What Happens During An Autopsy?

From reports about celebrity deaths, to true crime podcasts, to horror movies with titled things like "The Autopsy of Jane Doe," references to postmortems are everywhere. It's not surprising, considering nearly 7,000 people die every day in the United States alone, and autopsies are one of the most reliable ways to determine a cause of death. For loved ones of the deceased, the concept of an autopsy can be initially distressing, but as a 2001 survey showed, many family members felt reassured by the results. Having answers about what caused the death can provide clarity and help with the grieving process.

However, according to PBS, there is a massive shortage in forensic specialists qualified to perform autopsies. This vital job is complex, requires years of education and training, and the temperament to handle working closely with cadavers, some of which met with violent ends. This is what happens during an autopsy.

The following article contains descriptions that some readers may find disturbing.

Why is an autopsy performed?

The primary goal of any postmortem is to determine why a person has died. As seen in almost every detective show, autopsies often examine bodies found under suspicious circumstances. As detailed in Indiana's Autopsy Protocol, in cases of things like death by fire, homicide, or of pilots in airplane crashes, people in prison, or children, an autopsy is always performed. In many states, deciding if the situation the body was found in seems suspicious enough to merit an autopsy is the job of the coroner. If authorities don't think an autopsy is necessary but a family member disagrees, they may hire a private expert to investigate. As noted by PBS, in some extremely contentious cases, such as pop star Michael Jackson's death, the family may even insist on a second autopsy.

Even if the death wasn't a homicide, autopsies can still uncover crimes. Some autopsies reveal that the victim was killed by negligence. If their job took them to places that were hazardous or their medical care was inadequate their next of kin may be able to file a lawsuit. Forensic pathologists have also identified deaths caused by bioweapons like Anthrax in time to prevent future attacks.

Forensic pathologists have learned information from routine autopsies that have saved countless lives. As many as 40% of autopsies reveal medical conditions that were never diagnosed while the patient was alive. Since many conditions are hereditary, this can give surviving family members a chance to get treatment.

Who performs an autopsy?

Very few people are legally allowed to even be in the room during an autopsy. For each autopsy, there is a list of everyone who is allowed to be present during the procedure. The rules governing who actually performs the procedure are not as set in stone.

A 2011 report from NPR noted that experts want to move away from having coroners in charge of determining cause of death and deciding if an autopsy is necessary. The requirements vary from state to state, but many have elected officials as coroner and do not require a medical degree – or any college degree at all. Ritesh G. Menezes and Francis N. Monteiro's "Forensic Autopsy," explains that autopsies should ideally only be performed by doctors who specialize in forensics. As explained by the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, all forensic pathologists are medical doctors. Their total education takes at least 10 years. PBS reported that in 2009, there were fewer than 500 full-time forensic pathologists worldwide. While they are encouraged not to complete more than 350 autopsies in a year, approximately 500,000 autopsies are ordered every year.

They can be assisted by forensic mortuary technicians or anatomical pathology technologists. The requirements for this essential role vary by region. In New York City, these techs are expected to have experience working on autopsies and in a mortuary, but do not need a college degree. In the U.K. there is a two-year training program.

Where is the autopsy performed?

While horror movies sometimes depict an autopsy being done in a cold, echoey room with flickering lights, the reality is a lot more sterile. As described by "Forensic Autopsy" they are typically performed in rooms near the mortuary. They are brightly lit, well ventilated, and specifically built for these procedures. Typically, the techs and forensic pathologists are wearing medical scrubs. In emergency circumstances, however, emergency autopsies have been performed in more unusual ways.

Autopsies sometimes have to be conducted where a corpse is discovered, because the decomposition is so extreme that moving it to a morgue would damage it. This may also be necessary when a body is exhumed in the course of an investigation. Mass-disasters like hurricanes and earthquakes can also necessitate autopsies outside of a morgue.

The disaster manual "Management of Dead Bodies in Disaster Situations" advocates that disaster preparedness should include preparation for autopsies. This requires facilities that will have running water, be well-lit, and has tables of the appropriate size. Ideally, these should be stocked with instruments like scales, hammers, and scalpels. While not every person who dies during a natural disaster is autopsied, it can be highly useful to understand how and when victims were killed. It can also assist in identifying the bodies. In emergencies like these where it is not possible to bring a body to a morgue to be inspected by forensic experts, emergency autopsies have been performed by ordinary doctors with nothing but a kitchen knife.

What tools are used?

"What we have is a combination of surgery implements and common garden tools and kitchen appliances," pathologist Jeffrey Nine (via The Atlantic) explained. In many ways, autopsies are very similar to surgeries, and many of the same tools are used – with a few notable exceptions.

When stocking a facility with supplies to perform an autopsy, "Management of Dead Bodies in Disaster Situations" recommends many tools that are used in procedures with living patients, like scalpels and forceps. Similar to a biopsy in many standard procedures, samples from the body are taken to be analyzed in labs later. For this, they use well-labeled sterile containers, sometimes filled with formaldehyde. Other standard tools for postmortems, like hammers and electric saws, may be less familiar but may also be used on a living patient. Others like "skull chisels" are tools specially designed for autopsies. Nine explained that rather than use a bone saw for ribs, he uses garden shears intended for cutting hedges.

The ability to bring gardening tools into the procedure isn't the only difference. While surgical tools need intense sterilization in order to be safe for use, a morgue's implements only need a regular sanitary rinse (like is used on restaurant food prep areas or baby bottles) because there is no possibility of harming the cadaver.

Step 1: Preparation

Forensic pathologists are a major part of many investigations. As explained by Britannica, they are sometimes called to inspect the crime scene and observe the body where it was found. They may be able to determine an approximate time of death at the scene. Once the body has been moved to the morgue (a vital task performed by death scene investigators) the forensic pathologist can begin an autopsy.

The entire postmortem is carefully documented, but it typically begins with detailed notes about the deceased. This includes where the body was found, and if known, what they were doing when they died.

As explained in "Autopsy Protocol," the forensic pathologist needs to be fully briefed about the investigation of the person's death, if there is one. They may communicate with police detectives and review evidence. If there were any weapons found at the crime scene, the forensic pathologist will inspect them, and report back if the victim's wounds match.

Step 2: External examination

Before they look inside the corpse, the forensic pathologist examines everything about the outside. As explained by Indiana's Autopsy Protocol, this includes evidence from the scene, the victim's clothing, and finally, the body itself. The state of decay is noted, a dental exam is performed, and skin is inspected for any injuries and wounds, big or small.

Pathologists record descriptions of all wounds and traumas on the body. In some cases, they are able to determine a likely cause of death from these external injuries – such as asphyxia or gunshot. Not all injuries are so standard in appearance, however.

In one bizarre case, published in 2020's volume of "Forensic Science International: Reports," a woman's body was found in the wounds with peculiar stab wounds. During the postmortem, it was noted that, "there were multiple rounded and triangular doubled tears to the clothing" and the stab wounds on the body were strange, irregular shapes. Weeks later, the police located a novelty "fantasy knife," intended for display only. The strange wounds matched up perfectly with the unusual blade.

Step 3: Identification

Sometimes when a corpse is discovered it isn't clear who they were. In fact, it is often estimated that there are around 40,000 unidentified bodies in the United States at any given time. An autopsy can help identify the dead.

As explained in the victim identification procedures listed in "Autopsy Procedures," this includes photographing any unique clothing or jewelry and potentially identifying marks on the body, such as tattoos. Postmortem radiology uses portable X-ray machines to locate "foreign objects" like bullets, but they can also be used to bone fractures both old and new, which could help to figure out who the person was. X-rays are also sometimes used to find fragments of bone in places where a body may have been destroyed.

Some of the most effective methods of identifying a body are dental exams and DNA. ABC News reported on the case of an unidentified skeleton that had been found in 1987. In 2019, her identity was discovered. In 2005, DNA from the skeleton was added to California's missing person's database. Over a decade later when the DNA matched with that of a family member of a murdered woman, an examination of the teeth was used to confirm the skeleton's identity.

Step 4: Incision

Probably the mental image most people have of an autopsy: that Y shaped cut down the chest. It is created with three slices. The first two start at the shoulder, stretching to meet each other on the chest. Then a third is made from that same point, vertical down the chest.

One might expect gore, but there is almost none. Between the 1100s and the 1800s, the justice system used something called "cruentation" to attempt to solve murders. Like modern forensics, it involved cutting into the dead body, but it had no basis in science. As explained by National Geographic, if the victim's body was cut with a knife while the murderer was present the wound would gush blood. In reality, postmortem cuts barely bleed at all because the heart is no longer beating. A process called livor mortis causes the body's blood to collect on the side it has been resting. Within six hours it will no longer move.

That famous Y cut isn't the only way to begin a postmortem, as explained in Ritesh G. Menezes and Francis N. Monteiro's "Forensic Autopsy." In fact, the most common is actually I shaped. It is a straight cut that goes from the chin to the groin.

Step 5: Organ removal

Once the body is opened, it is time for the pathologist to inspect the organs. The "Handbook of Autopsy Practice" by Jurgen Ludwig (via "Forensic Autopsy") lists four different techniques for removing and inspecting the organs. The first involves carefully removing each organ from the corpse one at a time. The second involves dissecting the organs while they are still inside the body. The third "en bloc" method calls for removing the organs in groups, rather than separating and removing one at a time. The "en masse" removal technique refers to taking all of the organs out at once.

Whatever method is used, each organ (and its contents) must be documented and individually weighed. The Royal College of Pathologists explains that the weights of certain organs may point to diseases. The kidneys, lungs, heart, bladder, and many more can be inspected to determine if particular drugs or toxins were ingested.

A case report describes a highly rare finding – the stomach was full of a strange blue substance, and the inner GI tract was stained bluish as well. They conducted an experiment, placing one of the capsules that held the deceased's pain medication into a jar of saline. After half an hour, the jar containing the capsule turned the strange blue that had been discovered in the autopsy. They were able to conclude that they had died of an overdose of the medication.

Step 6: Samples

One of the main purposes of an autopsy is to take samples of tissues, organs, and fluids in the body for later testing. As stated by Johns Hopkins, while the autopsy itself takes somewhere between two and five hours, analysis of the samples can take weeks.

The Royal College of Pathologists explains that toxicology testing can sometimes find a cause of death even when it wasn't discovered during the autopsy. Blood, urine, gel from the eyes, and stomach contents can all reveal poisoning, whether accidental or intentional.

CBS News reported on a man's murder in March of 2021 that was cracked using forensic toxicology. The death was initially considered a heart attack, but the victim's family requested an autopsy anyway. While the autopsy itself found nothing suspicious, the tests done on the blood sample did: a chemical called tetrahydrozoline, a dangerous substance commonly found in eye drops. The victim had been poisoned.

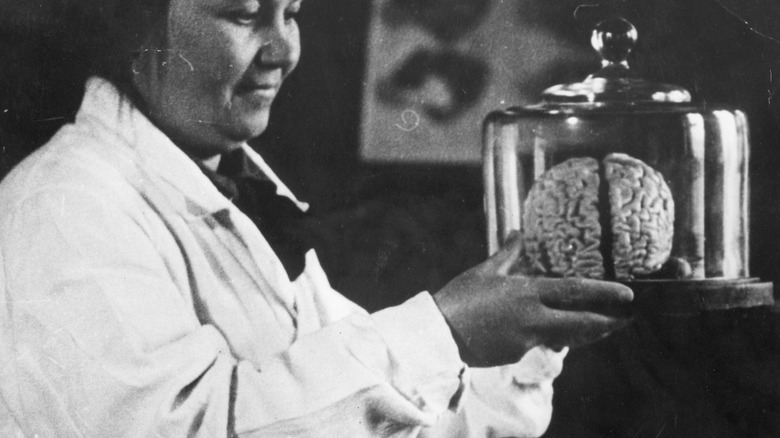

Step 7: Brain

"The thing about the brain," Dr Suzy Lishman stated during her lecture via The Royal College of Pathologists, "It's really hard to get to."

Despite how difficult accessing the human brain is, it is vital that it be inspected during an autopsy. First an incision is made with a scalpel behind one ear. The cut goes around the back of the skull, ending behind the other ear, allowing the scalp to be pulled away from the back of the skull. This placement at the back of the head is a discreet one. After the autopsy is complete, everything can be put back into place neatly enough that it is nearly undetectable, in case loved ones are planning a viewing.

Once the scalp is pulled back, the technician or pathologist will use a saw (either oscillating or manual) to cut through the skull. To remove the top of the skull, a chisel – sometimes called a "skull key") and mallet are used. The brain is inspected for signs of damage or injury. Nerves are cut, and the delicate brain is carefully eased out of the skull. A neuropathology department may inspect the brain whole, or it may be sliced and inspected during the autopsy.

Step 8: Reconstruction

After the autopsy, the body is put back together as neatly as possible.

As explained in Dr Lishman's lecture, the organs are placed into a biodegradable bag and then put back into the cadaver. The skull is put back together and the scalp sewn up. During an interview with the Atlantic, medical student Ellen Sun expressed regret that the reconstruction couldn't be "perfect," due to the breaking of bones necessary during an autopsy. Between the careful work of the autopsy team and a funeral home, however, it is possible for the victim's loved ones to have a viewing, and even an open casket funeral.

Sometimes pathologists take certain measures in advance that will make a funeral home's job of making the corpse look presentable easier. As stipulated by the College of American Pathologists "Guidelines for Cooperation Between Pathologists and Funeral Professionals In Matters Pertaining to Autopsies," these can include the use of a different initial incision if there is a concern that a Y cut might show under the person's burial clothing, padding being used to ensure that the face is protected at all times throughout the procedure, and alerting the funeral home to any possible cuts and marks that they may need to cover.