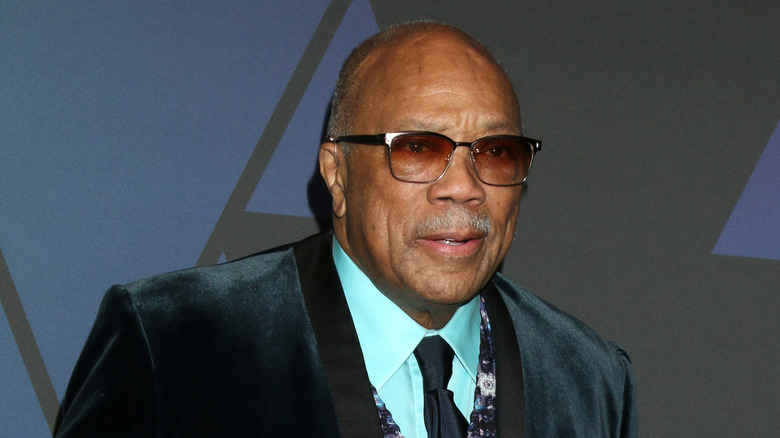

The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Quincy Jones

There are few figures in the world of music with a discography as rich and a reach as wide as Quincy Jones, the legendary musician, producer, and arranger who, after cutting his teeth as a band musician in the 1950s, went on to work with some of the biggest names on the planet. Jones has won countless awards for his work with acts such as Frank Sinatra and Aretha Franklin, though it was perhaps as the producer for the King of Pop himself, Michael Jackson, that Jones reached his greatest heights. His role as a guiding hand on both "Thriller" and "Bad" ensured that the two albums became some of the biggest-selling in music history; in fact, "Thriller" is still considered the best-selling studio album of all time, having sold more than 47 million copies worldwide, according to Paste.

The winner of an incredible 27 Grammy Awards with 79 nominations over the course six decades, Jones' career is now regarded as one of the most high-flying in the whole of American music history. But despite Jones' ample determination and an undeniable wealth of talent, his path to musical glory was a tough one –- and things didn't exactly get better for him in terms of his health and his personal life once he hit it big. Here are the tragedies, trials, and tribulations that music maestro Quincy Jones has faced during his lifetime.

Jones was born into poverty

In the current music landscape, many big names get their start in the business through family connections, or because they're privileged enough to take a shot at an industry that only becomes lucrative once an artist becomes established.

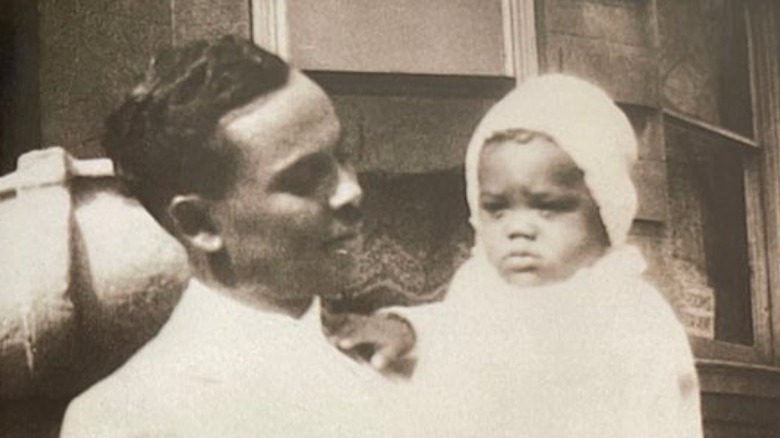

Quincy Jones, however, had no such luxuries. Born in Chicago, Illinois, on March 14, 1933, Jones' parents, Quincy Sr. and Sarah Jones, had traveled to the Windy City in search of work, having left their home in the South -– as well as the racial segregation that was still enforced in the Southern states at the time -– behind them, according to biographer Linda N. Bayer.

However, Chicago in the early 1930s wasn't the haven the young couple had expected it to be. Around the time of Quincy Jr.'s birth, America was in the grip of the Great Depression, having been brought to its knees financially following the stock market crash of 1929. Though Quincy Sr. was a trained carpenter, he struggled to find work to support his young family, and his son was born into a life of poverty and need on the South Side of the city.

His mother had mental health problems

Such financial strain is also the cause of great emotional and mental stress for many families, as was the case for the Joneses.

As the hardships of the Great Depression continued to bite, Quincy Jr.'s mother, Sarah, struggled, with circumstances exacerbating mental illness that, according to Linda N. Bayer's 2001 biography, started to afflict Sarah shortly after the birth of her son. In interviews quoted by Bayer, Jones recalls various episodes of his mother's unstable behavior during his childhood, including an incident when she smashed a birthday cake during a party in the family's backyard. Sarah was hospitalized for long periods of Jones' formative years, which had repercussions on how the child related to his mother. As quoted in Bayer, as a child Jones and his siblings were confused by their mother's behavior and long absences from the family home, and blamed her for it. It took many decades for the musician to come to terms with the fact that Sarah was a victim of her own mental illness.

Nevertheless, Sarah was a talented woman who was credited with giving Jones his innate gift for music. She was a devoted Christian who played religious music on the piano, and in her later years she became a noted supporter and patron of the arts in Seattle, where she moved in 1943. She died in 1999.

If you or someone you know is struggling with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

Chicago was a violent place to grow up

The South Side of Chicago where Jones grew up was, by his own account, an impoverished area rife with gang warfare. He frequently saw violence between gangs and police officers.

Via Linda N. Bayer's biography, Jones' brother Lloyd recalls the graphic violence that he and his young brother were exposed to in their everyday lives, including the sight of a murdered man hanging from a telephone pole, with the murder weapon –- an ice pick –- still protruding from the body. Such was the violence that the young Jones brothers became hardened to it. As Jones later recalled, he once saw a local man shot by a police officer at a neighborhood drug store, but the incident barely seemed to affect him; per the same source, Jones claims he "accepted it as part of Chicago life."

But as a child, Jones was also a victim of violence himself. As he told Rolling Stone in 2010: "I got a switchblade through my hand — they nailed me to a fence when I was seven years old. I was on the wrong block. Ice pick in the head, so s*** ... I know Chicago, man."

His father suddenly remarried

While the world outside the family home was desensitizing in its chaos and violence, developments within the Jones family were also becoming tumultuous for Quincy and his brother Lloyd.

According to Linda N. Bayer, in 1943, Quincy Jones Sr. (pictured) decided to remarry, having fallen in love with the mother of one of Quincy Jr.'s neighborhood friends while his own wife, Sarah, was hospitalized as a result of her ongoing mental illness. Subsequently, Quincy Sr. moved his sons and his new wife, Elvira, to the Seattle area, along with Elvira's own children. Though the family escaped the violence of Chicago, living conditions were cramped, with the merged family's ten members living and sleeping in just two rooms. Per GQ, Jones initially felt alienated in his new home city, being the only Black child in his class at school and having been used to greater racial diversity in Chicago. However, in his later years, Jones credited his father's moving the family to Seattle as the right decision for the family.

Upon being discharged from the hospital, Jones' mother, Sarah, also moved close to Seattle, allowing her to remain close to her children.

Quincy Jones was traumatized by a car crash at age 14

Though Quincy Jones was beginning to find his feet as a musician in his teenage years, his life still took tragic turns. According to CNN, when Jones was 14, he was a passenger in a traffic collision in which four of his friends were tragically killed.

The trauma of the incident stayed with Jones and affected him throughout his life. In 2007, the musician gave an interview to Fortune's Sue Calloway, as she was test driving the $8 million Maybach Exelero around Beverly Hills (via CNN). In an animated exchange, Jones reportedly yelped repeatedly as Calloway hit top speeds in the 700-horsepower supercar, telling her that her driving reminded him of that of his close friend, the actor Steve McQueen.

But Jones' fear of driving wasn't reserved for high speeds. As he later told the Associated Press, his nerves behind the wheel meant that he was never able to get a driver's license. Jones recalled: "I took a driving lesson. My teacher — he was from Yugoslavia — said, 'Man, I'm giving you your money back. We don't need another maniac on the road' ... I was trying to stop on the downbeats at the stop lights" (via Vancouver City News).

He had a teenage heroin habit

It is possibly not a coincidence that when he was 15 — the year after the fatal accident that traumatized him so badly — Quincy Jones began using heroin.

The use of drugs such as heroin in the jazz communities of the 1940s, '50s, and '60s has been well documented by historians, academics, and the musicians themselves. In a 2018 interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Jones said he was introduced to the drug by Ray Charles (pictured). Jones explained he had met Charles at the start of his jazz career, at the age of 14. Charles was four years older than Jones.

Per NME, Jones recalled that he would be playing in various jazz clubs with Charles, seeking out "bebop jam sessions." None of the musicians would get paid, but at the end of the session, his friends –- including Charles –- would gather in the corner to take heroin. "I just snuck in the line and got me a little hit," Jones said. In the same interview, the musician claimed that their drug dealer was a man named Detroit Red; as the NME notes, this is a known alias of the human rights activist Malcolm X.

Though Jones became addicted, he soon overcame his addiction after a fall down a flight of stairs while high convinced him that he needed to go straight (via Vibe).

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

He had a heartbreaking encounter with Charlie Parker

Quincy Jones' natural talent meant that he mingled effortlessly with other great musicians such as Ray Charles in his formative years. But when it came to meeting older jazz heroes, his experiences weren't always so enjoyable.

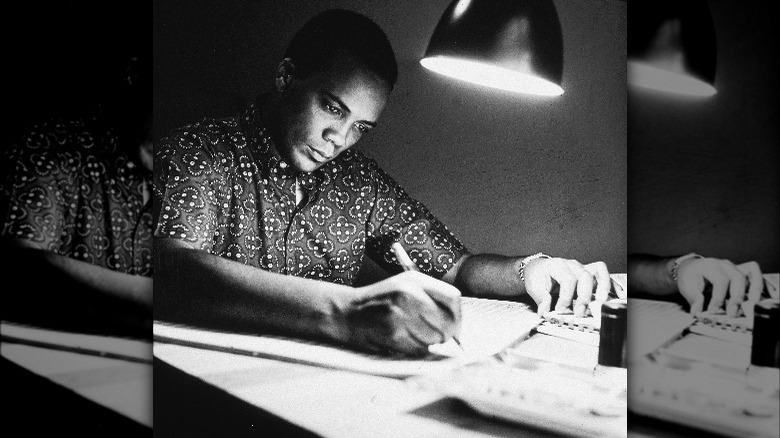

Linda N. Bayer recalls a heartbreaking story from 1951, when Jones, then 18, was in New York working as an arranger for the musician Oscar Pettiford, earning $17 per song. After one session, Jones and Pettiford explored the city's jazz clubs, including the legendary Birdland club, named after Jones' hero, the bebop innovator Charlie Parker.

One night, Jones was lucky enough to meet Parker and hang out with him at another notable jazz spot, Big Nick's. Eventually, Parker suggested that he go and buy them all some "weed." Trying to impress Parker, Jones gave the older musician all the money he had: about $20. But Parker never returned, leaving the young Jones humiliated and crying on 139th Street without a penny to his name.

Quincy Jones faced the reality of segregation

Throughout the 1950s, Quincy Jones earned a living as a touring musician, playing scores of dates across the United States as a trumpeter in vibraphonist Lionel Hampton's big band. As he recalls in his autobiography, "Q," during these years Jones became so au fait with stage performance –- both the music itself and with pre-show rituals such as costume and hair maintenance -– that the majority of his mental energy was taken up with finding women in the audiences to hook up with after each show.

But while Jones was learning to enjoy the hedonistic perks of life as a 20th-century touring musician, his travels through the South –- particularly in the Carolinas -– also exposed him to the harsh realities of segregation, which was still enacted in many Southern states in the 1950s. Per Linda N. Bayer, the band arrived in a small Texas town one night to discover an effigy of a Black man hanging from a lamp post. And while Jones' veteran bandmates tried to assure the young Jones that even the biggest Black music stars of the day learned to deal with segregation and racism, such incidents reportedly precipitated Jones' growing interest in leaving America in favor of Europe, where he soon toured extensively.

He suffered a brain aneurysm at his peak

Quincy Jones' career went from highlight to highlight throughout the 1950s and '60s. He won his first Grammy Award in 1963 as the arranger on Count Basie's hit "I Can't Stop Loving You," and grew in stature thanks to his close association with huge names such as Frank Sinatra, for whom he worked as both a producer and an arranger throughout the '60s (per Grammy Awards).

However, while Jones was working with some of the biggest names in the business and making a name for himself as a performer in his own right, his career threatened to come to a grinding halt in 1974, when he suffered a near-fatal brain aneurysm.

Jones recalled in a Facebook post in 2018: "[I]t felt like a shotgun was fired inside of my head. While operating for 7.5 hours, my doctors discovered a second aneurysm that was ready to blow, so they had to schedule a second operation." Though he survived the ordeal, Jones was unable to play the trumpet after his illness, in case the strain of blowing into the instrument should aggravate his condition; as he later told the LA Times: "The main artery in my brain is held together with a clip. Deep-sea diving and playing the trumpet blow that thing straight off."

Nevertheless, he soon returned to work and went on to enjoy some his greatest musical successes, which included his multi-platinum-selling collaborations with Michael Jackson.

Quincy Jones' living memorial

In his 2018 Facebook post, Quincy Jones recalls that the outlook initially "didn't look too promising" after his 1974 illness, and estimates that his chances of survival at the time were in the region of 100 to one.

With Jones' death seemingly imminent –- according to The Guardian, doctors who shaved his head prior to his operation kept his hair, in case it had to be reattached for an open-casket funeral -– his friends and family organized a vast memorial in his honor. And when, against all odds, Jones survived his ordeal, the memorial went ahead anyway, with a special guest: Jones himself.

"My doctor said I could go, but I would have to remain calm," Jones recalled (per Newsweek). "That was hard to do with Richard Pryor, Marvin Gaye, Sarah Vaughn and Sidney Poitier singing your praises ... my neurologist sat next to me to make sure I didn't do the wrong thing."

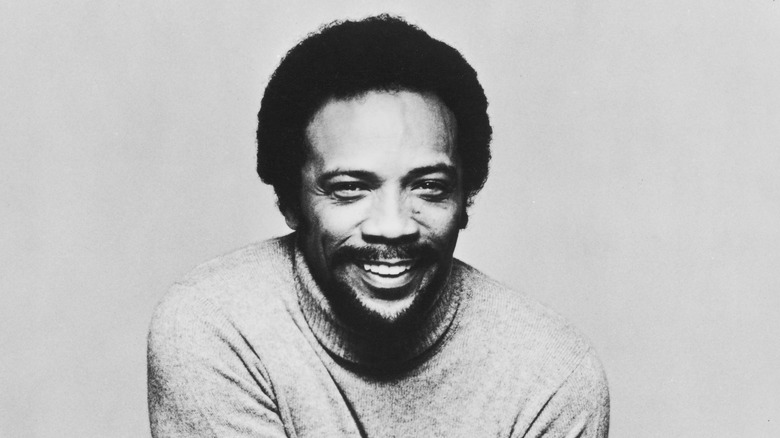

His workaholism damaged his relationships

It is perhaps no surprise to learn that an artist as prolific as Quincy Jones –- whose discography runs to more than 400 releases as a performer, producer, arranger, or composer, according to Discogs -– is a compulsive workaholic.

According to biographer Linda N. Bayer, the total devotion to music in his early years had a ruinous effect on many of his family relationships, with the musician's numerous long absences from the family home leading to a series of divorces. Bayer argues that Jones may have put his music before family life as a result of the pain he still felt as a result of his own difficult upbringing, especially his mother's absences.

Though he was often a distant father -– he has seven children with five women, including three ex-wives -– in his later years, Jones sought to reconnect with his children, and today they enjoy a close relationship.

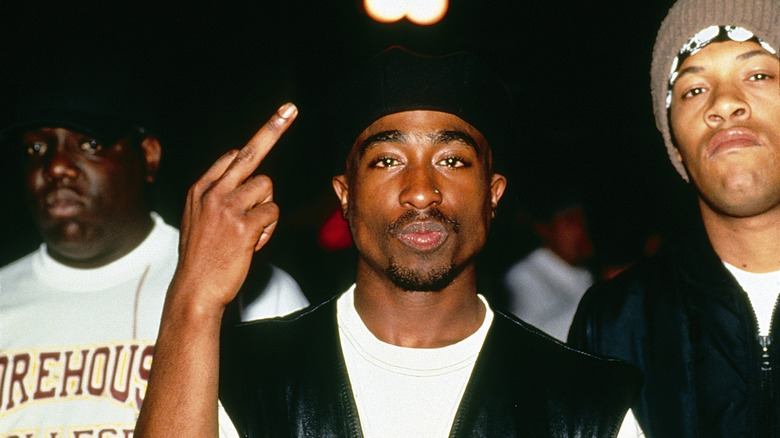

Jones' feud with Tupac Shakur

By the 1990s, Quincy Jones –- with a wealth of work and prestigious awards to his name -– was considered one of the elder statesmen of music. However, he did find himself running into controversies, most notably with regard to a feud with one surprising figure: the West Coast rapper Tupac Shakur.

In 1993, Shakur gave an interview with Source magazine, in which he accused Jones of being a sell-out, criticizing the veteran musician for having interracial relationships and children, according to Jones' autobiography, "Q". Jones was incensed, while commentators branded Shakur a hypocrite, as he had recently had a much-publicized relationship with pop musician Madonna. Source published an open letter from Jones' daughter Rashida criticizing Shakur's comments, and further letters from white women highlighting their own liaisons with Shakur seemingly vindicated Jones.

And in a strange twist of fate, Jones and Shakur were drawn even closer when, in 1996, the rapper began a relationship with another of Jones' daughters, Kidada, having apologized to her for his comments about her father after meeting her in a club. As Kidada recalls in "Q," she was hanging out with her new boyfriend one night when her father appeared and took Shakur away for a talk, telling him: "I need to kick it with you for a minute." The two hugged it out, and Kidada and Shakur continued their relationship until he was tragically shot and killed in September of that year, aged 25.

Quincy Jones: still controversial

But as the years rolled on, Jones showed that he, too, was able to cause a stir. In 2018, two rambling interviews he gave with GQ and Vulture saw him dishing the dirt on several of his contemporaries.

Speaking to Vulture's David Marchese, for example, Jones derided the Beatles –- yes, the actual Beatles –- as "the worst musicians in the world," adding that Paul McCartney "was the worst bass player I ever heard. And Ringo? Don't even talk about it."

More controversial, however, were comments Jones made concerning the sex lives of celebrity friends Marlon Brando and Richard Pryor, whom he claimed were lovers, causing a backlash from Pryor's daughter (per People).

Jones later apologized for his comments on Twitter, calling his outbursts "word vomit" and describing himself as an "85-year-old bow-legged man who is still learning from his mistakes." His apology was apparently prompted by his daughters, who, according to Jones, "aren't scared to stand up to their daddy."