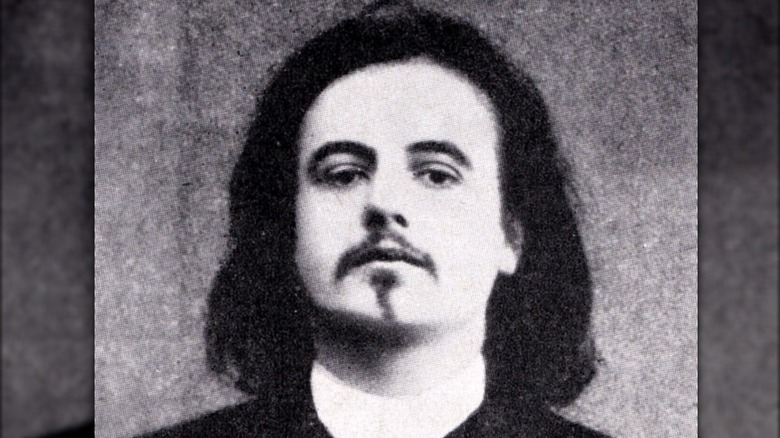

The Bizarre Life Of Symbolist Writer Alfred Jarry

Alfred Jarry isn't the most famous name in the world of literature. He is, for the most part, forgotten, remembered if at all on the basis of his most famous work, the play "Ubu Roi," a chaotic and decadent work of symbolist mayhem that generations of drama students are familiar with as, most often, a first-year script. Perhaps it deserves more recognition.

Born in the small French town of Laval, Mayenne, on September 8, 1873, Jarry became one of the most influential artists of the French symbolist movement, though his work came to be so unique as to defy such a rigid definition. His writing, including such strange novels as "Exploits & Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician" and "The Supermale" are some of the strangest of all time, while his Ubu plays have been identified by literary critics as influential forerunners of the Theater of the Absurd, prefiguring the work of Samuel Beckett and Eugène Ionesco and both the Dadaist and Surrealist movements.

But Alfred Jarry was a writer whose life and work were equally unconventional. He once proclaimed (per the University of Tulsa), "The work of art is a stuffed crocodile."

The schoolboy origins of Père Ubu

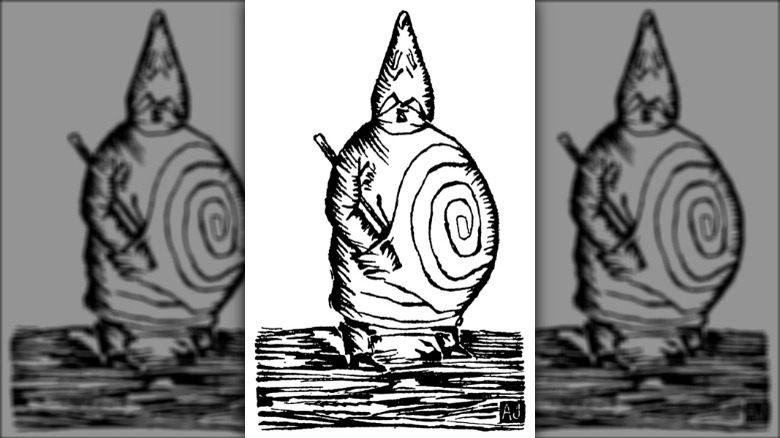

The titular character of Jarry's play "Ubu Roi," Pére Ubu, is a monstrous creation described by Britannica as "gluttonous, greedy, and ... cruel," but also ultimately a coward and a fool. Pére Ubu a barrel-bodied grotesque who, amid infighting with his wife, Ma Ubu, and his band of followers — or "lunatics" — kills the King of Poland and usurps the throne.

Ubu is a monster, but rather than a parody of, say, Napoleon Bonaparte, the character is reportedly derived from a man Jarry knew as a schoolboy: his physics teacher, Professor Hébert. According to Jarry scholar Roger Shattuck, Hébert was a sincere but incompetent teacher, whose lack of ability in controlling the class saw him roundly ridiculed by generations of students, who would pelt him with missiles in the classroom, and imitate him and write about him outside of it. And when Jarry came into contact with him, Jarry adopted him and his surrounding legends into his own imaginative world, basing upon him a trilogy of plays he would be working on throughout his short life.

But Professor Hébert was perhaps not only the original source material for "Ubu Roi." As Shattuck observes, the teacher's chaotic lessons also presented science itself — "my science of physics," as Hébert himself would call it — as a hubristic establishment, which, through its dry humorlessness, deserved to be knocked down. This would come to play a part in much of Jarry's later writing and the legacy he left behind.

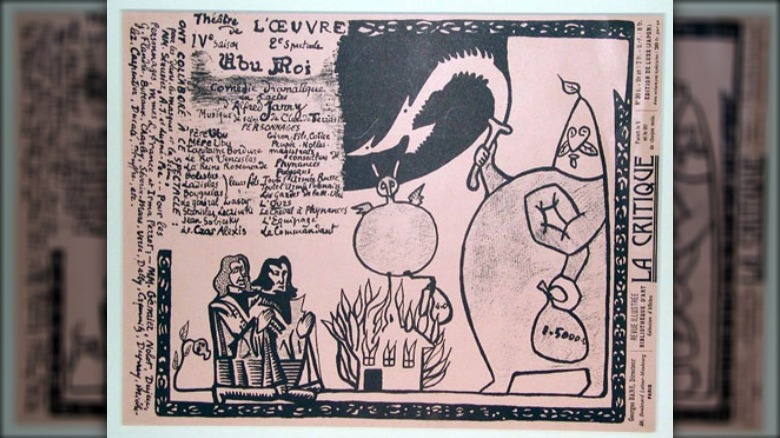

The play that caused a riot

While Alfred Jarry's chaotic masterwork "Ubu Roi" remains his best-known work, what is perhaps the best-remembered part of his life is the response the play received when it premiered in Paris in 1896. The event took place in December of that year at the Théâtre de l'Œuvre, a leading venue for innovative theater, with the production assisted by some of the top creatives of late 19th century Paris, including composer Claude Terrasse, who provided music, and artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who designed the set.

The play (posted at the Internet Archive) begins with a deliberate provocation: with no overture, the character of Ubu wheels out onto the stage and begins proceedings by bellowing a single word which, in the English translation, is sometimes rendered as "PS***." What followed was a deliberately obscene orgy of scatology and violence. Listed among the characters is a "disembraining machine," which stirred the audience into such a rage that a riot broke out in the theater (via The Paris Review), propelling the 23-year-old Jarry to literary stardom and provoking a widespread and heated debate over the future of the theater and of European literature.

As revealed by his own diaries, the Nobel Prize-winning poet William Butler Yeats was in attendance at the premiere of "Ubu Roi," and was apparently horrified by Jarry's vision for the future of art, causing Yeats to predict (posted by the University of Pennsylvania), "After us" — meaning, after the spiritualist symbolist movement — there would be "a savage god."

Jarry's subversive hedonism

Alfred Jarry scandalized ordinary people with his unusual appearance. He was small, but wore oversized clothing, a quirk unseen in such a primly-dressed era. He drew admiration from the literary circles he mingled with at various Paris salons for his originality and nonconformity. His literary friend and lover, the poet Léon-Paul Fargue, claimed Jarry "created a sensation with his hooded provincial cape and stovepipe hat, which was taller than he was and glistened like burnished metal" (via Roger Shattuck's "The banquet years: the arts in France, 1885-1918: Alfred Jarry, Henri Rousseau, Erik Satie, Guillaume Apollinaire," posted at the Internet Archive).

Other details of Jarry's appearance caused an uproar, including his constant use of a bicycle. As innocuous as that may seem today, the vehicles were a brand-new invention in Jarry's youth. The sight of him in his strange attire shuttling through Paris was, for many Parisians, an eerie sight.

Jarry was also a lifelong hedonist. He was a heavy drinker, particularly of absinthe. It is claimed he once roared through Paris on his bicycle with his face painted green, in celebration of the liquor he referred to lovingly as the "green goddess" (per the book "Absinthe — The Cocaine of the Nineteenth Century"). That is, if he could afford it, which, during long spells of abject poverty, he often could not. Instead, he drank ether, which had severe repercussions for his sanity and his health.

Inventing a new science

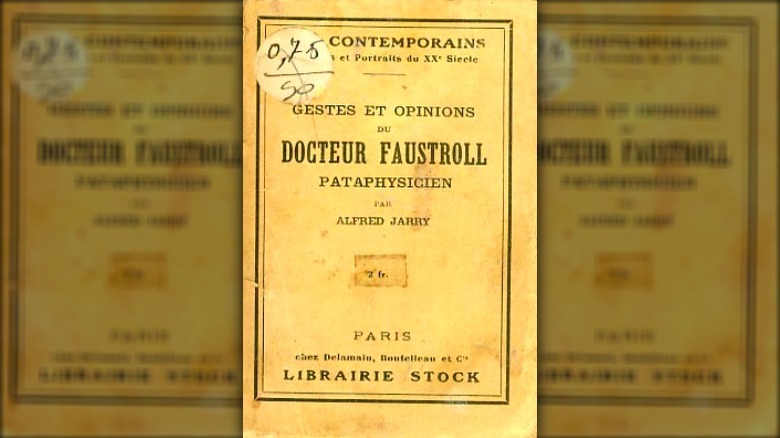

While Alfred Jarry's originality had many admirers — among them Pablo Picasso and the poet Guilliame Apollinaire — his strangeness and eccentricity in his personal life meant that forging a career as a professional and popular writer ran into constant difficulties. Jarry himself admitted as much in a handwritten note on one of his manuscripts of the novel, "Dr. Faustroll," which remained unpublished during Jarry's lifetime: "This book will not be published integrally until the author has acquired sufficient experience to savor all its beauties in full" (via "Selected Works of Alfred Jarry"). As Roger Shattuck notes in his introduction to the volume: "At 25 Jarry suggested he was writing above everyone's head, including his own."

"Dr. Faustroll" follows the adventures of the titular character, a scientist who was born at the age of 63 and who navigates both land and water in a giant sieve. But more importantly, the novel outlines many aspects of what Jarry named "Pataphysics," defined variously as "the science of imaginary solutions" and "the science of that which is superinduced upon metaphysics," but which is, in essence, a parody of scientific practices through which to offer a defamiliarized vision of the world.

Using the practice of Pataphysics, Jarry was able to describe a design for a convincing time machine, while at the end of "Dr. Faustroll," the title character — now dead but reporting back to the living from "ethernity" — outlines a mathematical formula which proves God exists as "the tangential point between zero and infinity." As Faustroll notes: "Pataphysics is the science..."

Possessed by Ubu

For many critics, the work and life of Alfred Jarry are inseparable; a continuous, relentless attack on the boorish, hypocritical, feckless affectations of bourgeois French society. While Jarry lived his life on his own terms, those terms were ultimately self-destructive. As Roger Shattuck wrote: "His life and his work united in a single threat to the equilibrium of human nature. He died at 34 in a gradual suicide by poverty, drink, and violated identity."

On the last point, critics have commonly claimed that Jarry was — like the writer Hunter S. Thompson in his gradual adoption of the semi-autobiographical character Raoul Duke — consumed by his own creation. In the years following the seismic impact of "Ubu Roi," Jarry is said to have taken on the characteristics of Père Ubu, terrorizing Parisians with a loaded pistol and reveling in his own gluttonous monstrosity, to the point at which his own personality was gradually erased. In a final performative action, it is said that his last words were a request for a toothpick.

In the end, Jarry, like Ubu, existed as what the Financial Times described as an "id unbound," though he was not the only person the character infected: per the same source, Picasso, a Jarry obsessive who came to wield his own gun for shocking effect, recited lines of Ubu's by heart and fired blanks at critics and pseudo-intellectuals. In 1948, admirers established the Collège De 'Pataphysique, to see that this underappreciated author remains a subversive force for modern times. Jarry — and Ubu — live on.