The Untold Truth Of Mummies

Mummies have certainly gotten a bum rap over the years. They've been featured as villains in Halloween specials, low-budget horror flicks, and even a few Hollywood blockbusters — like 2017's The Mummy, starring Tom Cruise. But few people know the real truth about mummies and how they've been used throughout history. Some of these facts are far weirder than anything Hollywood has come up with. Here's everything you ever wanted to know about mummies — and plenty more that you didn't.

(This article is about historical mummies, but if you wanted to read about mummies in the movies, we've got you covered at that link.)

Not all Egyptians were mummified

Mummification wasn't a rite of passage that every Egyptian had the honor of experiencing. It was actually an expensive process that not everyone could afford. So, just like your gym membership or cell phone plan, the Egyptians offered the families of the deceased three different mummification package plans, and, of course, the most expensive plan was the only one worth getting.

The highest level of mummification involved thorough cleaning of the body, delicate removal (and cleaning) of its internal organs, and infusing it with valuable substances, like "pure myrrh" and cassia. The other options were far more careless with the body by comparison. But while the other two options were cheaper, they carried a higher social cost. Families that selected those options, especially if it was public knowledge that they could afford a better plan, put the family at risk for social shame. But wait, it gets worse: it was also said that those families who cheaped out in regards to the embalming of a family member would risk being haunted by the deceased.

Really, if your option is paying more for a better mummy or being cursed forever by your dead uncle, the choice seems like no choice at all.

Corpse "slitters" had a thankless job

The Egyptians held the human body in such high regard that it caused some moral conflict during the mummification process. Crossing over to the other other side required having a whole, unharmed body, so causing harm to a person — even after they were dead — was strictly forbidden. That, of course, made the embalming process kind of difficult.

Mummification involved removing cutting a corpse open and removing all their organs, so the Egyptians had to get a little creative so they could get around their restrictive laws. This led to the creation of the slitter, who had two jobs: 1) cut open the body, and 2) run.

Why'd they have to run? Well, after making the incision in the corpse, slitters had to run from the rock-throwing mobs who were ceremoniously sent after them as punishment for harming dead bodies. So in addition to being good with a knife, slitters needed to have a decent set of legs, too.

Open-mouthed mummies

The Egyptians' mummification process also included a ritual known literally as "opening of the mouth," which is pretty much exactly what it sounds like. Either the corpses' mouths or the mouths on their face masks were left open to symbolize the act of breathing. Because the Egyptians believed that life continued after death, the idea here was that the ritual could rejuvenate the person's senses. It didn't, of course, but that didn't stop them from doing it.

The open-mouthed mummies were also supposedly able to enjoy the food and drinks that loved ones offered during tomb-visits. The best part of family picnics in the pyramid after you were dead? Calories were no longer an issue.

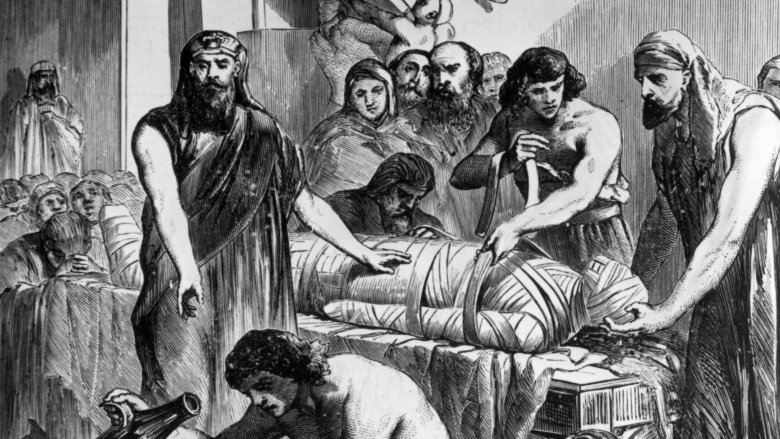

Unwrapping mummies was a popular attraction

As we've clearly established, much of ancient Egyptian culture revolved around life after death and preserving the body for the afterlife. So why not completely disregard their beliefs and turn their corpses into a public spectacle? That's what the British did. During the Victorian age, mummies were unwrapped on stage in academic settings, usually with the intention of learning more about ancient Egypt. However, these exhibitions fascinated the public, and they were often attended by plenty of people who weren't actively involved in Egyptian scholarship of any kind.

Thomas Pettigrew, a well known surgeon, was most known for hosting these events, which he called "unrollings," where he unwrapped mummies and performed autopsies for enormous audiences. Thankfully the appeal of these kinds of events eventually wore off in the early 1900's.

As weird as that sounds, it's nothing compared to what was done to the bodies after the unwrappings were over...

Mummies were ground up to make paint

After mummies were purchased, unwrapped, and ultimately worthless when these unwrapping events came to an end, the bodies were often sold to manufacturers. Now, what could manufacturers do with a bunch of dried up, unwrapped mummy corpses? The answer is so grotesque, it's amazing that it was able to continue for so many years. After they were purchased, these mummy remains would be ground up and used to create a paint pigment literally called Mummy Brown.

According to an article published by Scientific American, artists would use the paint in their art without actually understanding the source of the color, said to be "a highly variable pigment between raw umber [...] and burnt umber." So some of those older paintings you might have hanging around your house may have been created using parts of a dead body, such as Martin Drolling's 1815 painting Interior of a kitchen, pictured above.

The article explains that, because it was a "figurative" color, Mummy Brown "faded easily." The result was diminished interest in the paint from artists. But that didn't stop paint manufacturers from still making the stuff. It wasn't until the 1960s that paint companies stopped producing Mummy Brown...because they ran out of corpses.

That's right, Mummy Brown wasn't discontinued because it's disgusting, disrespectful, or just outright wrong. It's because they were fresh out of mummies.

Mummy medicine

If you thought the weirdest uses for ancient Egyptian corpses was publicly desecrating them or grinding them up for paint, you'd be wrong. That's because back in the 17th century, mummies were also ground up to create the Baroque period's equivalent to Tylenol, thought to cure practically anything from everyday headaches to internal bleeding.

The mummy's skull was an especially valuable part of the corpse, as the moss that sometimes grew on it after burial was thought to have impeccable healing qualities. That moss would be ground up and ingested to get rid of nosebleeds and symptoms associated with epilepsy — neither of which are life or death situations that might justify eating the gunk that grows on a dead man's skull.

But that's not all. These corpses' supposed healing powers went beyond the realm of the physical, and entered into that of the spiritual. According to Clive Gifford's book Killer History, a substance called "Mummy Powder" or "Mummy Dust" was in high demand among the wealthy since the 12th century. In fact, England's King Charles II believed the small mummy particles in Mummy Powder contained the secret to greatness. He "often rubbed the powder on to his skin so he could absorb the ancient greatness of the pharaohs." Meanwhile, a few hundred years earlier, France's King Francis I drank a mix of dried rhubarb and mummy powder every day — because he "thought it kept him strong and safe from assassins." Sounds healthy.

Some mummies were accidents

Not all mummies had the luxury of having their organs professionally removed and their mouths gently left agape. Some, in fact, became mummies purely by accident. These poor, unglamorous corpses are called bog bodies.

Found throughout Europe, bog bodies are the naturally mummified results of people dying amid bogs and wetlands. These oxygen-poor areas are rich in anti-microbial peat moss, so the bog bodies discovered within are often incredibly well-preserved. An article published by the History Channel says that bodies hundreds of years old still have "discernible facial features, fingerprints, hair, nails and other identifying traits."

Frankenmummies

The Egyptians may have been the most famous culture that practiced mummification, but they weren't the only ones. In fact, in 2001, scientists discovered several 3,000 year old mummies on an island near Scotland — but that's not the weirdest part. No, the strangest aspect of these Scottish mummies was the fact that, according to National Geographic, these mummies actually contained the parts of several different bodies. Apparently these "Frankenstein mummies" were originally mummified in a bog, before being re-buried 300 to 600 years later.

Researchers have several opinions on what exactly occurred here. One theory is that when the bodies were discovered a few hundred years after their deaths, they were buried properly. The people doing the burying simply combined the parts of different corpses they found to make complete bodies.

A more far-fetched theory is that these Frankenstein mummies were created intentionally, choosing one piece from several bodies that portrayed a specific trait from the family lineage until a complete body was formed. That's a pretty sick idea for a family tree.

Some Japanese monks mummified themselves...while still living

You might think the mummification process begins only after a person's last heartbeat. But according to Atlas Obscura, a small number of Shingon monks in Japan began to mummify themselves while they were still breathing. The goal of the practice was to enter a state of deep, eternal meditation, and over the course of about 800 years, over a dozen monks actually succeeded at making mummies of themselves.

It began with a pretty nasty diet that forbade the ingestion of anything but what could be found in the wooded mountains where they lived in solitude, leaving them to eat nuts, roots from trees, bark, and pine needles. Thought to cleanse the spirit, this strict diet also eliminated body fat, muscle tissue, and moisture — ultimately beginning mummifying the body while they were still alive.

This was done for 1,000 days, alternating between foraging for food and meditating until the cycle was considered to be complete. Most of these Japanese monks went through the cycle several times before feeling that they were truly ready for the final step...likely because the final step was death. They'd stop eating until they felt that it was finally time to die. At that point they'd call on their friends to bury them into a relatively small pit with just a small tube leading to the surface for air so they wouldn't suffocate, but instead would die from starvation.

The process was far from over, however. A thousand years after their burial, the tombs of these monks were opened to see if mummification was successful. Only the bodies that showed no sign of decay were considered successful and were enshrined. All the others were discarded and basically considered a giant waste of time.