What Happened To The WWII German Saboteurs Who Tried To Blow Up America?

World War II was an unthinkably bloody conflict, filled with tragedy, death, and some of the most unimaginable horrors ever to unfold. But it was also full of truly bizarre stories that sound like they're something out of an ambitious but far-fetched Netflix series, probably starring Walton Goggins and Danny McBride. Take the infamous and very real Ghost Army: That was an Allied plan to mobilize artists, sound engineers, architects, and theater techs to create a campaign of misdirection that absolutely worked to fool Axis commanders. Also on the "too bizarre to be true" scale was Operation Pastorius, a Nazi plan to cut a group of saboteurs loose in America and see what kind of havoc they could cause.

"Pastorius" was a reference to Francis Daniel Pastorius, the German-born humanitarian who was one of the founding fathers of Pennsylvania, and if it seems like an odd choice, that's the Nazis for you. The idea was developed at the request of Adolf Hitler himself, who basically wanted to embarrass America while sending a warning: Don't mess with the Third Reich.

Did it work? Not exactly — and not only did it not work, but it failed in a spectacular way before literally any sabotage could happen. Read on for the true story of Operation Pastorius, then check out these other unlikely-but-true tales from World War II.

First, a little background. What was the plan?

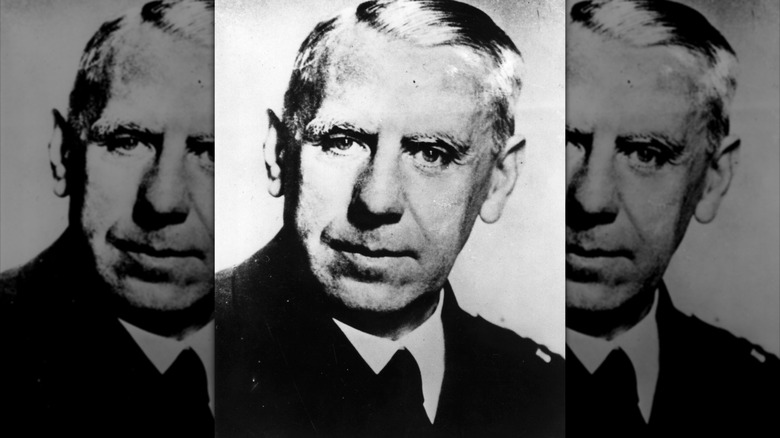

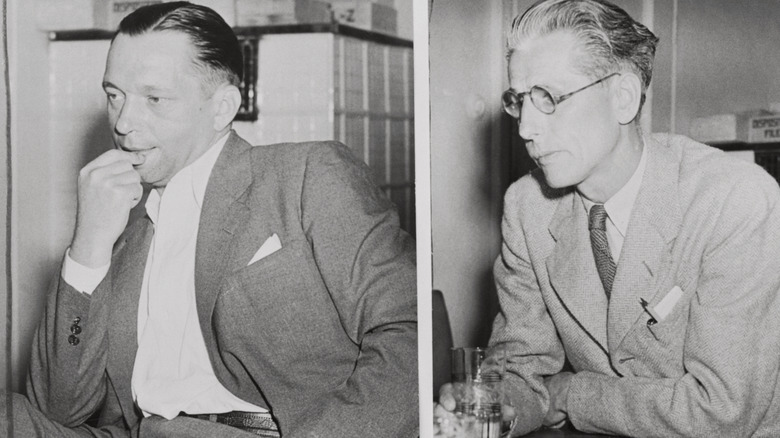

As early as 1940, Nazi spies had been scouting and mapping the U.S. for potential targets should America enter the war, and although that group was busted in 1941, the precedent was established — and the information was out there. When Adolf Hitler decided that he actually wanted to send in teams to start blowing things up, the planning fell first to Wilhelm Canaris (pictured), a World War I intelligence agent who ended up at the head of the Abwehr, Germany's military intelligence outfit.

Under Canaris was Walter Kappe, who took care of the hands-on things like recruitment and training, and who was in line to run the operation once it got under way. The choice of Chicago as a base of operations isn't entirely surprising: In addition to being a central location, Kappe lived there before joining up with the Third Reich. The heart of the plan was pretty straightforward, and saboteurs were to strike some blows that would cripple the very thing that would make America such a threat if it waded into the war: its production capability.

Chief among the assigned targets were facilities belonging to the Aluminum Company of America, which would have devastated the U.S.'s war machine. Taking out major sections of the country's vast transportation network — including rail lines, locks, and bridges — was also included in their instructions, with Niagara Falls' hydroelectric plant also being a prime target. Along the way, they were told to plant bombs wherever they felt like it — particularly eyeing Jewish-owned business.

Training? What's that? It'll be fine.... Surely...

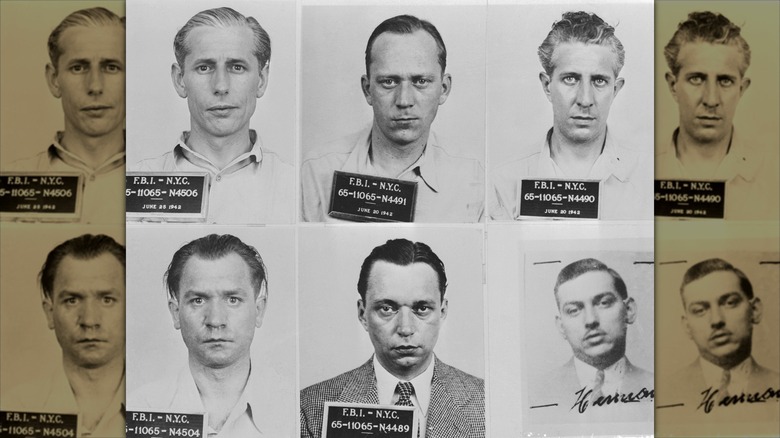

In all fairness, the saboteurs selected by the German command really didn't have much of a chance at success from the very beginning. Walter Kappe chose his point man first, a longtime New York resident named George Dasch. Together, they chose 11 others who would attend a so-called sabotage school together. That meant, of course, that they would be able to identify each other if they were captured, and it was a plan that Abwehr head Wilhelm Canaris apparently condemned from the beginning. He said (via Der Spiegel): "This is pure madness." And that was just the start.

The training grounds were outside of Brandenburg, Germany, and the men learned, well, some things. Along with some martial arts training, they also learned how to make and throw bombs, studied production facilities and learned how to pinpoint their weaknesses, and carefully crafted their cover stories. They were taught how to destroy electrical poles, studied maps, practiced shooting, and learned English — including American songs.

If it seems like there's a lot that they would need to know, there was — regardless, they had just three weeks of training. Were they already experts? Not at all: The qualifications that got them selected were largely based on their experiences in America. They'd served in various military positions and lived in the U.S. for at least a few years, but none of them had a background in espionage. This'll work out just fine, right?

Things didn't go great during their stop-over in France

The agents of Operation Pastorius were sent to France as their first stop on the way to the U.S., and that was, as the saying goes, where the wheels started to come off the cart — starting with the fact that they realized some of the American money the agents had been given was currency that was no longer in circulation. Things were already looking so dismal that one of the men in charge, Captain Wilhelm Ahlrichs, reportedly said (via Der Spiegel), "The people wouldn't be able to hold out for four weeks. [They are] adventurers who wanted to have a decent steak on their plate again."

Ahlrichs' estimate would turn out to be wildly optimistic. But first, France. That's where one agent got so drunk that he proclaimed to an entire hotel that he was definitely a secret spy man on his way to cause some chaos in America, while another one got into some trouble when he refused to settle up with a sex worker and ended up drawing all sorts of attention to himself.

Was that it? Nope: George Dasch, the first man selected for the team, had managed to lose a pile of incriminating documents before even getting to France, and although the papers could have blown the whole thing wide open, it would seem that luck was on his side. Meanwhile, France was the end of the road for one of the agents: After contracting a severe case of gonorrhea, one man left the project.

The Hamptons team and a botched bribe

The story of Operation Pastorius reads like an episode of "Mr. Bean" from the very beginning, and it doesn't get any less weird. The saboteurs split into two teams when they left France, with one group heading to New York and the other to Florida. Unfortunately for the New York team, they hit a sandbar and had to walk the last 100 yards, which got the attention of a nearby Coast Guard officer named John C. Cullen. Cullen was immediately suspicious of the strangers who claimed to be fishermen then offered him a $260 bribe: It was George Dasch who told him (via the Smithsonian), "Take this and have a good time. Forget what you've seen here."

Cullen definitely did not forget, and when he returned with backup in the morning, they found a pretty clear indication of what was going on. Footprints and a very obvious shovel led them right to where the crack team had buried the explosives they'd brought with them. The German cigarettes they'd been smoking were pretty suspicious, too.

Meanwhile, the Florida team had better luck. They landed at Ponte Vedra and simply waded ashore in bathing suits... and military hats. Why? The hats were a decision made in the hopes of ensuring they'd be taken as prisoners of war rather than accused of spying if they were captured.

Several of the saboteurs decided not to wait to be captured

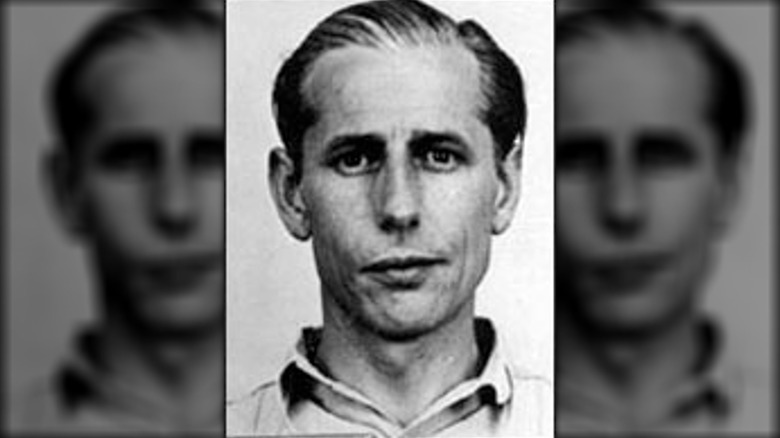

There's a few different versions of what happened when the New York team left the Long Island beach. According to Captain Wilhelm Ahlrichs, there had always been signs that George Dasch (pictured) intended on betraying them: Ahlrichs would later go on record as saying that they were still training when Dasch declared that he was going to go right to the FBI upon landing in America. Did he? Yes... but even that's complicated, and the plan seems to have taken shape when Dasch and fellow saboteur Ernest Burger found they shared a dislike for the Nazis. Burger, it turned out, had once been arrested by the Nazis and spent 17 months in jail. Minor details that should have been taken into account? Probably.

Dasch and Burger decided to turn themselves in, then offer to head back to Germany on a mission to kill Nazi leader Heinrich Himmler. Dasch called the FBI to confess, and here's where things get very he-said, she-said.

While the FBI says they were definitely right on top of things and took Dasch's call very seriously, the other version of the story is that when Dasch spoke with agent Dean McWhorter and told him that he was a Nazi spy, McWhorter told him, "Yes, yes, Napoleon called yesterday," then hung up. Dasch decided to take a train to Washington, D.C., literally knock on the FBI's door, and show them the suitcase of money he carried as proof that yes, he really was a Nazi spy.

Dasch's secret spy handkerchief led the FBI to some of his colleagues

Sources do pretty much agree that it took George Dasch about four days to get to Washington, D.C., and convince the FBI that he really was a Nazi spy. In another bizarre footnote to the story, Dasch was sort of released on his own recognizance even after his hours-long interrogation by the feds. While he headed to a local hotel, Ernest Burger was picked up back in New York City.

American authorities started apprehending the other team members, but there was a problem. Dasch — and the team leader of the Florida group, Edward Kerling — had been given a super top secret list of contacts who were loyal to the Third Reich and would give them help if they requested it. How top secret was it? It was so top secret that Dasch — who hadn't really been paying attention during this part of spy school — couldn't remember how to expose the invisible writing on the handkerchief that he was pretty sure the names were written on. (If you think a magic spy hanky sounds weird, check out Grunge's roundup of spy craft's most devious disguises, devices, and deceptions.)

The FBI, however, was front and center for this part and quickly discovered that using ammonia made the names legible, which led them to the co-conspirators. While other team members were quickly arrested, there was a side effect of this, too: When word got out about the arrest of German would-be saboteurs, countless German restaurant workers were arrested. Why? Three of the Pastorius operatives had spent time working as wait staff before becoming espionage agents.

One of the final team members to be arrested had a wild story

When Herbert Haupt was selected to be a part of Operation Pastorius, he came with a story that was so unlikely that the Gestapo reportedly didn't believe a word he was saying. The short version of it is that he was born in Germany, moved to the U.S. as a child, and at the start of the war, returned to Germany via Mexico and left behind a pregnant girlfriend. But Haupt's story was about to get weirder.

When Haupt found himself back stateside with a wad of cash and instructions to start blowing things up, he didn't do that at all: Instead, he confessed everything to his parents, bought a new car with the money he'd been given, proposed to his girlfriend, and then went to the FBI to apologize for not registering for the U.S. draft. By that time, the FBI was onto Haupt, but hoped he could lead them to the last man. When that didn't immediately happen, they arrested him. He spilled the beans pretty quickly, and Hermann Neubauer was taken into custody at a movie theater.

The FBI basked in glory it didn't really earn

Historians who have sifted through the countless documents related to Operation Pastorius have found that it was a bit of a train wreck on both sides of the tale, and it definitely didn't stop after the arrests were made. The public was told that a Nazi spy ring had been broken up in July 1942, but there was no mention of George Dasch's betrayal. FDR's attorney general, Francis Biddle, would later explain in his memoirs (via The Washington Post), "It was generally concluded that a particularly brilliant FBI agent, probably attending the school in sabotage where the eight had been trained, had been able to get on the inside and make regular reports to America." Which, of course, didn't happen.

Official internal memos were filled with inaccuracies, too — including one in which J. Edgar Hoover (pictured) had apparently changed the dates of Dasch's encounter with the FBI, painting him as an elusive spy instead of a turncoat who'd literally walked into the agency's office to turn himself in.

That's not to say that the FBI hadn't been looking for spies. In the months following Pearl Harbor, thousands of people were arrested just for having German, Italian, or Japanese heritage. By the end of the war, around 150,000 people, including tens of thousands of American citizens, had been sent to America's World War II internment camps.

The military trial was highly controversial... and very secret

With the Nazi spies arrested, there was then the question of what to do with them. It was decided that they would be tried in a military court, which had one major advantage — proceedings were confidential, and it meant that George Dasch's role in bringing down his comrades would remain a secret. As for Dasch, it was fairly easy to persuade him to keep his actual role silent, as he still had family back in Nazi Germany who would likely pay the ultimate price if his betrayal went public.

Evidence against the men was also kind of lacking — so lacking, in fact, that there were fears that charges might not even stick. FDR, on the other hand, was so determined to see the death penalty handed down that he called it (via the UMKC School of Law) "almost obligatory," and formed a military tribunal to hear the case. That was in July 1942 — on August 3, all eight were sentenced to the electric chair. Two — Dasch and Ernest Burger — had their sentences commuted to 30 years and life in prison, respectively, thanks to appeals for leniency by J. Edgar Hoover and attorney general Francis Biddle. On August 8, over the course of about three hours, the other six men were executed via the electric chair.

The way the case was tried was almost immediately controversial. Within months, military law experts found there was quite a bit that went against wartime laws, while back in Germany, Adolf Hitler condemned the whole sorry plan and reportedly said, "Why didn't you take Jews for that?"

What happened to the two saboteurs who weren't executed?

So, what happened to George Dasch (right) and Ernest Burger? That's a surprisingly difficult question to answer. History does remember that in 1948, both were sent back to Germany after serving six years in prison. That was on the recommendation of a new attorney general and under the watchful eye of a new president, Harry S. Truman. But what then?

Der Spiegel has the best information out there, and says that Burger ended up settling in Bavaria. He went back to his old trade — that of a toolmaker — and then promptly disappeared from the historical record. Dasch, meanwhile, returned to Berlin and got the attention of the Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, or the Socialist Unity Party of Germany. He was at least briefly under surveillance as a suspected American spy, and it seems as though his past as a turncoat followed him for the rest of his life. He was forced to move regularly until his death in 1991.

Interested in learning more about World War II's lesser-known players? Click here for stories like the tale of Juan Pujol Garcia, the spy who was turned down by the Allies, then took it upon himself to become one of the most successful double agents of the war.

A memorial to their memory was a long-held secret

Such a weird story deserves a super weird ending, and that kind of happened in 2017. According to The Washington Post, workers from a power company were going about their perfectly ordinary day when they stumbled across a rather discreetly placed monument dedicated to the six executed spies.

At the time, the story wasn't well known — when National Park Service resource management employee Jim Rosenstock heard about the monument, it sent him down a rabbit hole of weird World War II history. Rosenstock uncovered a lot of the story — which had been publicized before but strangely buried, much like the monument. Rosenstock was also interested in where the monument had come from, and had it been put there by white supremacists? Of course it had.

Initials on the monument — NSWPP — were connected to the National Socialist White People's Party, which was also known as the American Nazi Party. What he wasn't able to discover was when it had been installed, how it had come to be on federal land, and why on earth they'd decided to put it on the grounds of a wastewater treatment facility. It's now thought that it was there for at least a few decades, but the "why" is less clear. After determining that it wasn't a grave marker of any kind, the monument was removed in 2010. In true Indiana Jones fashion, it was given a number and relegated to an unnamed, unspecified storage facility somewhere in Maryland.

For more stories about the Nazis' worst nightmares, click here.