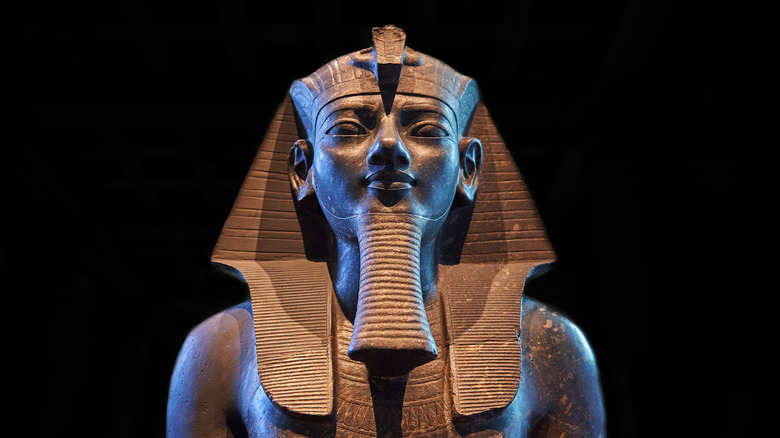

The Untold Truth Of King Tut's Grandfather Amenhotep III

The Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun is as famous as he was unaccomplished. The "boy king," as he is called, died at age 19. According to an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association, he was a sickly inbred who could barely walk without a cane. But the boy king's ancestors were at the forefront of Egyptian history.

His father Akhenaten sent the country into flux after he completely upended Egyptian religion at his capital of Amarna. Most of the glory, however, went to Tutankhamun's grandfather Amenhotep III. This Egyptian pharaoh reigned nearly 40 years and boasted an impressive array of monumental and diplomatic achievements that saw Egypt reach an unparalleled level of prosperity in the Bronze Age Near East. While Amenhotep's major achievements are well-cataloged, of greater interest are the lesser known details of his reign, which have led to decipherment of languages, provided information on the Trojan War, and much more. Here is the untold truth of Amenhotep III.

He lived to celebrate 30 years

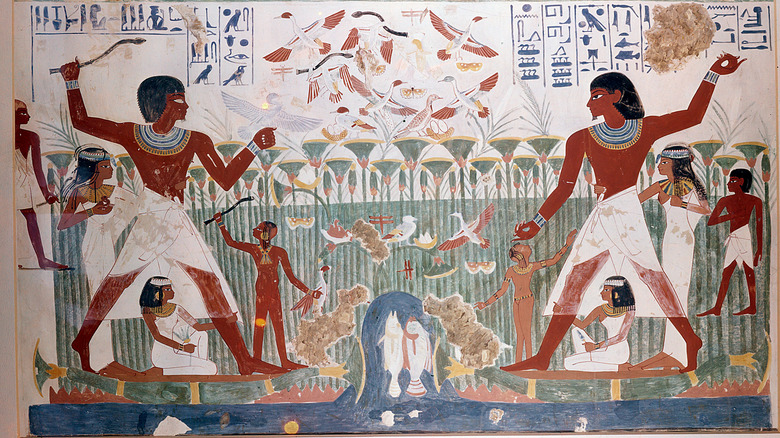

Egyptian religious tradition allowed any pharaoh that reigned 30 years to celebrate the Sed Jubilee Festival. As Egyptologist Lawrence Berman (via "Amenhotep III Perspectives on His Reign") notes, most pharaohs probably did not make it to that milestone and had to content themselves with "millions of jubilees" in the afterlife. But Amenhotep celebrated three jubilees, as was his right after reigning nearly 40 years.

According to University College London, the Sed Festival was supposed to renew the king's spiritual and physical energies as he aged. Little is known about the exact order of the festival celebrations: It must be reconstructed from numerous texts and illustrations. Much of the evidence comes from Amenhotep himself, who delved into past Sed festivals to throw a party that the world had not seen for centuries.

The records suggest a lavish celebration. Finds of meat, wine, and ale from Amenhotep's Malqata Palace suggest that the pharaoh provided revelers with plenty of food and alcohol while his officials received gifts of gold jewelry. Artisans produced hundreds of life-sized statues of the king across Egypt to commemorate his reign. Altogether, this celebration was very expensive and, apparently, exclusive. The king of Babylon, Kadashman-Enlil I, complained in Amarna Letter 3 (via William Moran's "The Amarna Letters,") that he had neither been invited nor sent a gift in commemoration of the celebration. If a fellow king was upset at the snub, it must have been some party.

He deified himself

While all Egyptian pharaohs generally were considered demigods, Amenhotep III took the symbolism to a new level following his 30-year jubilee celebrations. According to University of Chicago Egyptologist W. Raymond Johnson, there is a change in royal iconography around year 30 of his reign. Despite being a man in his 40s with a myriad of health problems, Amenhotep began depicting himself as a younger and younger man, and eventually as a child. Amenhotep's temples were even decorated with scenes of the pharaoh worshiping himself. The iconography's symbolism conveyed the pharaoh's unity with the sun god after his 30-year jubilee. This was not normal in Egypt. Normally, the unity between the sun god and the king occurred after the king was dead, as seen in the Pyramid Text of the Old Kingdom, which predated Amenhotep III by at least a millennium.

The deification of the living king had enormous repercussions for Egyptian religion. By declaring himself the sun god, Amenhotep had effectively declared himself the living manifestation of all Egyptian gods, who sprung from the seed of the sun god Atum-Re. Thus, Queen Tiye was represented as the consort of the sun god, Hathor. Akhenaten, his successor, was depicted as Shu, the offspring of Re, while his wife Nefertiti was Tefnut, Shu's sister-wife. This is likely the origin of the Aten cult (explained in "Akhenaten and the Religion of Light") that took hold in Amarna years later under Akhenaten.

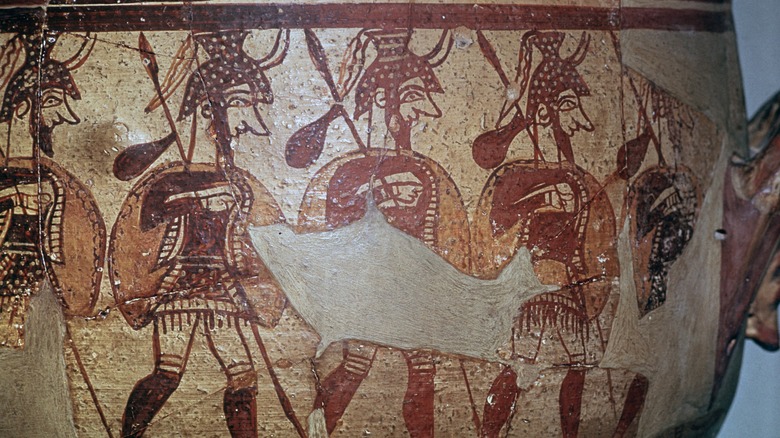

He maintained relations with Homeric Greece

The Amarna Period, as the Late Bronze Age is often referred to, was a time of far-flung international relations between the powers of the day. Among Egypt's diplomatic relations were the states of Bronze Age Greece, most famous thanks to Homer's epic poem the "Iliad."

Writing in the Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections, professors Eric Cline and Steven Stannish identify a handful of place-names in Greece that were carved onto Amenhotep III's famous Kom el-Hetan stela. The two most important that have been definitely identified are Mycenae, home of Homeric hero Agamemnon, and Knossos, home of King Minos, the Labyrinth, and the Minotaur. A further two are unclear, but one might refer to Boeotian Thebes in Greece, while the authors reject the second's identification with Troy itself. The rest are a series of lesser Greek and Cretan toponyms.

The Kom el-Hettan stela shows that the states of Bronze Age Greece and the Aegean were not outliers on the edge of civilization. Rather, they were important political entities that participated fully in the diplomacy of the Late Bronze Age, and the stela might be the record of a diplomatic trip. This squares with archeological evidence. According to Jorrit Kelder, Mycenae was known as "rich in gold" and as a center for gold and silver artisanry. The rulers that built the citadel's impressive walls (via Brown University) were certainly not poor, insignificant warlords. WIth such power, it is certainly possible that a Mycenaean expedition of "a thousand ships" could have burned Troy.

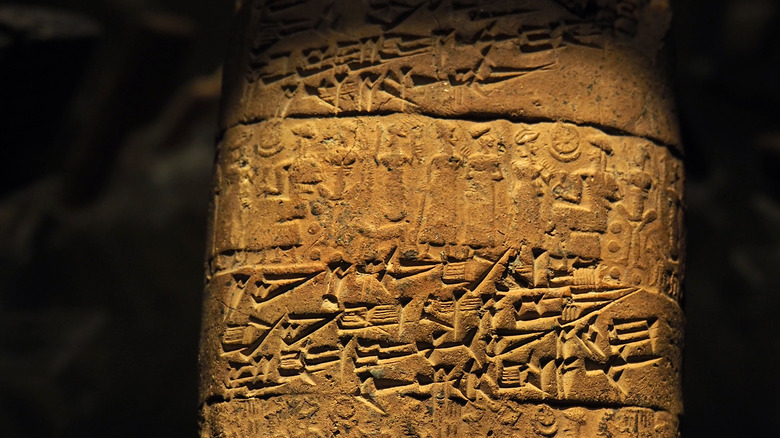

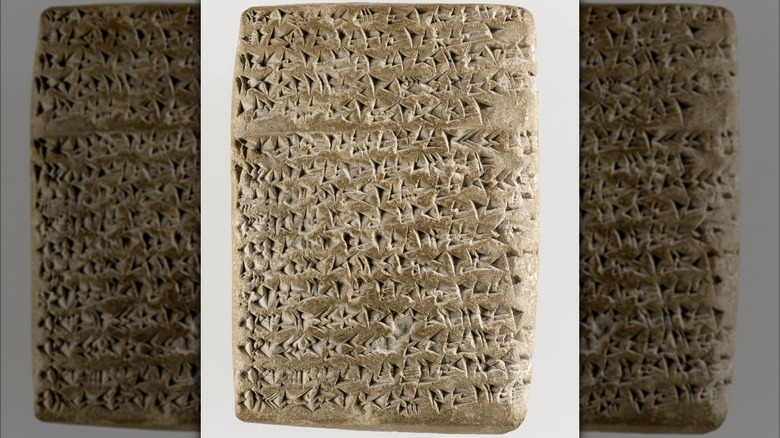

His letter allowed the decipherment of Hittite

Among the letters found in the Amarna Archive were two written between Amenhotep III and Tarhundaradu, the ruler of a western Anatolian state called Arzawa. These two letters became the basis for the decipherment of a then-unknown language called Hittite, which would change the field of Indo-European linguistics.

According to University of Michigan professor Gary Beckman, Danish philologist Jorgen Knudtzon tried to decipher this mysterious language of the Arzawa letters. Fortunately, the cuneiform script in which they were written was already deciphered, so the letters could at least be read. It was unknown, though, what kind of language the symbols wrote. Knudtzon, however, found the words "estu," "-ti," and "-mi," which resembled the Indo-European words for "let it be," "to you," and "to me" respectively. Thus, he assumed that the language in question was Indo-European, a very distant relative of English. His conclusion, however, set off a firestorm of controversy. Any language that was located in Turkey must have been a Semitic language related to Akkadian, Hebrew, and Arabic.

While the Danish attempt at decipherment failed, mostly because the Hittite in the text was incorrectly written, their hunch that they were dealing with an Indo-European language was correct. In 1915, Czech philologist Bedrich Hrozny isolated the Hittite word for "water," which incredibly, turned out to be "wa-a-tar." Knudtzon was redeemed. This "Arzawan language" turned out to be the Indo-European Hittite language, the family's oldest attested member.

He was acquainted with YHWH

It was common for Egyptian pharaohs to inscribe their temples with scenes and records of their subjects. One inscription, as transcribed in the journal "Dotawo" reads "the land of the Shasu of yhwa." According to author and archeologist Titus Kennedy, the name is Semitic and appears alongside a host of other Semitic deities from the Levant. Thus, "yhwa" is very likely YHWH of the Bible, the God of Israel whom Jews and Christians worship today.

The evidence for identification with YHWH is strong. Although the temple is in Sudan, Kennedy notes that other Egyptian inscriptions place the Shasu in the Sinai Peninsula and the ancient regions of Moab and Edom (modern Israel and Jordan). According to professor Martin Leuenberger (via ASOR), this squares with YHWH's geographic origins. Biblicists and Near Eastern scholars generally trace YHWH's origins to the mountainous Sinai Peninsula and Red Sea littoral. The Shasu, a catch-all term for these desert-dwellers, spread His cult throughout the Near East, perhaps even into Egypt if one accept Exodus.

The inscription confirms that there were Semitic-speaking peoples under Egyptian rule that worshiped YHWH in the 14th century B.C. of whom the Egyptians were aware. While more research is needed to confirm or deny Exodus, it is undeniable that much of the narrative's historical context is firmly grounded in Amenhotep III's Egypt.

He was a chauvinist of sorts

The Amarna diplomacy involved marital exchanges of royal women to seal political alliances. According to Egyptologist Alan Schulman (via Harvard University), Amenhotep III mastered this system. The Egyptian pharaoh married the daughter of Babylonian king Kurigalzu I along with two princesses of the Mitanni Kingdom. Now according to professor Kevin Avruch, Amarna diplomacy was based on reciprocity. Rulers were expected, in theory, to offer their daughters or sisters to their fellow rulers. But Amenhotep did not.

Although Amenhotep had married Kadashman-Enlil's sister, he did not reciprocate. In EA 4 (via "The Amarna Letters"), Kadashman-Enlil demanded to know why Amenhotep had refused him his daughter in marriage. Amenhotep responded that "no daughter of the king of Egy[pt] is given to anyone." The pharaoh refused to send even a royal woman of lesser status as a wife, to which the Babylonian king threatened to withhold any future royal marriages from his line.

The exchange between the two rulers suggests that Amenhotep viewed himself and Egypt as a cut above the other kingdoms of the Near East. According to Sakkie Cornelius' article published in Scriptura, Egypt viewed itself as the center of the world, while the "vile foreigners," who were stereotyped in three principal caricatures, were on the fringes. While Cornelius notes that mixed marriages among commoners did happen, royal women appear to have been the exception. Thus, an Egyptian princess, the daughter of a literal god on earth, it seems could not lower herself to marry a foreigner.

He was unrelated to his queen

Amenhotep took many wives. There was usually, however, a chief wife who served as queen. Sometimes, the chief wife was a sibling or half-sibling, according to professor Russell Middleton of Florida State. But Amenhotep's wife Tiye was not a sibling, half-sibling, or even, it appears, of royal blood.

In an article published in the journal RCC Perspectives, Egyptologist Barry Kemp and geneticist Albert Zink reconstructed the family tree of King Tutankhamun, Amenhotep III's grandson. From the tree, it was revealed that Tutankhamun was indeed Amenhotep's grandson and the son of Amenhotep IV (aka Akhenaten). However, it also established the parentage of Queen Tiye, the aristocratic daughter of a couple named Yuya and Thuya.

Tiye came from a family of soldiers. Her father had been a chariot soldier and commander who, according to Egyptologist Cyril Aldred, also held a battery of administrative and honorary titles at court and in Egypt's temples. So despite being a non-royal, Tiye was certainly a high-class woman, and from her own correspondence, a very intelligent one. She corresponded personally with at least one foreign ruler, Tusratta of Mitanni. According to Amarna Letter 26 (via "The Amarna Letters"), Tusratta wrote to Tiye to use her influence with her son Akhenaten in pursuit of maintaining good relations with Mitanni. This letter suggests that the queen wielded such an influence over her husband and son that even foreign rulers sought to ingratiate themselves with her.

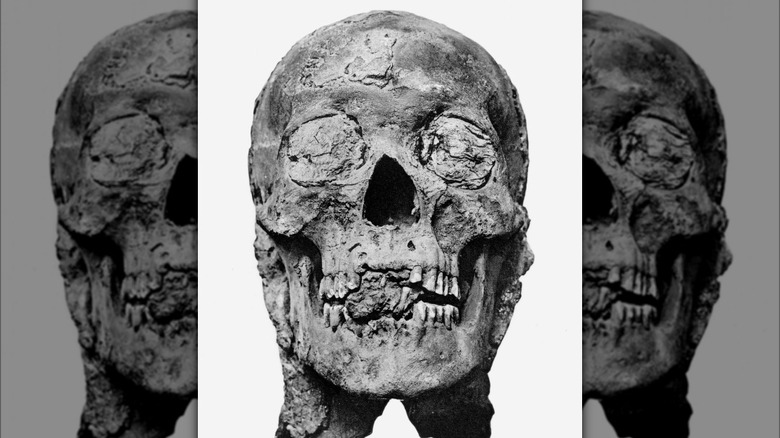

He had terrible teeth

Being a god on earth was no protection from oral problems for Egypt's pharaohs, several of whom suffered from terrible teeth. According to R.J. Forshaw of the University of Manchester, Amenhotep III suffered from periodontal disease (severe infection of the gums), multiple tooth abscesses (a bacterial infection in the tooth with pus buildup), and dental wear from age and use.

Forshaw traces the dental issues principally to the wearing of teeth. Cavities were less of a problem, since the Egyptian diet lacked processed sugar, but tooth wearing was a major medical complaint among all classes. Desert winds tended to blow sand into foodstuffs such as flour, which was then used to make bread. This would not have been a problem if it only happened occasionally, but repeated wearing of the teeth against quartz and other inorganic matter gradually wore away the protective enamel, exposing the teeth roots to infection.

Despite being a pharaoh, it does not appear that Amenhotep III ever received any effective treatment for his problems. Egyptian medical treatments for oral complaints were directed towards addressing symptoms, since the role of bacteria and plaque were unknown. Thus, teeth and gums might be covered with anti-inflammatory and antiseptic substances to slow the infection and provide relief. But ultimately, it was likely that Amenhotep III ended his days in pain as a result of his conditions, which could not at the time be cured.

Thutmose IV was not his father (sort of)

This one is a matter of ideology and Egyptian belief, not biological reality. Although Thutmose IV probably was Amenhotep III's biological father, royal ideology had an alternative explanation. Amenhotep III depicted himself as the literal child of his mother and the god Amun. This idea, according to Egyptologist Uros Matic, was called the divine birth, and provides an interesting glimpse into the Egyptian view of sex between divinities and humans.

The text of the divine birth (reproduced in Matic's article) originally belonged to Egypt's female pharaoh Hatshepsut. Amenhotep III probably copied it. The text narrates that the queen-mother was visited by both the god Amun, who took the form of her husband. Seeing her husband, but realizing it was actually a god, the queen had intercourse with him upon seeing his "nfr.w," which Matic argues is Amun's phallus. The union resulted in a pregnancy with a half-divine child, who would become Amenhotep III.

Amenhotep's reasoning for depicting the divine birth probably related to concerns of legitimacy, as Egyptologist Lawrence Berman explains in "Amenhotep: Perspectives on His Reign." The pharaoh's mother was a minor wife of his father Thutmose IV named Mutemwiya. Since she was not the "Great Royal Wife" (aka chief wife), it is possible that Amenhotep III elevated her status (and thereby his own), by declaring that the god Amun had predestined her to bear the divine child that would rule over Egypt. Thus, the pharaoh legitimized himself, his mother, and linked himself closely to the god Amun through blood ties.

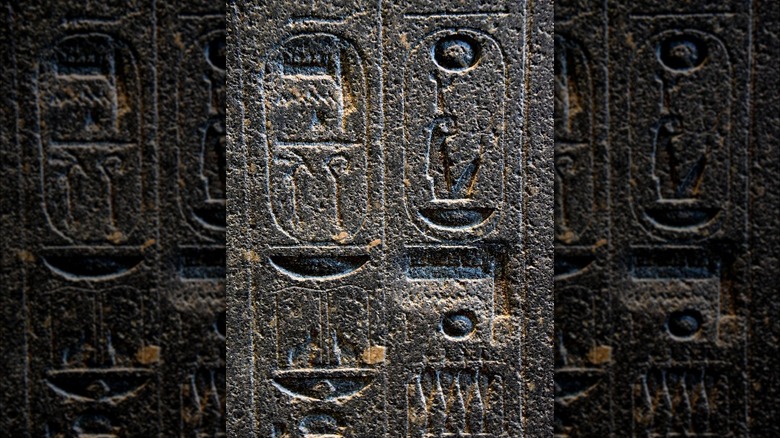

He had five names

According to the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, Egyptian pharaohs had a whopping five names, each related to a title that expounded upon a particular facet of Egyptian royal ideology. The king usually was known by two of these, his birth name, preceded with the Egyptian title "son of Re," and his coronation name, which was preceded with the title "King of Upper and Lower Egypt." The "Two Ladies" name emphasized the pharaoh's rule over both Upper and Lower Egypt in relation to their respective goddesses (aka "the Two Ladies"). The Horus name emphasized that god's role as the royal patron, while the Horus triumphant name (or "Golden Horus") name appears to emphasize the pharaoh's triumph over his enemies.

So Amenhotep's full name, according to University College London would have been Amenhotep Nebmaatre Aakhepesh-husetiu Semenhepusegerehtawy Kanakht Khaemmaat. Quite a mouthful, but fortunately, it was only used in its fullness on official monuments and certain documents. When it came to dealing with foreign rulers, the Amarna Letters suggest that the king simply used his coronation name. So in EA 31 (via "The Amarna Letters"), King Tarhundaradu of Arzawa simply addresses Amenhotep as Nimuwareya, a contemporary vocalization of Nebmaatre, whose pronunciation had undoubtedly evolved by Amenhotep's time.

His military activity was limited

Egypt's 18th Dynasty, to which Amenhotep III belonged, was a military one. It had been forged in war, and throughout its existence, according to Egyptologist Alan Schulman, the military had gained increasing power and influence within the royal court. But strangely, a pharaoh such as Amenhotep did not take part in much military activity, preferring to let his generals do the dirty work on the field. This contrasted with his ancestor Thutmose III (via "The Wars In Syria And Palestine Of Thutmose III"), who campaigned extensively in the Levant, as recorded in his famous "Day Book."

Amenhotep only seems to have participated in a single military campaign in the region of Kush (aka Nubia) south of Egypt. According to Egyptologist David O'Connor (via "Amenhotep III Perspectives on his Reign"), this campaign's objective was to quash a rebellion by a local Nubian ruler named Ta-Zety and ensure that Nubia's gold mines remained in Egyptian hands. It is unclear how large or important this expedition was. Amenhotep claimed to have captured tens of thousands of prisoners, but the stelae commemorating the event is very general and hyperbolic. Thus, it is difficult to situate the exact location of the campaign or the fighting or attest to the true scale of the war. It may have been a small-scale operation that the pharaoh exaggerated, or it really could have been a large-scale revolt. But as O'Connor notes, it is impossible to be certain with current evidence.

He was a prolific hunter

Although Amenhotep III was not much of a soldier, especially compared to his ancestors, he proved his martial qualities through the time-tested means of hunting large game. Anthropologist Laura Betzig (via Journal of Cross-Cultural Research) writes that this dangerous pastime was often used to train princes for war, giving them a chance to practice their weapons skills while also showing off their prowess and courage in the face of wild beasts such as lions.

Amenhotep was a prolific hunter by the standards of the time. According to Egyptologist Lawrence Berman, engraved scarabs attest that the king went on hunting expeditions with his soldiers. But the hunting was not done in the open. Instead, the animals, whether bulls, elephants, or lions, were confined to a large pen, where the king could hunt them at pleasure from his chariot while his retinue watched and admired his skill. In this sense, Amenhotep was continuing a tradition Egyptologists refer to as the "sporting-king" tradition, in which pharaohs showed their prowess on the hunt instead of on the battlefield. Overall, Amenhotep killed at least 100 lions in his lifetime.

While hunting today is mostly for food, Amenhotep had ideological reasons for his love of the chase. According to the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, the Egyptians believed that it was the king's job to maintain cosmic order (maat), to counterbalance chaos (isfet) and keep the kingdom stable. Hunting was a means to this end, since it represented the triumph of the forces of maat (aka Egypt) over the wild, untamed forces of chaos.