Disturbing Details Found In George II's Autopsy Report

George II, the king of Great Britain from 1727 to 1760, was the last British ruler to appear in battle, according to Britannica. Alas, rather than die on the battlefield, he died an aged man of 76 when he reportedly had an aortic dissection in the process of trying to pass a bowel movement (per National Institutes of Health). Not the mode of death he'd probably wish for.

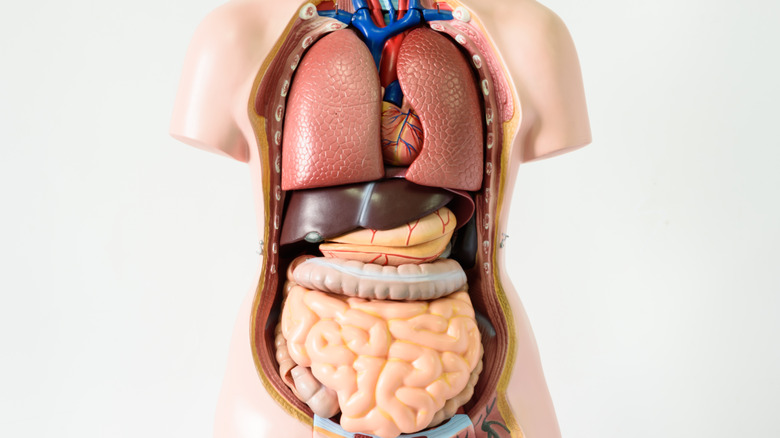

An aortic dissection is when the body's main artery, the aorta, tears its inner walls, potentially leading to a full split of the artery, according to Mayo Clinic. Its symptoms are similar to other cardiac crises and include chest pain (often accompanied by a ripping sensation), sudden stomach pain, a loss of consciousness, and symptoms that may appear to be neurological and resemble a stroke, such as trouble speaking. Aortic dissection, while relatively rare, is often fatal and requires open-heart surgery (though recently, there have been advances in noninvasive surgery for dissection repair, per Hektoen International). In King George's day, aortic dissection was hopeless.

There are other candidates for the cause of George's sudden death — in studying the king's autopsy, some have argued that the immediate cause was actually a right ventricular rupture caused by heart disease (via Thieme Medical Publishers). Here's what the autopsy said.

A pint of coagulated blood

According to the king's autopsy, on October 25th, the day of his death, George II woke up at 6 a.m., drank some hot chocolate, and went into his water closet in his home at Kensington Palace (via NIH). Soon, the king's attendant heard a noise from within the bathroom and ran in, finding the leader had collapsed on the floor, apparently dead.

The personal physician of the king, Frank Nicholls, performed the autopsy (which was important in order to ensure the king hadn't been murdered, per Thieme) and embalming. Nicholls began by dissecting the king's abdomen, then moved to his brain, and finally his chest. According to the autopsy report, he found that the pericardium (the membrane surrounding the heart) was "distended with a quantity of coagulated blood, nearly a pint" — a recognizable sign of aortic dissection.

According to NIH, this was the first recognizable record of aortic dissection by a medical expert. The picture painted in the report was a grisly one. "The whole heart was so compressed as to prevent any blood contained in the veins from being forced into the auricles; therefore the ventricles were found absolutely void of blood ..." Nicholls wrote. "And in the trunk of the aorta, we found a transverse fissure on its inner side, about an inch and a half long, through which some blood had recently passed under its external coat and formed an elevated ecchymosis."

The autopsy's conclusion was grim. The king had died "while straining on the toilet," according to the report.

Was coronary artery disease to blame?

The term "aortic dissection" was not used in the report, because it would not be coined until 1802, according to the NIH. Still, the king's death is widely known today as a famous example of the condition.

Some argue, however, that even though an aortic dissection did occur, it was not the primary cause of King George II's death (per Thieme). For one, though the report noted an inner tear on the aorta — a "transverse fissure" — the aorta did not rupture. The blood instead pooled under the outer layer of the aorta, and the right ventricle ruptured. This points to a sudden pulmonary event being the immediate cause of death, such as a large pulmonary embolism.

In his autopsy report, Nicholls wrote that the king had heart problems in his old age. "His Majesty had, for some years, complained of frequent distresses and sinkings about the region of the heart," the report said. "[His] pulse was, of late years, observed to fall very much upon bleeding." It's possible that the king may have had coronary artery disease.

The rest of the autopsy and the king's successor

The other findings in the autopsy were not notable. There were hydatid cysts around his kidneys, which, the autopsy notes, may have "eventually proved fatal," but they were still small and did not play a role in the king's death (via Google Books). His brain and lungs looked normal, according to Nicholl's notes.

George's son, Frederick, Prince of Wales, preceded his father in death. After George II died, succession instead passed to his grandson, George III, who infamously lost both the American colonies in the U.S. War of Independence and his own mind due to a mysterious mental illness (per Britannica).

Nicholls, for his part, did not attend to George III, according to the Royal College of Physicians. Instead, the physician moved with his family to Oxford and later retired in Epsom, where he died in 1778 at the age of 80.