The Untold Truth Of Rastafari

The religion of Rastafari, or Rastafarianism, is one of the newer mainstream organized religions; it was started in the 1930s in the Caribbean country of Jamaica (via Britannica). Followers of the religion call themselves Rastas and are often recognizable by their distinctive dreadlock hairstyle. As Rastas started to emigrate away from their home country, many of them took their religious traditions with them, spreading their beliefs to their new communities far outside of Jamaica (per History).

Rastafarianism rose to mainstream prominence through reggae music, and most famously from Jamaican artist Bob Marley and his band the Wailers. It is a mostly decentralized religion, without a main church, and most Rastas worship independently and in their own ways. They generally believe that people who were forcibly removed from Africa during the slave trade are "exiles in Babylon [the New World]" outside of Africa, and they "await their deliverance from captivity and their return to Zion [Africa]" (per Britannica). In 2012, it was estimated there were 1 million Rastas worldwide. Their beliefs and heritage are often marginalized and appropriated for commercial uses, especially with respect to cannabis, but Rastafarianism has rich cultural traditions that are highly important to Rastas. This is the untold truth of Rastafari.

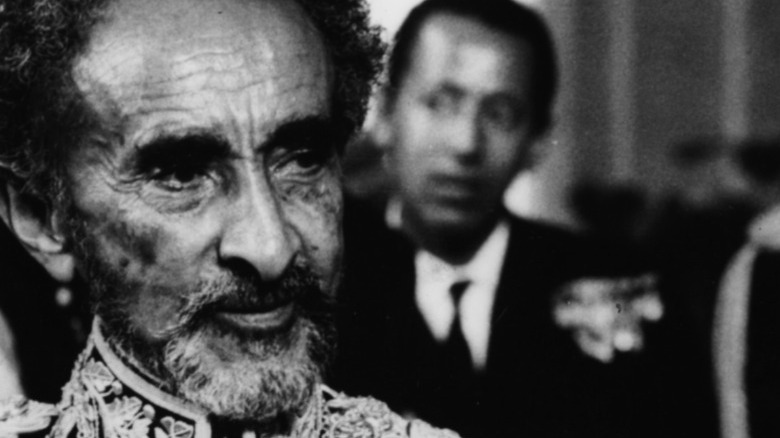

Rastafarianism is named after an Ethiopian king

While Rastafarianism was founded and established in Jamaica, it actually revolves around a former Ethiopian king, Emperor Haile Selassie. Selassie was crowned in November 1930, and he took the title "His Imperial Majesty, Emperor Haile Selassie I, King of Kings, Lord of Lords, and Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah" (via Smithsonian Education). This was a high-profile event internationally and drew press from many different countries, which was a unique phenomenon for Africa at the time.

The significance for Rastafarianism comes in how the Rastas interpreted this coronation. According to Leonard E. Barrett in "The Rastafarians: Sounds of Cultural Dissonance," the title "Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah" signified that Selassie traced his lineage to the ancient Jewish King Solomon. This made the affair not just a secular event for Rastas, but brought added biblical implications of a new religious king being crowned. In addition, a statement from Rastafari progenitor Marcus Garvey claiming "Look to Africa for the crowning of a Black King; he shall be the Redeemer," was also influential for Rastas.

They saw Selassie as fulfilling both Garvey's and biblical prophecies and considered him to be their "Messiah of African redemption." In addition, Selassie's name before he became king was Ras Tafari, which is where the name Rastafari comes from. It is unclear exactly why the name Rastafari was chosen over Haile Selassie, but the latter is still used in prayers, and many Rastas refer to him as Jah (God).

Rastafarianism is based on the Old and New Testaments

Though Rastafarianism is based on the idea of a new African messiah in the form of Haile Selassie and not Jesus Christ, the scriptural basis for the religion is actually the Judeo-Christian Old and New Testaments. There are scriptures in the Book of Revelation from the New Testament that use the terms "Lion of the tribe of Judah" and "King of Kings, Lord of Lords," both of which Emperor Haile Selassie took as part of his name upon his coronation (per Leonard E. Barrett in "The Rastafarians: Sounds of Cultural Dissonance"). This had special significance for Rastas, who believed that the new African king was fulfilling biblical prophecies through his lineage and coronation.

In addition, Rastas also point to the Book of Daniel in the Old Testament, which they believe prophesied that a black Ethiopian king will have a long and fortuitous reign. However, Rastas are not fond of the King James Bible, or many Christian versions of the Bible, which were originally used to convert their enslaved ancestors to Christianity. They believe that the King James Bible is a corrupted version of the word of God that was used to control African people through mental and physical slavery (per Britannica). They read selective parts of the Bible, emphasizing their forced "exile in Babylon," or Western society. For many Rastas, returning to their ancestral lands in Zion (Africa) is the goal of their movement.

The Mansions of Rastafari

Rastafari is a highly diverse religion with many followers in Jamaica, and the different denominations are known as the "Mansions of Rastafari." The main mansions are the House of Nyabinghi, the Bobo Shanti (or Bobo Dread), and the Twelve Tribes of Israel -– though there are several other smaller houses or mansions of Rasta (per Ennis Barrington Edmonds in "Rastafari: A Very Short Introduction").

The House of Nyabinghi was developed in the 1940s among militant Rastas, and they are a highly patriarchal sect, though they take their name from an ancient African queen. The Bobo Shanti originated in the 1950s and are connected with the Ethiopia Africa Black International Congress and Prince Emmanuel I –- a Rasta king. They have developed a frugal lifestyle, derived from subsistence farming, and they make and sell brooms for a living. The Shanti are also highly patriarchal and see "women as distracting to men's spiritual pursuit;" they view Marcus Garvey as a prophet, Selassie as the God-King, and Emmanuel and the high priest (per Edmonds).

The Twelve Tribes house was founded in the late 1960s by a Rasta prophet, who claimed to be the reincarnation of Gad, a son of Jacob and founder of one of the ancient Twelve Tribes of Israel. Twelve Tribes followers believe that Jesus Christ was the messiah –- unlike most Rastas. They are at times referred to as "Christian Rastas" because of this.

Rastas grow dreadlocks as a form of rebellion

For Rastas, the dreadlock hairstyle is more than just an aesthetic choice; it has deep cultural and spiritual significance within the Rastafari religion. According to oral Rastafari tradition, the modern trend of dreadlocks is inspired by the looks of African tribesmen and Hindu holy men (per Ennis Barrington Edmonds in "Rastafari"). It also has biblical connotations, as Rastas cite the books of Numbers and Judges as their justifications for long hair and unshaven beards.

The dreadlock hairstyle is also seen as a form of rebellion against European and Babylonian cultures. Edmonds writes that Rastas eschew the finely articulated beauty standards of Europe, and purposefully contrast them with their "nappy" and knotted dreadlocks. They emphasize the naturalness of their hair over the use of artificial chemicals and processes. Rastas see other Black people who use hot combs and try to straighten their hair as "the approximation of whiteness," and find it contradictory to the teachings of Jah.

Dreadlocks are also symbolic of a lion's mane, and the lion is indeed a motif in Rastafari that, according to Edmonds, is "intended to expunge the stereotypically weak, fickle personality that oppressive systems in the Americas have foisted upon Blacks." The lion motif also connects followers with the Rasta King, whose title has "Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah" in it, and who used the lion as a symbol in several other respects.

Rastafarians have their own language known as dreadtalk

In the 1940s, a new type of language started to emerge from the Rasta culture known as dreadtalk. Rastas found both English and the Jamaican language known as patwa unable to express the complex feelings and attitudes of Rastafari, and they created a new vocabulary that was a creole of both languages (via Ennis Barrington Edmonds in "Rastafari"). One common trait in dreadtalk is the prominence of "I" words, like inity, irator, or iration, which are derived from English words like unity, creator, and creation, but are scrubbed of the Babylonian (Western) influence. They also have other words that emphasize the letter I, like InI (you and I), irie (positive vibrations), and imam (I, me, or my).

There is also an intrinsic connection between how language sounds and what it means for Rastas. Words like "oppression" are changed to "downpression," because the first syllable in oppression is too positive-sounding for a word emphasizing a loss of freedom. Similarly, the word "dedicate" is pronounced "livicate" by Rastas to remove the connotation of death.

At its core, Rastas see English as a language of abuse and bondage. For them, dreadtalk is "an ideological attack on the integrity of the English language" (per Edmonds). By refusing to use standard English or Jamaican patwa and infusing their own Rasta culture into the new creole, dreadtalk is another form of rebellion against Babylon for the Rastas -– just like dreadlocks.

The Jamaican government tortured hundreds of Rastas in the 1960s

One of the most tragic events in Rastafari history is the 1963 Coral Gardens incident. The incident stemmed from a dispute a year earlier between a Rasta named Rudolph Franklin and a Jamaican police officer who had shot him five times and left him for dead (via the Jamaica Gleaner). Afterward, Franklin was given a six-month prison sentence for possession of cannabis, which, coupled with frequent run-ins with the law upon his release, infuriated him.

As revenge, Franklin decided to blow up a gas station in Coral Gardens, the Ken Douglas Shell service station. Franklin and his accomplices all died in the explosion, along with three civilians and two police officers. Two more accomplices were later tried and hanged for their roles.

As tragic as the explosion was, the aftermath was just as shocking. The Jamaican government reportedly rounded up more than 150 Rastas and arrested them. The vast majority had no knowledge of or involvement with Franklin and his plan, but they were subjected to horrible violence and torture at the hands of police officers. In the documentary "Bad Friday," survivors recalled their harsh methods. One Rastafarian was tied up with a rope around his body and dragged into custody, and another was threatened with arson and violently beaten. It was not until 2017 that the Jamaican government officially apologized and set up a $10 million fund for the families of survivors (via the Jamaica Gleaner).

The transatlantic slave trade shaped Rastafarianism

It might sound a little bit strange on the surface, but the transatlantic slave trade played a huge role in the development and founding of Rastafarianism. Per Barry Chevannes in "Rastafari: Roots and Ideology," over 10 million people were forcibly removed from Africa and enslaved in the New World in the 16th to 19th centuries. Of these, roughly 700,000 were sent to Jamaica to work as either house slaves or planters.

According to Chevannes, enslavers attempted to physically and mentally subordinate African people to "instill in them ... a sense of their own inherent inferiority." Racism dominated the social hierarchy, and even free Black Jamaicans were looked down on because of their skin color. After slavery ended and enslaved people were emancipated, they became free peasants and quickly started buying up land from struggling estate owners.

However, enslaved people resisted the constant encroachments on their cultures and kept some of their own traditions alive in rebellion. Rastafari is a form of this rebellion against the ingrained racism brought to Jamaica by slavery. Academics have linked the Rastafari rebellion to other slave and peasant revolts throughout history, too.

Rastafarians believe ganja has healing properties

One of the most recognizable and often publicized aspects of Rastafari is the frequent use of and reverence for ganja (cannabis). However, while the mainstream image might be about intoxication, the smoking of ganja is a deeply spiritual endeavor for Rastafarians. Herbs are important to Rastas, and they view ganja as the "supreme herb" (per Ennis Barrington Edmonds in "Rastafari"). They use it in many forms: as a drink, as a seasoning, and for smoking. They refuse to use manufactured and commercial drugs, like cocaine, alcohol, or heroin, and view ganja as being divinely ordained for use. They look to the biblical books of Genesis and Revelation for scriptural justification of ganja, and they see it as comparable to the Christian tradition of communion.

Rastas also use ganja because it "promotes social healing by producing a sense of peace and harmony among people," and aids in both psychological and physical healing. It is used recreationally, and their smoking rituals have both African and Asian influences. The most popular form of use is smoking from an "oversized conical ganja cigar ... known as a spliff." However, they also often use a "chalice," or water pipe. Due to the patriarchal nature of Rastafari, women are sometimes excluded from smoking with the chalice, and this is typically the case among older and more traditional Rastas.

Rastafarians have ganja-induced reasoning sessions

For Rastas, the smoking of ganja is not about getting stoned and becoming giggly, contrary to some popular belief. For them, the experience is about connecting with Jah and other Rastafarians as a community. Some of the most powerful post-ganja rituals they engage in are known as reasoning (per Ennis Barrington Edmonds in "Rastafari"). Reasoning sessions are intimate spiritual conversations between two or three Rastas, where each looks to improve their mental clarity.

Nothing is off-limits for conversation during these sessions, and community members will often challenge each other in an effort to improve overall group understanding. Many Rastas undergo reasoning sessions daily, and younger Rastas look to elder Rastas for guidance, especially regarding ideas around legalizing ganja and repatriation back to Africa.

Larger reasoning sessions can include many participants, along with "ritual drumming, chanting, and dancing." They sing evangelical Christian hymns, though modified through dreadtalk to reflect Rasta cultural themes and Jah, the Rasta King, Haile Selassie.

Rastafarians refuse to eat fish longer than one foot

It is a bit surprising to learn that Rastas have a relatively well-defined food code, considering the open-ended and individualistic nature of the religion. However, most Rastas adhere to what is known as an "ital" diet, which is a primarily vegetarian and natural diet — with the exception of fish (via Leonard E. Barrett in "The Rastafarians"). They refuse to eat other meat, especially pork, believing that it harms the body by leaving parasitic worms behind.

Yet, while the Rastas do allow themselves to eat fish, they are particular about which kinds. One of the most important ital rules is that all fish have to be smaller than a foot long if they are to be eaten. The reasoning for this is that big fish are considered predators and therefore represent oppression. Rastas identify with the oppressed rather than the oppressors, spiritually, and that translates into their ital diet.

Per National Geographic, ital cooking typically does not use dairy products like butter, or salt, and organic food is of huge importance. The ital diet has even spread outside of Jamaica and Rastafarianism, and now restaurants in huge markets like New York and London have ital-themed menus.

Haile Selassie did not consider himself the Rastafari King

Though the Rastafari religion is centered around the idea that the Emperor Haile Selassie is the reincarnation of the messiah and therefore a divine being, the Rasta King did not see himself as divine in any way. According to William David Spencer in "Dread Jesus," when asked directly, Selassie quickly refuted the idea that he was in any way divine. He said he had tried to make it clear to the Rastas that he was mortal and not a messiah, and that they should "never make a mistake in assuming or pretending that the human being is being emanated from a deity." Selassie, in fact, was a devout Christian who firmly believed Jesus Christ was his savior and did not want to usurp him.

Selassie did make one visit to Jamaica during his life, for only three days, and he was besieged by locals who thought he was in fact a living god (per The New York Times). The crowd was so emphatic that he could barely get out of his private plane, and many Rastas held signs extolling his divinity and stature within the religion.

There is no current King of the Rastafari

By the 1970s, political realities had changed significantly in Ethiopia since Emperor Haile Selassie's coronation in 1930. The country was drawn into the ever-globalizing Cold War, and the monarchy and ruling classes had started to lose popular support among the people and army (per Leonard E. Barrett in "The Rastafarians"). Then, on November 12, 1974, a militant Marxist coup erupted, and Selassie was placed under arrest and deposed. Rastas in Jamaica were in shock and disbelief at their monarch being arrested and taken from the throne.

Fatefully, on August 28, 1975, after nearly a year of being under arrest, the King of the Rastafari died at 83 years old. Some elders thought the Ethiopian Crown Prince Asfa Wossen would potentially take the throne and continue the Rasta monarchy as a Haile Selassie II, but that failed to materialize during the overthrow.

Surprisingly, most Rastas were relatively unaffected by Selassie's death. For them, death is reserved for only the Babylonians, and there were no large funerals or solemnities. The movement was not set back upon his death and in fact flourished in the years following.

Many Rastafarians think reggae is sacrilegious

Bob Marley is undoubtedly one of the most popular and significant songwriters of the 20th century. His famous reggae music style became an international sensation in the 1970s, largely fueled by his 1975 album "Natty Dread" (per Leonard E. Barrett in "The Rastafarians”). Though his music propelled Rastafari into global and mainstream consciousness, not all Rastas are happy with his music or see him as a positive influence for the religion.

The House of Nyabinghi mansion is one of the Rasta groups who severely dislike Marley and his form of reggae music (per Ennis Barrington Edmonds in "Rastafari"). The Nyabinghi see it as a "bastardization" or traditional Rasta music, and equate Marley's involvement in the capitalist music industry as tantamount to being a Babylonian oppressor. They consider him a traitor to Rastafari religion.

The Nyabinghi in fact have their own distinct style of music named after them. It relies heavily on deep, rhythmic vibes and can include singing and dancing, and it is steeped in "African-Jamaican drumming traditions" (per the Smithsonian).