Was Niccolo Machiavelli Really So Machiavellian?

Nowadays, the term "Machiavellian" denotes all manner of conniving, manipulative, spurious, and twisted machinations. If someone plays games with others on a personal, professional, even political level, resorting to subterfuge, coercion, inveiglement, and so forth, rather than dealing with things in an up-front, forthright away — it's totally "Machiavellian."

Perfectly pristine ethics ought to be the norm across the board, such a person might say, chin held high, faultless, and heroic. Realists in the crowd, though, might turn their heads in response, saying, "You can't be so naïve about things. That's not how the real world works." If you fall in the latter category, then congratulations: you've reached Machiavelli's own conclusions.

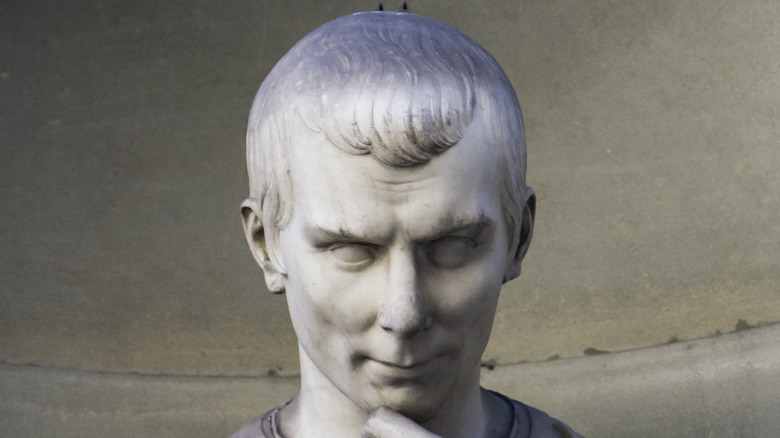

Niccolò Machiavelli, the man, is one of those historical figures who's been influential enough to have an adjective coined after him, like "sadistic" (Marquis de Sade), "chauvinistic," (Nicholas Chauvin), "quixotic" ("Don Quixote," written by Miguel de Cervantes), "Dickensian" (Charles Dickens), and many others. Machiavelli was a Florentine during the Italian Renaissance, born to a wealthy family in 1469 on the cusp of a tumultuous historical period known as the "Italian Wars," which lasted from 1494 to 1559 altogether (via Britannica).

This era of ludicrously complex conflicts between various nobles, Italian states, the pope, foreign powers, and more, formed the backdrop of Machiavelli's outlook and work as a politician and writer. When the democratic government of Florence finally crumbled into the autocratic fist of the Medici family, as History outlines, Machiavelli was tortured, exiled, and wrote his chief work, "The Prince."

Turmoil and manipulation on the Italian peninsula

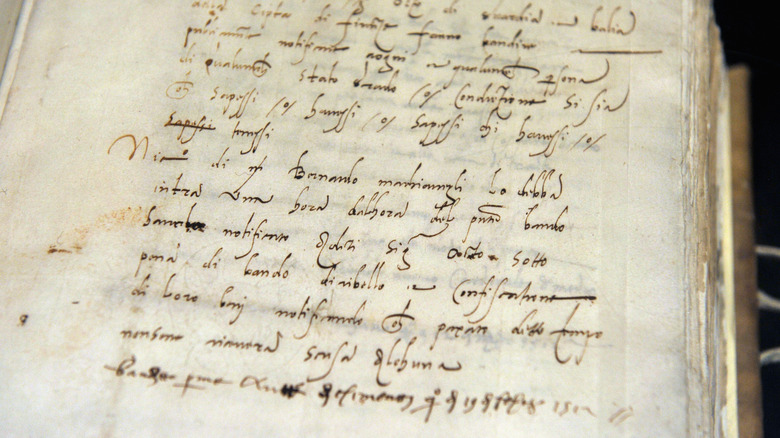

Machiavelli, by all accounts, intended "The Prince" — written as a long-form letter — to be political advice for Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici, then de facto leader of Florence from 1513 to 1519 (via Britannica). This happened after the Medici family returned to Florence after having been exiled from 1494 to 1512 for raising the ire of the public when Piero de' Medici, Lorenzo's father, sided with the French in a political conflict (via Britannica). And, the Medici were only able to return because another Medici, Giovanni (Lorenzo's uncle), became Pope Leo X in 1512 (via Italy on This Day). Like we said, it was a convoluted time of manipulation and cut-throat politics.

When Lorenzo got back to Florence, the Medici cleaned political house by booting Machiavelli out of the city for not having supported them. Machiavelli, in turn, wrote "The Prince" to regain his old status and position within the city. Some, though, have suggested that "The Prince," far from being earnest advice for Lorenzo, was actually a scathing satire of the man and other such tyrants (as an article in The American Scholar on JSTOR relates).

There's no telling whether or not Lorenzo even read "The Prince." Regardless, Machiavelli's work stands as a testament to the realities of political life, far beneath broad, surface-level ideologies and slogans. It resonates all the way to the present, whether in giant organizations like the UN, or your local school board.

A grim, but realistic view of human nature

"The Prince" reflects the brutal political tactics of the time in which it was written, as well as the impact such tactics had on Machiavelli's own life. At first glance, and without the proper context described above, "The Prince" can come across as an exhortation for amoral manipulation. Rather, it just assumes the worst in people.

A longer sample from "The Prince" on ThoughtCo reads, "For this can be said of men in general: that they are ungrateful, fickle, hypocrites and dissemblers, avoiders of dangers, greedy for gain, and while you benefit them, they are entirely yours, offering you their blood, their goods, their life, their children ... when need is far away, but when you actually become needy, they turn away."

Another quote reads, "There are two methods of fighting, the one by law, the other by force: the first method is that of men, the second of beasts; but as the first method is often insufficient, one must have recourse to the second. It is therefore necessary to know well how to use both the beast and the man."

Was he wrong? Anybody who's been alive for more than five minutes might reply, "Of course not." But that doesn't mean that other, nobler, selfless facets of humanity aren't also true, just that focusing on either to the exclusion of the other is foolish. In general, these are the kinds of debates inspired by "The Prince."

Spain obliterated Machiavelli's militia

Machiavelli's perspective took a hard turn towards cynical on the heels of being put in charge of a governmental project that he himself had pitched: building a citizen army, i.e., a militia, to retake Pisa. Florence was a huge manufacturing center but needed access to a port because it was located inland. It eyed nearby Pisa for generations because of the town's location along the Italian western coast, and eventually, Pisa fell under Florentine control in 1409 (via About Pisa). It took all the way to 1495 for Pisa to re-assert its independence, as Military History recounts.

To get Pisa back, Machiavelli pitched his militia idea to the Grand Council of Florence, which was then still a republic and not under authoritarian Medici rule. In 1506, by a vote of 817 to 317, he received leave to build a militia. Machiavelli personally traveled around the Tuscan countryside recruiting a peasant army of 5,000. At that point, he wasn't completely disillusioned by humanity and believed that Florentine patriotism would be enough to ensure victory. Machiavelli didn't want to assault Pisan citizens, though. He wanted to lay siege to the city and instructed his soldiers to have food ready when they surrendered, to welcome them back into the Florentine fold.

By 1509, he'd been successful in reclaiming Pisa (via Britannica). Three years later, though, Florentine political bungling led to their city being assaulted by Spain. Machiavelli's militia was massacred, and the Spaniards butchered another 5,000 citizens inside Florence.

Machiavelli was tortured and exiled

The failure of Machiavelli's militia to defend Florence from Spain, especially following the recent success of his campaign against Pisa, left a permanent mark on him. This is precisely when the Medici family came back to Florence under the protective hand of the newly-appointed Pope Leo X (Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici). From 1512 to 1513 the Medici regained power in Florence, the city's republic was put on the path to complete failure and abolishment, and Machiavelli saw not only Florentine democracy, but his entire life's work, dashed to pieces. This is when he was tortured as a political dissenter and exiled, as History explains.

It was that same year, 1513, that Machiavelli wrote "The Prince," as Military History relates. His fury was running high, soured by a dejected, spiteful malaise and newly kindled hatred of pretty much anything and everything. To be sure, this sentiment comes across in "The Prince," no matter how restrained, taut, and rational the writing is. Perhaps thinking of himself as the vengeful injured man in the following passage, he wrote, "If an injury has to be done to a man it should be so severe that his vengeance need not be feared" (via Goodreads). Significantly, he also wrote, "How we live is so different from how we ought to live that he who studies what ought to be done rather than what is done will learn the way to his downfall rather than to his preservation."

A prolific writer in his later years

"The Prince" remained widely unread during Machiavelli's life, as History says. It was published in book form posthumously in 1532, and over the coming centuries came not only to typify the politics of Machiavelli's day but a specific brand of "realpolitik:" a political outlook that espouses a practical, not head-in-the-clouds, set of principles towards statecraft.

Even though "The Prince" didn't make an impact until after Machiavelli's death, plenty of his other work did. During his long exile, from 1513 to his brief re-entry into political life in 1526, he spent most of his time at his villa, writing. "The Discourses on the First Decade of Titus Livius," as ThoughtCo explains, were intended to be a set of instructions for future generations regarding how to hold down a stable, representative government. As is the case with "The Prince," Machiavelli looked to historical data and the lives of specific individuals to construct his ideas, as was the case with a retrospective on mercenary leader Castruccio Castracani. Machiavelli also wrote a couple of comedies, "Mandragola" (1518) and "The Clizia" (1525), as well as some plays, poetry, and a single short story, "A Fable."

When Machiavelli restarted his political life in 1526, it was at the behest of the Medici to review the stability of the city's walls, via Military History. One year later in 1527, the Medici were, once again, briefly overthrown. Machiavelli, as though tethered to the Medici by fate, died one month later.