The Spy World's Most Devious Disguises, Devices, And Deceptions

We all know that along with his latest tricked-out sports car, super spy James Bond never begins a mission without some clever devices supplied by gadget master Q. As noted by Popular Mechanics, whether it's an explosive ghetto blaster — a "boom box that really goes boom" — a wrist-mounted dart gun, or a bagpipe flamethrower, Bond always operates with the most devious of devices. While some of the crazier Bond gadgets are truly the stuff of fiction, many others are the types of tools used in actual spy operations.

Of course, the tradecraft of espionage isn't limited to gizmos. According to Encyclopedia, tradecraft — "the methods by which an agency involved in espionage conducts its business" — also includes the various ways intelligence officers take precautions to avoid detection. Tactics of deception, including disguises, ruses, and cover identities, are as vital to successful missions as any gadget. Over the centuries, secret agents, from George Washington's spymaster Major Benjamin Tallmadge to Robert Mendez of "Argo" fame, have used both devices and tactics of deception to accomplish their history-changing espionage. As noted by the BBC, some spy tricks, such as invisible ink and single-use codes, have been around forever and are still employed by agents today. When it comes to tradecraft, it's often the most devious — not the most elaborate or high-tech — measure that gets the job done.

Devious devices sometimes come in gross packages

According to the CIA Museum, during the Cold War, the CIA came up with an ingenious method for keeping their seismic intrusion detectors safe and secure. Exploiting people's natural repulsion for excrement, they hid the detectors in fake poop. Each poop device was designed to blend in with the terrain and resemble animal scat common to the area. Tiny power cells fueled the disguised detectors, and data collected was transmitted through built-in antennas via coded impulses. From inside the icky casings, the detectors could sense movement of any person, animal, or object up to 300 meters away. Fake poop also concealed devices that transmitted radio signals to coordinate airstrikes and reconnaissance, according to the International Spy Museum.

Dead drops — defined by the International Spy Museum as secret places "where materials can be left for another party to retrieve" — also got the repellent treatment. Typical dead drop receptacles, according to WiseGeek, include public trash cans, toilet tanks, and nooks in trees. But on occasion, the CIA was known to use hollowed-out dead rats, as reported in Popular Science. For the dead rat dead drop, materials were placed inside the gutted and treated critter through a slit in its underside. CIA officers enhanced the gross-out factor by constructing rubberized guts to spill out of the carcass, according to "Spycraft" (via NY Daily News). To discourage cats from taking off with or disturbing the materials, the dead rat devices were doused with hot sauce.

It's a bird, it's a plane, it's a devious device?

As noted by the Library of Congress, homing pigeons carried their first battlefield messages in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War. In World War I, in addition to life-saving message delivery, armies started employing the birds to conduct reconnaissance photography. Tiny cameras attached to the pigeons' chests with a harness would snap photos as the birds flew over enemy territory. This practice continued at least into the 1970s, according to the BBC, when the CIA developed an elaborate plan to train pigeons to take photos over Soviet shipyards.

During the Cold War, the CIA expanded the avian spy team to include ravens and falcons. (Cockatoos were apparently considered for testing as well.) As part of the bureau's Operation Tacana, one raven was trained to drop off and retrieve small objects, including listening devices, from inaccessible window sills. The raven would locate the target via a flashing red laser beam and be guided home with a special lamp.

Not all flying spy creatures were birds or even animate. According to the CIA Museum, in the 1970s, the CIA developed the insectothopter, a micro unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), for use in intelligence gathering. Resembling a dragonfly, the insectothopter consisted of a tiny engine that flapped the device's wings, gasoline that fueled the engine, and rear ventilation that supplied extra thrust. Although the insectothopter performed well in simple test flights, it proved difficult to control in crosswinds and was never utilized.

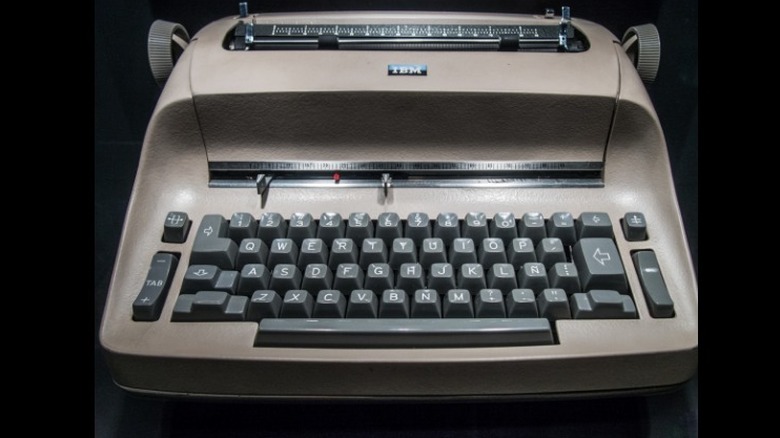

Pencils and Selectrics are mightier than the sword

As noted by Popular Mechanics, America's adversaries can take credit for some of the spy world's most devious gadgets. In the 1970s, after the identity of several secret agents working out of the U.S. Embassy in Moscow were exposed, suspicions grew that the building had somehow been compromised. Charles Gandy, an electrical engineer from the National Security Agency, was tasked with figuring out how sensitive information was being leaked to the Soviets when sweeps of the building had found no evidence of transmitters. After a part-by-part inspection of the embassy's electronic devices, Gandy deduced that the KGB had duplicated and replaced pieces of one office IBM Selectric typewriter and rigged them to transmit the typist's keystrokes using their over-the-air TV signals.

Pencils also proved to be sly tradecraft items. As detailed by the International Spy Museum, during World War II, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) managed to turn an innocent-looking pack of pencils into a deadly incendiary device. A time-delay feature allowed the operator to set off the explosion and flee unharmed. The British also used pencils to disguise guns and knives, according to "World War II, the Definitive Visual History." Shaped and decorated like a pencil, the pistol pencil was actually a 6.35mm caliber gun that fired bullets from its top section. To make a knife pencil, spies inserted a tiny knife into an otherwise ordinary pencil, an alteration that could pass any inspection.

Devious clothes can make the spy

While the attire of most spies isn't as elegant as a Tom Ford Bond suit or a Mata Hari bejeweled breastplate, it's usually a lot smarter. As detailed in a Wired interview, for decades, spies from America to the Soviet Union altered topcoats to conceal cameras. One version consisted of a palm-sized camera whose button-like lens could be inserted through an overcoat buttonhole. Photos were snapped through a trigger housed in the coat's pocket. According to the International Spy Museum, in the 1980s, four female German Stasi agents devised a bra that hid a sub-miniature camera behind its lacy front center gore. Female agents would wear the "Meadow" bra with a low-cut summer dress and snap photos via a pocket remote release. While never used as a handheld phone — "Get Smart" style — shoes were sometimes turned into eavesdropping devices. During the Cold War, as noted by the International Spy Museum, Romanian Secret Service agents slipped a tiny microphone in the heel of an American diplomat's shoe while it was being repaired by a cobbler.

Accessories were also repurposed for espionage. As noted by the CIA Museum, a spy's makeup compact might actually contain coded messages, readable only when the compact mirror was tilted at a certain angle. Other camera-hiding accessories included wrist watches, cigarette cases, and match boxes. Cyanide suicide pills were hidden in eyeglass arms, so if captured, an agent could chew on the arm to release the poison.

Devious guns are the ultimate concealed weapon

No spy kit would be complete without a gun, and over the decades, espionage designers have come up with a host of fascinating ways of disguising and hiding them. As detailed in Popular Mechanics and immortalized in Quentin Tarantino's 2009 film "Inglourious Basterds," during World War II, the U.S. Navy and the RF Sedgley company developed a single-shot .38 caliber gun that could be concealed inside a heavy work glove. The gun's muzzle and a plunger were mounted alongside each other, and to fire, the wearer would make a fist and depress the plunger with a hard punch to the target.

According to History on the Net, during the Cold War, the Soviets built a pistol that resembled a tube of lipstick and could shoot a small but lethal bullet. Nicknamed the "Kiss of Death," the pistol fired when the bottom of the tube was turned. For male agents during World War II, according to War History Online, British spies could use a small gun that resembled an ordinary tobacco pipe.

Firearms have also been hidden in — and disguised as — flashlights. According to the International Spy Museum, in one such 1930s device, a flashlight was modified to house a small firearm capable of shooting bullets. According to ABC News, the kit of a North Korean assassin captured in South Korea contained what appeared to be a flashlight but was really a three-bullet gun with a hidden trigger mechanism.

A spy's best tool might be a devious device in a private place

Along with gadgets designed for executing operations, the CIA developed unusual devices, like the rectal tool kit and the false scrotum, to help operatives escape capture. The rectal tool kit, according to the International Spy Museum (via Atlas Obscura), worked like a suppository and was carefully designed with a tight seal, a smooth, non-splintering surface, and a sturdy composition. Inside the metal tube were small versions of common tools that could be used to pick a lock, dig a tunnel, carve a hole, or execute some other form of escape. Drill bits, saws, wrenches, chisels, and knives were among the tools included in the not-for-the-squeamish anal kit.

The false scrotum — or scrotum concealment device — was designed by the CIA in the late 1960s to hide escape tools in situations where a strip search was likely. According to an International Spy Museum official who spoke to the Daily Mail, the prototype was created specifically for use by downed pilots. The belief was that enemy security guards would be uncomfortable searching the pilot's genital area and wouldn't get close enough to notice the subterfuge. The lifelike scrotum, supposedly moulded from the real thing, was made of latex and was attachable by glue. Tucked inside the artificial scrotum was a small escape radio. The false scrotum was never used in the field because the CIA director at the time, Richard Helms, became so embarrassed during its demonstration that he declined to approve it.

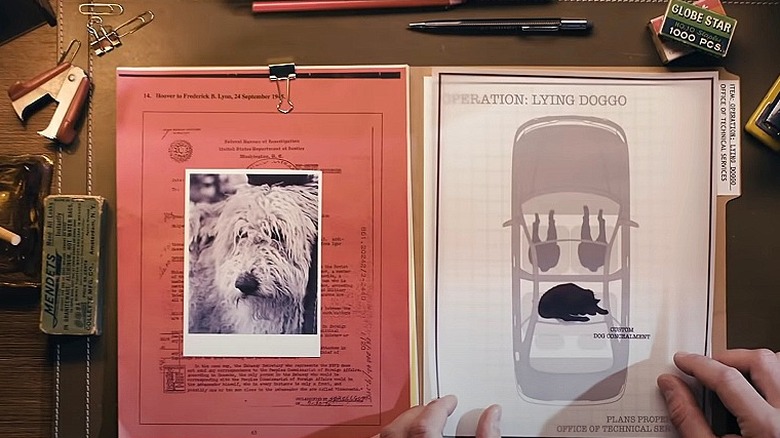

Sometimes a spy's best friend really is a dog

According to a Wired interview, one of the agency's most complicated spy ruses, used to secretly transport an operative, was called the Lying Doggo. (The term "lying doggo," as defined by the New York Times Magazine, is British slang for laying low to avoid detection.) At the direction of the CIA, a spy couple stationed at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow acquired a large, cord-coated dog as their pet. They then established a routine of driving their car in and out of the compound with the dog in the back seat, sometimes sitting up, sometimes lying down. At the CIA, meanwhile, a wigmaker constructed a furry cover that resembled the dog lying down. At the appointed time, the couple placed the fake dog in the back seat, under which an operative was hiding, and drove from the embassy in their usual manner. The "lying doggo" fooled the embassy guard, and the operative departed undetected.

As detailed in the same Wired interview, another similar deception, called the Jack-in-the-Box, was designed to allow a CIA case officer to slip out of a car while being followed by an adversarial surveillance team. After some diversionary maneuvers by the car's driver, the officer would quickly exit and be replaced by a dummy that would pop up from a secret compartment. When the surveillance team caught up to the car, they would see the expected two silhouettes and assume all was well.

In the face of danger, they face off

While spy tradecraft relies heavily on clothes and other neck-down details to pull off escapes and create cover identities, it doesn't neglect the face. Simple facial disguises include wigs, beards and moustaches, and eyewear. Every CIA operations officer receives a disguise kit, which includes facial disguises as well as materials to prepare and apply them, according to the International Spy Museum.

As described in a Wired interview, for face-to-face meetings, however, operations officers will apply advanced disguises to deceive their target. Advanced disguises often feature custom prostheses, cheek plumpers, dental facades, and other inserts that change the shape of the face. The most complex and devious facial disguise, introduced in the 1990s, was the Semi-Animated Mask (SAM). According to an Atlas Obscura interview, the SAM, nicknamed "the five-second mask — five seconds on, five seconds off," (via Wired) was designed for situations requiring a convincing and quick identity change. The full-faced latex mask was molded from the officer's own head, then was modified to change everything from ethnicity to age. For safety and convenience, it was also designed to crumple into a small ball after removal.

More recently, as described by the International Spy Museum, artist Leo Salvaggio created the URME Anti-Facial Recognition Mask as a counter-surveillance device. When an operative dons the prosthetic mask, which has been 3-D printed from Salvaggio's own face, any facial recognition software the operative encounters will identify the image as Salvaggio's, not the operative's.

They're watching you watching them

Though not as sexy as surveillance techniques, counter-surveillance measures can be equally devious and vital. Based on what they reveal, an agent might decide to abort a planned operation and spend the day doing nothing. According to a Wired interview, CIA case officers housed in Moscow's U.S. Embassy compound were subjected to constant live surveillance. Walls were bugged, and KGB teams would follow the operatives everywhere. To detect KGB presence in the field, the CIA devised the SRR-100, a portable listening device consisting of three parts: Phonak ear pieces, an induction neck ring, and a receiver that was tuned into KGB surveillance frequencies. The ear pieces were hidden behind a mold of the officer's inner ear, and if the neck ring and receiver picked up any KGB communications, the officer would hear the chatter and know to lay low.

Equally clever but decidedly low-tech counter-surveillance measures were also used to elude detection, according to the BBC. In East Germany, the Stasi's technique for preventing electronic surveillance in their offices was to build clear plastic furniture that would make hiding bugs impossible. They also installed inexpensive soundproofing and white noise machines to muffle their voices. More recent low-tech counter-surveillance measures have included the "sneakernet" technique, in which operatives copy messages from anonymous email accounts onto a USB stick and pass the stick back and forth between them, and using "saved drafts" folders on a shared email account to avoid creating a traceable cyber trail.

Devious devices, disguises, and deceptions helped win D-Day

Probably the most ingenious and elaborate use of tradecraft by the military was D-Day's Operation Bodyguard. For almost a year during the height of World War II, according to History, Allied Forces made plans for a massive attack at Normandy. Keeping the Germans in the dark about the details was crucial to the operation's success, and to maintain secrecy, the Allies devised a multi-pronged strategy of deception. First, they had German double agents pass false information about the invasion to the Nazis, then enhanced the misinformation with phony radio chatter about cold weather projections. Hitler responded by sending troops to Scandinavia.

They then tricked the Germans into thinking the invasion would take place in France's heavily fortified Pas de Calais region. In addition to hours of misleading radio communications, the Allies created an entire fake attack force to fool Nazi aerial reconnaissance planes. Inflatable Sherman tanks were moved around on rollers, and decoy landing crafts and dummy aircraft were set up on the River Thames. They even hired an actor to impersonate General Bernard Montgomery and make strategic appearances in spots monitored by the Nazis.

During the actual attack, dummy paratroopers, fake radar signals, and other ruses were employed to keep the Germans distracted. The final deception occurred days after the invasion when a Spanish double agent convinced Hitler that General Patton was planning a bigger attack at Calais, thus delaying the sending of German reinforcements and ensuring Allied victory.