These WWII Legends Were The Nazis' Worst Nightmare

Not all events in history are appropriately named. Take the Hundred Years' War: That lasted for 116 years (between 1337 and 1453), and that's why students should always read the fine print.

World War II, however, isn't an exaggeration. Britannica says that not only was almost every country involved or at least impacted in some way, but the 50 million-odd deaths make it the bloodiest conflict in history. It's often called a continuation of World War I, because the conditions left in the wake of that war set the stage for the rise of the Third Reich.

The views and goals of Hitler and the Nazi party were so polarizing that there's not too much room for fence-sitting. Either you agreed or you disagreed, and fortunately, there were a lot of people who really, really strongly disagreed. While a cynic might condemn mankind because of the views of the Nazi party, there's another way to look at it: There were a lot of people who gave everything — including their lives — to stop the relentless, onward march of the Nazi war machine. Many of the men and women who presented the biggest problems for Nazi Germany weren't super-soldiers or the elite — they were ordinary people who put their feet down and said, "We're not going to stand for this."

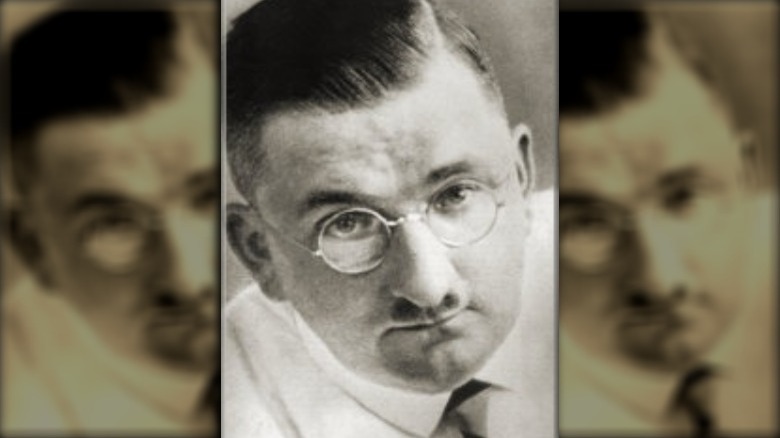

The pen is mightier than the sword

Fritz Gerlich was a member of what's arguably one of the most dangerous, most influential positions in the world: journalism. Born in Germany in 1883, he was editor-in-chief of a newspaper when he had a sit-down chat with Hitler. And he didn't like what he heard, even in 1923.

When his newspaper fell in line with Nazi propaganda, Gerlich left to start his own paper, Der Gerade Weg. In it, he made it clear that extremism wasn't the Germany he loved, and when Hitler's niece, Geli Raubal, was killed in 1931 — by the dictator's personal pistol — Gerlich made it clear just what he thought: that Hitler had ordered her death.

Gerlich went hard into the investigation into her murder and absolutely published what he found — that Hitler was involved. Spartacus Educational says that Gerlich continued to mock and ridicule Hitler in the very public forum, even using the Nazis' beloved racial sciences to "prove" Hitler wasn't even Aryan — he was, by his own definition, Mongol and Slavic. Gerlich wrote: "Hitler's attitude is absolutely un-Nordic and un-Germanic. It is ... absolute despotism ... and can be explained by the fact that this man is a typical bastard."

It's unsurprising that on March 9, 1934, Nazi stormtroopers raided Gerlich's offices, destroyed everything, and shipped him off to Dachau. He was killed more than a year later — on the Night of the Long Knives (June 30, 1934) — and his wife was mailed his bloody glasses.

The spy with the wooden leg

Virginia Hall had such a natural talent for espionage that it was only after a chance meeting and minimal training that she became one of the first spies the British sent into France. The nation was already occupied by the Nazis in 1941, and she started gathering her info by getting friendly with the owner of a brothel, who was more than happy to pass along information her girls heard from the chatty Gestapo agents who came calling.

Hall, says NPR, went on to become crucial to the organization of the French resistance while still remaining a shadowy, elusive figure. Klaus Barbie, the head of the Gestapo in France, plastered Paris with wanted posters — and did almost manage to catch her after she sprang allies from a prison camp. She escaped and embarked on a grueling hike across the Pyrenees Mountains. A shocking 50 miles later — a distance she covered while being hampered by her heavy wooden leg — she was arrested in Spain.

Once she finally made it back to Britain, they refused to send her back ... so she joined up with the Americans, filed down her teeth so she could pass for lower-class French, and kicked off a campaign of sabotage and reclaiming villages from Nazi occupiers. That's wildly impressive, especially for an agent who was, according to Smithsonian Magazine, expected to survive in Nazi territory for only a matter of days. She was never captured and died in 1982 — having never spoken about her wartime exploits.

The Soviet Union's deadliest sniper

His name was Ivan Sidorenko, and like many, he didn't find his true calling until it came and found him. Sidorenko, says ATI, was an artist who signed up with the Soviet Army at the beginning of the war.

That's when something odd happened. Although Sidorenko was originally assigned to an infantry and artillery unit during 1941's Battle of Moscow, he would regularly wander off on his own during his downtime. And that's when he found out he was really good and sneaking around and killing Germans before they even knew he was there.

The higher-ups saw some serious potential and started sending Sidorenko out to do what he had been doing on his own — usually with a student or two in tow. Not only did he teach his methods — which were based on his philosophy of "one shot, one kill" — to hundreds of other students, but by the end of the war, he would be credited with around 500 kills. And that's not just individual soldiers: Sidorenko would destroy entire supply vehicles, tanks, and tanker trucks with explosive bullets (via War History Online).

He was wounded in 1944 and was forced to sit out the rest of the war, but he and his snipers had done their job — in spite of the counter-snipers the Germans deployed solely to target them.

When swing and music was more than a lifestyle

Children are the future, it's said, and Hitler certainly thought so. According to History, every German (and non-Jewish) boy was required to join the Hitler Youth, but some kids had other ideas.

Among them were the Swing-Jugend, or swing kids. They weren't exactly an organized group of active resistors, but they showed their complete dislike of Nazi ideals by being the exact opposite of the clean-cut, disciplined, uniformed, and proper members of the Hitler Youth. These were the kids who met in secret, accepted anyone — regardless of their religion — and embraced jazz, swing dancing, and the teenage culture of Britain and the U.S.

The Swing-Jugend — with their long hair, casual dress, and crazy moves — earned the ire of Heinrich Himmler in particular. According to Facing History, Himmler targeted the "ringleaders" of the Swing-Jugend for deportation to concentration camps, where they would be sentenced for up to three years for their disobedience. Their festivals — which could attract hundreds — were described as "an appalling sight," where teens "all 'jitterbugged' on the stage like wild animals."

The rebellious actions of the Swing-Jugend escalated as the war went on, and by 1942, there were members of the group in camps like Auschwitz, Ravensbrück, and Bergen-Belsen. According to Music and the Holocaust, their rebellion continued inside, where some groups reassembled to sing for other prisoners.

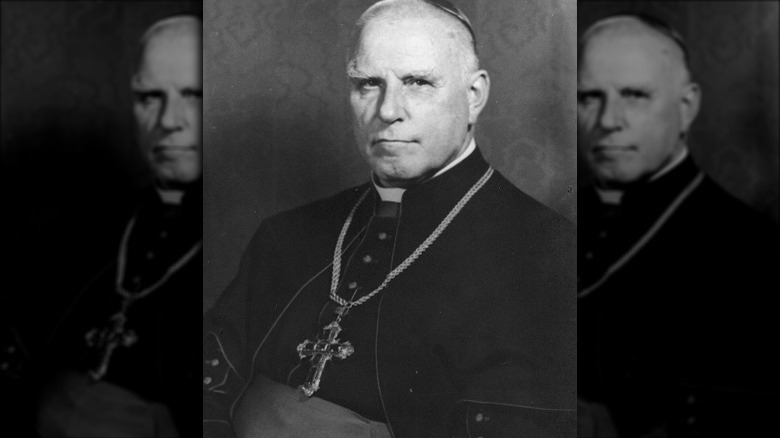

The Catholic Archbishop who took a stand

Publicly denouncing the Nazi regime and their actions was a great way to find yourself on a crowded train headed to a terrible — and often final — destination, but speaking out against Hitler's policies was exactly what Clemens August Count con Galen spent much of the war doing. And that was a huge problem for the Third Reich, because he was Germany's bishop of Munster.

In 1939, Hitler gave the go-ahead to start killing "patients considered incurable." That, says the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, became known as Operation T-4 and targeted those with mental and physical disabilities. Parents were encouraged to drop their kids off at specific locations, and by 1940, dedicated gas chambers had been set up around the country.

The program led to the deaths of at least 70,273 people and was vocally condemned by Bishop von Galen. He put such pressure on the Nazis that Hitler actually ended the program on August 29, 1941 (although the practice itself continued), and von Galen continued to speak out against everything from the Nazi theories of racial superiority to their euthanasia programs — at a time when, says the Catholic News Agency, many Catholics were claiming that the Nazi Party was "most compatible with Catholic ideals."

Von Galen's status within the church protected him from direct retribution, but that protection didn't extend to a number of the priests who repeated his anti-Nazi sermons.

The Polish midwife who gave babies a chance to know who they really were

First, a bit of background on the Lebensborn program: According to the Jewish Virtual Library, the program was, in a nutshell, started by Heinrich Himmler as a sort of selective breeding project designed to create a master race. In some cases, children who fit the racial profile were plucked from the arms of the women who gave birth to them in concentration camps, adopted into Nazi families, and never knew where they really came from.

That's where a Polish midwife named Stanisława Leszczyńska comes in. She was sent to Auschwitz in 1943, after spending four years helping smuggle Jews out of the Lodz ghetto. She was tasked with caring for pregnant women — and in this case, she quickly found out that "caring for" meant killing the majority of the newborn babies.

Leszczyńska not only refused, but she stood up to Dr. Josef Mengele to do so. According to History, no one is really sure why she wasn't executed, but she was sent back into the camp and worked to at least save the mothers that she could. Along the way, she secretly tattooed the babies who were born and then taken away to be shuffled into the Lebensborn program. It's estimated that she delivered around 3,000 babies, and about 500 were taken away and adopted into other families. Thanks to her, many had the chance to learn where they really came from.

The wild resistance of Norway's 8,000 teachers

Norway had a complicated position during the war: They were originally neutral, but the Nazi war machine invaded in April 1940 and set up an occupation, much as they did with France. What followed was a lot of German insistence that their way was now the only way and a lot of Norwegians pointing out that no, that wasn't how it was going to work at all. That sentiment was led by the nation's teachers.

The Nazis weren't just out to win the war — they were trying to lay the groundwork for the new world they wanted to see spring from a Nazi victory. To that end, they pushed teachers to feature only Nazi-friendly curriculums in their classrooms. When they tried that with Norway, around 8,000 teachers refused.

According to The Norwegian American, Hitler installed a prime minister sympathetic to the cause, and when the educational system as a whole outright pushed back, that's when PM Vidkun Quisling decided to make an example and send 499 teachers to forced labor camps that had been set up north of the Arctic Circle. Parents were almost overwhelmingly supportive of the teachers as they lived in the far reaches of the freezing north, with only cardboard shelters and supplies smuggled in from sympathetic families.

And they won. When their plight went public, they were sent home — and they never taught the Nazis' educational programs in their schools. Quisling, meanwhile, was described as "broken" by the resistance.

The dignified resistance of a German widow

Johanna "Hanna" Dotti had married Wilhelm Solf, the one-time governor of German Samoa and ambassador to Japan, in 1908, and when he died in 1936, she became not only a widow but the leader of the anti-Nazi Solf Circle.

Spartacus Educational says that their first official meeting was in 1943, under the guise of a 50th birthday party for one of the attendees. From there, they went on to use their position and influence to not only hide Jewish refugees but provide them with the falsified documents they needed to get away from a future that involved an otherwise inevitable trip to the concentration camps (via The British Museum).

The circle had both a secret weapon and a secret weakness. Their associate, Helmuth von Moltke, was conveniently a member of Hitler's military intelligence network, the Abwehr. He had already given them the heads-up that the Nazis were onto their activities and that they were going to be put under surveillance, but it was too late — one of their inner circle, Paul Reckzeh, was on the Nazi payroll as a spy.

Hanna Solf and her circle were arrested in 1944: One of the group committed suicide, while others were accused of treason and executed. Solf (pictured at the Nuremberg Trials) was sent to Ravensbrück and survived to liberation.

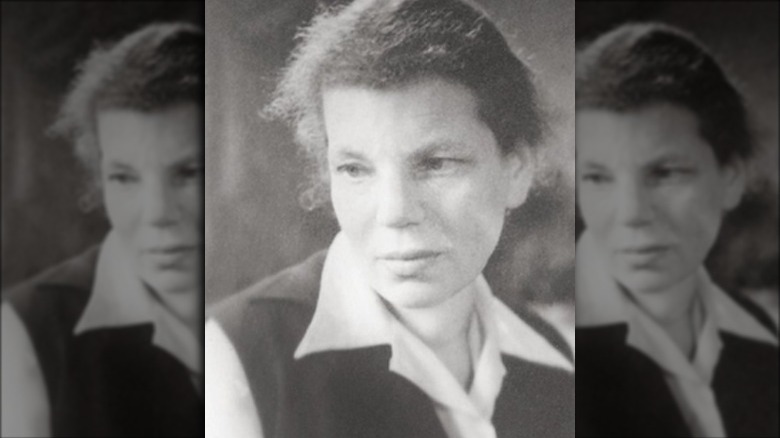

The White Rose

When talking about World War II, it's important to remember that being German and being a Nazi weren't the same things. Some — like Hans Scholl and his sister, Sophie — did everything in their power to bring down or at least damage the regime from the shadows.

According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Scholl siblings were among the founders of the resistance group the White Rose. In 2013, White Rose member Liselotte Furst-Ramdohr (pictured) explained the group's motivation to the BBC: "The war was dreadful, with the battles and so many people dying, and ... Hitler was a megalomaniac, and so they had to do something."

Furst-Ramdohr had already lost her husband to the fighting by the time she joined, and the group was in full swing. They had begun writing and printing leaflets telling the truth about the Nazi regime and encouraging resistance, while taking to the streets at night to cover the buildings of Munich in anti-Nazi graffiti. The Scholl siblings were distributing their leaflets at the University of Munich when they were arrested. They were put on trial and ultimately executed as traitors.

The Gestapo continued to hunt the remaining members of the White Rose, and Furst-Ramdohr was also arrested. After spending about a month in custody, she was released ... and trailed by the Gestapo, who were still looking for other members.

In 1943, Allied aircraft dropped millions of copies of the last White Rose leaflet across the nation.

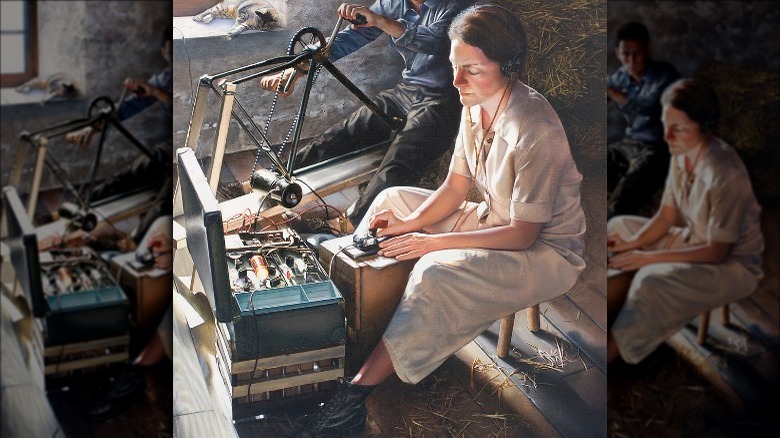

Code name: Sylvestre

His real name was Michael Trotobas, and he was — at first — a perfectly ordinary British soldier. In 1941, though, he was given the code name "Sylvestre" and sent into Nazi-occupied France as an operative for the Special Operations Executive's French Section (via the National Army Museum). By 1943, The Argus says that he was one of the most wanted agents in France.

A lot happened in the meantime. Trotobas was surprisingly arrested just a few days after first dropping into French space, and it wasn't until 1942 that he led a daring escape out of a camp near Bergerac. Completely eligible for a desk job following a jaunt through the Pyrenees mountains, he instead headed back and set up an entire network of resistance fighters that would be code-named FARMER. He managed to unite different factions of the Resistance under his umbrella and went on to organize devastating sabotage missions that destroyed Nazi facilities which the RAF had failed to take out from above.

The Gestapo offered a 1 million-franc reward for him, and the beginning of the end started when one of his nearly 1,000 agents was captured and gave up his location. In November 1943, the Gestapo swarmed the safe house Trotobas shared with his girlfriend, and both were killed.

Lady Death

When Lyudmila Pavlichenko enlisted in 1941, recruiters first tried to push her into the field of nursing. Once they realized how good she was with a gun, they put her into the 25th Rifle Division of the Red Army, and they made her a sniper. It wasn't long before the Germans were saying her name — Lady Death — in fear.

Her patience and self-control were legendary, once remaining in the same place for three days before getting a clear shot at her target. That target was just one of many, and even as she accumulated 309 confirmed kills, she faced off with German officers who, when they discovered they couldn't kill her, decided to bribe her with an officer's position in their army. She never wavered.

After being wounded for a fourth time, Pavlichenko was sent to the U.S. to raise support for the war, which she did in an epic way. After deflecting comments about her uniform and her femininity, she asked a crowd, "Gentlemen: I am 25 years old, and I have killed 309 fascist occupants by now. Don't you think, gentlemen, that you have been hiding behind my back for too long?"

According to the National World War II Museum, Pavlichenko never returned to the field. Instead, she trained the snipers who went to war after her, and her story doesn't have a happy ending. Suffering from depression and PTSD, she died in 1974 at age 58.

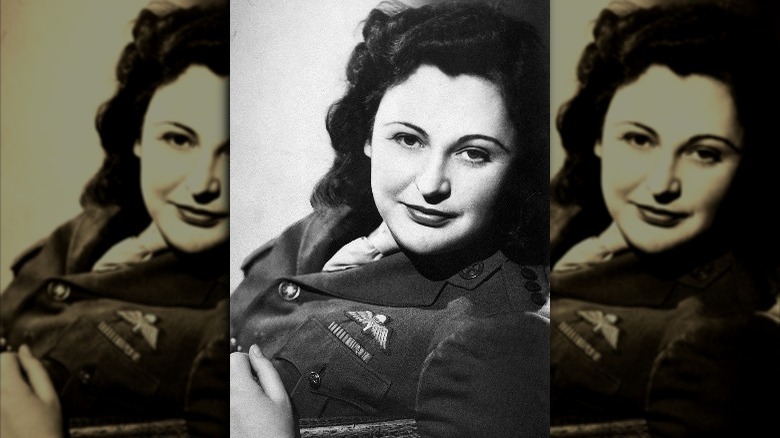

Nancy Wake: the White Mouse

One French Resistance member described the woman nicknamed the White Mouse like this (via The Guardian): "She is the most feminine woman I know until the fighting starts. Then she is like five men."

Credited with needing nothing more than her bare hands to kill an SS guard, Nancy Wake was the one who went on record as saying, "In my opinion, the only good German was a dead German, and the deader, the better." This was from the Australian woman who picked up and moved to London when she was just 16, who had the misfortune to be living in France when it fell to Nazi occupation. She started out carrying messages for the Resistance, but after fleeing to Britain — the Gestapo right on her heels — she returned to train guerilla fighters and head up an arm of the Resistance that ultimately had more than 7,000 members.

Wake's exploits are nothing short of legendary, and the one she dubbed most useful was her 300-mile bicycle ride, undertaken to deliver secret codes. She was also behind the network that smuggled hundreds of Allies out of Nazi territory, arranged weapons drops, trained thousands for D-Day, and made the hard decisions — including interrogating suspected Nazi spies and, in at least one case, sentencing them to execution (via The Washington Post).

In spite of the bounty the Gestapo placed on her head, Wake survived the war. She died in 2011, at 98 years old.

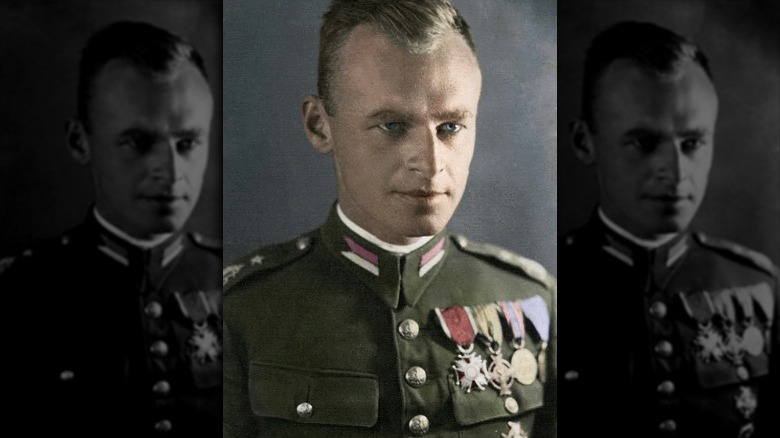

The man who volunteered to go to Auschwitz

Today, we know what was going on in the network of concentration camps set up by the Nazis. But when they invaded Poland in 1939, no one had the foggiest idea what was going on — and in order to find out, one member of the Polish resistance said goodbye to his young wife and his children and then volunteered to head into the very depths of hell on Earth.

That was Witold Pilecki, and according to The Washington Post, he got himself arrested and sent to Auschwitz. Narrowly avoiding being one of the 10 men pulled aside and shot as an example to others, he was told: "The rations have been calculated so that you will only survive six weeks."

Pilecki organized an underground resistance within the camp, and at the same time he was smuggling information out, he was conducting operations to steal food, sabotage the Nazis, and spread what little information he received back into the camp. He and his crew even took out a good number of SS guards, by some creative methods — like collecting typhus-carrying lice and infecting the clothing of the officers (via CBC).

In 1943, Pilecki — now sick and frail — escaped. His messages had made it all the way to Allied command in London, but his story isn't a happy one. Suffering from depression and PTSD, he later fought in support of a free Poland and, in 1947, was arrested and executed as an enemy of communism.

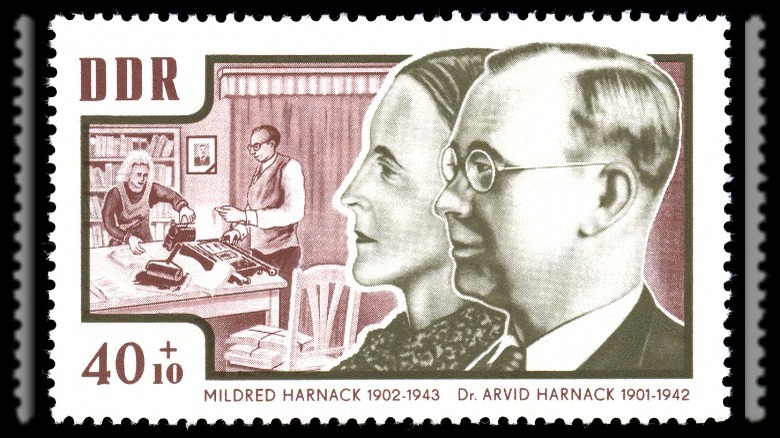

The American civilian executed on Hitler's orders

France and Poland had their underground resistance movements, and according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Soviet Union did, too. The Gestapo dubbed the Soviet spy network the Red Orchestra, and on December 22, 1942, Arvid Harnack was executed in Berlin. He had been caught passing information on German military production to the Soviets, and for his crimes, he was hanged.

There's much more to the story: Harnack's wife, Mildred Fish-Harnack, was a member of the Red Orchestra as well. The two had met in her home state of Wisconsin when they both attended UW-Madison in the 1920s, and after falling in love, they ultimately married and moved to Germany.

As Hitler rose to power, they joined up with a resistance movement, collecting information and sending it on to Moscow. They also met with U.S. officials to help identify German agents on U.S. soil, and their role in the Red Orchestra was discovered in September 1942. A Gestapo raid saw 120 people arrested.

Hitler ordered an example to be made of them. Several months after Arvid was hanged, Mildred was sent to the guillotine on February 16, 1943 (via The New York Times). She became the only American civilian executed by Hitler's direct orders.

The real-life Moneypenny

The New York Times says that even though Ian Fleming never confirmed exactly who was the inspiration for the "James Bond" franchise's Moneypenny, it's pretty clear the answer is Vera Atkins.

Atkins, who died in 2000 at the age of 92, was at the head of the Special Operations Executive spy agency's F division. Those were the units that were sent into France, and Hitler was so fed up with them that he famously promised they were going to be among the first he hanged when he got to London. He, of course, never got there, and Atkins had a lot to do with that. She was in charge of training spies in what might be the most valuable part of being a successful agent: blending in. Not only was she responsible for wartime training, but she also proved a force to be reckoned with post-war.

That's when she took the names of the 117 people who had died at the hands of the Nazis and promised to get them each justice — and she did. According to The Guardian, she spent more than a year traveling Europe and interrogating everyone from concentration camp guards to Rudolf Hess — and those already on the front called her one of the most effective interrogators working for the Allies. Not only was she able to determine exactly what had happened to the missing agents, but when she suggested to Hess that he had overseen 1.5 million deaths, he confessed the actual number: 2,345,000.

Criminals, or resistance fighters?

Usually, history tends to remember those who protested against the Nazi regime as the good guys, but here's the weird thing: The group that branded themselves the Edelweiss Pirates is still remembered as a loose criminal organization, says DW.

And that's strange. Historians are fighting to turn their legacy from petty thieves into resistance fighters, and it's pretty dark stuff. Jean Julich is one of the survivors, and he recounted how his father had been beaten and dragged from his home alongside his mother and aunt, and how he had been sent to an orphanage. Later told he needed to join the Hitler Youth, the memory was still fresh for Julich.

So, he joined a less formal group called the Edelweiss Pirates, and at their peak, there were about 3,000 in their home city of Cologne. While they started out singing songs and pulling pranks, it escalated along with the war. Soon, they were smashing the windows of factories, destroying Nazi transportation, and even derailing trains.

Clearly, the Nazis were not cool with this. Heroes of the Resistance says they were condemned as "riff raff" that threatened the Nazi foundations of the German youth, and on November 10, 1944, they made a show of hanging 13 Edelweiss Pirates, including Julich's friend, 16-year-old Bartholomaeus Schink.

The work of a pacifist

Gertrud Luckner grew up in Germany, and Gedenkstatte Deutscher Widerstand describes her as a "confirmed pacifist." She went on to prove that you don't have to pick up a sword or a gun to make a difference, and she made her mark by organizing the Office for Religious War Relief, with the help — and protection of — Freiburg's archbishop.

Luckner set up a series of international contacts which she then used to oversee a network of people dedicated to helping Jews escape occupied territories before they could be arrested. Most were helped across the borders into Switzerland, and she also oversaw the funneling of food, clothing, and other essential items into concentration camps.

Yad Vashem says that she spent much of her time working alongside the leader of the Reich Union of the Jews, and it wasn't long after his arrest that she, too, was arrested. She spent 19 months in Ravensbrück — until liberation — and after the war, she dedicated the rest of her life to forging connections between the Christian and Jewish communities.