What Solitary Confinement Really Does To Your Body

Solitary confinement isn't just about having some alone time to think about your life and the decisions you've made. People living in isolation in U.S. penitentiaries live more like research samples in petri dishes— overwhelmingly bereft of meaningful interactions, exercise, and the light of day. The United States is one of the only remaining countries to use long-term solitary confinement on its inmates, which has been deemed a human rights violation by the government itself, according to civil rights lawyer Laura Rovner. Most prisoners "in the box" or "in the hole" — as these concrete closets are commonly called — are usually there for one to three months, but many spend more than a year in segregation, per Scientific American.

The late U.S. Senator John McCain said that during his two years in solitary confinement as a POW in Vietnam (per BBC), "The onset of despair is immediate, and it is a formidable foe." Per the United Nations, Nelson Mendela shared a similar sentiment, saying that isolation is "the most forbidding aspect of prison life. There was no end and no beginning; there's only one's own mind, which can begin to play tricks." In solitary confinement, the mind and body unravel more quickly than one might think as it tries to survive an environment that is the complete antithesis of how we form and maintain our identity.

Skin and Weight Problems

When it comes to a convict's complexion in segregation, one of the first culprits to blame is the lack of sunlight they get to soak in. Inmates in isolation only get to go outside for one hour a day, and most of the cramped cells where they reside the majority of the time don't come with windows, according to a study published in the National Library of Medicine. Prisoners like Doug Wakefield, author of "A Thousand Days in Solitary," said he lost his hair in combination with developing perpetually flaky skin and permanent darkening around his eyes. Prisoners in isolation also unsurprisingly don't have access to the best hygiene products, leading them to develop annoying itchy conditions like dermatitis, which then result in more skin problems due to scratching.

Weight loss is usually one of the first symptoms of solitary confinement, according to New York University. Prisoners seem to follow a pattern of having both appetite and digestion problems during the first three months in solitary confinement. There are a variety of reasons why inmates shed a good amount of poundage in their concrete closets, including a loss of appetite, hunger strikes as a form of retaliation, anxiety and emotional distress, the paranoia of being poisoned, or just hating the food. One detainee, Jonathan Lancaster (now deceased), was reported to have lost 26 percent of his body weight, or 51 pounds, in three weeks during a psychologically traumatic stint in solitary confinement (via Rolling Stone).

Musculoskeletal Pain Everywhere, All the time

Musculoskeletal pain is pain that is essentially anywhere in your body, from the inside of your bones to the ligaments, muscles, and nerves on top of them. This type of pain is often associated with a prolonged lack of movement. To that end, being stuck in a dark space barely big enough to fit a king-sized bed makes it hard to get those steps in. According to a study published in the National Library of Medicine, prisoners talked about how their pain is anywhere and everywhere all of the time. One participant in the study described his musculoskeletal pain as, "I'll start thinking like oh, I'm laying in bed too much. Maybe my muscles are starting to rot, you know, eating on themselves."

It turns out you don't even have to be a convict in solitary confinement to feel musculoskeletal pain, either, as it's tied to being lonely, according to studies published in the PLoS One and Annals of Behavioral Science. Research also shows that the more time people spend disconnected from others, the more prevalent their physical pain seems to be. And the more time people spend with their pain up in their face (not literally — well, maybe), the risk of developing suicidal ideation increases. So, if your back's been bothering you AND it's been a hot minute since you've seen your friends or family, you might want to give them a call immediately.

Onset of Cardiovascular Complications

It's no secret among neuroscientists, psychologists, and inmates themselves that solitary confinement is one of the most stressful situations we can find ourselves in. And we all know how much our heart just loves stress! Studies have shown that prisoners in solitary confinement experience hypertension three times more than their counterparts in the general population. Researchers have also found that nearly 48% of incarcerated males between 27 to 45 years old in solitary confinement have high blood pressure, per Public Health Post. According to a study published by the PLoS One, one isolated inmate in the Washington State Department of Correction said, "I've been told I have a heart murmur ... I've been feeling my heart, like, feeling weird like it flutters once in a while ... [I] just don't tell nobody ... because they won't do nothing about it unless you're actually having a heart attack ... and then charge you 4 bucks."

Even people who aren't in solitary confinement can have cardiovascular problems if they experience a good amount of loneliness, which tells us that social isolation, in general, weighs heavy on the heart. According to studies in the BMJ Journals, loneliness is linked to a higher risk of heart attack, stroke, and increased mortality. Mind that some of these medical complications can result from underlying conditions that exist already, but loneliness seems to exacerbate these risks. So in case the healthy introverts out there are feeling more pressure to get out more, you're probably okay.

Total Sensory Deprivation

If not already apparent, there aren't many activities available in solitary confinement that create a significant amount of stimulation. Light and sound are also incredibly limited "in the box," so there also isn't much to distract yourself with for 23 hours a day. Eyesight deterioration becomes fairly common for stow away inmates as they never get to use their long-distance vision, according to civil rights lawyer Laura Rovner, who represents prisoners of Denver's ADX supermax prison. Survivor Robert King, a detainee who spent 29 years in a Louisiana prison alone, was nearly blind when he was released from prison, per Smithsonian Magazine.

Another inmate from a psychopathological study published in The American Journal of Psychiatry said that they became very sensitive to noise. "The plumbing system," they said. "Someone in the tier above me pushes the button on the faucet, the water rushes through the pipes— it's too loud, gets on your nerves. I can't stand it — I start to holler. Are they doing it on purpose?" Sensory deprivation is also known to worsen the psychological state of prisoners, who say that they often feel confused and unable to hang on to their memory, according to the Social Welfare Action Alliance. Some pretty in-depth and ethically questionable research by the CIA around psychological torture has also shown that isolating the senses can make it much easier to manipulate someone who is severely under-stimulated. Wonder what the CIA was studying mind control for ...

Involuntary Trembling

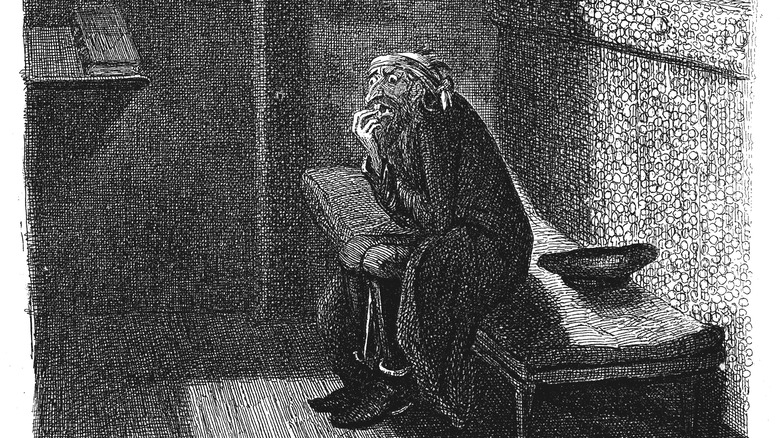

While it might seem cliche, involuntary movements like rocking back and forth or shaking are actually another actual ailment that can happen to the body during solitary confinement. Social isolation can completely zap the nervous system, and it was something acclaimed author Charles Dickens observed when he toured the United States in 1942. Dickens wrote in his journals of the visit about various physical and psychological deteriorations he saw: "They would pick at the fingers, unable to make eye contact, keep a conversation going, cringing posture and nervousness that led them to burst into tears."

According to a study published by the National Library of Medicine, there is a neurological connection between social bonding and our susceptibility to later stressors. This was evident to American psychologist Harry Harlow, who conducted multiple experiments on monkeys by putting them in solitary confinement in the 1960s. The young primates in the studies would compulsively rock back and forth and huddle in the corner of the cage in fear once they were reintroduced back into social situations with other monkeys (via Frontline PBS). His research suggests that severe social segregation at a young age can permanently damage our ability to foster curiosity and connections, per the Association for Psychological Science.

Decreased Brain Complexity

"If you are shut up with only your own thoughts, you suffer from mental starvation," wrote solitary confinement prisoner Delawrence Billingsley from the Chippewa Correctional Facility in Michigan, courtesy of Silenced. Decreased brain complexity from solitary confinement has a pretty strong link to sensory deprivation. A study about eight expeditioners in Antarctica in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that monotonous environments and social isolation restrict us from generating new neurons for learning and memory. The research showed that even hanging around with the same people in the same place every day showed an overall shrinking in the participants' hippocampus — a vulnerable and malleable part of the noggin that is responsible for learning, memory, and emotional regulation.

Translate that over to people in solitary confinement who get 9x6 cells and one hour a day of social interaction outside, and it's safe to say their cognitive function suffers astronomically worse than a bunch of vagabonds at the South Pole. When the hippocampus is shrinking, it accelerates the death of brain cells, particularly when people are depressed, per a study in Biological Psychiatry. Robert King, a prisoner who spent 29 years in solitary confinement, had lasting impairments when he was released back to civilian life, including an inability to navigate and recognize faces, per Scientific American. It doesn't take that long for the bean to start shriveling, either, as a research study using mice at the University of Philadelphia showed that it only took one month for motor regions in the brain to shrink by 20 percent, per Scientific American.

Paranoia sets in

Inmate letters from Silenced often suggest that their paranoia in solitary confinement is usually linked to alleged abuse from prison guards. Some talk about guards planting weapons or stolen objects in their cells as a way to send them to the box. Others recount the guards making them endure long periods without sleep by banging on their doors every 15 minutes throughout the night or conducting aggressive cell searches on a regular basis.

Per Rolling Stone, the sister of Jonathan Lancaster, a late inmate from solitary confinement, observed that he was becoming severely paranoid. "He was saying there was gas pumped into his cell. That his food was being poisoned ... Then he whispered ... 'They're going to kill me.'"

Doug Wakefield was 32 years old when he began writing his book, "A Thousand Days of Solitary," during a life sentence at Long Lartin Prison in Worcestershire. His self-documented symptoms of 1,200 days in solitary covered the full swath of ailments on this list, including a deepening paranoia of the people and the world around him. He wouldn't leave his cell if things became too unbearable, even to exercise, "because of the fear that they, the prison guards, will be leering at me each step I take ... I feel convinced that people are being 'planted' around me as spies in order to dig out and unearth all my deepest and innermost thoughts."

Uncontrollable Delirium

Delirium is a psychiatric illness that tends to be pretty rare, aside from susceptible people who have had long, long stints in solitary confinement. It's known to arise from environments that don't come with a lot of simulation (an evident pattern here) and with the onset of sensory deprivation, according to a study published in the Washington University Journal of Law and Policy. During Charles Dickens' visits to Philadelphia prisons in the mid-19th century, he watched inmates have conversations with themselves, stare at their hands and pick at their flesh, and look around at the walls in confusion rather than respond to him when he talked to them.

While it's weird to say it, that's not too bad in comparison to what others observe today, like inmates cutting themselves without being aware that they're doing it or smothering themselves and their cells in feces. Anthony Graves, a former inmate on California's death row, said (via American Psychological Association), "I would watch guys come to prison totally sane, and in three years they don't live in the real world anymore ... [one guy] would go out into the recreation yard, get naked, lie down and urinate all over himself. He would take his feces and smear it all over his face."

Intolerance for Stimulation

It's not uncommon for inmates to spend months to decades in solitary confinement, which can ironically lead to permanent intolerance for social situations thereafter, according to PBS. "I mean, there are still times where I may go to the walk-in, and after the movie's over and, you know, it's like I've been in the dark, and all of the sudden the light comes on, and boom, all these millions of people around me, I'm like, you know, looking around like, okay, okay, who's gonna hit me, what's gonna happen," a former prisoner recounted from his years in the hole, per "A Sourcebook on Solitary Confinement."

This intolerance can sometimes lead to outbursts of aggression while people are still in the penitentiary or when they're released back into public life, per PBS. As a result, many inmates who spent substantial time boxed up become repeat offenders. The hopelessness of this cycle is pretty apparent in that aggression often puts prisoners in solitary confinement in the first place, which then leads them to become more aggressive, keeping them in solitary confinement and ruining their ability to ever regulate their emotions and feel safe, as supported by a wealth of prisoner letters from the Silenced project. This doesn't just go for us plastic bipeds either, as Harry Harlow observed in his psychological primate studies that monkeys that were kept in solitary confinement often had violent tantrums once they were reintroduced to other apes.

Unintentional and Intentional Self Harm

Self-harm and suicide are incredibly common in solitary confinement. Prisoners from a study from New York University said that sometimes their abusive behavior is completely compulsive. "I cut my wrists many times in isolation. Now it seems crazy. But every time I did it, I wasn't thinking — lost control — cut myself without knowing what I was doing," one inmate said. Multiple prisoners from the Silenced project have written letters describing how they have tried to kill themselves but were unsuccessful due to the lack of resources to do so. Tunc Uraz, an inmate from the R.A. Handlon Correctional Facility, wrote, "l was screaming, shaking, babbling, and banging my head into the adjacent wall. I had made a noose out of bedsheets, but it was pointless, there was nowhere to hang it."

According to an article published in Science Direct, suicide is the second leading cause of death in all United States prisons. The rate is inextricably higher for prisoners in solitary confinement, one of the major causes being deprivation. The data stays pretty grim even after inmates are released from their institution after time spent in segregation, with the rate of suicide being high for those within the first year back to civilian life, according to a study in the PLoS One.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).