How Much Money Did Witch-Hunters Make?

Witch-hunter: the once actual, honest-to-goodness 1500s-1700s profession with a name as fictional-sounding as "Martian-slayer" or "yeti-trapper." While societies across various cultures and historical epochs haven't exactly treated women with equality, dignity, and respect (Ancient Greece, Ancient Macedonia, Ancient Rome, the Ottoman Empire and more: we're looking at you), the savage, witch-hunting years following the publishing of the "Malleus Maleficarum" in 1486 definitely stand out for their utter ignorance and irrationally justified brutality. As soon as parishionerless priest Heinrich Kramer wrote his bestselling treatise about why the "inferior mental and spiritual capacities" of ladies (per Iowa State University) led them to consort with the devil, witchcraft "trials" took off. In the end, somewhere between 40,000 and 100,000 women were tortured and incinerated over the course of 200 years, per ThoughtCo. (The infamous Salem Witch Trials, for the record, came near the end of this craze, in 1692, per History.)

It isn't incorrect to assume, as Listverse points out, that frothing religious zealots were often to blame. Like villains seeking to legitimize their tearful backstories, clergymen Georg Scherer, Sebastian Michaelis, Balthasar von Dernbach, and Johann von Schonenberg, and more rampaged around the countryside torturing dancing women for church-sanctioned, Jerry Springeresque confessions like, "Yes, I slept with Satan and that's his child!" Other witch-hunters were failed lawyers, failed politicians, and other authority-loving, chip-on-their-shoulders failed-at-lifers. Some were merely mercenaries in it for the money.

If that's the case, and witch-hunting constituted a bona-fide, cash-generating profession, how much money was worth the suffering of thousands?

Commission-based pay in a time of blood for gold

Witch-hunting was a lucrative business deployed among the Europe population following a period of economic depression and poor crop-growing weather, per Aeon. Despite Pope Alexander IV outlawing witchcraft trials in 1258, less than 250 years before the release of "Malleus Maleficarum," his decision fell to the wayside once the Protestant Reformation took off in the early 1500s, starting with Martin Luther's "95 Theses," as National Geographic outlines. Both camps of Christianity needed recruitment boosts, and witch-burning was a powerful tool, not because it fostered greater fear of the Devil, but because of the death-spectacle that inspired religious awe and belief.

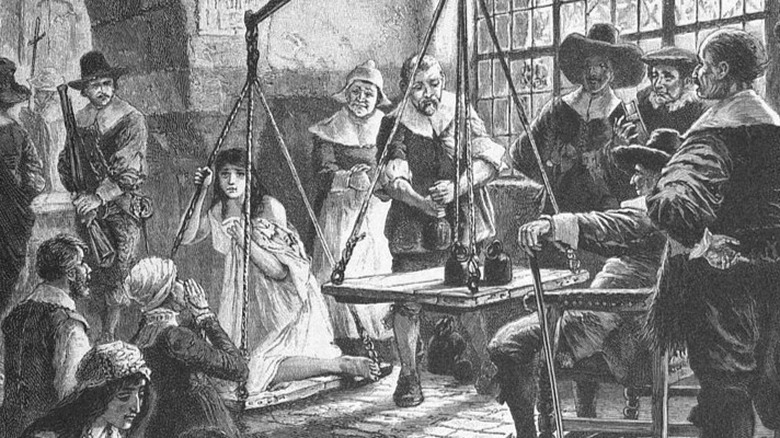

This is especially the case because it was the families of witches who bore the burden of the cost for trials. Attorneys, guards, court scribes, torturers, even shackles, handcuffs, and the very coal, peat, and tar used to execute a loved one: Families of victims received actual, itemized bills, as Lapham's Quarterly describes. In 1592, witch-hunt critic Father Cornelius Loos wrote, "[B]y cruel butchery innocent lives are taken; and, by a new alchemy, gold and silver are coined from human blood." Churches could galvanize their followers and their followers' tithes at the same time that they earned money from murder.

This meant that the utterly destitute weren't prime targets for alleged witchery. The moderately wealthy stood to lose their entire estates because of a trial, such as heiress Merga Bien, who as Listverse states, was executed while pregnant with "the Devil's child."

A month's wages or more for exposing a witch

As for witch-hunters' pay, there are scant resources available to state precisely how much money each witch-hunter earned. As King's College reminds us, each witch-hunt was different according to location, the target of the hunt, the witch-hunter on dispatch, and on whose dispatch he prowled. It stands to reason that, while the church wouldn't willingly part with its own blood money, it distributed enough to continue incentivizing witch hunters to maraud women who owned cats or had unluckily-placed moles.

The British Library recounts that a witch-hunter on the payroll could receive an entire month's wages for "exposing" a witch. Like salesmen on commission, they were incentivized to unearth as much ungodliness as possible. We can glean some further insight by focusing on one particular, historically notorious witch hunter, Matthew Hopkins. Hopkins, as the BBC explains, is responsible for the whole "if it floats, it must be a witch" test lampooned in "Monty Python and the Holy Grail." Toss a woman in water, he said. If she floated, the water rejected her because she wasn't baptized. If she drowned, she wasn't a witch.

Records show that Hopkins and his stooge John Stearne earned £23 pounds (over $5,600 in today's money) from hunting in Stowmarket, England. The average worker? Six silver pennies a day (about $1 today). 240 pennies, by the way, was £1, per the Royal Mint Museum. And Hopkin's total fees? Nearly £1,000 (about $245,000) over only a few years.