What Life Was Like For Women In Ancient Greece

There isn't a single answer for what life was like for women in Ancient Greece. Their reality depended hugely on which city-state they called home, during which period of Ancient Greek history they lived in, and how rich they were (or rather, how rich their husbands were.) But if you had to sum up what life was like for Ancient Greek women in one phrase, it would be "an absolute pile of poop."

After all, to Ancient Greek men, women were literally a curse unleashed by Pandora. An intellectual dinner conversation might be about how guys were similar to the gods, while women were basically animals. The ideal woman was no woman, but since they existed, they were supposed to model themselves on Penelope, the wife of Odysseus who waited faithfully for her husband for 20 years, just sitting in her house, spending her time sewing, and refusing male advances. In other words, boredom, servitude, and isolation was pretty normal back in the day, but it wasn't bad all the time, depending on where you lived and what you did for a living. From lady Olympics to religious rites, here's what life was like for women in Ancient Greece.

Rights? More like wrongs

Ancient Greece might be famous for inventing democracy, but the ladies there would probably have some thoughts about that. That illustrious institution overtly excluded them. Women outside of Sparta had virtually no rights. According to GreekBoston.com, they had to be accompanied every time they left the house, probably because men were afraid women would flee their oppressive lives the first chance they got. Women had arranged marriages to guys more than twice their age when they were young teens. And at every stage of their lives, they were completely under the control of their father or husband. If both those guys were dead, another male relative was in charge. After all, a woman couldn't govern herself. That would be crazy.

In most city-states, any education a woman did get was at home, because only boys went to school. But even then, ideally girls were educated "as little as possible." Remember how women might have some thoughts on the whole alleged democracy thing? If they did, it could only be in private, because not only were women refused participation in government, it was considered wrong for them to even talk about it in public.

Nor could they own property. Thomas R. Martin's Ancient Greece reports an heiress with a dead father and no brothers could find herself being legally forced to marry her late father's closest living male relative so she would have a son, and he would be the one to inherit.

Life was hard for a female slave in Ancient Greece

Life in Ancient Greece was hard on women. Many were treated like slaves ... and then, others quite literally were slaves. There was a simple way to tell them apart. If a free woman and her female slave were in the market, the free woman would be veiled lest her face give everyone cooties. The female slave would be naked. That's pretty much where the differences ended. Being a citizen woman (meaning the wife of a citizen, as women weren't citizens in their own right) wasn't all that different from being a female slave, which tells you how bad women's situations were.

But slave women did manage to have it worse, somehow. There was the backbreaking labor, beatings, nudity, and the whole being owned thing. According to Hellenica World, at best, working an important job in a rich home could bring higher status. Slaves were not allowed to marry because that was seen as a privilege. Since they were owned by their male masters, those masters could do whatever they wanted to them, including sexually. Slaves couldn't say no. But slaves were also not allowed to raise children. A pregnant slave was considered a problem, and a child was absolutely unacceptable, so at some point in the process it was disposed of, one way or another.

Female slaves had one good thing over male slaves. Since they were worth about 20 percent less, they were freed more often. FactsandDetails.com reports that over 60 percent of the inscriptions at Delphi freeing slaves are about women.

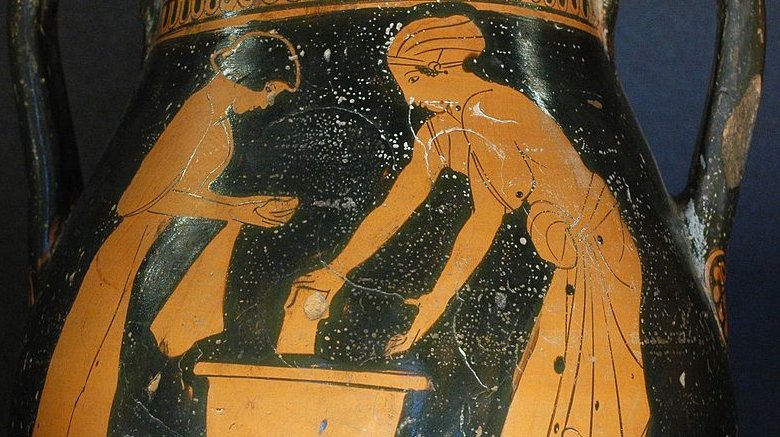

A Greek woman's place was in the home

Women were supposed to stay home. All the time. The Role of Women in the Art of Ancient Greece describes it as being "secluded" and "confined." This doesn't mean that women never left under any circumstances. They had permission to do so for certain festivals, and poorer women without slaves would have to go to the market themselves. If they did leave the house, they were probably veiled. But the ideal was that women stayed inside all the time. And for rich women especially, this was basically reality.

But they weren't just sitting on their butts. Even wealthy women with many slaves were expected to run the household, and that meant chores. Lots and lots of chores. It was like being a 1950s housewife but without vacuum cleaners or ovens or plumbing to make it even the tiniest bit easier. There was plenty of hands-on "weaving, spinning, sewing, grinding of grain, fetching water, washing, and bathing" to do every day. Women were also expected to serve meals. And those are described as the supportive tasks in the "easy life" of a rich woman, who would leave things like cooking and the manufacture of clothing up to the slaves. Of course, poor women would have to add those jobs to the list of stuff they had to do.

That doesn't even touch on the most important thing women in Ancient Greece would be doing in their homes: making babies. And we're talking lots of babies, specifically sons, and raising them with or without the help of slaves.

Dying to avoid womanhood

If a life of nothing but domestic servitude and pregnancy sounds terrible, young girls back then thought so, too. Womanhood would just show up one day. The Museum of Menstruation and Women's Health reports getting her period was considered the sign an Ancient Greek girl was a woman and ready to be married off to some guy, since she could finally have his babies. According to Rites of Passage in Ancient Greece: Literature, Religion, Society, the average Athenian girl married between 12-14. Men, on the other hand, regularly waited until they were in their 30s to marry. In other words, gross. Add to that the girls didn't choose their husband and like slaves they couldn't say no in the bedroom, and what you get is terrifying.

The fear of this disturbing situation was so great, girls around menstruation age committed suicide at an alarming rate, usually by strangling themselves with their own clothing. Even the ones who didn't often got so stressed out they suffered from a disease called the "illness of maidens." It included symptoms like "shivering and fever, hallucinations, homicidal and suicidal frenzies, pain, vomiting," paranoia, and a feeling of being suffocated. At the time, male doctors put it down to the cutting-edge medical science of "wandering womb," which meant their uterus was bouncing around their insides. The prescription was marriage and a quick pregnancy, which is just depressing.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The lady Olympics in Ancient Greece

Name something, literally anything, and Ancient Greek men probably banned women from doing it, watching it, or participating in it. Working? Nuh-uh. Politics? No way. Even just walking around the market? Totally frowned upon. This included the Olympic Games. Amazingly, it wasn't a complete ban. Young single girls could watch the naked men show off their sporting prowess. But if a married woman snuck a peek, she got thrown off a mountain. Still, the competing part was a men-only activity, so women started their own Olympics.

According to Atlas Obscura, the event was called the Heraean Games, and just like the boys' competition, it was every four years. It's not clear when or why they started, but they may be almost as old as the dude Olympics and seem to have been in honor of the goddess Hera. A total of 16 women from various city-states competed in footraces. Unlike the naked guys, they wore tunics, although they were cut very short and only covered half their chests. The winners received olive branch headdresses, plus part of a dead cow, and statues with their names carved on them were dedicated to them. Spartan women apparently won a lot of the time, as you'd expect.

Some historians don't believe the Heraean Games really existed, since there's very little evidence for them. Only a few ancient sources mention them, and none of the victors' statues have ever been found. But others say this is just a sign of the insignificance of women's sports to the Ancient Greeks.

Priestesses lived the good life

If you were a woman in Ancient Greece, there was one way to get equality: find religion. Goddesses needed priestesses, and priestesses were powerful. As Ancient History Encyclopedia puts it, "The priestesses of Greek religion enjoyed a great many perks that other Greek women did not." Placating goddesses was an important civic responsibility, so women who took the job got a paycheck, were often given property, and even commanded respect. They were seen as role models, and some became celebrities. Portrait of a Priestess: Women and Ritual in Ancient Greece (via The New York Times) records these religious women were honored with statues, had massive state funerals, and were even consulted on normally taboo political issues. They were, essentially, equal to men. Other common perks included no taxation, bodyguards, reserved front row seats at competitions, and legal benefits that women usually didn't have.

It got even better. Unlike the later Roman priestesses, no one in Ancient Greece expected their female religious leaders to stay abstinent. Priestesses could marry and have children, and some positions even required they be hitched. On the rare occasion a goddess cult insisted their priestess keep her legs closed, they usually selected much older women.

A priestess position could be inherited, purchased, or won by election. The job was a busy one. Of the 170 annual festival days in Athens, women participated in 85 percent of them. Even on non-festival days, jobs could include sacrificing animals, leading complicated prayers, and carrying holy items in processions. The most powerful priestess, the Oracle at Delphi, even told the future. Not a bad gig if you can get it.

A festival full of insults and naughty bread

Religion provided women a respite from the cruelties of men. According to Oxford Research Encyclopedias, women-only religious festivals that men were completely banned from were an important part of Ancient Greek life. If anything, at least it got women out of the house.

The biggest lady-only festival was Thesmophoria. Citizens (free Greek men) were required by law to pay any expenses so their wives could attend (single girls weren't included). Like a lot of religious rites involving women, it revolved around fertility and agriculture (aka plant fertility). The three-day festival took place yearly in the fall, and in Athens, there was even a dedicated spot for it right by the men's assembly, which women essentially took over. It was the closest they would get to politics. They even held elections for officials to preside over the feast.

There was a dark veil of secrecy over the festival, so it's not exactly clear what it involved. But what's known is seriously odd. It was like once the men were gone, the women let loose. ThoughtCo says a whole night was dedicated to "ritual insults" and swear words, where the women trash talked each other. They also made jokes about sex. You know, for religion. Then a select group of women retrieved a mixture of pig carcasses and bread shaped like male genitals that the women had thrown in a pit during the summer. A feast followed, full of more (fresh) naughty-looking bread.

Greek women (probably) liked a drink

While you can't assume Ancient Greek literature is true to life, any more than future historians should consider Paul Blart: Mall Cop an accurate representation of our society, there are things that can be gleaned from jokes and situations in the works of the time. Greek Prostitutes in the Ancient Mediterranean, 800 BCE–200 CE says no ancient texts directly talked about women's drinking habits, but playwrights sure did. And it seems to have been the stereotype in Athens that women were the drunks of society, not men. (Honestly, that isolated life of chores would drive anyone to drink.)

While the idea of women drinking is presented as "truly appalling," it's apparent that they did, a lot. Women in Greek plays were constantly talking about alcohol and how much they loved their local bar. In one play, a chorus asked the gods to punish anyone who harmed women, "worst of all" being bartenders who served short measures. Other works said women went to the bar as often as men went to court, and women were "overheated dipsomaniacs, never passing up a chance to wrangle a drink, a great boon to bartenders."

And despite the fact women weren't supposed to work, there's both literary and historic evidence that women were often bartenders and tavern owners themselves. In fact, because of the gendered nature of the word usually involved, it seems more women than men owned bars. In situations where their husbands owned the establishment, wives worked right alongside them, serving drinks.

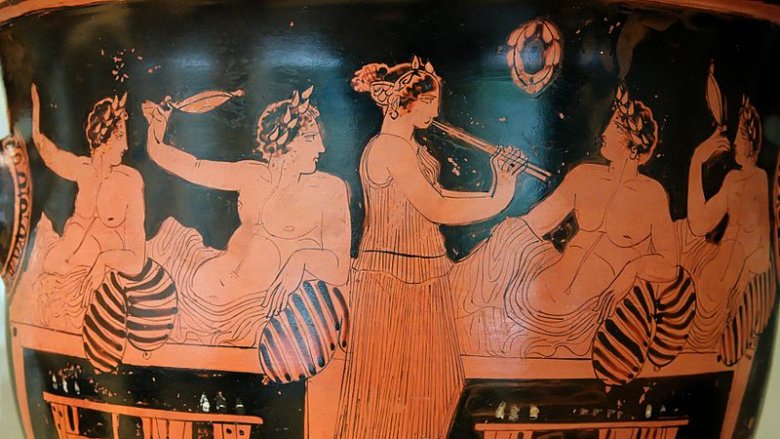

The oldest profession was a pretty good deal

While prostitution was rife throughout Ancient Greece, Athens became particularly famous for its brothels. Men, at least, considered it a vital part of society. According to Ancient History Encyclopedia, since guys waited until they were in their 30s to marry, they had to get their jollies from somewhere else before then. Seducing the daughter of a citizen would be unacceptable, so they had to turn to working women.

There were some upsides for the ladies employed to sell their bodies. The oldest profession paid well. Many of the women who ended up in prostitution were slaves, and they made more than enough money to buy their freedom, per The Vintage News. A single man would often move his favorite prostitute into his home, where she could live for many years as basically his common-law wife. But if being controlled by a guy didn't sound great, women in the profession were pretty much the only ones who could live independently and have financial security. And one class of working women called the "hetaerai" were well-educated and artistic escorts to the wealthiest men. They attended drinking parties and mixed with men in ways that wives didn't. It wasn't all good, though. The children of prostitutes were never considered citizens, no matter who their father was. This meant getting rid of said children was extremely common.

Wives were not supposed to complain when their husbands strayed. However, they did have access to their own fun, since men offered their services as well.

Ancient Greek women came into their own at funerals

Most women in Ancient Greece didn't get fancy funerals. But men did, and when a guy kicked the bucket, women came into their own. According to Slate, funerals were a chance for women to move beyond their traditional role of being an isolated maid and mother. Since most of the time their identity, thoughts, and personalities weren't considered important, "funerals were pretty much their only opportunity for public self-expression, so they made the most of them."

Other than actually burying the body, women were in charge of pretty much every part of Ancient Greek burials. This meant they were in charge of one of the most important parts of a person's, well, not-life, since the Metropolitan Museum of Art says that the Greeks considered a proper burial absolutely vital, and the omission of any of the various rites was "an insult to human dignity."

There were numerous stages of mourning. First, women washed the body and dressed it. While they did this, and pretty much at every stage of the funeral, they would be singing laments. There might be tearing of their hair and clothes. Three days after death, there was the funeral procession, which again was all about women and their lamenting. In one play, the women's laments got political, so funerals might have been an outlet for them. Then the body was buried. But the women's work wasn't done. They had to keep visiting the grave (pictured) and leaving cakes, because being remembered by the living equaled immortality.

The Spartan paradise

Life for women in most Ancient Greek city-states, particularly Athens, was so bad that it was "similar to the status of women under the Taliban today," according to Sparta Reconsidered. But there was one place they could have rights, a degree of freedom, and were even held in esteem.

Living in Sparta was the best it ever got for Ancient Greek women. Ancient History Encyclopedia says girls were given an education because the Spartan men were away fighting so often, and they knew the women they left behind needed to be able to run things. Female children got the same amount of food as boys, and they were encouraged to get lots of exercise (although the food and exercise was so they would give birth to strong boys who would be great fighters).

Spartan girls weren't forced into marriage right when they got their period. Instead, it was customary to wait until they were old enough to enjoy relations with their husbands. The rights didn't end in childhood, either. Women could own land, and they were allowed to fraternize with men in public, where they were able to hold their own in conversations. In fact, Spartan women were known for being outspoken and funny. Because women produced Sparta's warriors, ladies were "seen as the vehicle by which Sparta constantly advanced."

The rest of Ancient Greece thought their neighbor was nuts for treating women somewhat like humans. When Sparta fell into decline, it was blamed partly on all the freedom women had there.