How The Death Of A New York Senator Impacted The Right To Die Movement

When we talk about the right to die in modern discussions, we're usually talking about the right of assisted suicide, or euthanasia. Currently, eight states and the District of Columbia have "right to die" laws on the books, which allow for terminally ill patients to choose to end their own lives (via World Population Review). Different organizations work to promote the right to die movement in the United States, including Death with Dignity, which describes the goal of right to die legislation as ensuring that "people with terminal illness can decide for themselves what a good death means in accordance with their values and beliefs" (via Death with Dignity).

However, the phrase "right to die" once had very different connotations. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, the right to die movement was focused on something that we might now take for granted: the right, if you experience irreversible injuries like severe brain damage, to be taken off life support and choose to die naturally (via the Online Journal of Issues in Nursing).

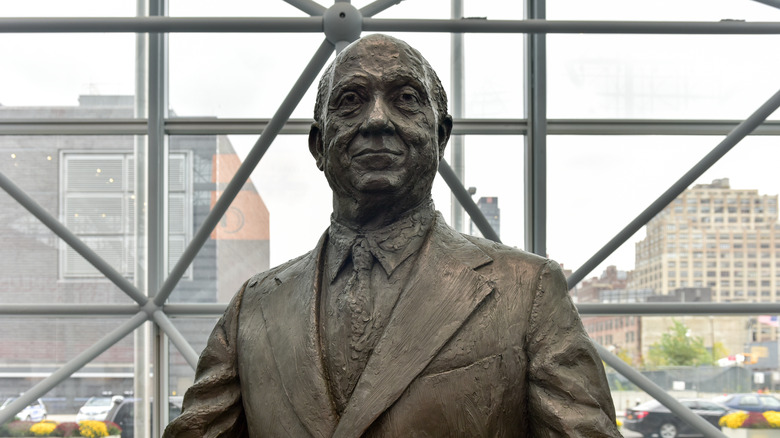

Many different advocates and politicians contributed to enshrining that right. But one particular man, Senator Jacob K. Javits, had a larger role than most.

Who was Senator Javits?

Senator Javits was one of the longest-serving New York senators of all time, having been first elected to office in 1956 and staying in the Senate until 1980, according to the New York Daily News. Previously, Javits had worked as a lawyer and had served in World War II. As a senator, Javits wasn't content to sit back and let his colleagues direct the path of the nation; he was part of many groundbreaking legislative pieces, supporting the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1973 War Powers Act (via the United States Senate).

In his personal life, Javits was married twice, once in the early 1930s and later in the 1940s, according to the Daily News. Javits was known for his confidence and boldness, even reportedly calling himself a political "institution." But despite his long legacy, Javits was defeated for a fifth term in 1980, not long after he shared that he had a severe illness: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS.

What is ALS?

ALS is a degenerative disease in which the muscles don't work properly (via ALS Association). Also called Lou Gehrig's disease, ALS is a disease which often shows up relatively late in life. Risk factors can include certain genes that can be shared within families, but in most cases, it's not clear why someone may develop the condition (via ALS Association). Treatments for ALS can include medication, heat therapy, and, in the later stages of disease, mobility tools like wheelchairs, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Once someone is diagnosed with ALS, their life expectancy is around five years, according to the ALS Association, and the disease is currently incurable. Approximately 5,000 people are diagnosed with ALS each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), meaning it is a relatively rare condition compared to other degenerative diseases, like Alzheimer's, which affects around 500,000 new people each year (via Bright Focus).

Senator Javits shared his experience with ALS

Senator Javits was a known champion of equality during his long political career, according to the United States Senate, and he carried on that legacy after he was diagnosed with ALS. Though Javits lost his 1980 bid for a fifth term, he returned to Congress in 1985 to speak about the concept of death with dignity, imploring the members of the House of Representatives to ensure that very sick individuals would be allowed the option of a natural death (via United Press International).

At that time, there were not universal standards across the country regarding advance directives and withdrawing support from grievously injured or sick individuals, according to the Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. Just a few years earlier, in 1983, a case had caught national attention when a rehab hospital refused to withdraw life support from a young woman in a vegetative state. It and other cases were very controversial and got many people speaking about the topic of advanced directives.

How the federal rules changed

In his speech before Congress, Senator Javits asked the House representatives to reconsider their reasons for believing death to be an inherently bad thing, according to United Press International. "Birth and death are the most singular events we experience," he said. "Therefore the contemplation of death as birth should be a thing of beauty and not of ignobility."

Though Congress did not respond with any bills in 1985, five years later, Congress passed the Patient Self Determination Act (via Congress). The law worked toward creating more comprehensive policies about end-of-life care, including by specifying that certain healthcare organizations, like nursing facilities, were required to give their patients information about advanced directives and to ensure they had an opportunity to complete one, if desired.

Unfortunately, Javits was not able to see the bill become a law himself. In 1986, less than a year after speaking in front of the House of Representatives, Javits died due to complications from ALS (via Daily News).

What the right to die movement looks like now

Today, an increasing number of states have passed "right to die" or "death with dignity" laws (via Compassion & Choices). Those states include Oregon, Washington, Montana, Vermont, California, Colorado, Hawaii, New Jersey, Maine, and New Mexico, as well as the District of Columbia. Some countries also have death with dignity laws, including the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Colombia, and Canada (via the Annals of Palliative Medicine).

The exact content of these laws can vary depending on location, according to the Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. Most of these statutes allow physicians to prescribe fatal medications that a terminally ill individual can choose to take if desired (via Slate). But different states have different rules on who is eligible and on the potential waiting periods that people may have to undertake. For instance, until 2019, all terminally ill individuals wishing to end their lives in Oregon had to wait at least 15 days to do so, according to Death with Dignity. That rule can now be overridden in some situations.