The Untold Truth Of Bob Marley

With the possible exception of the late, great Calypso King Harry Belafonte, no musical artist has ever embodied their genre quite like the also late, equally great Bob Marley. He didn't single-handedly invent reggae, but he was certainly right in the middle of its inception — and absolutely nobody did more to lift the genre from a phenomenon on the streets of Kingston to permanent residence in clubs, dancehalls, and living rooms worldwide. For much of his life, Marley was a devout Rastafarian — but he embraced reggae like a religion, and millions of fans followed him as fervently as they would any religious leader.

Marley may have only lived to the age of 36, but he lived a full life dedicated to the cause of spreading peace, love, and unity as far and wide as he possibly could. Decades after his death, his 1984 greatest hits collection, "Legend," continues to sell around a quarter-million copies per year, and every cut on the album justifies its title — iconic tracks like "Buffalo Soldier," "Get Up, Stand Up," and signature tune "One Love," all of which are the very definition of timeless. The latter song lent its title to the 2024 biopic "Bob Marley: One Love," starring Kingsley Ben-Adir, which is an excellent exploration of Marley's life and legacy — but here are a few things you may not have known about one of the most important artists of our time.

Bob Marley's parentage was unique

Robert Nesta Marley was born on February 6, 1945, to parents who were an unusual pair, especially for the time. His mother, Cedella Booker, was an 18-year-old native Jamaican; his father, Norval Marley, was a 60-year-old white Briton who was working as a supervisor on a Jamaican plantation. The two were together for only a short time, going their separate ways shortly after their son arrived into the world, and Norval Marley passed away when Bob was only 10 years old. Not that he had had much of a presence in his son's life anyway; Bob Marley rarely spoke about his father, and when he did, it was usually with a fair amount of venom.

Little is known about Norval Marley other than that he served in World War I, but not in a combat capacity. Although he was fit, his war record revealed that he was incontinent, and after undergoing an operation for an undisclosed medical issue, he spent the entire war in a support role in the U.K. Marley's mother would at times say that Norval Marley had been a captain in the army, but actress Esther Anderson, who was Bob Marley's girlfriend for a time in the '70s, told the BBC that most of her stories were embellished or outright false. As for Bob Marley, his father could hardly have had less of an influence. "The guy didn't exist," Anderson said. "[Marley had one] photograph of him on a horse, a white man on a horse."

Bob Marley grew up in poverty as a street fighter

Bob Marley grew up in the mountain community of Nine Miles in St. Ann Parish, Jamaica, striking out for Kingston as a young man. Fans of his music know that he often references Trenchtown, the Kingston settlement in which he came of age — but even they may be appalled to learn how it came by its name. The settlement was comprised of low-income government developments and burned-out squatter residences, and it earned its name by virtue of being built on top of a literal sewage trench. As one might imagine, the area was home to a goodly number of street toughs, known as "rude boys" — and while Marley didn't put himself in this category, he wasn't afraid to throw down with them.

According to Marley's website, it was because of his skills as a street pugilist that he came by a nickname that would stick with him for pretty much his entire life: "Tuff Gong." This is, of course, the name of the record label he would eventually found, one which would become a driving force in spreading reggae music to an international audience. Perhaps the most well-known nod to this time of Marley's life in his music came in his classic 1974 tune "No Woman, No Cry," in which he sang, "I remember when we used to sit / In the government yard in Trenchtown / Observing the hypocrites / Mingle with the good people we meet."

An unfortunate welding accident gave us his music career

Like many Kingston youths, Bob Marley showed an early interest in becoming a part of the local music scene; in the early '60s, he was dabbling in writing songs with a childhood friend, Neville Livingston. Marley's mother Cedella, though, knew this was no certain path out of poverty — and when Marley dropped out of school at the age of 14, she tried to make sure he would have a trade to fall back on. Cedella found Marley an open apprenticeship as a welder, and although he wasn't exactly thrilled about it, Marley accepted.

It wasn't long, though, before Marley decided he was not to be a welder. The decision came courtesy of a scalding hot piece of metal that flew into his eye while he was in the shop one day. So painful was the incident that this became Marley's last day as an apprentice welder, and after leaving the shop he resolved to dedicate himself to music. Aside from setting him on the path that would make him a legend, his time as a welder's apprentice yielded one other benefit: a friendship with a fellow welder by the name of Peter Tosh, who also harbored musical ambitions, and who would prove to be a capable songwriter in his own right. Tosh, Marley, and Livingston — who would soon become known as Bunny Wailer — promptly formed their own vocal group, but they would need a bit of guidance before they were ready for the world.

Bob Marley was tutored by the Godfather of Reggae

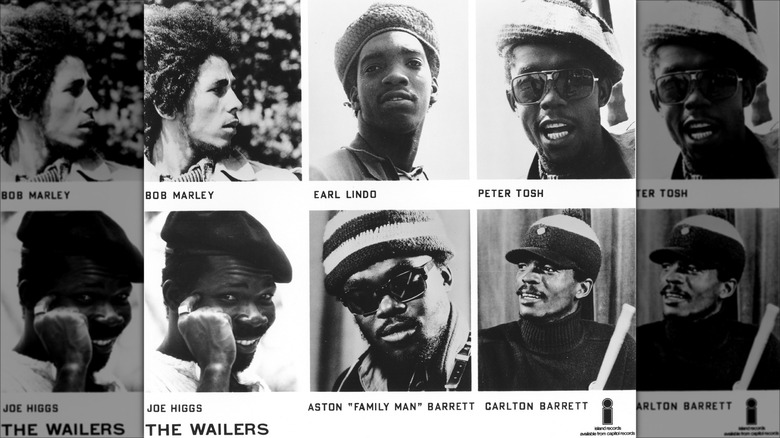

In the early '60s, Kingston's music scene was a bubbling melting pot of influences — and there was no more prominent figure in that scene than Joe Higgs, who was part of a singing duo with fellow Trenchtown resident Delroy Wilson. A singer, songwriter, and guitarist, Higgs sang in a gutsy, straightforward style unlike many of his peers; also unlike them, he took a great interest in cultivating the talents of the many budding musicians who were jostling for space in Kingston's clubs and dancehalls. Higgs was known to tutor pretty much anyone who showed up on his doorstep in the basics of singing and songwriting, for free — and Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, and Bunny Wailer were by far his most successful students.

As a successful musician himself, Higgs imparted his mentees with the type of knowledge that could give them some polish — such as the concept of breath control, how to compose melodies on guitar, and how to write meaningful lyrics. (Higgs described himself as, more than anything else, a protest singer.) When Marley and the Wailers began to experience success, Higgs refused to ride their coattails, staying largely in the background — although, when the band underwent some lineup changes in the early '70s, he did join them on a tour of the U.S., and co-wrote the tune "Stepping Razor," which would become a solo hit for Tosh. Higgs passed away in 1999, but he is remembered, alongside Marley, as one of the greatest artists Jamaica has ever produced.

Bob Marley was cheated by his first producer

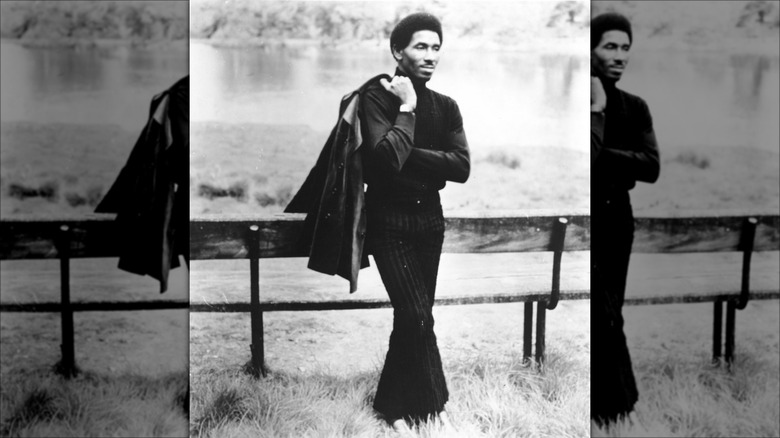

Chinese-Jamaican businessman Leslie Kong, who owned a restaurant and record store called Beverley's in Kingston in the early '60s, fell into being a record producer quite by chance. One day, a teenager calling himself Jimmy Cliff (pictured above) wandered into Kong's store; an aspiring singer, Cliff figured he needed a successful businessman to fund his recording endeavors. Kong was impressed, and just like that, a partnership was born, and Cliff's recording career — which bore immediate fruit in the form of hit singles like "Hurricane Hattie" and "Miss Jamaica" — was off to the races. Before long, Cliff was acting in an A&R capacity for Kong's fledgling record label — and in that capacity, he introduced Kong to Bob Marley, who made his first recordings for the budding mogul.

Unfortunately, Kong shamelessly underpaid Marley for those recordings, shelling out only a paltry $20 to the singer. Nevertheless, the Wailers continued to record several tunes for Kong, as his shady business practices were pretty much par for the course in Jamaica at the time. In 1970, though, Kong made a business decision which, if you hold certain rather esoteric beliefs, may have cost him his life. Without the band's permission, he announced his intention to issue a compilation, "Best of the Wailers," that year, drawing the extreme ire of Bunny Wailer — who, according to legend, placed a death curse on Kong if he were to follow through. He did — and just a year after the album's release, Kong died of a heart attack at just 37 years old.

Bob Marley's first successful single was meant to allay his mother's fears

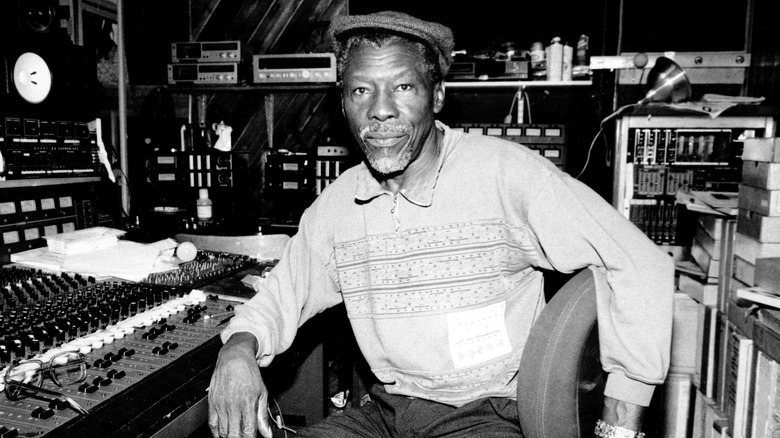

Before long, Bob Marley and the Wailers found themselves another producer, and what a producer he was: Clement "Sir Coxsone" Dodd (pictured), proprietor of Studio One, in which virtually all of the legends of reggae cut their formative recordings. For that matter, the genre itself — not to mention the genres of ska, rocksteady, and dancehall — were arguably formed at his mixing board, and with his guidance, the Wailers shaped themselves into a crack unit that scored a slew of hit singles, including several No. 1 hits in Jamaica.

The first of those successful tunes was titled "Simmer Down," and as the title implies, it was an exhortation to the "rude boys" of the Kingston slums to settle their scores non-violently; on it, Marley sang, "Oh, control your temper / Or the battle will be hotter / And you won't get no supper / And you know you're bound to suffer." It was an admirable message, but the tune served a purpose for Marley that was distinctly, and humorously, personal: his mother, Cedella, had long been worried about her son's potential association with the rough and rugged street toughs of Trenchtown, and "Simmer Down" was Marley's way of demonstrating to his mother that he felt no kinship with them.

Bob Marley has a connection to the state of Delaware

The timeline is a bit murky, bu it is known that some time after the death of Bob Marley's father, his mother Cedella remarried and moved to Delaware. According to Marley's website, this happened in 1966 (although some sources cite an earlier, or later, time for her relocation), which was the year Marley married his wife, Rita, to whom he remained married until his death. At some point, the Marleys joined Cedella in Delaware; some sources say for a matter of months, others for several years. Few of his neighbors knew that Marley was semi-famous in his home country — least of all Ibis and Genny Pitts, who befriended the couple after Rita happened to visit their gift shop.

Ibis Pitts, a drummer, used to jam with Marley, and became enamored of a Wailers 7-inch gifted to him by Rita. Pitts shared with Delaware Online that when Marley's visa expired, he even accompanied him to Jamaica, where he was dumbfounded by the throng comprised of fans, footballers, and Wailers who followed Marley around. ("It was like Jesus with his disciples," he said.) In 1984, years after Marley's death, the Pitts family organized a music festival in his honor — the People's Festival for Peace — which still takes place in Wilmington, Delaware, to this day.

Bob Marley was a relatively late convert to Rastafarianism

Bob Marley was living in Delaware when an important milestone in Jamaican history occurred: Grounation Day, April 21, 1966, which is still celebrated by faithful Rastafari today. On that day, Haile Selassie, the Emperor of Ethiopia, visited the island for the first time, touching off a frenzy among the populace. By way of brief explanation for the uninitiated, Rastafarianism began in the early 20th century in Jamaica; it draws from a number of religious and political belief systems, but put simply, its adherents believe Africans displaced by the slave trade to be exiles in the corrupted outside world (known as "Babylon"), and await their eventual return to Africa (or "Zion") in accordance with their interpretation of the New Testament's Book of Revelation. At that time a seat of power in Africa, Ethiopia was believed to be a holy land — and its emperor, Selassie, to be the literal second coming of Christ.

It was Selassie's visit to Jamaica that prompted Marley to begin examining his spirituality, eventually becoming a convert to Rastafarianism (and growing out his trademark dreadlocks). By this time, he was already in his early twenties — but his religious conversion would, of course, have a profound impact on the remainder of his life, to say nothing of his music. When Marley returned to Jamaica to reform the Wailers in the late '60s, the band had a new direction — but a few more difficult years lay ahead.

A reggae legend allegedly cheated the Wailers out of royalties

The importance of the legendary Lee "Scratch" Perry to the career of Bob Marley and the Wailers is well documented; he produced their album "Soul Rebels," their first LP to be released outside of Jamaica, and he helped them to achieve their signature sound by hooking them up with the rhythm section that set a new standard not just for the Wailers, but for all of reggae music: drummer Carlton Barrett and his brother, bassist Aston "Family Man" Barrett. The record certainly gained the band more recognition — but it didn't exactly line their pockets, and if Bunny Wailer is to be believed, that was because Perry was lining his own.

Speaking with Rolling Stone in 2010, Wailer was blunt in his assessment of the relationship. "Lee Perry did nothing for the Wailers. He just sat there in the studio while we played our music, and then he screwed us," he said. "We never saw a dime from those albums we did with him. Records that other people have made millions from ... I never forgave him." Perry, of course, remembered it differently, telling Afropop Worldwide in 2017 that Wailer was just bitter and holding a grudge against him for unspecified reasons. But Marley and the Wailers made their feelings known as a matter of record, literally; Rolling Stone noted that the 1973 tune "Trenchtown Rock" was referencing Perry in its lyrics, "You reap what you sow / And everyone know now / Don't turn your back."

Another difficult relationship with soul legend Johnny Nash ended poorly

Another in a long line of what could have been big breaks for Marley came when, while playing guitar at a party in Kingston, he was corralled by a pair of Americans: manager Danny Sims and his client, soul singer Johnny Nash. They had been trying to inject a little island flavor into Nash's newest tunes, and feeling that Marley could help, they proposed a partnership: Marley and the Wailers would come to London to help Nash write some new songs, and in return, the band would open some shows for Nash and receive consideration for a possible contract with his label, CBS Records.

It all sounded great — but it worked out a little better for Nash than it did for Marley and the Wailers. Nash recorded a few of Marley's tunes (including the future classic "Stir It Up"), and got one original song out of the endeavor — the 1972 reggae-flavored No. 1 hit "I Can See Clearly Now" — that is nothing short of immortal. But Marley soon became disillusioned with the whole thing; in his book "Before the Legend: The Rise of Bob Marley," author Christopher Farley quoted him as saying, "He's a nice guy, but he doesn't know what reggae is. Johnny Nash is not Rasta; and if you're not a Rasta, you don't know nothing about reggae" (via Santa Monica Daily Press). When CBS Records insisted the Wailers record the borderline-novelty song "Reggae on Broadway" and then did nothing to promote it, the band terminated the relationship.

Bob Marley may never have gained fame if not for one rogue executive

After things went south for Bob Marley and the Wailers in London, they needed a way to get home to Jamaica — but what they found instead was nothing less than their ticket to worldwide stardom. In his memoir "Islander: My Life in Music and Beyond," Island Records founder Chris Blackwell described his first meeting with the group, who showed up out of the blue one day at his office (via Rolling Stone). Island had distributed a few of the Wailers' records in the U.K. (along with a raft of other Jamaican artists), and "Bunny [Wailer] had it in his head that I owed them some money," Blackwell wrote. "They did not walk in like losers, like they were defeated by being flat broke. To the contrary, they exuded power and self-possession."

As it turned out, Jimmy Cliff had just departed Island, and although U.S. radio stations were steering clear of reggae, Blackwell "knew [he] could do something" with the Wailers — "move them away from where they were and make their music attractive to college kids." By the end of their conversation, Blackwell had agreed to pony up 4,000 pounds for the band to make an album — without even having them sign a contract. A couple months later, he went down to Jamaica to hear what they'd done — and was blown away by the rough tracks that would become "Catch a Fire," Bob Marley and the Wailers' classic breakthrough album.

Bob Marley was nearly killed over his attempt to unite Jamaica's political movements

As Bob Marley's religious and cultural interests grew, so too did his interest in Jamaican politics — which, in the '70s, were beyond contentious. This may sound a touch familiar: At the time, the nation's populace were bitterly divided between the liberal People's National Party (PNP) and the conservative Jamaica Labour Party (JLP), and those divisions often boiled over into violence. In an attempt to unite his countrymen, Marley agreed to play a free, non-partisan concert called "Smile Jamaica" on December 5, 1976 — one that was nearly derailed by the very political violence it sought to quell.

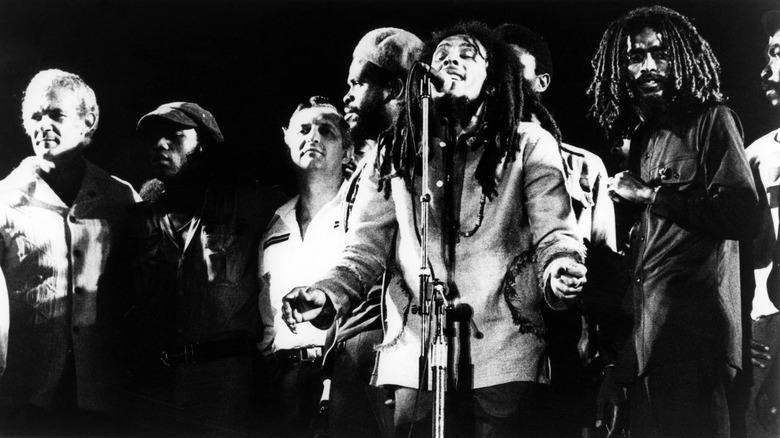

On December 3, the Wailers were rehearsing at Marley's Kingston home when the house was riddled with bullets from numerous unknown assailants. Marley was shot in the arm, Rita Marley's head was grazed, and the band's manager, Don Taylor, was shot five times, but survived. Undaunted, Marley performed at the concert two days later, the bullet still lodged in his arm — and if anything, Marley's resolve to help bring about unity grew even stronger. Two years later, he participated in a similar concert, this one known as the One Love Peace Concert, at which Jamaican PNP Prime Minister Michael Manley and JLP leader Edward Seaga were both in attendance. Marley called them onstage and basically forced them to shake hands. Just weeks later, in recognition of this daring effort, the United Nations awarded Marley its Medal of Peace.

A young Kurtis Blow was starstruck by Bob Marley

Bob Marley and the Wailers' final tour of the United States was an unmitigated triumph; the band played back-to-back nights at New York's legendary Madison Square Garden with Lionel Richie's Commodores, one of the biggest bands in the country at the time. Also on the bill, opening for both acts: a young MC named Kurtis Blow, the first rapper to sign to a major label, and arguably rap's first major star. Young as he was, Blow was still humble enough to be completely starstruck by Marley when the pair ran into each other backstage.

Speaking with Ice-T's Final Level podcast, Blow remembered that he had played a ton of dates supporting the Commodores on their U.S. tour when Marley joined the bill for their New York dates at the suggestion of the promoter. "[The promoter said], 'There's a guy, you might not know who he is, but [I'll] tell you right now, you put him on the show, you're gonna sell out,'" he said. "'He's a reggae guy; his name is Bob Marley.' They put Bob Marley on the end of the show, [and] we sold out. In just like, five minutes, boom — sold out." Backstage, Marley and his entourage happened across the young rapper. "Bob Marley comes straight up to me, sticks out his hand and goes, 'Kurtis, I like your stuff,'" he remembered. "I'm always starstruck when O.G.'s in the game recognize me."

Bob Marley's religious beliefs may have cost him his life

Bob Marley's altruism and drive to make the world a better place made the Rastafarian religion a perfect fit for him, but unfortunately, one aspect of that religion discouraged him from getting the medical care that could have saved his life. When the cancer that would eventually kill him first appeared under his toenail in the late '70s, it was mistaken for a simple sports injury; Marley was an avid footballer (or soccer player, for us yanks), and such injuries were not uncommon. When he was diagnosed with melanoma, though, Marley's doctors told him that the best course of action was to have the toe amputated — which was against the singer's religious beliefs.

Marley did agree to a skin graft, but that was not enough. By the time it was discovered, shortly after those legendary Madison Square Garden dates, that the cancer had spread throughout his body, aggressive medical treatment was needed — but Marley chose to also forgo that, in favor of alternative treatments consisting mostly of dietary changes, which he undertook under the care of a German doctor. After eight months with no success, Marley was on his way home to Jamaica when his condition became critical in-flight; he was hospitalized in Miami, where he died on May 11, 1981.

Bob Marley was almost reburied in Ethiopia

In a mirror image of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie's visit to Jamaica, which had so inspired Bob Marley as a young man, the musician paid a visit to Ethiopia in 1978. While there, he stayed in Shashamane, a town that had been designated by Emperor Selassie himself as a settlement for Rastafari; he performed for Ethiopia's royal family, visited churches, and did a bit of writing, working on some songs that would later appear on the Wailers' 1979 album "Survival."

All these years later, there are still a few hundred Rastas living in Shashamane, and in 2015, the icon's fondness for the Rasta "homeland" was returned with a statue of him, which was erected in the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa. A decade prior, Rita Marley had announced her intention to rebury her husband in Ethiopia, saying, "Bob's whole life is about Africa, it is not about Jamaica ... He has a right for his remains to be where he would love them to be. This was his mission. Ethiopia is his spiritual resting place." Understandably, this ruffled a few feathers in Jamaica, where Marley is obviously considered to be a national treasure. Said Marley historian Roger Steffens at the time, "Bob never expressed any interest to be buried in Ethiopia. The country that created the faith of Rastafari is Jamaica, not Ethiopia" (via The Guardian). The reburial never came to pass.

A music legend paid tribute to Bob Marley in song

In 1975, Bob Marley and the Wailers staged a concert in Kingston, dubbed the "Wonder Dream" concert, to benefit the Jamaican Institute for the Blind. There was a thrilling reason for the show's moniker: One of the most prominent blind musicians in history, Stevie Wonder, was in attendance and ready to jam. He and the Wailers took the stage together at one point, performing the band's "I Shot the Sheriff" and Wonder's "Superstition," and the show led to a friendship between Marley and Wonder that would endure for the rest of the former's life. They performed together again at a 1979 Philadelphia show, and even kicked around the idea of staging a joint concert.

On September 20, 1980 — one day before Marley collapsed while jogging in New York's Central Park, leading to the discovery that his cancer had metastasized — Stevie Wonder's single "Master Blaster" debuted on the Billboard chart, where it was destined to peak at No. 5. The reggae-flavored tune was a tribute to Wonder's friend, featuring lyrics such as, "Marley's hot on the box / Tonight there will be a party" and "Didn't know you / Would be jammin' until the break of dawn." Wonder would go on to write and produce for reggae act Third World, with whom he performed "Master Blaster" at the Reggae Sunsplash festival in 1982.

The Bob Marley Foundation continues his life's work

Bob Marley has been gone for more than four decades, but his spirit lives on, and not just through his music. In 1986, Rita Marley founded the Bob Marley Foundation in his honor, a non-profit organization that, as described on its official website, was created "to perpetuate the spiritual, cultural, social and musical ideals and goals which guided and inspired [Marley] during his lifetime." To that end, the Foundation has done some incredible work, making a tangible difference in the lives of thousands of Jamaicans over the years.

The Foundation has provided university scholarships for hundreds of students, not to mention funding for primary schools throughout the country. This funding has paid for books, school supplies, and — critically — tablets that were needed for remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. It has provided hospitals and clinics with modern equipment, established a fund for residential care for the elderly, sponsored the Jamaica National Women's Football Team, and — of course — lent its support to cultural endeavors such as film festivals, art exhibits, and music workshops. It also established the One Love Youth Camp, which steers at-risk youth away from the streets and toward the welcoming embrace of music and art. In describing the Foundation's mission, the website places a quote from Marley himself front and center: "My life no important to me," it reads, "but other people life important. My life only important if me can help plenty of people."