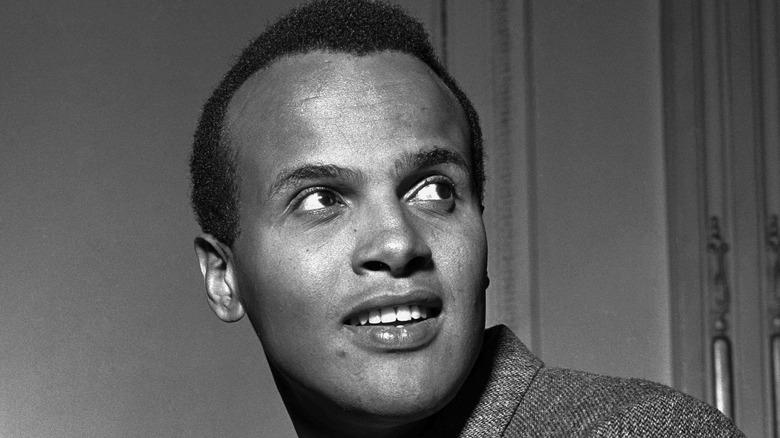

The Untold Truth Of Harry Belafonte

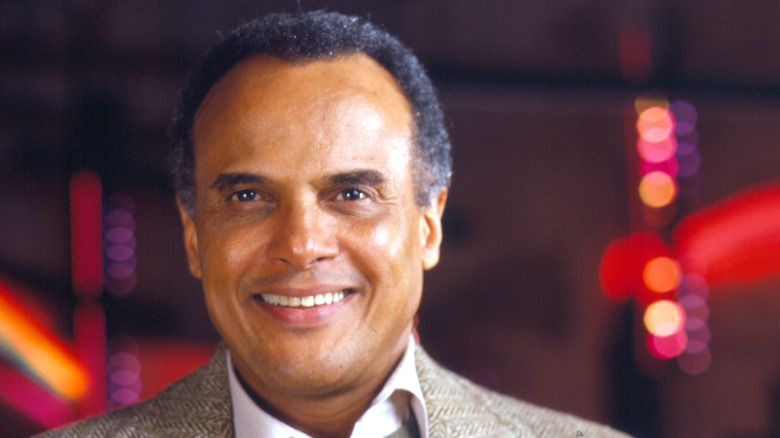

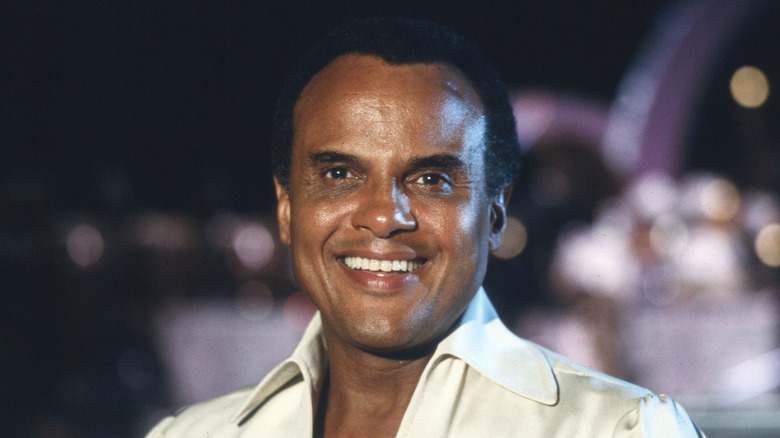

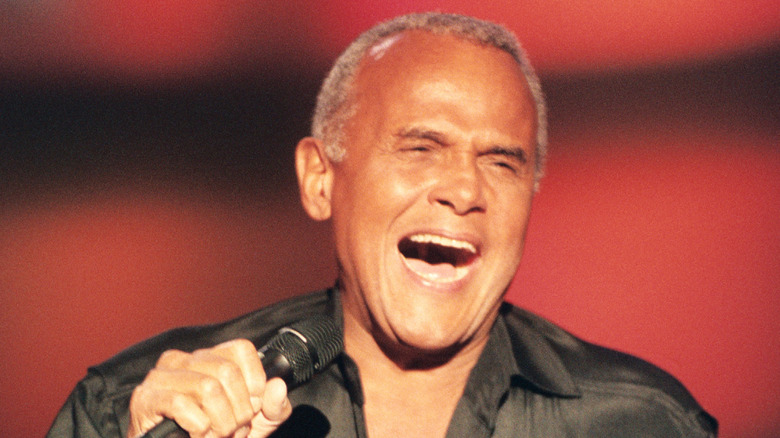

Harry Belafonte was arguably the most successful Jamaican-American artist in music history. Born to Jamaican parents, Belafonte spent several years in boarding school in Jamaica before high school, per the African American Registry. Nearly two decades later came the 1956 release of his breakthrough album, "Calypso," which popularized the Caribbean calypso genre of music among American and international audiences. According to Black History, "Calypso" was the first album by a solo artist to sell over a million copies. The album also earned Belafonte the nickname "King of Calypso."

But Belafonte did not always intend to be a calypso singer. In fact, his initial sights weren't set on music at all; he was an actor first and foremost. In addition to his work in music, Belafonte was an actor on stage and screen, starring in movies such as "Carmen Jones" and "Island in the Sun." He was also behind the scenes of some of the foremost activism of the 20th century.

Harry Belafonte served in the Navy during World War II

He was born Harold George Bellanfanti Jr. in 1927, reports The New York Times. His father, Harold George Bellanfanti Sr., was a cook in the British Navy, per the African American Registry. Harry followed in his father's footsteps at age 17, when he dropped out of George Washington High School and joined the United States Navy during World War II. The Navy was segregated at the time of the younger Belafonte's service in 1944.

That year, two military ships loaded with ammunition exploded and killed 320 people, most of whom were Black. "It was the worst home-front disaster of World War II," Belafonte told the Los Angeles Times, "but almost no one knows about it or what followed." What followed was that Black seamen refused to keep handling ammunition in such unsafe, segregated conditions. Fifty of them were sentenced to prison. "The Port Chicago mutiny was one of America's ugliest miscarriages of justice, the largest mass trial in naval history, and a national disgrace," Belafonte said.

Once he completed his service in 1945, Belafonte returned to New York to work in maintenance. He then used the G.I. Bill to pay for his classes at The New School Dramatic Workshop, alongside the likes of Marlon Brando and his lifelong friend Sidney Poitier, per Black Past.

Early in his career, Harry Belafonte tried out pop, jazz, and folk

Before Harry Belafonte became widely known for popularizing the calypso genre stateside, he dabbled in several different musical genres. While struggling to get his acting career off the ground, Belafonte hung around the Royal Roost jazz club in Manhattan, according to Jazz Times. He worked up the courage to ask the club's booking agent, Monte Kay, for a gig, and Kay agreed. As Belafonte's opening performance began, he was joined onstage by jazz greats Tommy Potter, Max Roach, and Charlie Parker. Belafonte was signed to Capitol Records shortly thereafter, but his early singles saw little success.

Still, before long, Belafonte was performing in upscale venues like Miami's famous Five O'Clock Club, crooning popular tunes onstage in front of primarily white audiences. It was around this time that he experienced firsthand the racism that even highly talented and successful Black musicians were subjected to in segregated America. He quit his Five O'Clock gig within a week.

That same year, Belafonte took an interest in folk music, learning many classics through the Library of Congress archives of American folk songs, per Britannica. In the mid-1950s, he kicked off a string of hit folk albums with the releases of "Harry Belafonte" and "Mark Twain and Other Folk Favorites."

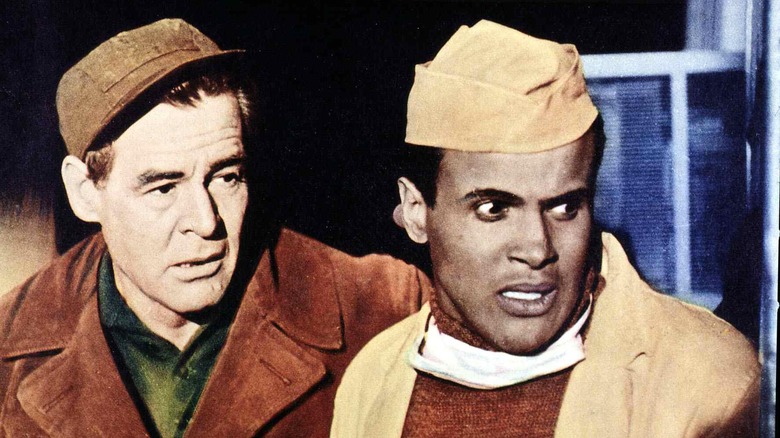

His film career spanned seven decades

Harry Belafonte may have had music in his blood, but he was bit by the acting bug long before he found fame as a musician. Speaking with NPR in 2011, he remembered how the stars lined up one day while he was working as a janitor's assistant in an apartment building. ("The job could not be considered artistic, but I did the job artistically," he said.) As a gratuity from a tenant, he received a pair of tickets to a stage production at Harlem's American Negro Theater — and it was there, he said, that "the universe opened for me ... When the curtain opened and the actors walked onstage, the evening overwhelmed me. And I decided with any device I could possibly find, I wanted to stay in this place."

Belafonte would indeed make his way to the Broadway stage, but only after becoming a successful recording artist — and using his startling good looks and charisma to land prominent roles in feature films at a time when few Black performers were afforded that opportunity. Per IMDb, his first role was in 1953's "Bright Road" opposite Dorothy Dandridge; in a film career that spanned seven decades, he would work with such icons as Joan Fontaine ("Island in the Sun," 1957), Sidney Poitier ("Buck and the Preacher," 1972), John Travolta ("White Man's Burden," 1995) and legendary director Spike Lee, who cast Belafonte in his final role, as an elderly civil rights leader in 2018's "BlacKkKlansman."

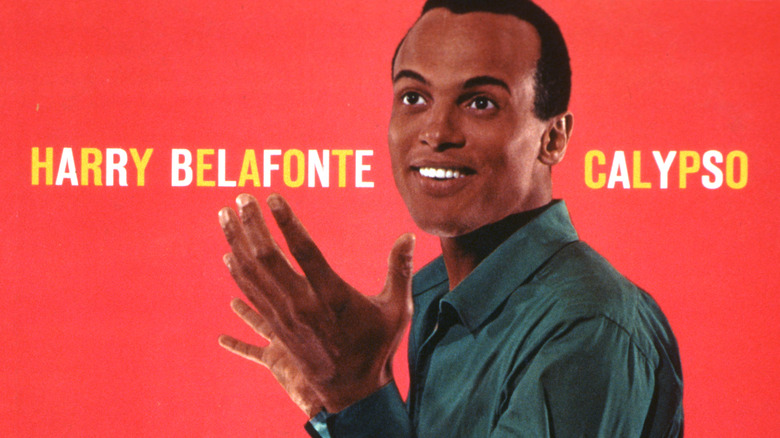

His breakthrough album was a record-setter

As documented in an essay by Judith E. Smith for the Library of Congress, the astonishing success of 1956's "Calypso," Harry Belafonte's third album, was due to a combination of factors. Belafonte had gained national recognition through nightclub and stadium tours, his Tony-winning Broadway show, movie roles, and appearances on television variety shows; plus, the long-playing album, a recently introduced format, was gaining popularity, and also happened to be the perfect vehicle for his collection of Caribbean folk songs, work songs, and calypso tunes. Working with playwright and songwriter William Attaway and composer Irving Burgie (also known as Lord Burgess), Belafonte put together a set that would include two of what would become his signature songs: "Jamaica Farewell," and "Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)."

Belafonte was already no stranger to the Billboard chart; in fact, his second release, 1955's "Belafonte," was sitting comfortably in the No.1 spot when the Billboard Top 200 was inaugurated on March 24, 1956. The success of "Calypso," though, was unprecedented in myriad ways. It knocked Elvis Presley's first album from the No.1 spot, where it remained for a jaw-dropping 31 weeks; it spent a total of 58 weeks in the Top 10, and 99 weeks in the Top 100. In addition, it became the first LP by a solo artist to sell a million copies, spawned legions of imitators, and bestowed upon Belafonte a title which would follow him for the rest of his long life — the "King of Calypso."

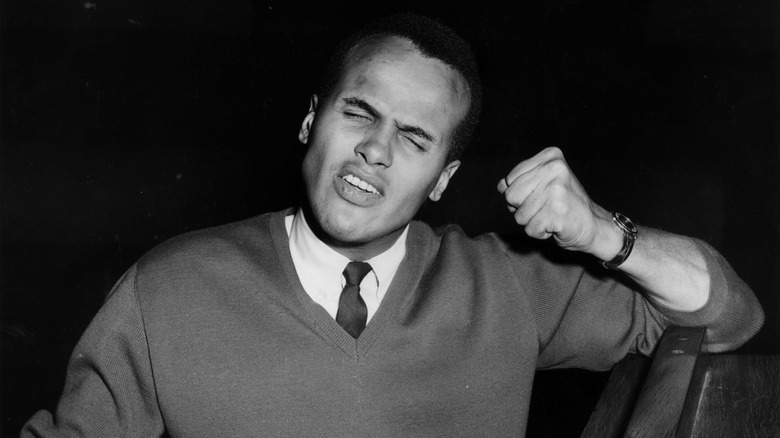

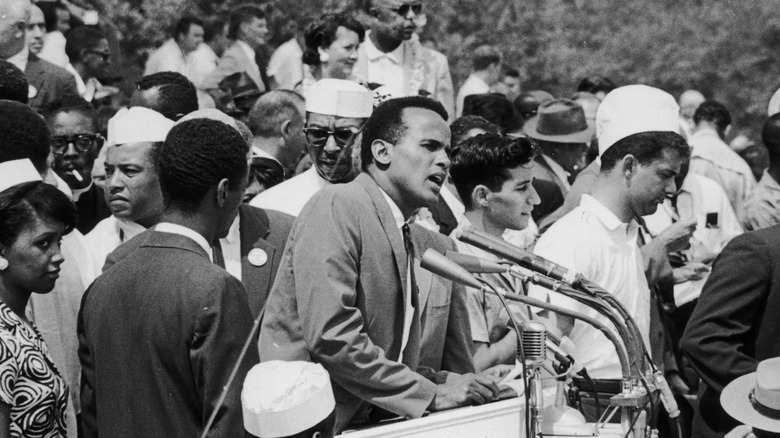

Harry Belafonte played a powerful role in the Civil Rights Movement

Harry Belafonte was committed to civil rights throughout his life and career. He was a supporter and close confidant of Martin Luther King Jr., according to the King Institute. "Whenever we got into trouble or when tragedy struck, Harry has always come to our aid, his generous heart wide open," Coretta Scott King wrote in her 2017 autobiography, "Coretta: My Life, My Love, My Legacy." According to the Sanders Institute, Belafonte paid for babysitters and housekeepers that allowed the Kings to travel on campaigns.

According to the Sanders Institute, Belafonte marched with King and coordinated events and fundraisers. When Dr. King was held in a jail cell in Birmingham, Alabama, Belafonte raised the $50,000 that allowed King's civil rights efforts to continue. Following the civil rights leader's assassination in 1968, Belafonte offered Coretta emotional support and served as an executor of King's estate and the chairman of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Fund.

Harry Belafonte was active in the anti-apartheid movement

According to the Chicago Tribune, Harry Belafonte began protesting the policies of the South African government as far back as 1959. His advocacy for Black South Africans continued for several decades. In 1965, he released the album "An Evening with Belafonte/Makeba," which dealt with themes relating to the struggles of Black South Africans under apartheid.

During the mid-1980s, Belafonte was involved in the USA for Africa supergroup, helming the highly successful "We Are the World" charity single for African famine relief. That project led to a resurgence in Belafonte's career — and his activist efforts. In 1988, he released "Paradise in Gazankulu," an album of apartheid protest songs. Around this time, he co-founded a group with tennis player Arthur Ashe called Artists and Athletes Against Apartheid. Belafonte was criticized by some for his call for artists to stop performing in South Africa during apartheid.

”To speak out against an unjust war was treasonous, to speak against the treatment of Blacks made you a Communist dupe,” Belafonte told the Chicago Tribune. ”But if you feel in your heart that you have a responsibility because of your good fortunes to advance justice and human rights, then you hang in.”

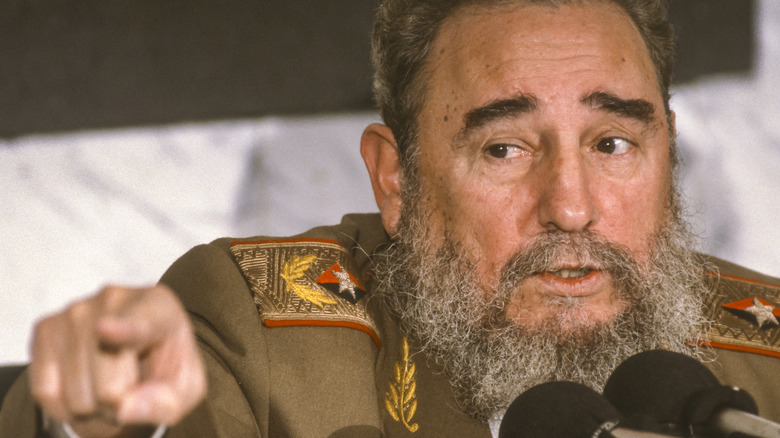

He helped to support Hip-Hop in Cuba under Castro

Henry Belafonte has long been a supporter of the Cuban people and government, which obviously is a controversial position in the United States. In his 2011 memoir "My Song," Belafonte wrote: "To me, Fidel Castro was still the brave revolutionary who'd overthrown a corrupt regime and was trying to create a socialist utopia ... I still felt the United States should forge an alliance with Cuba that benefited both countries and gave Castro enough space to make his experiment work." In a 2003 interview with Cuba Now (via AfroCubaWeb), he described a visit to the country, during which his interest in hip-hop made quite an impression on Castro.

After spending time in the hip-hop scene of Havana (and being surprised at the quality of their music and sheer numbers), he mentioned it during a luncheon with Castro and Ministery of Culture official Abel Prieto. Returning a few years later, he was greeted in an unexpected manner by the hip-hop crowd. "They thanked me profusely and I said, 'Why?'" Belafonte remembered. "And they said, 'Because, your little conversation with Fidel and the Minister of Culture on hip-hop led to there being a special division within the ministry, and we've got our own studio.'"

Belafonte went on to suggest that the lack of anything resembling a cultural ministry in the United States might have contributed to the early demonization of rap music, which of course has evolved to become the dominant form of popular music in the U.S. today.

He produced a landmark Hip-Hop movie

In addition to acting, Harry Belafonte dabbled in film production as well — and as a socially conscious Black performer, he took an interest in the burgeoning world of hip-hop culture in the early '80s. In a piece for The Foundation, hip-hop historian and author Steven Hager recalled shopping his screenplay, "The Perfect Beat," which was based on his extensive research of the culture and interviews with luminaries such as Afrika Bambaataa and Kool Herc. After it was passed on by Jane Fonda's production company, he found an interested party in Belafonte — who purchased the screenplay, then proceeded to have it extensively reworked.

At the time, Hager was disappointed in the changes, but with time, he says he came to understand Belafonte's strategy. "Now I'm older and have kids myself, I understand where Harry was coming from," he said "I think he was motivated by a strong desire to create positive role models for young black kids." The film that resulted from Belafonte's involvement: 1984's "Beat Street," now widely regarded as a landmark hip-hop film, which introduced the world at large to the likes of Grandmaster Melle Mel, Kool Moe Dee, and Doug E. Fresh, among others.

The movie was not a box office success, but found its audience on home video; it can be seen as heralding the Golden Age of Rap Music, a form which Belafonte continued to champion in later years.

The hit charity single We Are the World began with Belafonte

On the night of January 30, 1985, directly after the American Music Awards ceremony in Los Angeles, all of the biggest pop stars in America (minus a couple notable names) converged at A&M Studios to participate in the biggest joint recording in pop music history: "We Are the World," a charity single for African famine relief. The tune, penned mainly by Lionel Richie and Michael Jackson, featured 21 soloists and a massive chorus, among whom were the likes of Richie and Jackson, Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, Ray Charles, Paul Simon, Stevie Wonder, and many others. It was a massive undertaking, to say the least, and while much of the legwork of assembling the musicians and organizing the recording fell to manager Ken Kragen, the project was the brainchild of Harry Belafonte.

Belafonte had seen the same BBC report on the famine that had inspired Bob Geldof to organize the British charity single "Do They Know It's Christmas," and he had called Kragen with the idea to organize a charity concert. In Kragen's estimation, this was not feasible — but he thought, perhaps, that they could pull off a song, and indeed they did. Belafonte was present at the recording of the tune that would go on to sell an estimated 20 million copies to become the best-selling physical single of all time at that point and raise millions of dollars to feed the hungry in Africa — and at the recording's conclusion, a room full of megastars broke into a chorus of "Day-O" in tribute.

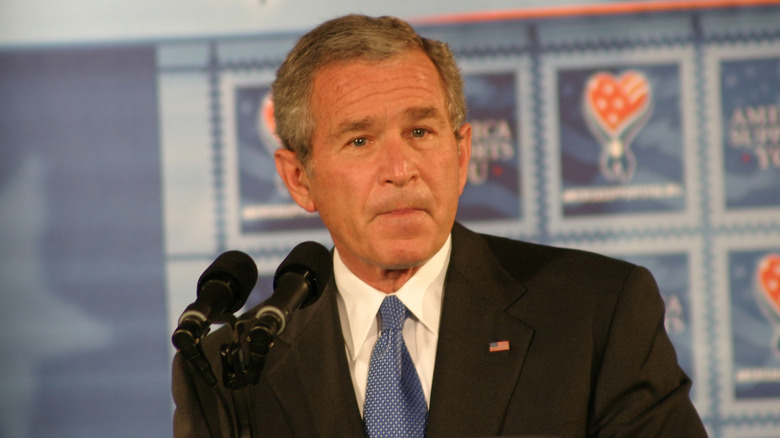

He had harsh words for the George W. Bush administration

Harry Belafonte was not one to be shy with his political opinions, and he was perhaps never more outspoken than when criticizing the presidential administration of George W. Bush. In 2002, as the administration geared up to invade Iraq in the aftermath of 9/11, Belafonte gave an interview to a San Diego radio station (via CNN) in which he said of Bush's Secretary of State, Colin Powell, "In the days of slavery, there were those slaves who lived on the plantation and there were those slaves that lived in the house. You got the privilege of living in the house if you served the master." That is one heck of a pointed analogy, but speaking with Democracy Now! in 2006, Belafonte went even further.

"I call President Bush a terrorist," he said. "I call those around him terrorists, as well." He went on to clarify that he was decrying not just the "collateral damage" of Iraqi civilians killed during the Iraq War, but the administration's domestic policies, saying, "Poverty is terror. Having your Social Security threatened is terror ... watching drugs permeate our communities and destroy our young, it's a life of terror." Later that year, in a speech at the University of Tennessee, he accused Bush of stealing the 2000 presidential election before asking rhetorically, "How do you define someone ... who lies to the citizens of the nation ... and then sends off our sons and daughters to die in a battlefield of a war that's unjust?" (via The Daily Beacon).

He had even harsher words for the Trump administration

As one might imagine, Harry Belafonte was not exactly fond of Donald Trump during his presidency. By the time Trump took power, Belafonte was in declining health and was no longer physically able to make frequent public appearances. Nevertheless, in 2017 — at the age of 90 — the icon took the stage at Carnegie Music Hall to address a rapt crowd for nearly two hours on a wealth of topics. Among those was his deep mistrust of Trump. "The country made a mistake" in electing Trump, he said, "and I think the next mistake might very well be the gas chamber, and what happened to Jews [under] Hitler is not too far from our door" (via The Guardian).

Three years later, as Trump was running for re-election, Belafonte penned an essay in The New York Times urging Americans, and Black Americans in particular, not to make the same mistake twice. He asserted that on Trump's watch, Black Americans had lost "our lives, as we died in disproportionate numbers from the pandemic he has let flourish among us. Our wealth, as we have suffered disproportionately from the worst economic drop America has seen in 90 years. Our safety, as this president has stood behind those police who kill us in the streets." He ended the essay, however, on an optimistic note, saying that "the wheel is turning again ... we have never had so many white allies, willing to stand together for freedom, for honor, for a justice that will free us all in the end."

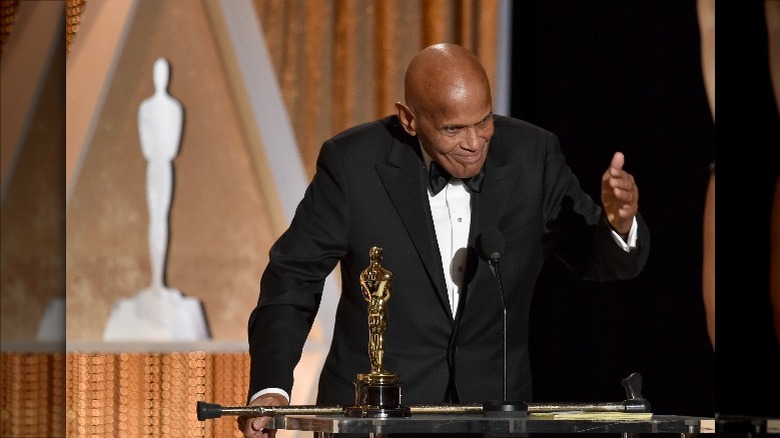

He is an EGOT winner

Over the course of his career, Henry Belafonte became one of the select few performers to earn the illustrious EGOT designation — those who have won at least one Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony Award. He began his collection in 1954, with a Tony win for the Broadway production "John Murray Anderson's Almanac," which he composed the music for and starred in. In 1960, he collected an Emmy for his appearance on the CBS variety show "The Revlon Revue," becoming the first Black person to win that particular award. At the time, The Hollywood Reporter praised the outing as having "several choice high spots, the likes of which are seldom seen on TV, delightfully staged." Speaking with that outlet over six decades later in 2021, Belafonte said, "Sixty-one years ago — it is hard to remember specifics of an evening. I am glad to have broken a barrier and so many since."

Belafonte was also nominated for 11 Grammy Awards and took home two, for 1960's "Swing Dat Hammer" and 1965's "An Evening with Belafonte/Makeba" (a collaboration with legendary South African singer/songwriter Miriam Makeba, also known as "Mama Afrika"). Finally, in 2014, he won the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award Oscar, an honorary award given to an "individual in the motion picture industry whose humanitarian efforts have brought credit to the industry." One could make the case that this award was a touch belated, but better late than never — and in collecting it, Belafonte completed perhaps the most prestigious accomplishment in the world of entertainment.

He's a Rock and Roll Hall of Famer

Harry Belafonte has never made a recording that would come within shouting distance of being classified as rock 'n roll, but that didn't stop him from being inducted into the Rock Hall of Fame in the Early Influences category in 2022 — and that induction was for good reason. Aside from paving the way for a generation of Black performers to achieve massive pop success, sell-out concert tours, and become household names, Belafonte carried the spirit of rock 'n roll with him in his intense, lifelong commitment to activism — a spirit that would rub off on countless musicians that followed him.

On the occasion of his induction, blues singer and songwriter Reverend Shawn Amos penned a heartfelt tribute to Belafonte, which can be read on the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame's website. In it, he opined, "Harry Belafonte is not a rock & roll singer. He never was a rock star ... But Harry Belafonte is unmistakably rock & roll." He went on to point out that virtually every musician to express a political point of view through their music stands on Belafonte's shoulders, name-checking "Bob Marley, Bob Dylan, Bono, the Clash, Marvin Gaye, John Lennon, Rage Against the Machine, [and] Public Enemy." Indeed, there are several Rock Hall inductees on that short list, and Amos praised Belafonte for "[delivering] the anger and agitation that – at its best – are what rock & roll promises."

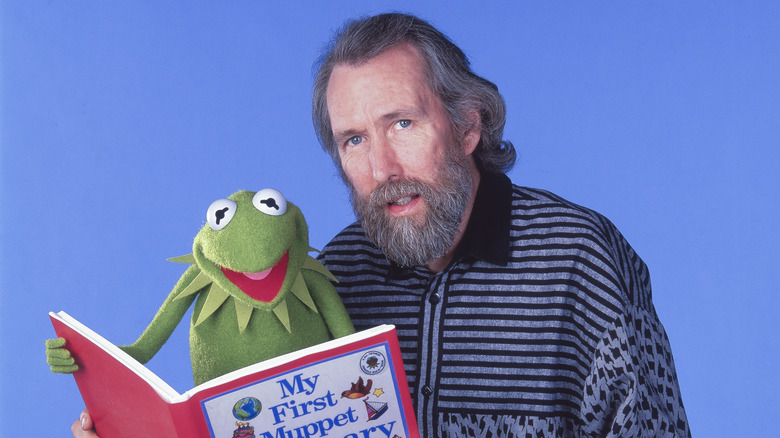

One of his greatest performances came on an unlikely TV show

Harry Belafonte's life and career were full of poignant performances, delivered with passion and verve. But among his very greatest performances, one came via a very unlikely venue: "The Muppet Show," on which Belafonte guested in 1978. Belafonte, of course, performed "Day-O," took part in an episode of the classic sketch "Pigs in Space," and participated in a drum battle with Animal — but to close the show, he performed the title track from his 1977 LP "Turn the World Around," an uptempo number with a theme of interconnectedness featuring Muppets wearing African tribal masks.

The creator of the Muppets, Jim Henson regarded the episode to be among the very best the series had ever produced, and Belafonte also held Henson in high regard. When Henson passed away in 1990, Belafonte was present at his funeral, where he eulogized the legendary puppeteer. "There is no question about Jim Henson's great artistry, and the extent to which we have all been touched by it," he said. "But even greater than his artistry was his humanity ... [Many have been] touched in a profound way because Jim Henson said, 'There is hope. There is joy. There is the ability to love and to care, and to find greatness in difference' ... That is the legacy that I think we carry with us." After wrapping up his remarks, Belafonte closed with a rendition of "Turn the World Around" in tribute to his friend.