Without getting into a bunch of complicated legal jargon, victims of abuse would've had three years to come forward. Not two decades. Granted, there was the argument that this was, technically, still within three years — Jean Wehner and Teresa Lancaster had just recovered those memories. But that argument didn't fly in the 90s. There was a general backlash against it, and a Catholic psychiatrist argued that memories like that couldn't be repressed then recovered. So the case couldn't go forward.

Then there was a Baltimore gravedigger who told the police Maskell had ordered him to dig a hole in 1991 to bury files. Locating that stash, investigators found, among other things, nude pictures of underage girls. It was actual, hard evidence that would at least be enough to arrest Maskell for possessing child pornography. But, somehow, that evidence vanished, never making it to court.

Ultimately, Maskell died in 2001, having never been charged for a thing. CNN reported in 2017 that police had the okay to exhume his body for DNA testing, but even then, the DNA wasn't a match with what was found at the crime scene. Another dead end, apparently.

The investigation might have been hindered by the church (and maybe the police)

There might have been more going on here than just bad luck. Investigating a Catholic priest presented challenges, especially in Baltimore — a predominantly Catholic city (via Huffpost). Priests regularly got away scot-free.

The Catholic Church seems to know how to clean up its messes in general, with The Guardian uncovering a much wider scandal in Boston (which led to worldwide concerns). The Boston Archdiocese had been regularly making private settlements, paying for silence when it came to reports of abuse by priests. The scandals were always covered up by reassigning the offending priests to new parishes or just saying they were "on sick leave."

Rather conveniently, they also couldn't find any other corroborating statements regarding Joseph Maskell's abuse (Jean Wehner's lawyers had no trouble). But Maskell's case was complicated further by his ties to the police force through his work as a military chaplain. (Aside from reports that Maskell invited uniformed officers to assault the girls).

Maybe that was why a homicide detective was told to drop the case in the 1970s, blocked from investigating because higher-ups were "protecting someone." He ignored the order, only to be forced into an early retirement (via Inside Baltimore). The same happened in 1994. Another detective was looking into the case, only for a superior to tell him to stop. They already knew the murderer, but looking further would unearth information he wasn't supposed to know.