The Untold Truth Of America's WWII Internment Camps

It almost didn't matter where you lived in the 1940s, the world was a terrifying place to be. World War II reached every corner of the globe, and sure, people were scared. But people also made a lot of bizarre decisions, starting at the top. We're all familiar with Germany's concentration camps, where people who were deemed undesirable or a threat were sent to live... and oftentimes, die. That's awful, but surely, that was something that only the bad guys did, right? Right?

Not so fast. In one of those chapters of American history that usually doesn't get taught in schools, the US absolutely did it too — just, a little differently. Around 120,000 Japanese living in the US — 80,000 of whom were American citizens — were forcibly incarcerated in camps. Exactly what they're called, well, The Huffington Post says that's important. They're commonly called internment camps, but they suggest "incarceration" camps are more accurate. And the president at the time? FDR called them concentration camps, once asking, "What arrangement and plans have been made relative to concentration camps in the Hawaiian Islands for dangerous or undesirable aliens or citizens in the event of national emergency?"

This is going to get real.

Internment camps started with good, old-fashioned racism

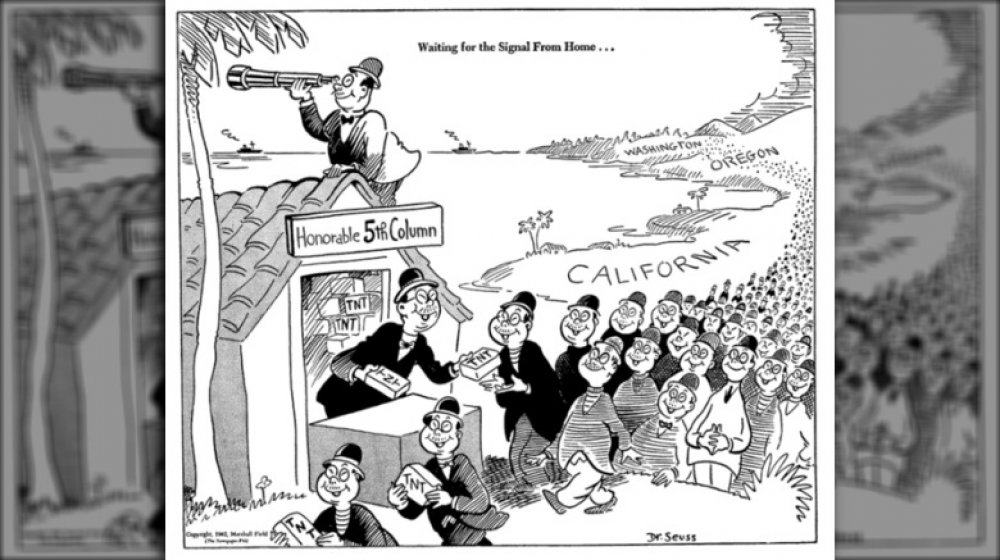

On December 7, 1941, Japan carried out their infamous attack on Pearl Harbor. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared war on Japan the next day and meanwhile, there was something else brewing at home. Within just three months, Japanese Americans were officially considered the enemy, too. That's in spite of the fact organizations like the FBI and the US Justice Department had conducted extensive investigations and determined that the Japanese population of the US was not a threat. That's worth a repeat: they were not a threat. Still, propaganda — like the Dr. Seuss cartoon pictured, insisted otherwise.

According to Quartz, a lot of it was about money. When many Japanese moved to the US, they set up in California and became farmers. They were incredibly successful: in spite of laws limiting their rights to buy land, the National Archives says they still produced more than 10 percent of the state's crops. White farmers suddenly found themselves with some serious competition and, well, it's best we let people speak for themselves sometimes, so let's share what Austin Anson, head of the Salinas Vegetable Grower-Shipper Association had to say about Japanese farmers:

"We're charged with wanting to get rid of the Japs for selfish reasons. We might as well be honest. We do. [...] They came into this valley to work and stayed to take over. [...] And we do not want them back when the war ends, either."

And the government heard the unrest.

Kicking off an irrational panic — here's who to blame

Anti-Japanese sentiment came right from the top, and no one sums up the attitude better than the army's West Coast commander, Lt. Gen. John DeWitt. He's the one who said (via Quartz): "The Japanese race is an enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese born on United States soil, possessed of United States citizenship have become 'Americanized,' the racial strains are undiluted." The National Archives says he's also the one credited with saying, "A J**'s a J** — it makes no difference whether he is an American citizen or not."

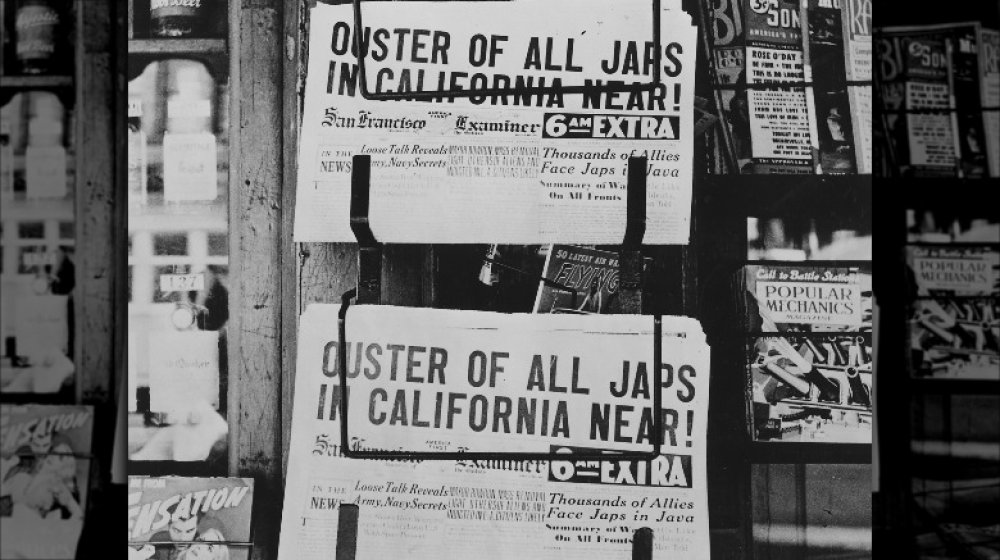

It wasn't long before FDR listened in a big way. When he signed Executive Order No. 9066 on February 19, 1942, he gave the US army the power to create zones where "any or all persons may be excluded." Even as newspapers ran fabricated stories of espionage and sabotage, and the FBI denied there was a hidden threat lurking on the West Coast, the mass incarceration of Japanese citizens was deemed a "military necessity," according to the National Park Service.

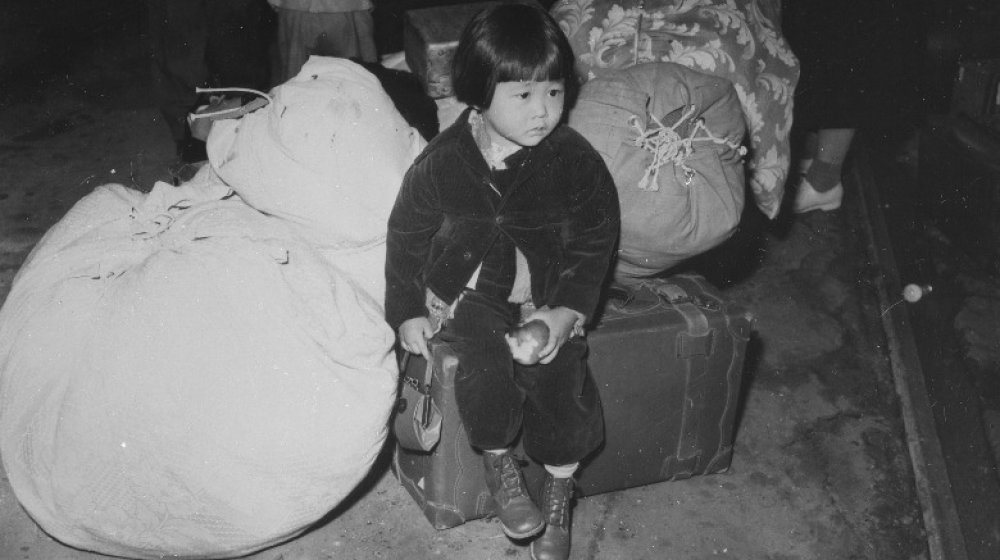

What followed was the establishment of areas where no one of Japanese ancestry was permitted to live. While several thousand Japanese Americans did try to voluntarily move, that proved difficult — the government had already frozen their assets, and they quickly found other states didn't want them, either. Those who didn't leave were rounded up by the Wartime Civil Control Administration, and relocated to "War Relocation Centers."

From WWI veteran to suspected traitor

It's almost impossible to imagine suddenly being told you're such a threat to your own country that you'll need to go live in something the president called a "concentration camp" for the foreseeable future, and for many, it was simply unfathomable. The Tribune did a deep dive into the life of one of the Japanese Americans faced with relocation, and found that records can't even agree on how he spelled his name. We'll go with what they found on his military draft card: Hideo Murata.

Born in Japan, he moved to the US sometime before signing up for military service in 1917. He served in World War I, and while his military records haven't been found, we do know that he distinguished himself with actions that earned him an honorary citizenship and an official thank-you from the government on his return. Fast forward to 1942, and he was handed another official document: one saying he was now an enemy of his country, and he needed to move to an incarceration camp.

He went to the sheriff and pleaded to stay in his home but was told there would be no exceptions made. Rather than move, he took a lethal dose of strychnine and died — still holding the official paper that gave him American citizenship. He was 52-years-old, and buried in an unmarked plot in the Arroyo Grande District Cemetery.

'Let's Obey Order Loyally'

There were essentially two reactions to the evacuation orders, and the one that was promoted by the Japanese American Courier was one of "loyalty." The paper — the first Japanese paper published in English in the US — wrote (via Oberlin College): "If the Japanese people had been permitted to remain, it would have given them an easier way of demonstrating their loyalty; but now it will have to be the difficult way of proving that loyalty which they have long proclaimed."

And that's what some did. When the JACL interviewed Bill Hosokawa about the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming, he put it this way: "There was anger and frustration and bitterness and despair, [...] But there was the feeling that, 'By God, if this is what we are called on to do, we will do it.'"

But that wasn't the case everywhere. The National Park Service says that there were a few instances of people who tried to hide rather than be evacuated, and at least one farmer who — when he was denied an extension to stay and harvest his crops — plowed his fields of strawberries instead. He was arrested: since food was crucial to the war effort, they claimed it was sabotage... even though they had already told him he wasn't allowed to harvest.

The murders at Lordsburg

The Lordsburg Internment Camp was the only purpose-built relocation camp used, says the National Japanese American Historical Society. The 1,300-acre facility was located in New Mexico, and was home to around 1,500 Japanese Americans.

The Huffington Post says it was also the worst of the worst, and much of the treatment and orders handed down by Colonel Clyde Lundy was so harsh it was in violation of the Geneva Convention. Those held there were forced to build military facilities (it would later be used to house Italian POWs), and in spite of the fact that the Geneva Convention specified that prisoners who tried to escape couldn't be executed, that's what happened at Lordsburg.

On July 27, 1942, guards at Lordsburg shot and killed Hirota Isomura and Toshio Kobata. The two men were shot in the back, and guards later said they were trying to escape. But according to Densho, Kobata suffered from breathing difficulties as a lifelong consequence of tuberculosis, and Isomura was suffering from a spinal cord injury. The guard who shot them was acquitted of any wrongdoing, and the men's deaths are two of seven recorded cases where those confined to the camps were killed by gunfire.

Life in the internment camps was pretty terrible

History says that the US government definitely tried to paint what they were doing with a rainbow brush of happiness. By 1943, they were releasing films that claimed to show happy families in their camps, all content they were doing the right thing for their country. America was safe! Yay!

The reality was much, much different. The camps were often located at abandoned fairgrounds and racetracks, meaning the buildings that were already there were used... and many families found themselves living in horse stalls. The Digital Public Library of America says that oftentimes, as many as 25 people would be crowded into space meant for four. There was no privacy, shared bathroom and laundry facilities, and little in the way of heat or ventilation. Disease spread quickly, and camps were breeding grounds for everything from smallpox to typhoid. Food poisoning was common, supplies were scarce, and through it all, many were put to work in the surrounding fields.

As if that wasn't bad enough, those sent to the camps have something eerie in common with those sent to the Nazi concentration camps in Europe. When NPR spoke with Riichi Fuwa in 2017, the 98-year-old could no longer remember his Social Security number. But he could still remember the number he had been given when he was sent to the camps. "19949. That was my number the government gave me. 19949. You were more number than name."

The sport that many in internment camps credited with saving them

Those confined to incarceration camps did the best they could to help life go on as normal, and that included setting up schools. They were usually incredibly crowded, says the Digital Public Library of America, and supplies were next to non-existent, but it still gave students the basics: math, science, social studies... and along with that? The War Relocation Authority insisted that students also be schooled in American values.

But more important than education? Baseball. Many camps had their own "official" baseball teams, and they were even allowed to travel. In 1944, Gila River took on Heart Mountain in a 13-game series and won... and that sounds like a sentence that could apply to any kind of sport. But Gila River and Heart Mountains were internment camps. And it was about more than just sport, says the National Museum of American History: it was also a way for immigrants to participate in a truly American pastime.

One of those incarcerated in the camps was George Omachi. Not only did he say, "Without baseball, camp life would have been miserable," but he went on to become a scout for MLB. Other stars came out of the camps, too: like Kenichi Zenimura, who was known as the Dean of the Diamond, and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame for his work in desegregating the game (via KVPR).

Those who died in internment camps

According to Densho, the goal of the WRA was one inpatient and one outpatient hospital in each camp, and while they technically achieved that, care was less than stellar. Medical staff who walked into camp hospitals found something less like a hospital and more like a first aid station: even the most basic supplies were limited, equipment was simply not there, and it took months for new shipments of supplies to arrive. Conditions were dire: in one camp — Poston — one of the doctors had to fight to get the windows in the surgical room sealed against dust and dirt from the outside.

Between May 1942 and March 1946, hospitals were acting at full capacity nearly constantly. There were 5,981 births recorded, there were a lot of deaths, too: 1,862 of them. Causes varied: 407 people who died of cancer. Others? There were 206 people who died tuberculosis, a disease which spread quickly through the crowded conditions of the camps. Another 70 died of influenza and pneumonia, and other causes included heart, vascular, and kidney disease.

The other part of the government's internment camp plan

It turns out that the government had something else in mind for the 120,000 people incarcerated in internment camps, and that was along the lines of some good ol' forced labor. The majority of those who were shuffled off to the camps had worked in the agriculture industry, and according to NPR, the government was absolutely going to use all their skills — and it was planned that way.

A large number of the administrators from the War Relocation Authority were transferred there from the Department of Agriculture. In addition, when it came time to choose the locations for the camps, favored places were among the most inhospitable: useless desert and scrubland. Why? Because they knew that camp inmates could be put to work on massive irrigation and other agricultural projects to turn that land into something viable.

Don't worry, it gets worse. One camp — Tule Lake — was situated on the rich soil of a former lakebed. People eligible to work were fined $20 a month for refusing to work the fields, and the camp grew so much that not only was the camp fed, but administrators turned around and sold the surplus on the open market. More than 2 million pounds of crops — including potatoes and daikon radishes — were grown by camp laborers.

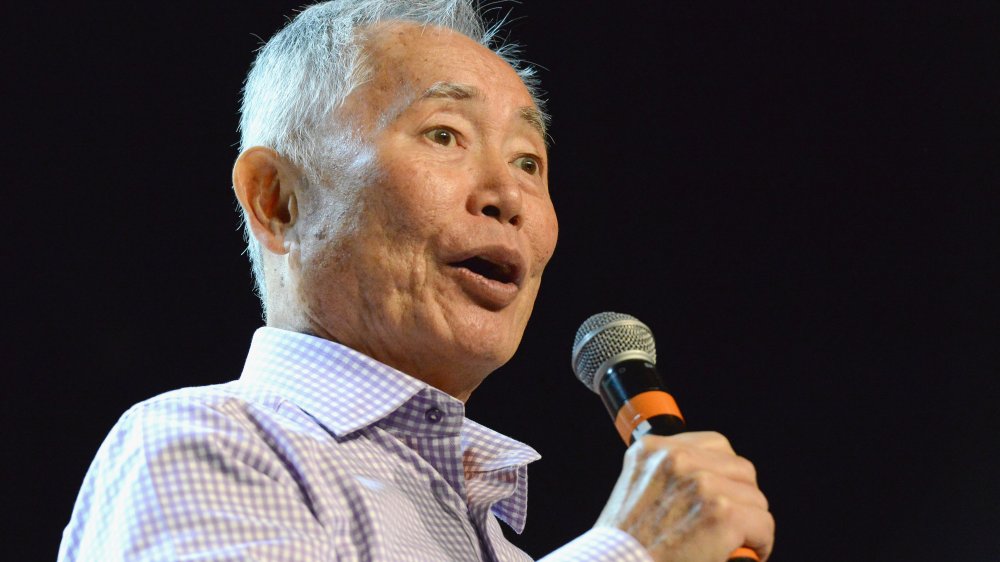

George Takei's memories of internment camps

George Takei was only 4-years-old when the incarceration order was signed, but that was old enough: he told History, "I remember my mother's tears as we were forced from our home at gunpoint. Everything they had worked for was gone, in an instant."

Takei has been both candid and vocal about his — and his family's — experiences in the camp. In his graphic novel They Called Us Enemy (via NPR), he writes about thinking it was a grand adventure, getting to sleep where horses had slept. And the barbed wire? That, another boy at the camp explained to him, was to keep the dinosaurs out. Normal life? That was communal showers, watery bowls of rice, and playing under the watchful eye of armed tower guards.

It wasn't until much later when the family was released — homeless in Los Angeles in 1945 — and he returned to public school that he realized what kind of discrimination and hate his parents had felt. In hindsight, he realized what it had been like for the women in the camp — with no walls between toilets and no sanitary products made available — and the true meaning of the word "gaman." It meant "to endure, with fortitude and dignity, the injustice of having to wait in the cold even to go to the bathroom. Throughout our time in the camp, the spirit of gaman is what buoyed us, even in the darkest of hours. [...] they could not take [...] our basic humanity."

Long-lasting effects of life in internment camps

For the 120,000 people incarcerated in the internment camps, those long, hard years left their mark. When PBS collected some of the studies done on the long-term effects of imprisonment in the camps, they found some dire things.

Signs of trauma — including feelings of low self-esteem and an accelerated loss of the Japanese language and culture — were seen in not just those who had been incarcerated, but in their children as well. Those who spoke of the trauma reported symptoms of post-traumatic stress syndrome — including suffering flashbacks to their time in the camps — but many more simply didn't speak of it. Life expectancy studies suggest those incarcerated lived about 1.6 years less than average, and were twice as likely to suffer from cardiovascular disease and premature death.

According to The Washington Post, suicide rates among internees are also higher. The majority of those placed in internment lost property, were unable to find work when they were released, and spent the rest of their lives laboring under the stigma of their experiences.

An apology only goes so far

In 1988 — 46 years after Executive Order 9066 — Congress officially apologized to those who had been incarcerated. Along with a formal letter of apology, survivors got $20,000, and the funds started being distributed in 1990 (via AAPF). Was it enough?

Pat Morita, of the Happy Days and Karate Kid fame, had this to say about his life in the Gila River camp: "I cried for four days, I was so homesick." He was 11-years-old. He continued (via Biography), "Uncle Sam and we Americans like to use euphemistic words or invent words if we think certain other words are too harsh. So they called them 'relocation centers,' but they were America's version of concentration camps."

And there's one more footnote to this story: it wasn't just Japanese Americans who were rounded up and sent to camps during the war years. In 1943, Eberhard Fuhr was removed from his Cincinnati school by the FBI, arrested, and would become one of a number of German Americans who would spend the rest of the war in a Texas internment camp. According to CBS News, thousands of German Americans and Italian Americans received the same treatment... and didn't even get an apology.