The World's Biggest Art Heist Is Still Unsolved, Here's Why

The biggest art heist in US history happened in 1990, and none of the paintings that disappeared into the Boston night have been recovered. That's shocking enough, and the story of the heist — and why it's gone unsolved — is downright wild. Let's start with some of the basics. It was just after midnight, and the fun of St. Patrick's Day was turning into the regret of March 18. When two police officers knocked on the door of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, the guards let them in. Needless to say, they weren't officers. The guards were tied up in the basement, while the two faux police officers headed out into the gallery.

The gallery, it's worth mentioning, was the life's work of a Boston socialite named — predictably — Isabella Stewart Gardner. She built the museum, says the Smithsonian, "for the education and enjoyment of the public forever," and it contained some of the country's most valuable pieces of art... but more on that in a minute.

The thieves grabbed 13 pieces in the next 81 minutes and walked back out of the gallery... never to be seen or heard from again. The museum is still offering a $10 million reward for any information that leads to the recovery of some or all of the paintings, and more than three decades later, they still call it a "top priority." Do some digging, and it turns out that the reasons the case remains unsolved are, well, wilder than imagination could come up with.

So, what was taken?

Let's start with the art itself, because the weirdness of the case starts here, too. The Isabella Stewart Gardner collection is made up of more than 7,500 pieces of art, 1,500 rare books, and another 7,000 of what they describe as "archival objects." But on March 18, 1990, thieves spent around an hour and a half walking the gallery to steal just 13 pieces.

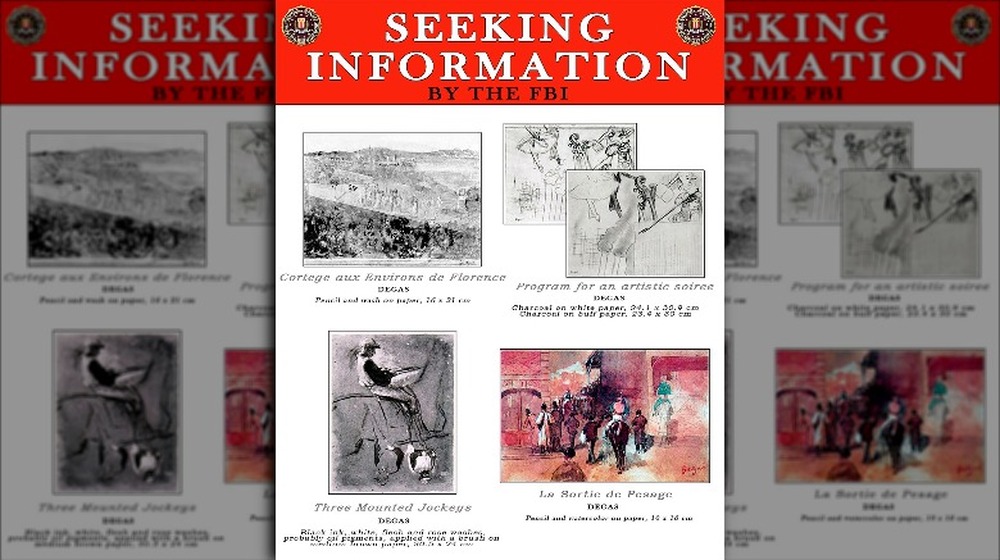

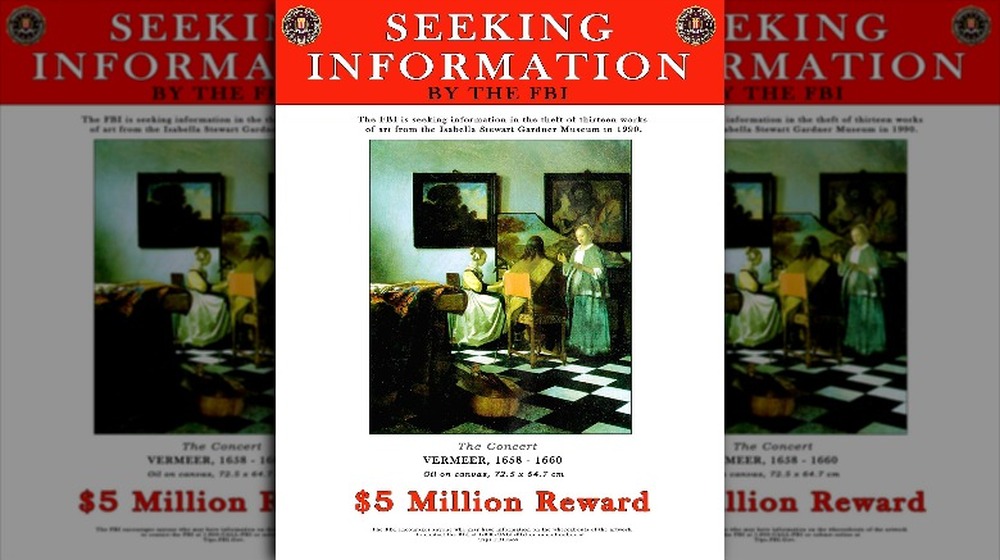

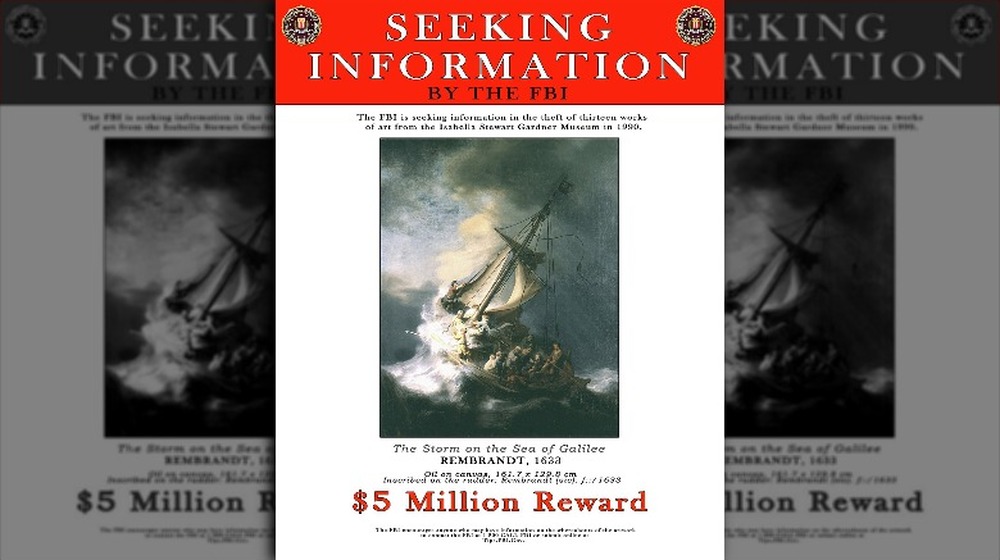

Among them, says WBUR, was Johannes Vermeer's "The Concert," (pictured, detail) which is one of the few confirmed Vermeer paintings in existence. (It's one of just 37 of his works.) Three Rembrandts were stolen (including his only seascape, "Christ In The Storm On The Sea Of Galilee"), along with one landscape by Govaert Flinck, a painting by Edouard Manet, and five pieces by Edgar Degas, along with a Napoleonic-era bronze eagle, and one of the oldest items in the collection, a Shang dynasty bronze beaker dating to between 1200 and 1100 BC.

Seems like a haphazard group of objects to steal, right? It absolutely was, and here's where the oddness of the case starts. According to Boston, the thieves clearly weren't concerned with preserving the art: frames were broken and smashed, canvases were cut from their mountings, and pieces were left behind... not exactly what an employer might expect from hired thieves.

What the thieves left makes literally no sense

In 1994, The New York Times reported that the 13 pieces of art stolen from Isabella Gardner's gallery were valued at a whopping $300 million, and sure, that sounds like a lot. But here's the thing: while they were definitely valuable, at the time there were 2,500 works on display. If the 13 stolen works were McDonald's burgers, the art thieves left behind some Wagyu beef.

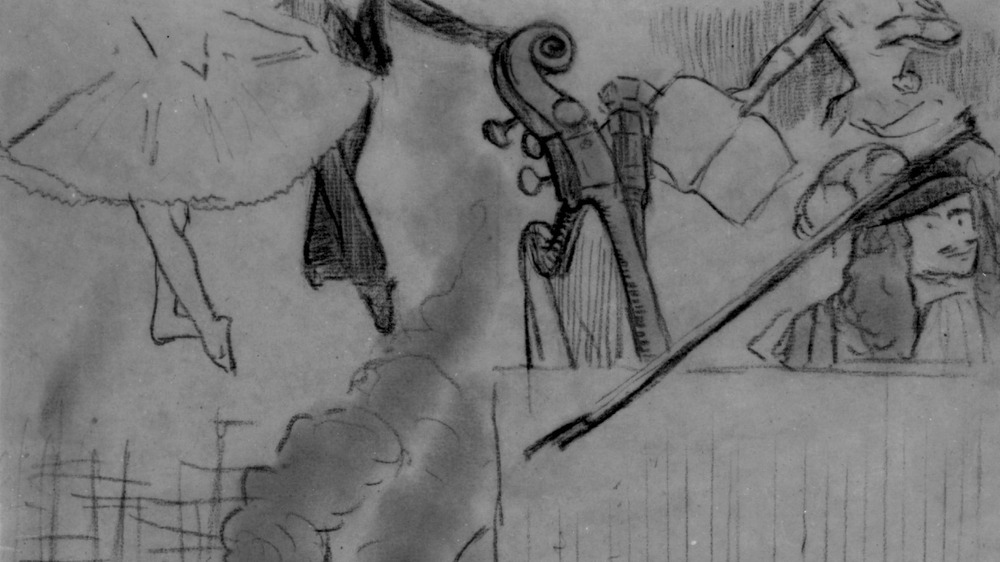

That included a painting called Rape of Europa by the Renaissance master Titian: not only does the painting have a place of honor in its own room, but it's been hailed as the most important Renaissance painting in a US collection since it was purchased in 1896: The museum says today, it's valued at around $25 million. It was the most valuable painting at the time of the robbery, too, and was untouched. During the thieves' 81-minute saunter through the gallery, they grabbed works seemingly haphazardly, even literally reaching past higher-value pieces. That included the Degas sketches: they passed up more valuable works for a handful of sketches (like the one pictured, which was among the stolen).

And that presented a problem right from the beginning of the investigation. Daniel J. Falzon was one of the FBI agents involved from the start, and explained, "We don't know the message. We don't understand the shopping list."

The theft wasn't discovered for five hours

The heist kicked off at 1:24 am on the morning of March 18 — that, says the Smithsonian, is when the two men dressed as police officers rang the bell and asked to be admitted. While letting them in was the first mistake, there was another that proved just as costly. Rick Abath was the guard who opened the door (while the second guard was making his rounds through the museum). He told WBUR that when the officers entered, they ordered him to step out from behind the security desk. He did — and when he did, he could no longer reach the museum's only panic button.

Because no one summoned the actual police, the robbery wasn't discovered until a shocking five hours later. That not only gave the thieves a huge head start, but also plenty of time to take tapes of surveillance footage with them.

The New York Times says that the guards were able to give a description of the two intruders, which included fake facial hair, their fake police department uniforms, and no obvious accents. Still, by the time actual law enforcement got there, the thieves — and the art — had been gone for hours.

There was zero chatter in the typical channels

Such an insane risk would only be taken if there was a good reason for it, logic says, and FBI spokesman William McMullin told The New York Times that was always part of the mystery, too. "What does a thief do with a Vermeer? You don't just roll it up and walk into a gallery and say, 'Can I have $30 million for this?'"

Stolen artwork is a huge industry in itself, and the FBI — along with other law enforcement agencies — has their finger on the pulse of the black market for stolen art. It's often used as a way to move money from one country to another, but the 13 pieces stolen from Isabella Gardner's museum (including the Rembrandt pictured) just sort of dropped off the face of the earth. As of 2015, there had not only been no ransom demands made, but reporter and art historian Tom Mashberg says that not a single piece — or even chatter about a piece — ever showed up anywhere on the black market. The art was simply gone.

There were just so, so, so many leads and possibilities

Part of the problem has been that there's literally hundreds and hundreds of leads, and little concrete in the way of evidence. There's no motive, fingerprints at the scene were nothing but a dead end, surveillance footage was gone, witness reports were spotty, and no word of the paintings ever surfaced. And all that left behind a ton of possibilities, with hundreds of people that needed investigating and hundreds of avenues that needed exploring... all of which took time, while the art slipped farther and farther underground, while fake leads got attention.

There's also those who believe it wasn't even about money. Museum director Anne Hawley was certain (says The New York Times) that there was something political about the theft. She points to the date — the night of St. Patrick's Day — in an overwhelmingly Irish city as a clue there's something else at work here. She suggested the perpetrators were "someone with a grudge against Yankee Boston," and that the theft was a message designed to be "in your face, with an intellectual twist." She also suggested that the roots of her theory go back a long, long time: "In olden times, 'If you capture the flag, you hold the field.'"

Is the symbolism of the stolen artworks more important than their monetary value? If so, it makes sense as to why they haven't surfaced — and why they may never show up.

A huge amount of time has been spent chasing theories

Law enforcement has spent a tin of time chasing down some insanely complicated leads, like the one that took them to Japan in 1992. According to The New York Times, it started when two Americans were invited to the home of a Japanese art collector. Hanging in his ballroom was a familiar painting: Rembrandt's "Christ In The Storm On The Sea Of Galilee" (pictured, detail). The FBI's Daniel Falzon headed out at the head of a search party. When he got there, he realized (via Vanity Fair) that he could immediately see it was fake, and their host was wondering why there was interest in a reproduction he'd had for the last four decades.

That's just one lead among hundreds, and when it comes to theories, there's enough to fill a wing of the Library of Alexandria. When word got out that the guard, Abath, had been seen buzzing someone into the museum the night before the robbery, the theory developed that it had been an inside job (via Oxygen). (Abath was only questioned about this in 2015, and said [via WBUR] he had no memory of the man or their conversation inside the museum that night.)

Other theories suggest the involvement of a well-known art thief named Myles Connor, connections to the Mafia, and the involvement of a screenwriter named Brian Michael McDevitt. From right at home to far abroad, there was a lot to investigate... and not a lot to go on.

The FBI missed a potentially important detail

The devil is in the details, the saying goes, and it's entirely possible that there was one tiny detail that could have opened up a new avenue to investigation... had law enforcement not missed it.

According to Boston, it was a later reexamination of the case by The Boston Globe that turned up an intriguing fact: one of the missing pieces of art, Rembrandt's "Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man," (pictured) had been stolen once before. Twenty years prior to the Gardner heist, someone had carried a bag of light bulbs into the museum, then smashed them. While the guards were distracted, they pocketed the postage-stamp sized piece and headed off. No one was ever apprehended and the piece was obviously returned, but under odd circumstances. An art dealer handed it over, claiming that someone had turned it in to him after they found it — several hundred miles away, in the New York City subway.

What really happened to the first thief, and how did it really turn up? Was there a connection? And was it a connection that would have led somewhere if it had been discovered sooner?

A 1994 tipster disappeared

The New York Times says that there were hundreds of tips, and that's a lot to sift through. It also means that the real tips can easily get lost, and it's possible that they did actually have a legit lead, way back in 1994. That, says Boston, was when law enforcement got a letter from an anonymous person, saying that they could arrange the return of the stolen artwork (including the Manet pictured). They wanted something in return, though: full immunity for everyone involved, and $2.6 million.

Law enforcement called the letter "the most promising lead ever," and followed the trail of breadcrumbs. After making contact by leaving a secret message — the number "1" printed in The Boston Sunday Globe on May 1, front of the exchange rate for US dollars to Italian lira — another letter showed up. There was a major catch that had developed — alarmed by the buzz through law enforcement about the letter, the tipster specified that the museum couldn't have arrests and the paintings, and he may — or may not — be in further contact.

They were never heard from again, and in 2015, director Anne Hawley issued another plea: "I call out to an important person. Years ago, I received a lead from a sincere individual... I very much hope this person will contact me again... I assure complete confidentiality."

The 1997 warehouse viewing that might... or might not... have happened

In 1997, William P. Youngworth III was facing charges of possessing controlled substances and firearms, and decided that a promise to arrange the return of 11 of the Gardner Museum's missing works might help him out a bit. Youngworth picked Boston Herald reporter Tom Mashberg to be the go-between, and as part of the deal, he arranged for a driver to take Mashberg to where he could show him one of the paintings.

Mashberg wrote (via Vanity Fair) that the painting he saw was "Christ In The Storm On The Sea Of Galilee." The edges were torn — as they should have been — and the signature looked legit. Mashberg wrote a version of the viewing for The New York Times years later, and he still wondered if he'd seen the real thing. At the time, he was 100 percent convinced — and negotiations for the art first began, then abruptly ended when no one on either side believed they could trust each other.

There's a footnote, here: Mashberg received some paint chips as proof that they really did have the art, and while tests indicated they weren't linked to the painting he saw, that kind of changed in 2003. The paint chips were examined again and this time, experts said they contained a pigment called "red lake." It had nothing to do with the Rembrandt, but it was a favorite of Vermeer's and had been used in the Vermeer that was stolen from the museum. Did the paintings slip through their fingers?

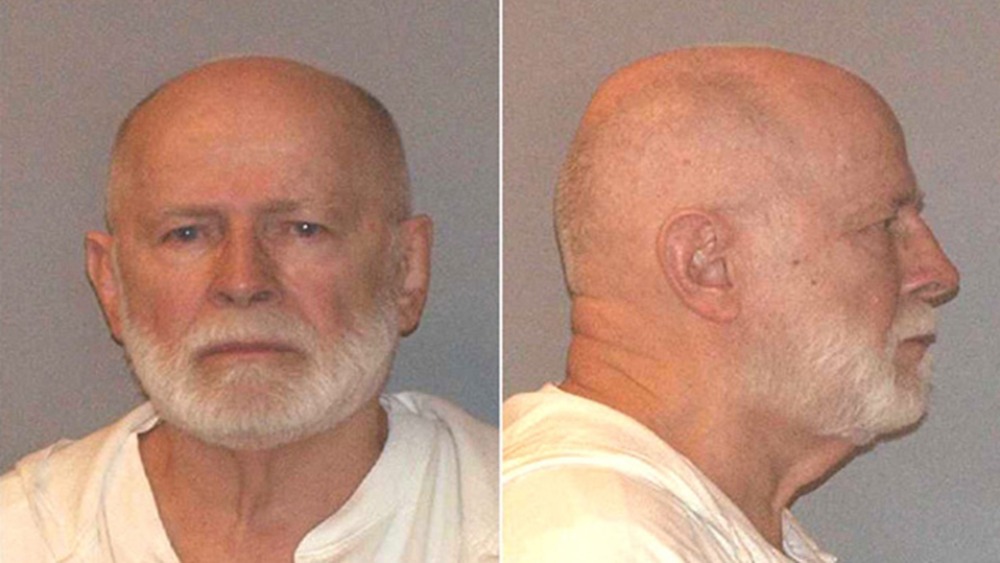

Whitey Bulger's possible involvement

So here's a theory: James "Whitey" Bulger — one of the most infamous mob bosses of the East Coast — either had something to do with the heist, or knew who did. According to WBUR, the FBI reached out to Bulger through a retired agent named John Connolly just a year after the theft. The two had a history — Bulger had been an informant in the 1970s and 80s, and Connolly had been his handler... who, incidentally, spilled the beans to Bulger about his imminent arrest, and allowed him to flee.

It only made sense that he would know — he ran Boston, after all. But here's the weird thing: when the FBI talked to Bulger, he said he wanted to get his hands on the thieves just as much as they did, as they hadn't asked for his permission first. The FBI still maintains that Bulger didn't know anything useful, and wasn't involved.

But according to The Guardian, it's possible someone's lying. At least one British detective — Charles Hill — believed Bulger had definitely been involved, and had the paintings sent to Ireland and into the hands of the IRA. Hill (who has headed up other art investigations and famously recovered Edvard Munch's "The Scream" in 1996) says the Gardner heist is exactly the sort of thing that Bulger — a well-known IRA sympathizer — would have capitalized on.

But Bulger's not talking: he was beaten to death in a West Virginia jail in 2018.

The theory that everything is hidden in a house across the ocean

Now, here's where the story about Bulger's involvement just keeps on going. In 2020, Charles Hill — now retired from the Metropolitan police department's art and antiques department — actually headed to Ireland to follow a tip he'd gotten on the whereabouts of the missing works from the Gardner collection.

His informant, says The Guardian, is Martin Foley. Anyone wondering what sort of person he is just needs to know that The Irish Times says he's also known as The Viper, so while there's no real proof that he's in the know, he's exactly the sort of person who would be, well, in-the-know. And he went on record as saying that he knows exactly where the 13 missing pieces of art are.

Foley claimed that the artwork was hidden in the walls of a perfectly ordinary house in a perfectly ordinary area of west Dublin. Foley, says The Art Newspaper, put the art (including the Degas sketch pictured) there himself around 30 years ago, when he was involved with the men who smuggled the artwork into the country. Negotiations fell through, and Foley has since made a few attempts at pointing law enforcement in what he says is the right direction. That includes a tip lodged with the Newcastle police department about 20 years prior, and while British police say it's very likely true, US law enforcement — and representatives from the Gardner museum — say that everything's still in the US.

The disappearance of a key informant

So, if everything about the artwork being sent to Ireland is true and there's an informant that's come forward saying they're willing to spill the beans... why is the case still unsolved?

Martin "the Viper" Foley disappeared, even before the BBC program about the art heist and his involvement was aired. According to the Irish Independent, the publicity around his partnership with law enforcement got the wrong kind of attention, and after being warned that there had been threats made against his life, Foley vanished. Foley — who had already survived four assassination attempts and 14 bullet wounds — was reportedly in the middle of working out a deal with the surviving gang members who were behind the heist originally, and detective Charles Hill.

According to The Guardian, Hill has been able to corroborate Foley's story with another anonymous — and criminal — source. The artwork is in Ireland, they say, and the entire thing was the work of a Dublin-based gangster named Martin Cahill. Perhaps most fascinatingly, they also give a reasoning behind the oddity of the thieves' choice in artwork. The Degas sketches (including the one pictured) all feature horses — which Hill says makes sense, if the person pulling the strings was a career criminal with an investment in the ponies and a love of the racetrack.

Still, with their best informant gone, the case remains unsolved.