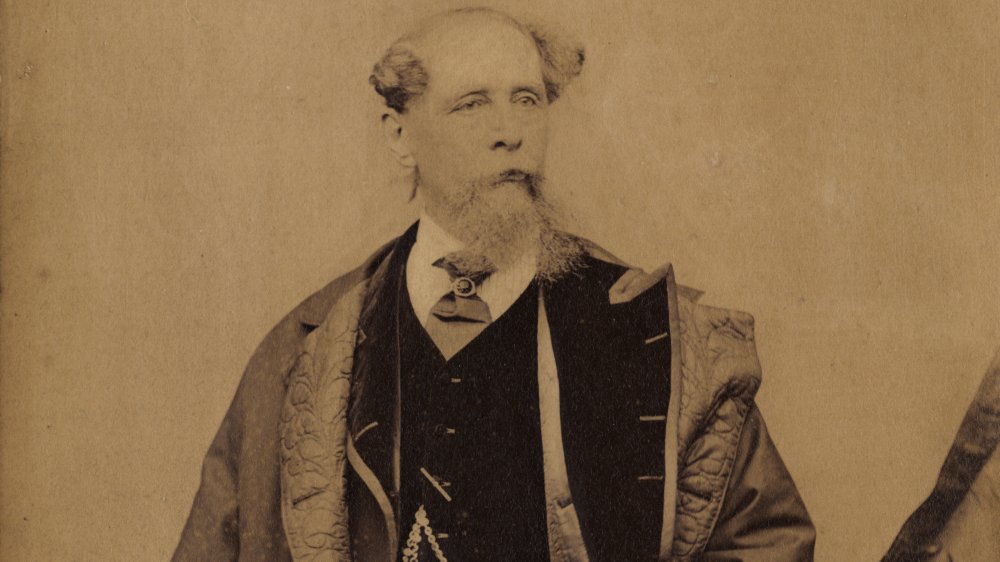

The Troubled Story Of Charles Dickens

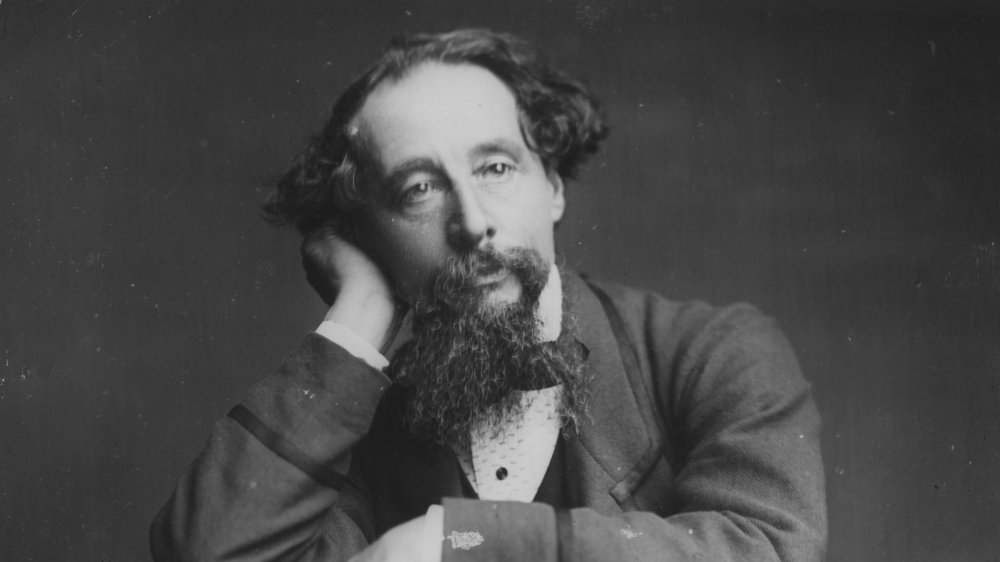

Charles Dickens was one of the greatest writers the English language has ever seen. His work remains a vital part of popular culture, and he's one of a handful of writers that even people who don't like to read are familiar with. After all, if you've ever watched one of the dozens of adaptations of A Christmas Carol in theaters or on television, you know Dickens.

Living and working during England's Victorian Era, Dickens' work is marked by its length and verbosity as well as its exploration of our common, universal living experience. Dickens explored poverty and debt, the shocking state of education and the orphanage system in England at the time, and unrequited love. Set against a lushly detailed portrait of the world and often spanning entire lifetimes of his characters, novels like Great Expectations, David Copperfield, and A Tale of Two Cities have become iconic works of literature.

Many people don't know the troubled story of Charles Dickens behind the writing, however. Much of the misery depicted in Dickens' work was drawn from his own life, and he wasn't always the nicest guy in the world. None of that takes away from the greatness of his literary achievements — but it definitely changes the way you interpret and enjoy his work.

Debt stole Charles Dickens' childhood

Anyone even casually familiar with Dickens' work knows that certain themes crop up over and over again. Although modern adaptations often play up the whimsical Victorian setting of his stories, themes concerning debt, poverty, and rough, unhappy childhoods are everywhere. The source of these themes, sadly, was Dickens' own childhood.

As Forbes notes, Dickens' father, John Dickens, was a man who struggled his whole life to make a living and provide for his family. As this was long before there were child labor laws, when Charles was 12, he and his older sister Fanny were forced to leave school, and he had to take a job at Warren's Blacking Factory. The little boy sat in a room with dozens of other children pasting labels on bottles of shoe polish.

As The Guardian reports, this experience was a horrible one for Dickens. Far from the sort of "summer job" modern-day teenagers get, his workdays often lasted as long as ten hours. He later said of the work that "no words can express the secret agony of my soul" and described the "grief and humiliation" he felt. There's little doubt that this awful period in Dickens' childhood influenced his writing, as debt and the way childhood can be turned into a bleak, desperate experience are frequent themes explored in his fiction.

Charles Dickens lost his little brother and sister

The Dickens family was a large one: Charles was the second oldest and had six siblings. Sadly, two of those siblings died very young.

As author Keith Hooper writes, Alfred Allen Dickens was born in March 1814. Since the Dickens family was enjoying a rare moment of financial stability, John Dickens chose to announce the birth in a London newspaper. Charles was just two years old, but he never got the chance to get to know his brother. Alfred died just six months after he was born. According to author Michael Slater, the official cause of death listed at the time was "water on the brain," which likely indicates a form of hydrocephalus.

Dickens' sister, Harriet, was born when Charles was seven years old, and he had a much stronger relationship with her. As Keith Hooper notes, not much is known about Harriet or how she died. It's theorized that she died of smallpox and that her death came close on the heels of Dickens' beloved Aunt Fanny's passing, giving the young boy a double dose of grief at a very young age. As Michael Slater notes, Dickens then lost his older sister Fanny, in a sense, when she went off to boarding school, leaving the young boy bereft and alone.

Charles Dickens' father went to debtors' prison

It seems amazing in the modern age, but in the not-so-distant past, people were actually routinely jailed for not paying their debts — as in literally put in prison. This often set up a cycle, since people in prison have trouble earning money, thus frequently making these into life sentences. In the United Kingdom during the 18th and 19th centuries, in fact, about 10,000 people went to prison every year due to unpaid debts. And one of those people was John Dickens, Charles' father.

As The Genealogist reports, prison records reveal that on February 20, 1824, John Dickens was sent to Marshalsea Debtors' Prison over a debt he had to a local baker. Charles was just 12 years old at the time, and Forbes reports that he was forced to leave school and get a job in a blacking (shoe polish) factory as a result. In fact, Charles' mother and four of his siblings actually moved into prison with their father, having no place else to live!

The BBC notes that the only reason John was able to escape the cycle of debt was through an inheritance he received when his mother died. Charles' mother argued that he should keep working at the blacking factory even though his father was a free man again, but Charles was able to return to school shortly afterward.

Charles Dickens' family was evicted

Charles Dickens' father, John, was perpetually in debt and even served a term in Marshalsea Debtors' Prison in 1824, which forced Charles to get a humiliating job at the age of 12 and forced his mother and siblings to move into the prison with their father for a time because they couldn't afford to live anywhere else. John was eventually saved from his time in debtors' prison by the inheritance he received when his mother passed away.

With his father out of debt, Charles was able to go back to school, and according to London Remembers, his family was able to move into a small house at 29 Johnson Street in London. But as author Micheal Slater writes, the Dickens family's financial troubles weren't over. In 1827, they were evicted from this humble home for unpaid rent, forcing them to live in temporary lodgings in the Polygon, a large multifamily building in a declining area. Dickens later included the Polygon in his novel Bleak House, where he described it as "in a state of dilapidation quite equal to our expectation [...] dirty footprints on the steps were the only signs of its being inhabited."

At least John Dickens avoided going back to debtors' prison over this new financial disaster.

Charles Dickens' first love was lost

As author Robert Garnett writes, when Charles Dickens was just 18 years old, he met a woman named Maria Beadnell and fell helplessly in love. Beadnell was two years older than Dickens. As The Guardian reports, he spent the next three years of his life pursuing her. He also wrote a large volume of poetry about her, representing some of his earliest literary work and standing as evidence of his strong feelings for her — as is the fact that she is believed to be the inspiration for two characters in his novels: Dora Spenlow in David Copperfield and Flora Finching in Little Dorrit.

Dickens was initially considered an acceptable suitor for Maria, although her mother apparently continuously got his name wrong. But after more than a year of pursuit, the family changed their mind about Dickens. As Robert Garnett notes, they began putting obstacles in his way — insisting, for example, that all their dates be chaperoned. The Beadnells became worried about Dickens because of his father, whose ongoing financial straits and stint in debtors' prison made him not exactly the sort of in-law they wanted. They packed Maria off to school in Paris, where she quickly lost interest.

Many years later, Dickens and Beadnell began a fresh correspondence, and Dickens expressed excitement at the prospect of reigniting the love affair — until they actually met. Dickens was so disappointed in Maria's middle-aged looks, The Guardian notes, that he wrote of her, "We have all had our Floras, mine is living and extremely fat."

Charles Dickens tried to have his wife committed

For many, Charles Dickens is a genial writer who loved Christmas and orphans. But as writer and historian Tony Williams points out, Dickens was a man who controlled his public image very carefully. He worked hard to keep many aspects of his life private and promoted a carefully cultivated persona to the world so successfully that it persists to this day.

When Dickens separated from his wife, Catherine, in the 1850s, it was initially believed that she had suffered a nervous breakdown stemming from the death of their young daughter Dora. Dickens took pains to promote this idea in public. As historian Lillian Nayder points out, Dickens wrote a letter to a newspaper claiming that Catherine had become a danger to her own children to the extent that her sisters had to take over caring for them. Dickens orchestrated a campaign to discredit Catherine's mental health to justify his decision to leave her and kick her out of his house.

As Nayder makes clear, Dickens did all this because he'd fallen in love with a younger woman and wanted to pursue the relationship — but he was mindful of his image as a family man and a morally upright public figure. So he needed an excuse to send his wife of 20 years packing. But as Smithsonian Magazine notes, he wasn't content just to drive her away — he actually tried to have her committed to an insane asylum. Luckily for Catherine, he failed.

Charles Dickens' daughter died

Charles and his wife Catherine had a lot of kids — ten in all by the time Dickens was just 40 years old. Only eight of those children survived to adulthood. As The Daily Beast notes, Dickens followed a distinct pattern with his children. When they were very young, he was affectionate and often doting, giving them whimsical nicknames and plenty of attention. As they aged into adolescence, he began to grow distant.

With his youngest daughter, Dora Annie, he never got the chance. Born in 1850, Dora was frail and sickly from birth. Her mother, Catherine, was sent into the country shortly afterward, possibly suffering from postpartum depression. For his part, Charles was obviously very fond of his new daughter. As author Robert Gottlieb writes, Charles spent much of his time playing with the children, "carrying little Dora about the house and garden."

Sadly, little Dora didn't survive to her first birthday. As author John Forster writes, while Dickens was out giving a speech, the little girl suffered "convulsions" and died. Dickens was stricken by the loss. His eldest daughter, Mary, wrote in 1889, "I remember what a change seemed to have come over my dear father's face when we saw him again ... how pale and sad it looked!"

Charles Dickens had an affair

The story of Charles Dickens and his wife, Catherine, is a sad one. By all accounts, they were initially happy, but Dickens began to drift from his wife in the 1850s. As Biography notes, in 1857, the 45-year-old Dickens met 18-year-old actress Ellen "Nelly" Ternan (pictured above) and fell in love. He embarked on an affair with her that lasted the rest of his life, and as author Lillian Nayder explians, he launched a cruel campaign to make the world believe his wife was crazy so that he could pursue Ellen.

Dickens was clearly restless and looking for new companionship. Before meeting Ternan, he'd reconnected with his first love, Maria Beadnell, and even met with her — but he was disappointed in her appearance, calling her "extremely fat." When he met Nelly, he launched a campaign of gaslighting and behaving monstrously toward his wife. As Yahoo News reports, he actually had a wall built between their rooms to separate himself from Catherine, and Smithsonian Magazine reports that after forcing her to leave the house and accusing her of being mentally unstable and dangerous to their kids, he tried to have her committed.

All of this was so he could be with Nelly without scandal. As a public figure, Dickens couldn't be known as a philanderer. He paid for Nelly to live in a nearby town where he could visit her secretly.

Charles Dickens' son died in India

Charles Dickens had ten children with his wife Catherine. His fourth, son Walter, showed some interest in following in his father's footsteps and becoming a writer. According to Culture Trip, however, Dickens supposedly discouraged this, even going so far as to secretly instruct Walter's tutor to advise against it.

When Walter was just 16 years old, he expressed a desire to become a soldier, which Dickens encouraged. He helped Walter enlist in the East India Company, which, at the time, was a private military force operating in India which later transitioned to being part of the official British Army. Walter attained the rank of lieutenant while living in the city of Kolkata (then known as Calcutta), living there for six years in apparent contentment.

However, Walter fell into debt. His disastrous finances plagued him, and his mental and emotional state began to decline. Things got so bad that the army was preparing to ship him home as an invalid when he suddenly died of an aneurysm in 1863 at the age of just 22. He was buried in Kolkata, where his body remains today, and Charles didn't hear of his son's death for some weeks. DickensLit.com notes a sad epilogue: Shortly after learning of Walter's death, Dickens received a delivery of his son's unpaid bills.

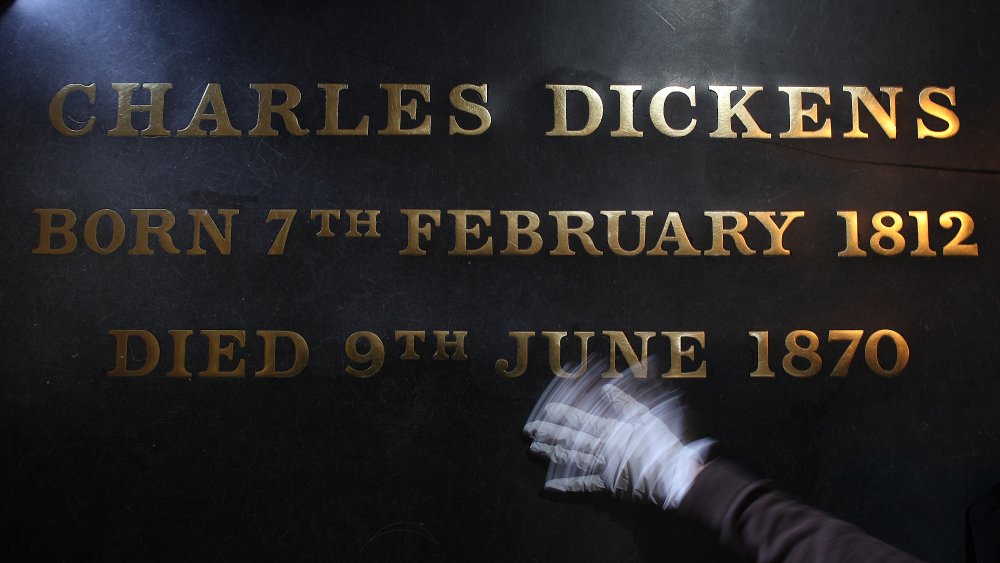

Charles Dickens died young

Charles Dickens was a hard-working man. Pursued by the ghosts of an impoverished childhood that saw his life disrupted frequently by his father's debts, the terror of poverty is a common theme in his books. This terror drove Dickens to work almost constantly. Although Dickens died of a stroke, as author Harold Bloom writes, "it's hard not to think it was fundamentally exhaustion" that really caused his death.

As Biography notes, Dickens was only 58 when he died. But Dickens' physical decline began earlier. He was involved in a horrific train accident in 1865, suffering injuries that never totally left him. And as medical journal Hektoen International notes, he suffered an earlier, more mild stroke in 1869, and his doctor tried to force him to slow down and stop working so hard. But Dickens refused to listen and continued a punishing schedule of public appearances.

He also kept writing and was working on his final, unfinished novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, when he took ill in June 1870. As The Guardian notes, he was initially in denial about his illness, calling it a "toothache" and insisting that he would feel better after a little rest — right before collapsing and falling unconscious. He never recovered, and he died the next day.

Charles Dickens resented his kids

Charlies Dickens had ten children with his wife Catherine, eight of whom survived to adulthood. You might assume that such a large family indicated a family man who wanted as many children as possible, but you would be very wrong.

As The Observer notes, Dickens was initially a doting and enthusiastic father. He lavished attention on his children, giving them whimsical nicknames and playing with them. But as they grew older, he began to sour on his kids. As The Daily Beast notes, he grew distant as they aged and often worked to settle his children in careers or other situations far from home when they were still teenagers. Worse, as Bright Side notes, Dickens became resentful of his large family and blamed his wife's "fertility" for her near-constant state of pregnancy. A man who had grown up in a financially unstable household, he worried about supporting so many kids.

As his children grew up, Dickens was openly disappointed in them. He said of his children that he'd "brought up the largest family ever known with the smallest disposition to do anything for themselves." There was a clear pattern of lessening affection as his children grew up — when his son Walter expressed interest in becoming a writer like his father, Dickens took steps to actively discourage him and then arranged to ship him off to serve in the army in India.

Charles Dickens' last wishes were ignored

Charles Dickens was a man who carefully monitored and controlled his public image. He was also one who worked hard to keep his private life just that — private. Even when it came to his own death, Dickens had some very specific ideas about how his funeral and burial should be handled.

As Smithsonian Magazine reports, Dickens left very specific instructions in his will about how his earthly remains should be handled. He describes a simple funeral, without publicity or ostentation and even specifies precisely where he wanted to be buried: a small graveyard near his country home. The sites that fit that description were found to be closed to new burials, however. Instead of trying to find a way to honor Dickens' wishes in spirit, his family first thought to inter him at Rochester Cathedral, a much grander place than Dickens had envisioned.

But even that plan was eventually put aside in favor of the exact opposite of Dickens' desires. As one of the leading literary figures of the time, a campaign began to have Dickens buried in the Poets' Corner at Westminster Abbey. To say that this was about as far from a modest graveyard near his beloved home as possible is an understatement, but that is where the writer's body went, and where it remains today.