What The Making Of We Are The World Was Really Like

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation reported once that Ethiopia averaged one famine per decade from the 1600s to the 1800s. Civil wars, forced confiscation of crops, and natural disasters have conspired against the nation time and again. But the famine that struck in the 1980s was unprecedented in its magnitude. Relief commissioner Dawit Giorgis told the BBC that up to a third of the population was affected and that he saw areas where hundreds died every day. The government of the time was unable and unwilling to adequately address the famine, which became an international story not through their efforts, but from reporting by the BBC.

The scale of the tragedy moved many to lend their support. Foreign governments flew in aid, reporters continued to shine a light on the famine, and celebrities took up the cause en masse. This was the age of the charity telethon, the fly-ins to raise awareness, and the musical numbers made to generate relief funds. A small fleet of British and Irish singers were brought together for a recording of Bob Geldof and Midge Ure's "Do They Know It's Christmas," written to express moral outrage and raise a few thousand pounds for charitable efforts in Ethiopia. Per U Discover Music, it raised £8 million in 1984 alone.

Inspired by "Do They Know...," Harry Belafonte decided to create the American equivalent, a charity record assembling all the top American artists of a generation (per The Independent). The recording, "We Are the World," was a juggling act of schedules and egos that raised even more than its inspiration. Here's what went into making it.

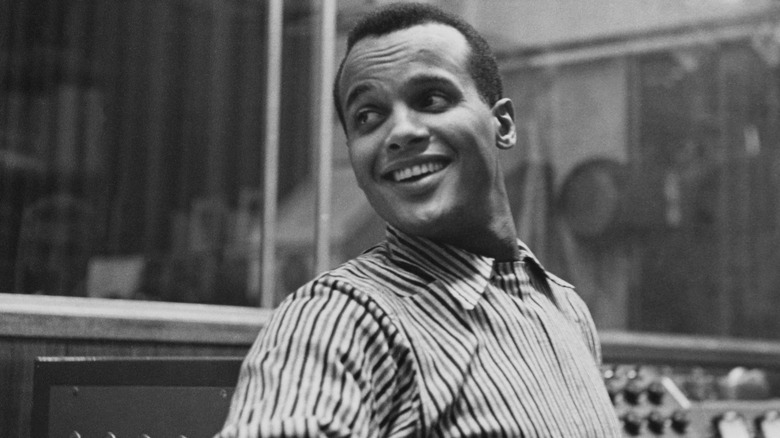

Harry Belafonte initiated the project

According to The Independent, Harry Belafonte started his recruitment drive for what became "We Are the World" in December 1984, just after "Do They Know It's Christmas" hit No. 1 on the U.K. music charts. Belafonte had a sense of moral outrage about the Ethiopian famine to match Bob Geldof's. He referred to it as a "holocaust" in a Jet interview and accused those in power of exploiting the famine for their own gain rather than providing relief. "Death of people of color is an accepted state," he added. "If this had happened in Europe, there would have been a much swifter response. But, there's something dismissible about the Third World."

Per the Los Angeles Times, Belafonte initially wanted to organize a benefit concert, not a record. He reached out to manager Ken Kragen, who managed many of the hottest U.S. musical acts of the 1980s. Kragen felt that a concert at an appropriate scale couldn't be organized in time. It was his idea to do a single song instead.

Despite his passion for the cause, Belafonte was not involved in writing the proposed song, and there's no indication that he sought to be a part of the writing team. In fact, the Los Angeles Times reported that Belafonte, Kragen, and producer Quincy Jones (the third chief organizing force behind "We Are the World") seemed at pains not to take too much credit or garner too much personal publicity for the record. "If you could talk about the project and forget us, that would be nice," Kragen told the paper.

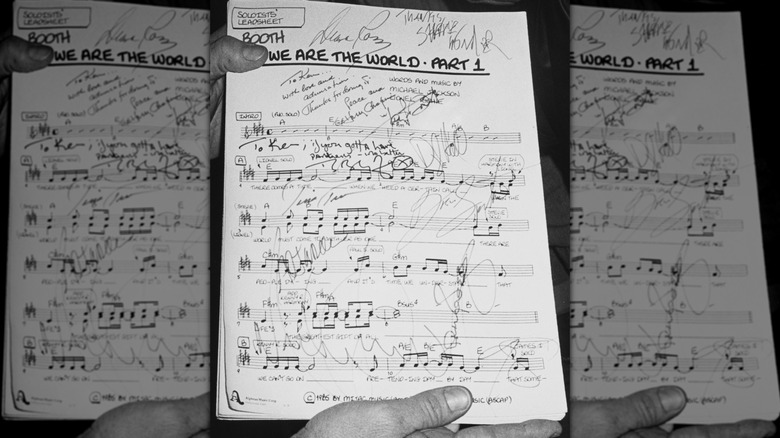

Lionel Richie and Michael Jackson wrote the song

Having set the project's dimensions as a record rather than a concert, Ken Kragen immediately began recruiting his clients. Among them was Lionel Richie, who Kragen wanted to write the song in collaboration with Stevie Wonder (per The Independent). Contacting Wonder was left to Richie, who tried all night after Kragen's call to reach his fellow singer without success. He ended up getting a hold of him through his wife, who bumped into Wonder while out shopping the next day.

While Richie's wife got Wonder to return her husband's messages, Kragen recruited Quincy Jones as producer of the record and tasked him with bringing on board one of the biggest pop stars of the 1980s: Michael Jackson, fresh off of "Thriller." Jones found him not only willing to participate but eager to be part of the writing team. And with Wonder suddenly unavailable, "We Are the World" became a joint effort by just Jackson and Richie, who studied national anthems for a guide.

At a MusiCares event in 2016 (via Billboard), Richie shared how the writing process was eventful. For three days, he was distracted by a yapping dog, a Mynah bird shouting at said dog, and an albino python that scared Richie to death. "I know you want a spiritual tale about how we brought this song you," he said, "but that's how it was." LaToya Jackson claimed (via J. Randy Taraborrelli's "Michael Jackson: The Magic, The Madness, The Whole Story, 1958-2009") that Jackson wrote everything but a handful of lyrics, but neither Jackson or Richie discussed the division of labor or due credit.

Prince (among other artists) refused to participate

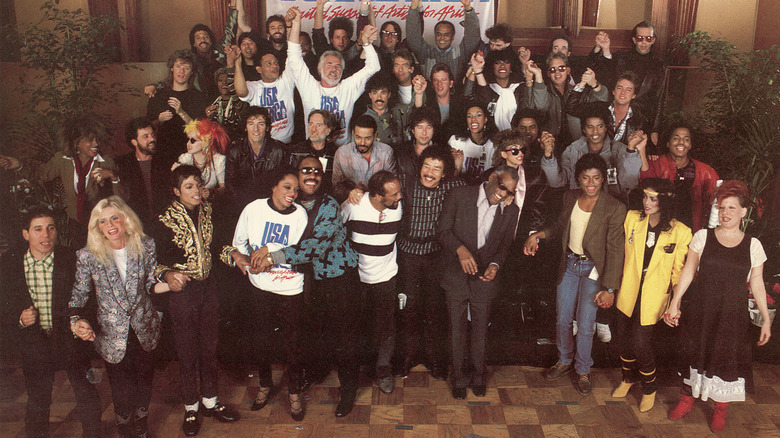

To maximize the chance of getting as many artists as possible in the recording studio at one time, Ken Kragen proposed recording "We Are the World" after the American Music Awards when the cream of the American pop scene would be together in Los Angeles anyway (per The Independent). That gave him about a month from the project's inception to recruit as many top-listed acts as possible. Besides the artists responsible for organizing and writing the song, Kenny Rogers, Kim Carnes, and Lindsey Buckingham signed up almost immediately.

But Kragen credited Bruce Springsteen with opening the floodgates. Once he committed to being part of the record, so many celebrities expressed interest that Kragen had to turn people away. "I wanted about 20 people, we ended up with 45," he told The Independent. Participating artists (per USA Africa) included Ray Charles, Diana Ross, Willie Nelson, Tina Turner, and even a few names from outside the music world, like Dan Aykroyd.

Nearly every major name in popular music from the 1980s took part in "We Are the World," but there were exceptions. Kragen later regretted not approaching folk singers John Denver and Joan Baez. Eddie Murphy and Madonna turned down the offer, and a part set aside as a duet for Michael Jackson and his rival Prince had to be reworked at the last minute when Prince decided not to show up. His refusal (and his partying away at a nightclub instead) generated some harsh feelings, though he did later contribute a song as the B-side to the album release.

Recording the song demanded that the stars 'check their egos'

The artists assembled for "We Are the World" were dubbed USA for Africa. The supergroup assembled on January 28, 1985, for recording, under Quincy Jones's supervision. According to the Los Angeles Times, there was no rehearsal, and no room for negotiating arrangements, lines, and seating order. "You can't be democratic when you have that many stars working together," Jones told the paper. "If you try to be democratic, you're in for chaos."

Jones was recruited, in part, because he'd worked with many of the big names involved in "We Are the World" and was considered a deft manager of stars and their attitudes. For good measure, a sign was placed over the studio door that read "check your egos at the door." But egos did threaten the whole endeavor when Kragen was told through a manager that the rock artists — no names were specified — didn't like the song or having to be in close proximity to pop artists. The threat fell apart when Bruce Springsteen made it plain he was going to participate. "If The Boss was there, you had to remain," said Kragen. "He really saved the day."

It was an all-night recording session

Recording for "We Are the World" began at 10:30 in the evening, with the talent on one soundstage and over 500 guests watching via a large screen on another (per The Independent). Bob Geldof, part of the team behind the project's British counterpart, was on hand to reiterate the plight of Ethiopia. The recording was arranged so that the chorus was the first part recorded, lest some of the bigger stars take off as soon their solo tracks were laid down.

The recording began with everyone in good spirits. Singers laughed and kidded one another as they worked through all the parts. But tempers flared when, at 1 a.m., Stevie Wonder tried to insert lines in Swahili to the chorus. The suggestion was meant to replace some nonsense words that Geldof thought could be offensive, but he didn't like the replacement either; Swahili, he pointed out, wasn't even a language used in Ethiopia. Several of the stars weren't happy at the thought of learning a foreign lyric after singing all night, and Waylon Jennings even briefly walked out. "One world, our children" was used as a compromise.

The solo lines weren't reached until 4 a.m. To save time, they were done all in one go, with 21 microphones set up around the studio. The session finally wrapped at 8 a.m. on January 29. Looking back for Voice of America, Lionel Richie called the session "the best that could ever happen," the one time those artists made a concerted joint effort to use their fame for such a cause.