12 Fascinating Facts About The Tomb Of Tutankhamun

Think you know everything about King Tut? Think again. Sure, his tomb met the modern age in 1922 when archaeologist Howard Carter and his team breached its doorway for the first time in centuries. The explosion of interest in Tut and his times that followed came to be known as "Tutmania" and brought Carter to the unexpected level of international celebrity (via BBC).

We also know a fair amount about Tutankhamun and his family, thanks to the ancient Egyptian penchant for making monuments and burying their mummified dead in grand tombs (for the royals, anyway). Per History, Tutankhamun ruled for a decade and died at the young age of 19 around 1324 B.C. Most archaeologists and historians agree that he was the son of Akhenaten, a religious rebel pharaoh who championed the worship of only one god. Because the Egyptian royals were especially concerned with keeping power and riches in the family, Tut was the product of inbreeding and may have suffered health problems as a result. After his death, Tut's remains were mummified and placed in a small tomb in the Valley of the Kings necropolis near the city of Thebes. Close as the quarters were, the space was packed to the gills with riches.

Yet, for all that, there is still much to learn about Tut and how he was buried. What does his surprisingly small tomb have to say about this young king and his turbulent kingdom?

Strange pots heralded the tomb's discovery

When it came to royal mummies, it wasn't just gold, jewels, and other riches that were entombed along with the deceased. Just about anything involved in the embalming process had to be properly buried as well, according to Smithsonian Magazine. That included spare bits of linen wrappings, natron salt used to dry out the corpse, and anything used in funeral rituals, like flowers.

Tut's burial ephemera was first excavated in 1907 by Theodore M. Davis, who found about 12 large jars in a small pit close to the burial of Ramesses X. It wasn't obvious that the jars full of broken pottery, natron, and scraps of linen were signs of anything grander, even though the fabric carried the name of an obscure pharaoh known as Tutankhamun. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Davis assumed he'd found the young king's burial. Years later, another excavator, Herbert Winlock, linked the jars' contents to Tut's mummification and funeral.

But while some thought that the jars were all that was left of Tut, Howard Carter took this find as evidence that the pharaoh was buried nearby. When he finally excavated Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922, Carter found fragments of whitewashed jars that could have been part of the same set found by Davis.

Howard Carter wasn't the first to open Tut's tomb

Howard Carter and his associates may have benefited from the story that they were the first humans to lay eyes on Tut's tomb since it was first sealed. It certainly framed them as groundbreaking explorers and made the glittering find all the more special. But, if anyone pushed that tale, it was only a convenient, headline-grabbing story. That's because Carter was hardly the first person to break into the dead king's burial place.

Carter himself didn't shy away from outlining the evidence of tomb robberies. In the careful excavation notes (per Griffith Institute, Oxford University), fellow archaeologist Alfred Lucas noted that robbers likely rifled through boxes and scattered the contents in the tomb. What's more, human-sized holes had been made in the entranceways. The treasure may have been left behind because robbers were working in the poor light of small lamps. They may have also been reluctant to press their luck on a second visit, especially given that someone eventually resealed the doorways.

Tut's tomb was broken into twice in the ancient era, according to the World History Encyclopedia. Ultimately, it was hidden beneath rubble and forgotten. Lord Carnarvon, Carter's expedition funder, suggested (via the Griffith Institute) that a workers' village was built right on top of the tomb because Tut's burial spot had passed completely out of memory.

The tomb may have been meant for someone else

Even though it was packed with riches, Tut's resting place was still awfully small for a pharaoh. According to the Theban Mapping Project, KV62, as Tut's tomb is known, consists of a simple corridor that leads to four small chambers, most of which were left plain. The plan echoes the lower portions of more elaborate tombs.

The small footprint of the tomb has led some to believe that this spot wasn't intended for Tutankhamun in the first place. But if he isn't supposed to be there, then who was? The Theban Mapping Project suggests that Ay, Tut's successor, may have used his own future tomb when the young king died suddenly. And with Tut's mummy squirreled away in Ay's somewhat more humble tomb, a larger one was conveniently available for Ay himself.

Archaeologist Nicholas Reeves is willing to go even further. As he told The Guardian, Reeves thinks the tomb and its contents were really meant for Nefertiti. She was the wife of Tut's father, Akhenaten, and may have ruled in her own right after her husband's death. Could some of the art and treasure have even been meant for her, and then reworked to make do for Tutankhamun's funeral? While Reeves has been a vocal proponent of the idea, others have found his evidence to be circumstantial at best. Saying that the figure of Tut in a tomb painting looks "feminine" is not exactly a smoking gun, after all.

The treasures may have been made for a queen

Tutankhamun's burial mask is so famous that, not only is it indelibly associated with the tomb and the young pharaoh, but it's since come to represent the cultural heritage of Egypt itself. Despite all that, there are some doubts as to whether or not it actually represents Tut himself.

That's the suggestion of Nicholas Reeves, whose 2015 paper in the Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections claims that there's something up with the famous golden mask. Specifically, he argues that an inscription on the mask with Tut's name was actually carved over another one identifying the owner as Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten — perhaps a feminine name. It's also possible that Tut's middle coffin was also intended for a mysterious person Neferneferuaten, as per History Extra.

But who is this shadowy person? The identification of this possible ruler is complicated by the upset that followed Akhenaten's death and the attempted erasure of his legacy by later pharaohs like Horemheb (via World History Encyclopedia). Some suggest the person was a female ruler, perhaps even Nefertiti ruling alone after the death of her husband. It's a tantalizing theory, especially given that the golden mask appears to have been pieced together with Tut's face but with certain traditionally feminine characteristics, like double-pierced ears, as Reeves noted in the Bulletin of the Egyptological Seminar.

It was buried under rubble

After the first two incursions courtesy of ancient robbers, Tutankhamun's tomb lay quiet and forgotten for centuries. That worked out pretty well for Howard Carter, not to mention modern Egypt's culture and its tourist industry. But how did the tomb fade into obscurity?

It's thanks in part to garbage. More specifically, archaeologists have found that rubble from the construction of other tombs nearby found its way into and on top of Tut's tomb entrance, as per National Geographic. Essentially, workers on a hillside above tossed excavated material down, mindless of the royal tomb directly below them. Smithsonian Magazine also notes that dry as the Valley of the Kings may seem today, it's been subject to occasional flooding throughout the centuries. It appears that not only was Tut's burial place covered over by construction materials, but an ancient flood brought in silt and other materials from the nearby Nile.

As a result, the 20th-century Egyptian workers who completed the actual work excavating the tomb undertook some seriously hard labor. They had to move an estimated 150,000 tons of rock that had accumulated over the many generations to get to Tut's resting place (via National Geographic).

Tut wasn't the only occupant

Tutankhamun's mummy spent many centuries in the quiet of the grave, but it was hardly alone. Writing in "The Tomb of Tut Ankh Amen," Howard Carter noted the discovery of two small coffins that each contained the mummified remains of a stillborn infant. According to the American Journal of Roentgenology, it wasn't until the 1930s that a closer medical exam revealed both fetuses were female. Though incautious handling and care over the years have damaged both tiny mummies, modern studies of the two haven't found any evidence of congenital abnormalities. That goes against one of the more popular conceptions of Tut as an inbred royal. However, both historical and DNA evidence make it clear that his family engaged in at least cousin marriages, as per the Harvard Gazette, or even unions between full siblings (via JAMA). This sort of consanguinity would hardly have helped Tut's unborn daughters from a genetic standpoint.

Another even smaller coffin contained a lock of hair. The small braid was oiled and wrapped in linen before it was placed into a tiny replica of a sarcophagus. According to Carter's notes, the inscriptions on the container indicate that the hair belonged to Queen Tiye. Married to Amenhotep III and giving birth to Akhenaten — who would later have a son, Tutankhamun — Tiye was an exceptionally powerful woman who enjoyed widespread acclaim (via World History Encyclopedia).

The tomb contained treasures from the sky

Inside Tut's linen wrappings were many objects, as Howard Carter outlined in his notes taken during the 1925 examination of the mummy. These included amulets, pieces of jewelry, and two daggers. The one made of gold found on Tut's right thigh was certainly fancy, with its crystal cap. But it has been the iron one found higher up on his mummy that's drawn more attention over the years.

Ancient Egypt existed during the Bronze Age before ironworking was developed on a significant scale. As a 2017 study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science made clear, this dagger was made with meteoritic iron. Instead of attempting to refine iron from plain old Earth rocks, ancient metalsmiths found a richer source in meteors that had fallen to earth. The relatively high nickel content of Tutankhamun's iron dagger makes it clear that it originally came from somewhere far beyond our planet.

Extraterrestrial riches also make an appearance in an elaborate pendant found in the tomb. At the center of the piece, surrounded by gold and inlaid bits of precious stones, is a scarab beetle made from an unusual yellow glass. As per Atlas Obscura, this is now known as Libyan Desert Glass, formed when a meteor slammed into the desert east of Egypt about 20 million years ago. The intense heat of the impact (or an explosion just above the sand) melted the quartz sand and formed the glass, known as an impactite.

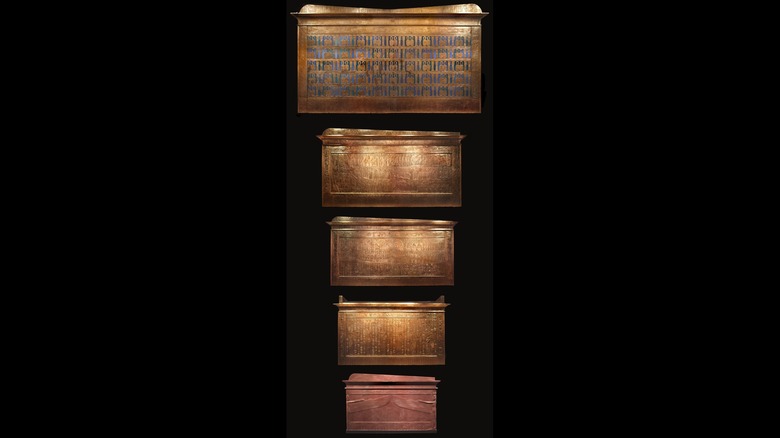

Tut was entombed in many elaborate containers

While most Egyptians would have probably been happy to be entombed within a single, decently-decorated coffin, such plainness was a no-go for a pharaoh. Even Tutankhamun, who seemed destined for obscurity thanks to his short reign and the power grabs that followed his death, was given royal treatment. This meant that, when it came to containers for his mummy, one was hardly sufficient.

According to Howard Carter's notes, Tut was encased in a nested series of shrines and coffins, starting first with a large outer shrine that had been crammed into the tomb. Inside that was a second shrine covered with a fine cloth, which contained two more shrines nested within each other.

Once the excavation team had gotten past the shrines, they were finally met with the first of the anthropoid, or human-shaped, sarcophaguses. The first and largest was made out of quartzite and contained three nested coffins, all richly decorated with gold and depicting Tutankhamun as Osiris, the god of "the underworld." As per Egypt's Ministry of Antiquities, the outer and middle coffins were made of gilded wood inlaid with glass. The third coffin, however, was made of solid gold and weighs more than 240 pounds.

The young king was outfitted with fancy clothing

All of the goods buried alongside Tutankhamun certainly weren't meant to impress anyone living. Instead, as the World History Encyclopedia reports, ancient Egyptians buried their dead with all these objects to keep their loved ones supplied in the afterlife. These included tools, games, food, and miniature shabti dolls that were thought to spring to life and become servants for the deceased in the afterlife.

For Tut, his relaxing afterlife also demanded a full wardrobe. As The New York Times reports, for many years after Howard Carter's excavation, most researchers assumed that the textiles in the tomb were too degraded to be worth studying. But it turned out that researchers were able to catalog much of the pharaoh's clothing, thanks in part to Carter's detailed notes. They found that Tut was buried with 145 loincloths, 28 gloves, four socks, an array of leopard skins, a golden belt, golden sandals, and even a pair of sleeves that may have been used to imitate the wings of the gods themselves.

Many of the clothes appear to have been hurriedly stuffed back into boxes, likely after evidence of tomb robbery had been uncovered (via The Guardian). They also suffered extreme damage while in modern storage, which reduced some textiles to blackened, crumbling messes. Still, researchers have found that Tutankhamun's duds were seriously high quality, with fine fabrics and difficult-to-source dyes meant to further enhance the status of the young king.

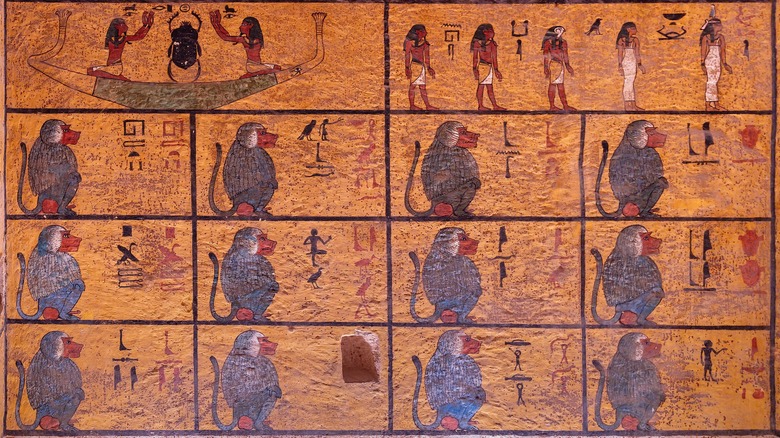

The tomb is full of ancient microbes

Take a close look at images of Tut's tomb today, and you'll likely notice that, on the painted murals is a scattering of odd brown spots. According to an analysis conducted by the Getty Conservation Institute in concert with Egypt's Ministry of Antiquities, the spots were already there when Howard Carter entered the tomb, though no other tomb has been found in the necropolis with similar markings. Some worried that the spots were a sign of fungal growth or some other form of damage inflicted by years of tourists, researchers, and film crews entering the space. The Getty Conservation Institute found that the spots were indeed made by microbes, but the organisms were long-dead. Because the spots are embedded in the paint itself, rather than sitting on the surface, they can't be cleaned off.

That last fact offers a clue into the circumstances of Tut's burial. Microbiologist Ralph Mitchell, of Harvard's School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, suggests that the tomb must have been only half-ready when the young king died. As workers rushed to finish the tomb and pack the grave goods into the small space, they very well could have left wet paint on the walls. It dried out eventually, but not before an unidentified microbe proliferated and left its telltale mark.

Finds from the tomb got botanists and food historians excited

The tricky thing about royal burials in ancient Egypt is that they often only tell us about the richest and most fortunate. Yet, even amongst the riches of a king, some careful research can reveal more about the common people that often get left out of the story.

As the Los Angeles Times reported in 1988, a graduate student's rediscovery of real food and a floral wreath placed in Tutankhamun's tomb proved to be a major development. The goods, which had been lost in storage for decades at Britain's Royal Botanic Gardens, included about 25 plant food species and another 30 types of weeds. The find also included some insect pests, hinting at troubles with crop growth and famine. Researchers also found sections of a funeral wreath made with olive leaves and blue cornflower, which was also recorded in notes made by Howard Carter's research team in the 1930s.

Other foods found within Tut's tomb are likely more indicative of what graced high-class Egyptian tables, and what King Tut may have eaten when he was alive, however. As a 2013 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences made clear, some tombs sported mummified bits of meat, including beef ribs found in the tomb of Tut's great-grandparents. These intentionally mummified vittles could receive nicer treatment than some humans could have hoped for, with linen bandages and fine resin completing the package.

The tomb might be part of a larger complex

Sure, Tutankhamun was ultimately a minor pharaoh who was readily forgotten in the grand sweep of ancient Egyptian history. But even for a royal who was comparatively small peanuts, the small size of his tomb has really bothered some archaeologists. Nicholas Reeves, the archaeologist who may be the most vocal about his desire to excavate more of Tut's tomb, told The Guardian that he believed the tomb originally belonged to Nefertiti. What's more, he said that it's possible there are more chambers beyond what's been excavated. Perhaps one contains the mummy of Nefertiti herself. However, radar surveys have proven inconclusive and no one in Egypt's Ministry of Antiquities has signed off on further excavation.

Fantastical as it sounds, the idea of a sprawling underground tomb complex in the Valley of the Kings isn't far-fetched at all. In 1987, archaeologist Kent Weeks and his team uncovered the entrance of KV5, which had been previously dismissed by other archaeologists (via Theban Mapping Project). Howard Carter himself had directed laborers to dump material from the excavation of Tut's tomb on top. Yet excavators instead found what's now the largest-known tomb in the valley, with at least 120 chambers. It appears to have begun as a small tomb that was enlarged by pharaoh Ramesses II to bury some of his many sons and their grave goods.